Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Jordan Mechner talks about Digital Eclipse's latest retrospective, and how its exhaustive treatment tells the human story beyond the source code.

Gaming history has its share of stories where parents get in the way. Where computers, arcades, and consoles are misunderstood by an out-of-touch generation, and where passionate young designers and coders get into the hobby–and even become famous–in spite of their parents' wishes.

Jordan Mechner had a much different version of this gaming origin story, in that his family was central and essential. This week, the creator of the original Prince of Persia series takes fans into one of the most intimate historical documents of a video game ever made. The Making of Karateka is less of a game and more of an interactive museum exhibit, and it’s special for many reasons—most of all because of how prominently his father figures into it.

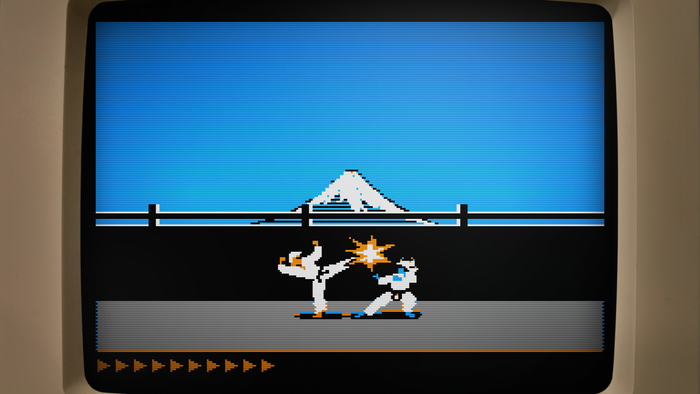

There's a lot to say about both Karateka—a landmark 1984 game for Apple II, Mechner's debut retail game that launched when he was only 20 years old—and this week’s new retrospective release. The Making of Karateka, out this week from Digital Eclipse on all major consoles and PC, is a testament to how the game was made and why it matters so many years later. Its content is exhaustive and then some: Playable prototypes, playable pre-Karateka experiments, modern interviews, and an astounding pile of written, typed, drawn, and filmed documents from the game's development process.

The thing that gets Mechner choked up while calling to talk about the new retrospective from his home office in France isn't the wealth of documentation. Rather, it’s his father’s place in Karateka's story.

"I really feel fortunate to have been able to do that together," Mechner says about his working relationship with his father. “In that way then, and also, you know... to have the chance to revisit it now. That Digital Eclipse has given us this occasion to revisit that, to look at it together. And that my dad, at 92, can look at Making of Karateka, and appreciate that. And he can also see that his work is remembered and appreciated. Yeah, you know, that's... I'm very happy about that. Yeah, that touches me."

Without the context of the new retrospective, you might argue that Mechner's father played a small role in the impact that Karateka had on gaming. But Digital Eclipse’s new Gold Master retrospective series, teased last year by a similar approach in Atari 50, is about more than jumping into and out of old games. The series' curated timelines lead enthusiasts and novices alike through how a game was made, with context supporting each playable slice along the way. In this approach, we see and hear father Francis Mechner’s influence across the game land subtly yet indelibly—like a perfect musical note.

Which, for the man who composed all of Karateka's ahead-of-their-time musical cues, is perfect.

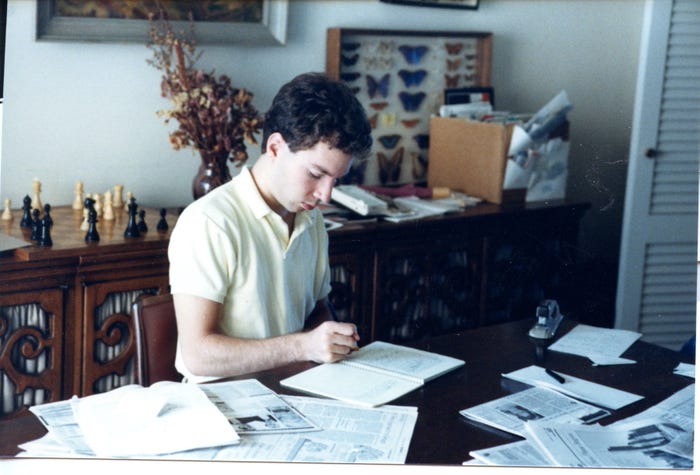

Mechner is careful to remind anyone coming into The Making of Karateka that any stories about his work as a "sole" creator miss the mark. This includes the official support and pushback given by the staff at publishers Broderbund (which you can read at length inside this retrospective), but Mechner also points to the collective he leaned on as a teenager: friends, family members, classmates, and roommates.

