Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Gamasutra is partnering with the IGDA's Preservation SIG to present in-depth histories of the first ten games voted into the Digital Game Canon, this time providing a comprehensive overview of Sid Meier's influential turn-based strategy opus Civilization, including an interview with Meier himself.

July 18, 2007

Author: by Benj Edwards

[Gamasutra is proud to be partnering with the IGDA's Preservation SIG to present detailed official histories of each of the first ten games voted into the Digital Game Canon. The Canon "provides a starting-point for the difficult task of preserving this history inspired by the role of that the U.S. National Film Registry has played for film culture and history", and Matteo Bittanti, Christopher Grant, Henry Lowood, Steve Meretzky, and Warren Spector revealed the inaugural honorees at GDC 2007. This latest piece follows the carrer of industry icon Sid Meier as he established himself as one of the most important contributors to PC gaming with the iconic turn based strategy epic Civilization.]

By 1990, Sid Meier had cranked out flight simulator games for as long as he knew how, at the request of his boss and partner. But Meier's life, and the world of computer games around him, had changed so much since the two men entered the market in 1982. Meier felt the undeniable urge to broaden his horizons as a designer; it was time to move on to greater things. Despite considerable opposition within the very company he co-founded, Meier broke the status quo and changed the course of computer strategy games forever. As the naysayers sank in his wake, he engineered lasting success and achieved design immortality with an epic game based on nothing less than the history of mankind.

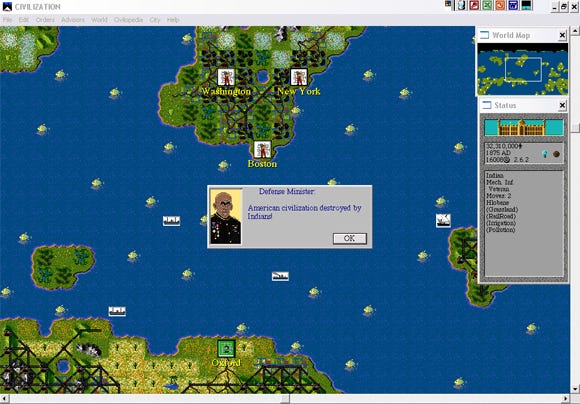

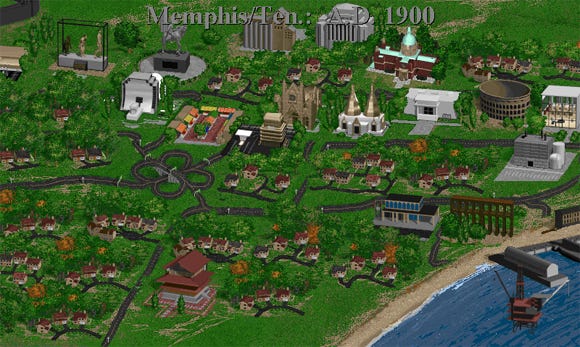

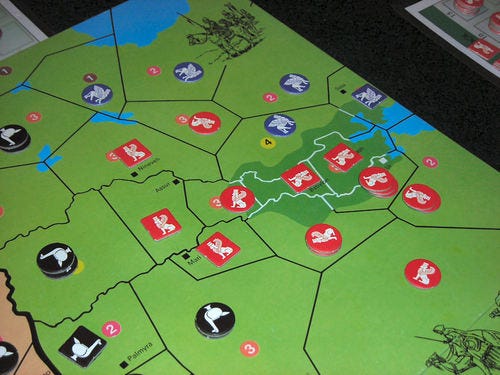

Few games are as addictively fun and as infinitely re-playable as Civilization, a turn-based historical strategy game where a player single-handedly guides the development of a civilization over the course of millennia, from the stone age to the space age. The game feels uncannily accurate, as if it actually represents the way the world could have unfolded if the course of history were nudged over just a bit. Civilization's designer, Sid Meier, somehow distilled, condensed, and codified the rules of humanity's post-agriculture development into a three-megabyte IBM PC computer game, with shockingly good results. For that achievement, many critics recognize Sid Meier as one of the greatest software designers in history.

Meier's historical classic finds itself in good company among gaming innovators like Tetris, SimCity, and Rogue with the inclusion of random play elements that make each sitting unique. Civilization marks especially high in this regard: between random map generation, multiple ways to win, up to 15 additional computer-controlled civilizations, and seemingly endless combinations of paths to pursue, Civilization's emergent gameplay results in a whole new gaming experience every time. "The fact that there are so many different ways to play, and that they all seem interesting and fun, leads you to want to play again after you finish the game," said Meier in an interview.

