Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Games aren't stories per se, but stories -- and sometimes excellent ones -- emerge from players' interactions with their systems.

December 1, 2021

Author: by William Dyce, lead designer at Amplitude Studios

Game Developer Deep Dives are an ongoing series with a goal of shedding light on specific design, art, or technical features within a video game in order to show how seemingly simple, fundamental design decisions aren't really that simple at all.

Here, lead designer William Dyce offers an in-depth look into how the team at Amplitude Studios crafted the diplomacy system for Humankind, Amplitude Studios' 4X Historical Strategy game where players "re-write the entire narrative of humankind – a convergence of culture, history, and values that allows you to create a civilization that is as unique as you are."

Players will often declare, tongue firmly in cheek, that the strategy game with the best diplomacy they know of is Dominion: a game where players are entirely free to make and break deals and to stab each other in the back.

Dominion: here we see a group of friends in the process of becoming a group of enemies.

The implication is that games with formal diplomatic gameplay systems are unduly restricting player expression. Why then do the developers of games like Civilization, Total War and Crusader Kings insist on designing and implementing these systems?

Total War Three Kingdoms: why can't we just agree via chat that I'll send them some money every turn?

We had this question very much in mind when designing diplomacy for Humankind. After all, it's generally a mistake to blindly lift mechanics from other games, as the same rules might make no sense in the context of a new game: shooting monsters is fun in Doom, for instance, but would it be fun in Portal? As well as helping us to design the game's diplomacy system, the answers we found provided a novel way of looking at game experience design as a whole.

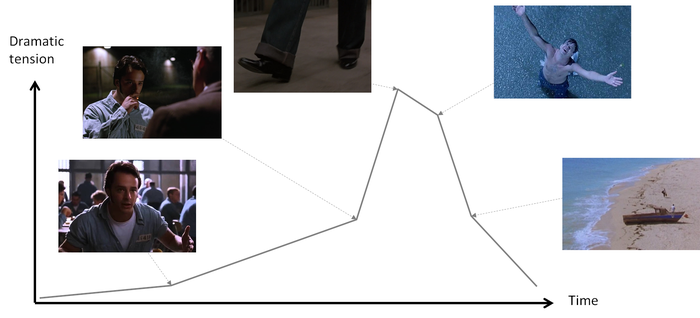

How so? Patience. First I want you to imagine a heist movie shot from the point of view of the bank manager: we, as the audience, follow her as she goes about her day, and are just as oblivious as she to the fact that her bank is being robbed right under her nose. 90 minutes of boredom later we watch her open the safe and find it empty. Roll credits.

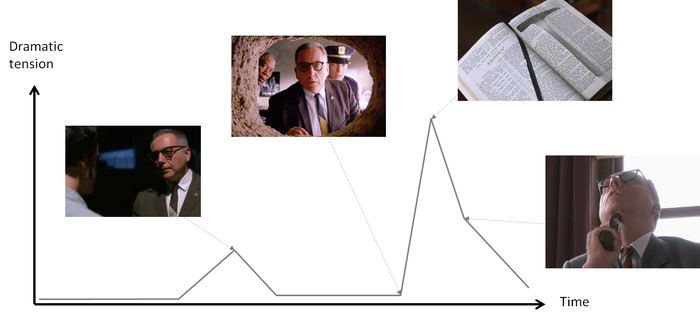

Imagine the Shawshank Redemption shot entirely from the point of view of the warden. Sorry for the spoiler.

Now, I think you'll agree that this is not a good film. Brian Upton, whose book I heartily recommend, would probably argue that such an experience is "unfair," from the point of view of interpretative play, as the "player" was not given the information necessary to guess where things were heading in the possibility space.

Yet, for many strategy game players, the first inklings that a neighbour harbours expansionist ambitions come when hundreds of tanks suddenly roll out of the fog of war and into their capital. Is this not equally boring and unfair?

That line from the end of Watchmen springs to mind: why tell you my plans if there's time to counter them?

Games aren't stories per se, but stories – and sometimes excellent ones – emerge from players' interactions with their systems. Our job as designers is ultimately to make sure these stories are interesting, or at a minimum that they are “fair” from the point of view of interpretative play.

Good storytelling has a lot to do with setting up and paying off expectations: for the player to have a fighting chance of guessing how a fictional world is going to evolve, there need to be constraints on how it can evolve as well as characters or agents with both clear motivations to prevent or enact change. There also need to be well-defined sets of action verbs that allow them to enact change in various limited and predictable ways.

In Endless Space 2 a lot of effort went into making the AI irrational: it just loves telling you its plans.