"Programming is a lot like writing or drawing a comic book,” Mechner says. "It really helps to show people the work in progress and get their feedback based on who they were." His gaming peers were more likely to compare his incomplete prototypes to other Apple II fare: they knew the platform’s limitations, but they also had expectations for games, as compared to what they'd played and liked elsewhere. That wasn't the case for his non-gaming father.

"With my dad, it was different—and valuable in a different way," Mechner says. "My dad understood Karateka as an artwork. Even though he doesn't play games, he could see what it was, and I could tell him things about how it worked." It’s here that Mechner’s father reflected on the game’s storytelling strokes: a single karate expert (aka a “karateka”) had to beat up every guard inside a stronghold until felling its leader and rescuing a captured princess. Father asked son: can we add music? And can we do it in a way that video games had never done, via leitmotifs–the character-specific musical interludes made famous in the elder Mechner’s favorite operas?

“That's not something any of my programmer friends would have thought of," Mechner says. "But my dad and I, we’d been to Wagner operas together, and I'd seen Star Wars and Raiders of the Lost Ark—so, we talked about how John Williams used the same leitmotif approach." Mechner knew the ask was a lot for the wimpy Apple II: when sound played, all animations had to freeze, and the hardware wasn't even able to play chords.

Music was a tall ask to implement between ambitious art design and a demanding punch-and-kick battle system, but the shared family language and interest was enough to spur the game’s now-legendary music into motion. "I mean, I wanted it!" Mechner says. "My father was offering something that got me excited and that I thought would enhance the game." With that, his father applied his classically trained musical chops and composed a series of leitmotifs, one for each major character, with unusual and tense note fall-offs that were miles ahead of anything else blaring out of arcade cabinets' speakers in the early ‘80s.

Longtime game music composer and journalist analyst Kirk Hamilton guests inside Making of Karateka with a verbose breakdown of exactly why the music is so special. Alternatively, the Mechner father-and-son duo offer a more emotional musical overview in a video where they sit in the apartment where the music was composed. We get to watch the elder Mechner play Wagner's leitmotifs from Der Ring des Nibelungen on the family piano, then compare those directly to what they achieved on the far less musical Apple II.

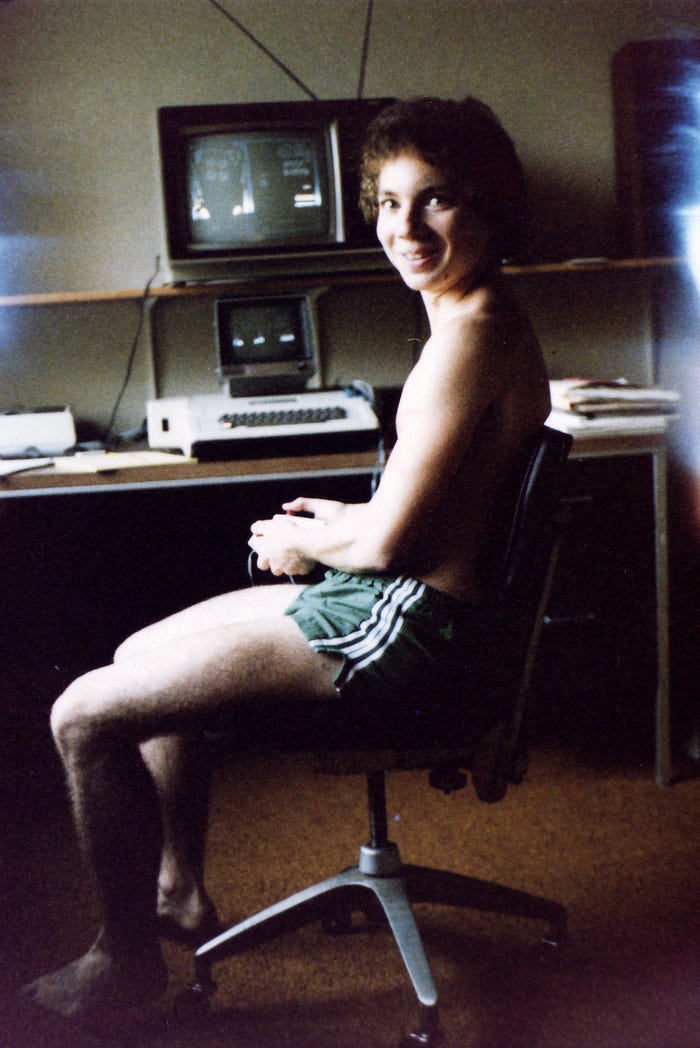

The Making of Karateka benefits from even more explanation and documentation, largely culled from Mechner's journals and other personal effects (on loan from the Strong National Museum of Play). In one clever interactive section, players can overlay original Super 8 film of Francis Mechner running in his wife's karate gi, hand-drawn versions of each frame (better known as "rotoscoping," a technique Mechner had been fascinated by ever since seeing it in classic Disney films), and multiple passes of pixel art to turn those frames into crucial in-game animations. The collection also chronicles Mechner’s crucial pre-Karateka work: a series of Asteroids clones that he eventually turned into a unique, unfinished game called Deathbounce.