Playing Meier's classic again is always tempting, assuming that we've actually eaten since sitting down for the last game, perhaps six or ten hours before. Civilization's addictiveness is legendary. So much so that it even has a name: the "one more turn" phenomenon. While playing Civ, there's always something cooking in the pot, something to look forward to. In your next move, a unit or building could be completed, a new city founded, or an exciting technology developed. "There was never really a good place to stop playing," says Meier. "I've often found myself playing and then realized I'm late for a meeting. So I've been exposed to the phenomenon myself."

How did Meier conceive of and create such a powerful, yet deceptively simple simulation of world events? To understand the full story on this incredible game, we'll first have to take a quick journey back into the early days of computer gaming.

Sid Meier met Bill Stealey in 1982 while they both worked at General Instrument, a large electronic component manufacturer. Meier, a talented young minicomputer programmer for GI, had recently acquired his first personal computer, an Atari 800, and was already creating primitive games for the machine in BASIC. John Wilbur "Bill" Stealey, a management consultant that held a side career as a fighter pilot with the U.S. Air Force Reserve, had also recently bought an Atari 800 to play Star Raiders.

The two crossed paths through the company and started chatting. Stealey shared his old Air Force stories, while Meier talked of his coincidental plan to write a flight simulator game for the Atari. As a die-hard fighter pilot, Stealey's interest was inextricably piqued, and he proposed going into business with Meier. The exuberant, outgoing Stealey (nicknamed "Wild Bill" by his friends) would cover the marketing and administrative duties, while the quiet, introspective Meier would write the games. It was a classic pairing of complementary personalities; neither man could have done it alone, but together, they formed a perfect team. The pair founded MicroProse Software in 1982 with Stealey as president, a position he would hold throughout remainder of the decade.

At the time of Civilization's conception, 35-year old Michigan native Sidney K. Meier led an idyllic life with a dream job. "I was having a wonderful time as a game designer at MicroProse," says Meier. "It was really what I loved doing, and still love doing." Married with one child on the way, Meier settled near Baltimore, Maryland, close to company headquarters. MicroProse had been in business for eight years, and things were going well. "We had assembled a pretty good group of designers, programmers, and artists," recalls Meier. "That represented the golden years of MicroProse, where we had some good games and we really felt we could tackle new topics and give new things a try."

During those halcyon days of the nascent PC game industry, computer game design had not yet been restrained by the single-minded adherence to narrow, hit-proven genres or skyrocketing hundred-million-dollar production budgets of today. Instead of looking at focus groups and market conditions to guide his designs, Meier says he'd simply propose potential topics for games, like "pirates," "trains," "civilization," or "the Civil War," and then act on them. He recalls the period fondly, as if pining for simpler days: "There was a lot more experimenting. The graphics and the sound technology were limited, so the investment wasn't so high to make a game. It was a little less risky, so we could take a chance with games because they didn't cost as much money."

For some years before, Meier had been working with a collaborator at MicroProse by the name of Bruce Campbell Shelly. Around the time of Civilization's development, the recently-married 42 year-old Shelley had been making games professionally for eight years. As a veteran of Avalon Hill board game development, he seemed like the perfect fit for Meier's strategy games. "He had actually done the conversion of Francis Tresham's 1829 railroad game and turned it into 1830 for Avalon Hill," recalls Meier. The board game market, under onslaught from the new field of computer and video games, wasn't doing too well in the mid-1980s. "Board games were at a tough point at Avalon Hill," remembers Shelley. "I didn’t think I had any future there. When I found out the company that had created the Commodore 64 game Pirates!, I looked into trying to get a job there. I thought computer games had more of a future."

He joined MicroProse in 1988 and worked with Meier on important projects like F-19 Stealth Fighter, Railroad Tycoon, Covert Action, and, of course, Civilization. "I was on the F-19 game right away, and that took up much of my first year," Shelley adds. In his second year, he worked on porting of existing games to other platforms. "Somewhere in that year, [Meier] asked me to become his assistant designer, which was a great opportunity," says Shelley. Since Meier was a co-founder of the company with an impressive resume of games already under his belt, Shelley was "predisposed to be impressed" by the humble programmer. Shelley found his new boss's subtle sense of humor and keen intelligence compelling. The two quickly gelled and became an inseparable team -- the "A-team," as they were known by some in the company.