If you're playing a strategy game with sociable human opponents who speak the same language as you, then the characters in your story, the opposing players, will betray their intentions through tone of voice, word choice, hesitation, and so on. They might be people who you know, with personalities you're familiar with, and they will have access to social verbs like “threaten”, “goad”, “promise”, “flinch”, “plead” and “bluff” without the game's developers having to do anything. Given that the vast majority of players play offline against the AI, however, formal diplomatic mechanics are necessary. Without them the only action verb that can exist will be “smash” ... which doesn't make for a great deal of variety in terms of the types of stories that can be told, so doesn't lead to much in the way of interpretative play or “froth” as players excitedly recount the events of their playthrough. I'll only tell friends about a play experience if I'm confident something unique happened to me.

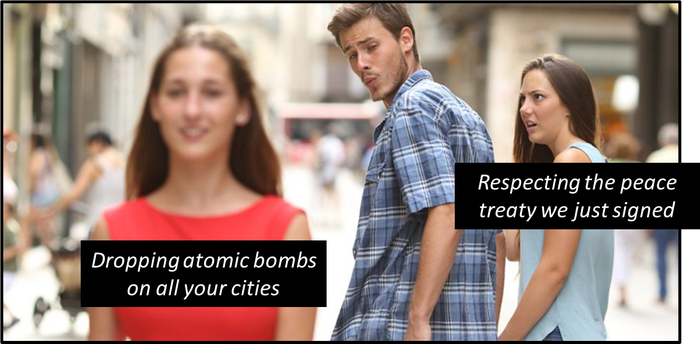

Variety, then, is important for “frothy design”, but predictability is too. Again, this has to do with “fairness” from the point of view of interpretative play; for more linear media we'd talk about Chekov's Gun. In a competitive game, it's a terrible idea to reveal your plan while there's still time to counter it. As a result, a purely rational player (be they a human or an AI) will deliberately behave in an unpredictable, unsatisfying manner if permitted, at least from the other players' points of view. Diplomatic mechanics can push players to be more predictable, and thus provide a more satisfying experience for their adversaries.

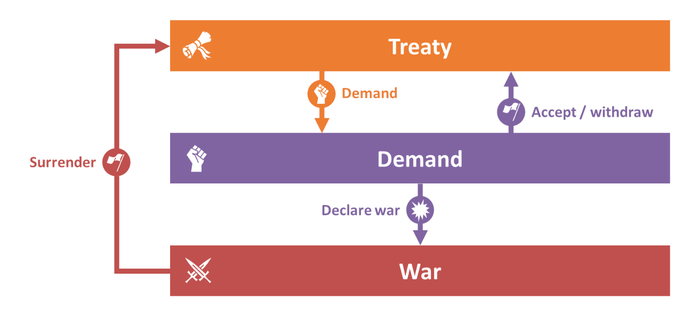

The basic premise: a demand leads to a state of embargo, cutting off trade to force the other side to accept it.

Our initial focus for Humankind's diplomacy, then, was to ensure that players always saw wars coming in advance and that they knew precisely why a war was being declared and what was at stake, with a good variety of both casus belli and war reparations to choose from. Player actions generated tokens called “grievances” that could be “played” in order to make a corresponding “demand”.

An early version of the grievances, back when demands rather than war support was used to justify war.

For instance, if you built a military base near my borders, I would receive a grievance that could be cashed in to demand that you remove said military base. If you refused to do so or didn't respond within 10 turns then I could declare a “just war” on you in order to pursue my demands by force, and if I won the war my demands would be applied: in this case your military base would be dismantled.

The trouble with this first iteration was its lack of flexibility: players often didn't have the grievances they needed to justify a declaration of war so felt unduly passive, reactive, and sometimes just plain restricted. The need to wait for 10 turns was also frustrating; it served as a sort of Chekov's Gun for the victim, but would-be aggressors didn't find deploying the verb “wait” on a regular basis much fun.

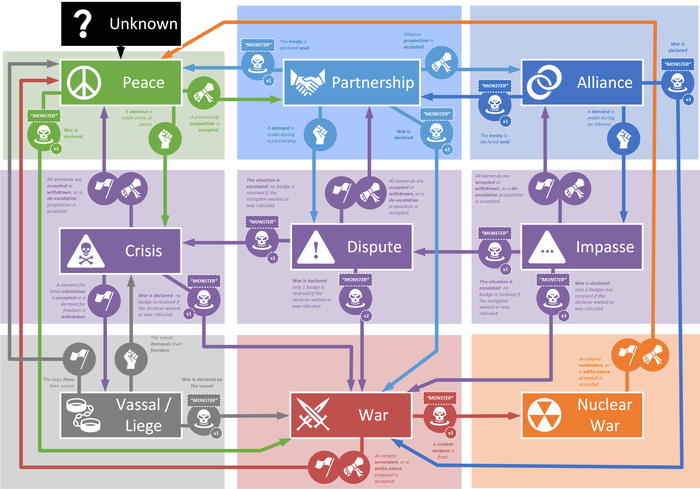

Things got terribly complicated, but made for a very pretty one-page (or rather 3x3 A4 page) design document.