"Karateka was really the culmination of a six-year timeframe," Mechner says. "From getting my first Apple II in 1978 as a freshman in high school, I made games, and each time I kind of hoped that it would get published. All of those 'almosts,' each raised the bar a little bit. All that time, the industry was evolving very fast as I was trying to evolve as a game developer. So Karateka really brought together everything I’d learned on the previous attempts—and it makes the most sense in the context of those earlier games."

When pressed on this point, Mechner offers a rare tinge of regret: “Especially when I was a young developer, I would have loved to have an exhibit like [Making of Karateka] about any game I had played and liked! At age 16, 17, I was in the dark. Not just about the technical aspects, but also the human side of programming. How does it work? What’s your relationship like as an author with the publisher, with players, with other people? To see somebody else go through that, all the emotional ups and downs. The excitement, the disappointment, the blind alleys: I love that.”

Even Mechner has something new to look forward to in the collection: newly remastered versions of Karateka and Deathbounce, which each pull from Mechner's recovered source code, notes, and prototype disks to make something new-yet-authentic. Karateka’s remaster includes a director’s commentary where project lead Mike Mika claims that he didn’t quite approximate the original Karateka AI. He describes his struggle to change timings from the weak Apple II to modern machines and still replicate the old games’ feel.

This remaster was completed with zero input from Mechner beyond his blessing, and he admits he doesn’t have a good answer to the original game's AI: “There’s pretty few moving parts in the fighting AI. I really think it was three or four parameters for each guard, so it was about finding different combinations of those four numbers that would give each their own personality. I haven’t looked at that code in 40 years, but that’s how I remember it."

Mechner confesses that his own memory is quite faulty, which is why he's glad he kept such copious notes and journals as a younger programmer and artist. At this time, he was inspired by how much he devoured other artists’ journals, including Steven Soderberg’s journals about the film sex, lies, and videotape and Michael Palin’s records about the early period of Monty Python. "It’s not like writing a memoir, where you look back and shape your story into some version of what happened," Mechner says. “It’s what you wrote on that day."

He compares that to the steel-trap memory of one of his games industry peers: John Romero, whose recent memoir chronicles a much different kind of game-making upbringing. “He's got some kind of photographic memory,” Mechner says while raving about the book. “He can recall entire conversations 20 years later.” In a funny turn, Romero’s memory and Mechner’s propensity to save all of his notes and letters collided roughly a decade after Karateka launched. The first time they met in person, at a GDC in the 90s, Romero's first words to Mechner were to ask, "Did you get the letter I wrote you in 1985?"

Indeed, he did—and that letter, full of specific programming questions about Mechner handled scrolling on the Apple II, is now available inside The Making of Karateka for everyone to read this many years later. (Romero sadly lost Mechner's original reply letter, which he regrets: "It would refresh my mind about how I did the scrolling!" he jokes.)

"John [Romero] had to pursue his love for games and programming in the face of parental resistance," Mechner continues. "He was flat-out told, 'you're not allowed to go to the arcade or play video games.' I didn’t have that." He again lists off the ways his mother, father, and brother each contributed to his earliest games, among others, perhaps as outreach or advice to budding game developers (and their families) going forward. "All of my games were really a community that I had around me. It's really valuable for creative people who work alone to have other people to bounce their ideas off of."

This appreciation for community and family will pay forward in 2024 when his graphic novel memoir about Mechner and his father will be published in English, titled Replay. (There’s a French version already in circulation, if you're bilingual and can’t wait.) A few pages chronicle moments in the development of Karateka and Prince of Persia, but much of the book is about his father's birth in Vienna and their Jewish family's escape during Anschluss in 1938. He can't help but see his own tendencies reflected in that story: "His family's odyssey of separation and reconnection is interwoven with my stories as a game developer, which are a lot less exciting, but still connected," Mechner says. "The games, like other efforts in our home, were somewhat family projects. That's the connective tissue."

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like