The story of Civ's genesis is neither simple nor straightforward. It's clear that a large confluence of inspirations ultimately combined in Meier's brain to form Civilization. As popular culture continually feeds on itself, the ingredients and influences that make up any particular work tend to be varied and complicated. In this case, add three parts Risk, two parts Sim City, one part Railroad Tycoon, and a heaping teaspoon of Sid Meier's design genius. Stir in a little Bruce Shelley for taste, set your oven to "Wild Bill Stealey," and out comes Civilization.

One of the most repeated and touted inspirations for Sid Meier's Civilization is the earlier Avalon Hill board game of the same name, designed by Francis Tresham for Hartland Trefoil in Britain. While Meier had no doubt heard of the game prior to 1990 through his connections with Bruce Shelley, he insists that the influence is not as strong as some claim. "I had not played that before I did Civilization," says Meier. "I played it later. I remember there were some cards and trading. It was more ancient; it didn't really come into any sort of modern or medieval times."

But connections, however thin, were there: Bruce Shelley had not only worked for Avalon Hill, the American publisher of Tresham's Civilization, but he created the American localization of Tresham's 1929 railroad game, a game which served as an admitted inspiration for Meier's earlier Railroad Tycoon. It should come as no surprise, then, that Shelley was intimately familiar with Tresham's Civilization. "I had played it many times," recalls Shelley. "I believe Sid had a copy of the game and looked at the components. I owned the original board game, but don't recall if I brought it into the office."

Regardless of the actual influence Tresham's classic had on Meier, players familiar with Avalon Hill's Civilization commonly note the significant difference in approach between the two, making Meier's software creation uniquely his. Soren Johnson, lead designer of Civilization IV, weighed in with his opinion on the issue in an interview for Civilization Chronicles: "The board game [is] quite linear. The difference in Civilization is that it branches, and I think that’s what the board game didn’t have."

Still, MicroProse wasn't willing to take any chances with any similarities between the two games; the company licensed the title "Civilization" from Avalon Hill for a small sum, delaying any legal wrangling over the title or intellectual property for nearly a decade.

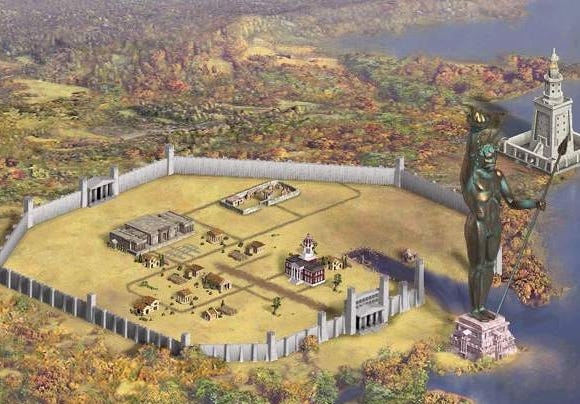

According to Meier, his Civilization actually started as a glorified version of a favorite childhood board game. "It was kind of like Risk brought to life on the computer," muses Meier. "That was the original idea. And then we added the technology and the whole sense of history to it." Meier was also a big fan of an early computer game called Empire, which combined Risk-like world domination with intricate city management. "At one point, [Meier] asked me to make a list of 10 things I would do to Empire to make it a better game," says Shelley. "That was some of his research on Civilization."

Groundbreaking games like Bullfrog's Populous and Will Wright's SimCity had recently invented the "god game" genre, where an all-powerful overseer, controlled by the player, directs the course of a population from an overhead view. With their release in 1989, both games -- especially SimCity -- had a profound effect on Meier as a game designer. SimCity taught him that a computer game didn't have to be about chaos and destruction, but could focus on "building things up" instead. Wright's masterpiece provided a vivid illustration that a game could be a "software toy" that let a player experiment with and manipulate a virtual world without a specific objective.

That lesson, along with Meier and Shelley's love of trains, served as the basis for Sid Meier's Railroad Tycoon, an overhead, real-time track building game released in 1990. As Meier's first non-destructive "god game," Tycoon marked an important turning point in his design career. Nearly all the games he made before Tycoon had been combat flight simulators or military strategy games, keeping perfectly in line with the desires and comforts of MicroProse's military-fixated president. But the growing differences in direction between the two founders -- Meier's need to branch out as a designer, and Stealey's laser-like focus on combat simulators -- led to major changes in the structure of the company they founded.