Most importantly, the system didn't behave in a satisfying way for conflicts like the Franco-Prussian War, where the defender completely turned the tables on the attacker and ended up imposing various concessions on them that weren't on the table when war was originally brewing.

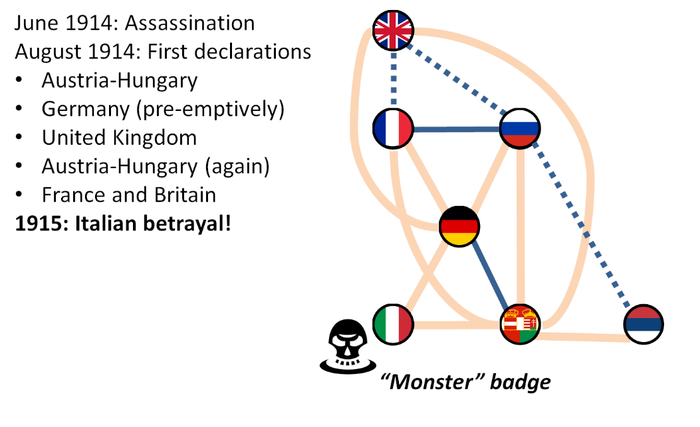

For the following iterations we decided to use various real-world conflicts like the World War 1 and 2 and the Cuban Missile Crisis as a sanity check: it was important to us that it be possible to recreate such conflicts in-game, but also that it be a rational decision, given the game rules, for the historical actors present to perform the actions they did in the sequence they did.

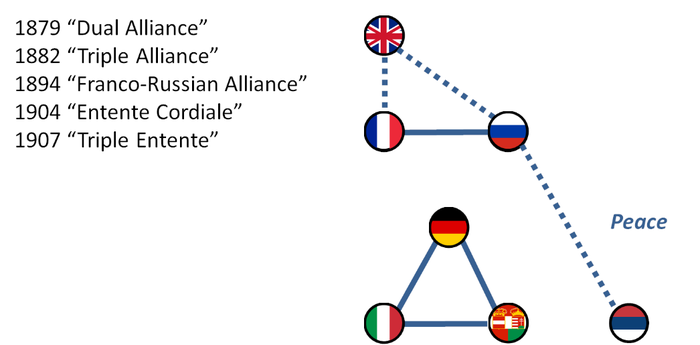

The blue lines are alliances. Yes, I know, there was more to the Entente Cordiale than just a peace treaty.

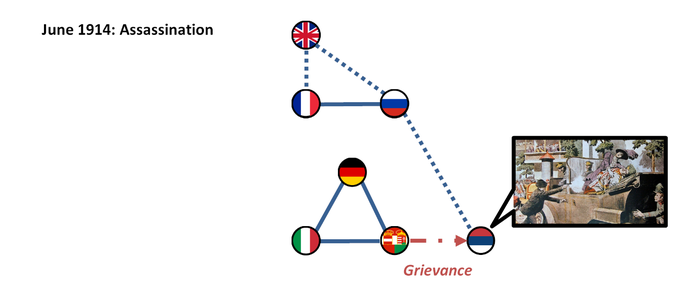

Admittedly don't have a “political assassination” grievance in the game… yet!

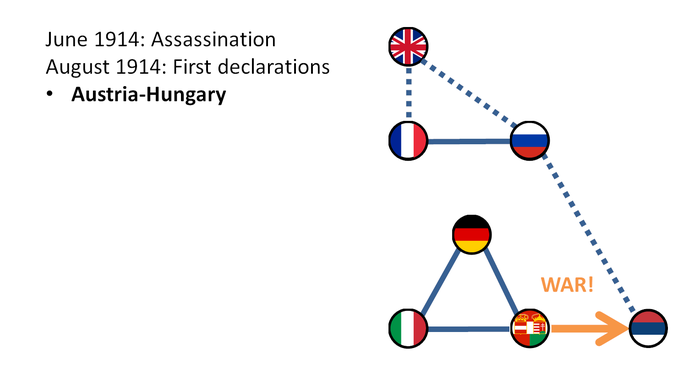

In other words: World War 1 should emerge naturally from players' interactions with each other as arbitered by the system.