At the time Meier created Civilization, he wasn't an employee of MicroProse at all. He was, in fact, a private contractor.

Around the turn of the 1990s, Bill Stealey and other MicroProse executives pushed the company into risky new markets like home game consoles and arcade video games. According to Shelley, Meier didn't like the direction the company was heading at the time. He smelled trouble and wanted out. "We didn't learn that Sid was a contractor until the company went public," wrote Bruce Shelley in a recent email to the author. "In the documents related to the IPO, we learned that Bill Stealey had bought out Sid some time earlier."

In Meier's likely-exclusive contract with his former employer, he received money up front for game development, a large lump sum when a game was delivered, plus royalties on the sales of each copy after release. A new vice president of development replaced Meier's former role at MicroProse. Unfortunately, the new VP didn't receive personal bonuses on Meier's releases, giving Sid Meier titles a low priority in the company. Regardless of the rough patches in his relationship with MicroProse, Meier retained a soft spot in his heart for the company he co-founded. He was still committed to batting for the home team, even as MicroProse began to flounder.

Meier began coding Civilization on the IBM PC in early 1990, soon after MicroProse killed a sequel to Railroad Tycoon that he and Shelley had been working on. His design work was intense and nearly all-consuming: he kept a legal pad by his bedside at night so he could make spontaneous notes on game ideas for implementation the next day. Meier handled most of the programming on Civilization himself, even doing all of the early artwork for the game (Some of his art survived to the final version). But Meier still needed help with a vital part of the game's design.

"Sid gave me the first playable [Civilization] prototype in May, 1990, on a 5 1/4" floppy disk," recalls Shelley. Through the course of their two-year collaboration, Meier and Shelley had developed a unique "iterative" software development cycle. Meier would whip up a working prototype of a game and hand it off to Shelley. After extensive testing by Shelley, the two men would discuss the shortcomings of the current prototype.

"Out of that conversation, [Meier] would revise the prototype in the afternoon and leave a new version for me to test in the morning," recalls Shelley. "I usually beat him in to work and would have play-test feedback ready for discussion." The duo would continue this cycle repeatedly, revising and refining the game until it was as near-perfect as they could create within their limited resources and time constraints.

Meier remained remarkably private about Civilization during the early development process. "He rarely let anyone else play the games until he thought they were pretty solid," says Shelley. For months, Shelley was the only person allowed to see prototypes of Civilization in action. Other MicroProse employees commonly visited Shelley's office to bug him about the duo's current project, pestering him not to be stingy with the latest Sid Meier masterpiece; they were anxious to try it out themselves.

But Meier kept a tight lid on the project until he was ready, trusting solely in Shelley's criticism and preferring his feedback to all others. "He must have relied on me to be his sounding board, to represent average gamers around the world," adds Shelley. Meier recalls their fruitful collaboration well: "[Shelley] was very, very helpful. He was the guy who would play it and we'd talk about what was working, and what wasn't working. He served as a second opinion on everything."

Development of Civilization took place in two major phases. The first version Meier created did not feature turn-based gameplay, but a real-time model that borrowed significantly from its spiritual predecessor, Railroad Tycoon, and more importantly, SimCity. The prototype featured a SimCity-like zoning approach, where the player would demarcate areas of the world for agriculture or resources that would gradually fill in over time as the player waited. Ultimately, Meier found the real-time play style severely lacking in excitement. "It quickly became apparent that watching the civilization grow was like watching paint dry," recalls Meier. "The action was so [dull] that after a little bit of that, there might have been a game that intervened."

During a rare video interview with Computer & Video Game Magazine in 1994, Sid Meier talked about delays in the development cycle:

"There are a number of occasions when a game has gone six months into development, and we said 'This really isn't progressing the way we want it to.' Civilization was kind of like that. We worked on it for a couple months and it was kinda neat, but we went and did something different, and then came back to it."

According to Shelley, it wasn't just the dull gameplay that made them put Civilization on the backburner. The realities of the business world came crashing through their door. During the lull in enthusiasm for the new game, upper management at MicroProse learned of the latest project that the Tycoon boys were working on. They weren't impressed.

Bill Stealey, the USAF pilot and academy graduate, understood flight simulators. He had built his company on the backs of titles like HellCat Ace, Solo Flight, F-15 Strike Eagle, AcroJet, Gunship, and F-19 Stealth Fighter. The genre worked for Stealey in the past, so he saw no reason to change a winning strategy. "He wanted a new [flight sim] every year," remembers Shelley. But Meier grew restless and bored of churning out military sims at the behest of his partner, one after another, after another. That's when Meier threw off his reigns and broke the company mold with Railroad Tycoon. Meier's move made Stealey thoroughly uncomfortable. The president had no interest in Tycoon as a game, and if it had not sold so well, future non-military games (even if they were Sid Meier games) would have had no chance of release at Stealey's company.

Like Railroad Tycoon, Civilization faced a similar uphill battle with MicroProse management. "I recall that Civ was not a game that Bill was excited about or interested in," says Shelley, who believes that Civilization might have simply been canceled if Meier had been an employee. In that case, MicroProse would have held absolute budgetary power over the project.

Despite his reservations, Stealey's faith in his original partner came through, as Shelley recalls: "I seem to remember hearing Bill say stuff like 'I don't get the game, but I trust Sid, so we're going with it'." But before the A-team could complete Civilization, they had to compromise: Stealey wanted Covert Action completed first. The two developers had previously put the action-packed spy game aside to focus on Meier's last capricious diversion, Railroad Tycoon. "It was really frustrating to be told by management to stop working on [Civilization] in favor of something they wanted instead," says Shelley. "I don’t think management had much of a clue about what it was until it started selling."

After completing Covert Action, Meier and Shelley turned their attention back to their pet project. In phase two of development, Civilization took a page from Shelley's board game roots and became turn-based, losing the zoning process while gaining a more militaristic, Empire-like edge. Meier invented individual units to control and move around the playfield. "You had settlers who irrigated and could change the terrain and found cities," says Meier, "so we took the things that were zoning oriented and gave them to the settler." The more hands-on approach felt just right, and the basic gameplay of Civilization, as we know it today, was born.

During this phase, Meier also created the famous "technology tree" that allowed a civilization to advance in capability over time, while still presenting interesting, non-linear choices to players. "The technology began as a way of gradually opening up possibilities as you go about the game," says Meier. Players had to decide a course to pursue with specific technologies early in the game and stick with it to get where they wanted to go. Later, they could go back and develop older technologies or trade for them with the computer-controlled civilizations.

With a game this deep, you'd think Meier put hundreds of hours into historical research, but it isn't so. "I tried to use fairly well-known concepts, well-known leaders, and well-known technologies," says Meier. "It wasn't intended to be 'bizarre facts about history.' It was intended to be something that anybody could play." When pressed, Meier does admit that he occasionally consulted a few "timeline of history" books, just to make sure he got the chronology of certain developments correct, or to make sure he spelled leaders' names right. But for the most part, the well-read Meier drew historical facts from his reserve of personal knowledge and understanding of history. Regarding research, Shelley proudly remembers a timeless lesson Meier taught him about historical game design: for a game to be fun, the details needn't be too in-depth or cerebral. "Everything we needed was pretty much available in the children’s section of the library," says Shelley.

With the game mostly realized, Meier and Shelley had to get the rest of MicroProse on board in order to ship Civilization on schedule. They mainly needed help from the art department, but they had trouble securing it due to the low priority Meier's games received in the company. "Remember that the VP of production got no bonus for what Sid published," adds Shelley, "So he wanted to put resources on stuff he was being paid for. It was a struggle to get the people we needed to finish Civ." Eventually, if only begrudgingly, they received support from MicroProse management to finish the game.

Meier submitted Civilization to the MicroProse play-testing department for final gameplay tweaks. At that point, the biggest issue with the game was the enormous original size of the map. Meier recalls the problem: "I remember slogging across this continent when I was playing and I had my tanks against the lame-o units of the other guy, capturing city after city and thought, 'This map is just too big'." The huge map was too overwhelming to new players, and it slowed down the pace of the game considerably. After reducing the map size, Meier learned that he could "have the same amount of fun in half the space," a lesson he took with him to future projects.

Shelley and Meier also cut out a whole section of the technology tree, complete with minor technologies, for the sake of simplicity. "A lot of what we did was done to make the game tighter and smaller," says Meier. Ironically, Shelley regrets not having the time to add more technologies to the game and balance them out, but Meier feels the number of technologies was just right, leaving room for future versions of Civilization, like Civilization II, to expand upon and improve the original. Meier and Shelley devoted most of the remaining development time trying to even out the technologies they did have as perfectly as possible. If they added new units or technology haphazardly, or took certain ones away, it would throw the game wildly off kilter. "We realized that the game was easy to break," says Meier. They tread carefully to ensure an authentic and "fair" feel to the game.