Needless to say, we've skipped a few steps between the previous images and this one.

Confident that this kind of thought experiment would help catch any strange behaviours before they were implemented, we moved to address the other issues we'd identified. We considered adding more grievances to ensure that player always had one or two to hand, but decided to cut out the middleman and add “demand submission” and “demand tribute” actions instead, on a cooldown. This meant that players were never more than 10 turns away from a just war, but that to acquire territory they would still need to wait for a grievance to trigger, as there was no default “demand territory” action.

Players still felt plagued by arbitrary wait times, however, and didn't appreciate having to return the cities they'd conquered at the end of the war just because they had no good justification for keeping them. There was also a serious lack of nuance in the way wars were resolved; you would either win a war outright and see all of your demands met or lose the war outright and suffer your opponent's – there was no middle ground.

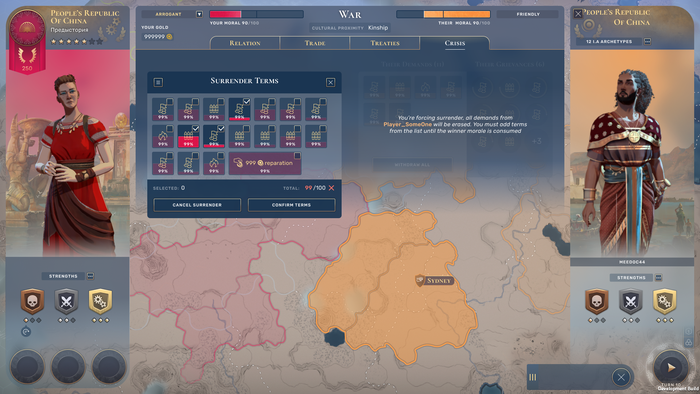

We eventually had to admit to ourselves that we had fallen too far in love with the idea of having grievances that defined demands which then defined spoils: this wasn't doing us any favours. The rule seemed simple and elegant on paper, and allowed for one-click war resolutions, but to accurately model many real-world historical conflicts we needed to allow surrenders to be negotiated, with an attribution of war reparations dependant on how well each side had fought.

This was a mock-up created when we were first discussing modular surrenders.

Exactly where demands would fit into this new system took some thought, as we still wanted the demands made at the beginning of the war to have an important impact on the spoils received at the end of it. Ultimately, we decided to let players spend “war score”, earned by winning battles and capturing cities, to choose which demands to apply. Any excess was then converted into monetary reparations. Later, we added the option of converting part of this excess into demands for territory or submission, and removed the demand submission and demand tribute actions.

“War score” had existed since the initial version but, redubbed “war support”, it was now used to provide a more flexible replacement to the fixed number of turns that player originally had to wait before declaring a just war; players would earn war support each turn they had demands left unanswered. This meant that other systems could play into the pre-war propaganda we wanted to model, with certain countries better than others at getting their populations “aboard the war train”.

Here's what the diplomacy screen looked like at release.

The question of personal freedoms is a tricky one in the real world: we might say that one person's freedom ends where another's begins, but in practice defining the exact limit between my freedoms and yours requires complex regulation and the occasional legal battle. The role of diplomatic mechanics in strategy games is similar to that of regulations: by acting as an obstacle to some players they serve to ensure that the others have a more positive experience.

Humankind's diplomacy has tended to be “deregulated” a little bit more with each iteration though, doubtless for the better. I don't believe that this is an indictment of the “frothy design” theories laid out in the introduction to this piece, as the fundamental principles have remained intact at launch. It does go to show, however, that no amount of theoretical proof can serve as a substitute to playtesting! And so, if I had to change anything, I would spend less time waxing lyrical about “narrative coherence” and more time building and running paper prototypes. That might have reduced the number of iterations necessary to arrive at something we're happy with, and resources could have been allocated elsewhere.

With close to 1M players within the first month we've been able to collect an enormous amount of feedback, and Humankind's diplomacy will without doubt keep being tweaked and polished moving forward. In approaching its design from the point of view of storytelling we have built solid mechanical foundations for years of live support, and while the path followed has been tortuous at times I'm very proud of what we've accomplished for release.

The actual Shawshank Redemption works, among other reasons, because events are set up and paid off.

You'll notice that I've only talked about grievances, demands and wars in this piece: there's a lot more to Humankind's diplomacy, but in the interest of keeping this relatively short I'll avoid talking about how treaty propositions evolved for the now. If you like this post please let us know, and perhaps we'll write another.

You May Also Like