As a finishing touch, Bruce Shelley wrote the comprehensive and unprecedented Civilopedia, an in-game reference encyclopedia on each unit, technology, building, resource, type of terrain, and form of government. Shelley also wrote a massive, detailed manual, included in every box, that he and Meier are still proud of today. "In those days, MicroProse manuals were 200 pages," remembers Meier, "and I think they added a certain special quality to the games. You felt like they were substantial and worth playing."

"I remember many meetings when I reported we could not meet the production schedule without help," says Shelley. "The game shipped late at least partially because other projects were given a higher priority." The reluctance of MicroProse management to fully support Civilization was incredibly frustrating for both Meier and Shelley. "I thought it was nuts to hold back on what everyone in development agreed was going to be a big hit," adds Shelley. "I was really incensed when our bonuses were shaved considerably because we slipped, which I thought was management’s decision." Thankfully for us, it did ship. Against sizable odds and obstacles it had faced throughout its entire development process, Civilization went on sale to the public in 1991.

MicroProse devoted little money into the promotion of Civilization, so the game had to rely heavily on word-of-mouth, through fans on the street (and on the electronic bulletin boards of the day), for marketing and public awareness. Fortunately, Civilization proved so irresistibly fun that it suited itself perfectly to the gamer grapevine. It wasn't long before the gaming press routinely recognized the latest Meier-Shelley release as "Strategy Game of the Year" in popular computer magazines of the time, in both Europe and the United States. As word of the game spread, sales of Civilization soared, surprising not only MicroProse management, but even the creators themselves. "I don’t think at the time I thought it would become recognized as one of the best PC games of all time, or that it would live on through multiple revisions, perhaps forever," recalls Shelley.

Most deservedly, MicroProse was reluctantly forced to eat crow when they witnessed the phenomenal success of a game that they repeatedly tried to hold back. "A couple of months after [Civilization] had been out, I got a call at home from Bill Stealey," recounts Meier. "He had been at an awards thing, I don’t remember which one, and he had been living it up a little, and said, “We won an award for your game!”

MicroProse ultimately released two arcade games in the early 1990s that did not fare well in the marketplace, including a fully 3D, coin-operated adaptation of Sid Meier's F-15 Strike Eagle. The firm's unsuccessful foray into the arcades sunk MicroProse into a hole of debt it couldn't dig out of, ultimately leading to a desperate IPO for cash. It still wasn't enough to stop the bleeding; in a last attempt to save the company, Stealey arranged the sale of MicroProse to Spectrum Holobyte, a rival game developer, in 1993. But surprise, surprise: Sid Meier was already clear of the sinking ship and swimming free, with Bruce Shelley not too far behind.

Sid Meier's Civilization lives on in three highly successful sequels -- Civilization II through IV -- and in the hearts and minds of millions of players whose lives have been touched, or perhaps grasped, by Meier's addictive magnum opus. Meier joined Firaxis Games (founded by fellow MicroProse alum Jeff Briggs), after the collapse and reorganization of his former company. He continues to produce fun and innovative computer games, including recent 3D remakes of Sid Meier's Pirates! and Sid Meier's Railroad Tycoon.

Bruce Shelley found success with Ensemble Studios, a new game design firm he joined after leaving MicroProse. Ensemble is currently best known for Shelley's Civilization-inspired Age of Empires series, which has been a phenomenal success in its own right. "Working on Civilization particularly, and working with Sid in general, was the opportunity of a lifetime. It has opened doors and led to other opportunities, and for that, I will always be grateful," remarks Shelley, unmistakably proud of his role in computer game history.

As for Meier, he's comfortable with a legacy inextricably tied to Civilization: "I think that if that's what's on my epitaph, 'Did Civilization,' that would be fine." In musing about the fate of his beloved series, Meier finds himself satisfied with what the future might hold for the franchise: "There’s probably somebody getting ready for their first day of college that’s probably going to be a part of Civilization in ten to fifteen years from now. I think it’ll be around for quite a while."

What was the first computer you ever used?

Sid Meier: Well, that would be in college, I guess. It was an IBM 360 mainframe. We would submit batch jobs to the mainframe and learn how to do FORTRAN programming. That would have been in the early '70s.

What was the first personal computer you ever used?

Sid: The first personal computer I had was an Atari 800. 16K of memory.

Do you remember the first computer game you ever played?

Sid: An arcade "Pong" game would probably have been the first computer game.

Did you every play anything like Hunt the Wumpus on mainframes back in the day?

Sid: I'm trying to remember. I actually wrote games. I did a "Star Trek" space game, and I believe a tic‑tac‑toe game. I was fooling around with games even when I was supposed to be doing real work, back in the early mainframe days.

What was the first computer game you ever created for personal computers?

Sid: When I got my 800, probably the first game I wrote was very similar to Space Invaders. It had little creatures coming down and you shot them from the bottom of the screen. It was written in assembly language. I didn't have a disk drive, so I saved it on a cassette tape, and I had to hand‑assemble it in assembly language.

Did it ever get distributed or published anywhere?

Sid: I think I sold maybe five copies. I took it to my local computer store and they had very little software for sale. I put it on a cassette tape and into a plastic bag. I remember they bought five or ten copies of it.

What did you call it?

Sid: That's a good question. I don't remember the name of it, but it would have been "Alien Invasion," or something like that.

What was your first game that was widely published and distributed?

What was your first game that was widely published and distributed?

Sid: Shortly thereafter, Bill Stealey and I started MicroProse Software, and the first game that I wrote was called Chopper Rescue. It was sort of a side‑scroller. You had this helicopter, you had to rescue these people and, of course, people are shooting at you all the time. That was the first game I published. It was for the Atari 800.

I believe I've played it; I'm a big fan of the 800. Did you ever play M.U.L.E.?

Sid: Yeah, I played M.U.L.E., Seven Cities of Gold, Archon, the early Chris Crawford games like Eastern Front and that nuclear power game. I played a lot of the early games. Jawbreaker -- remember that one? That was a Pac‑Man type game.

I remember it well. Do you think playing those Atari 800 games had any sizable influence on you as a game designer later on?

Sid: I think they were all fun to play. And we'd always look at the technology and say, "Well, how are they doing that?" and "How can we use that? How'd they get that to do those graphics?" So we were learning the technology, because that was one of the big limitations, the technology. I was always interested less in the arcade style games and more the strategy type of stuff. It was fun to play the games and see what you could do with the technology, but we tended to go in our own direction in terms of game design, I think.

When did you first get the idea to create Civilization?

Sid: I think a couple of things led to the original idea for Civilization. The game I had done before Civilization was Railroad Tycoon. It was the first game that I had done that was more of what now falls into the "god game" genre -- less about flying an airplane, or a tank, or submarine, and more creative: you know, create something and take a map and make something of your own. So that was part of the inspiration.

That was a fun game to make and I was looking for an even more interesting topic to do a "god" type of game. I had played quite a bit of SimCity at the time. And again, it was a really good example of how it was fun to build something. I think the board game, Risk, that I played when I was a kid was a little bit of an inspiration there. You know, conquering the world.

I can see that.

Sid: So those things stirred together. There was actually a board game, a Civilization board game, but I hadn't really played that. It had a different approach. [My Civilization] was kind of like Risk brought to life on the computer. That was the original idea. And then when we added the technology and the whole sense of history to it. Putting all that together was the inspiration for Civilization.

So it just took on a life of its own once you started rolling.

Sid: Yeah, it did. A lot of the pieces fell together nicely. I think we were really impressed with Railroad Tycoon, how you could have a game that included an economic component -- actually building something, actually operating the trains, and some competition with other rail barons. We were ready to try a game that combined a lot of different pieces in an interesting way: the diplomacy, the economics, the military, and the building. Putting all that together was, I think, really where the fun of Civilization appeared. You were doing all these different things, and you felt you were this great leader.

I've heard of that "Civilization" board game by Francis Tresham. So you hadn't played that before? Or had you just briefly played it?

Sid: I had not played that before I did Civilization; I played it later. I remember there were some cards and trading. It was more ancient; it didn't really come into any sort of modern or medieval times. It was more of an ancient kind of game.

It's interesting because Tresham also created 1829, a railroad board game. We played the American version of it, 1830, before we did Railroad Tycoon. So there's definitely a connection in terms of the topics between board games and computer games. But the inspiration for Civilization was more SimCity, our railroad game, and Risk. Most kids play Risk when they're young, and the idea of conquering the world is pretty satisfying.

Did Tresham know that you were making a computer game called Civilization at the time?

Sid: Not that I know of. We didn't know the game was going to be called Civilization when we started it. As it came together, it just felt like the right name. We actually dealt with Avalon Hill, which owned the rights to that name in the United States, because they published the board game. So we didn't deal with Frances Tresham, or anyone in England. We dealt directly with Avalon Hill in terms of getting the rights to the name and things like that.

So MicroProse didn't have any legal trouble because of that?

Sid: No, we dealt with Avalon Hill. They owned the American license to it. And there were no legal issues. I know that, later on, there were some strange legal things that went on between Activision and...other things like that, but that was later.

It was out of your hands; it's the business people doing that stuff.

Sid: [laughs] Right.

Before we get off the Tresham / board game thing -- I read something on Wikipedia, the tome of all correct information (I'm saying that sarcastically, of course), that there was some kind of flier for the board game distributed in the box of your Civilization. Is that true?

Sid: I'm not aware of that. I wouldn't be surprised if there were some arrangement with Avalon Hill that we would put something in our computer game about their board game, and they would put something in their board game about our computer game. It's not unusual, but I would imagine that would have been done with Avalon Hill; I'm not specifically aware of it.

How old were you when you developed the first Civilization?

Sid: I was...let me do the math here. This was '89, so I would have been 35.

Can you give a little window in to what your life was like at the time, in general?

Sid: Sure. I was having a wonderful time as a game designer at MicroProse, my dream job. I mean, it was really what I enjoyed and loved doing -- still love doing. I was married at the time. My son was born in 1990, so he was on his way at the time. I was living in the Baltimore area, working at MicroProse just having a great time making games. Nothing really too unusual.

MicroProse had been in business for eight or nine years at that time. And we had assembled a pretty good group of designers, programmers, and artists. That kind of represented the golden years of MicroProse, where we had some good games and we really felt we could tackle new topics and give new things a try. So it was a great creative time, I think, in the industry and also at MicroProse.

You must look back on the era fondly.

Sid: Yes. It's always fun to make computer games, but I think in those days we really hadn't come up with the idea of a genre yet, so we would say, "Let's do a game about pirates!" "OK! There will be sword fighting and there will be ships!" or "Let's do a game about civilization." "Yeah! We'll have economics and diplomacy. There will be military..." We didn't say, "What category are we going to fit this into?" There was a lot more experimenting. The graphics and the sound technology were limited, so the investment wasn't so high to make a game.

You could only make it look so good, or sound so good. So we didn't have to spend the millions and millions and millions of dollars like we do today. It was a little less risky, so we could take a chance with games because they didn't cost as much money. That was fun; It was exciting.

It was more "anything goes" instead of having to fit into "first person shooters" or "real‑time strategy games."

Sid: Right. We just started with the topic, as opposed to the genre. We said, "Pirates!," or "Railroads!," or "Civilization," or "Civil War," or whatever. It was like, "It's a neat idea. Now what do we do to make it fun?" That's basically what we started with.

What computer platform was the first Civilization originally designed for?

Sid: It was created on the IBM PC. I remember discovering -- this is esoteric -- but I remember discovering a way to do overlays. At the time, a PC was limited to 640K of memory. I found this way to do overlays where we could bring in extra code from the disk to replace code that was already there.

So we could do all these reports like that by just bringing stuff in that you didn't need all the time. It opened up new possibilities -- allowed us to make the game, add more code to it, and do more stuff with it. And we were also transitioning from 16‑color EGA graphics to 256‑color VGA graphics, which were awesome! [Civilization] actually supported both EGA and VGA. That's really where the 16-civilization limitation came from, because we only had 16 colors from EGA. [laughs] It was definitely an IBM PC product to start with.

How much of the coding did you do on Civilization personally?

Sid: I did just about all the coding. I had some help with some tools and things like that. But I'd have to say that I did most of the coding in that game. And some of the art.

Did you draw the little settlers and things like that?

Sid: I did versions at the beginning. I'm not sure how many of them survived until the end. I think some of the original units were more mine, at least in the EGA version.

How much involvement did you have with ports of Civilization to other platforms like the Amiga or the Mac?

Sid: Not a whole lot. We would supply the source, the original code, but often that was contracted. I know there were some versions done on Japanese consoles that were very strange. We had some involvement, but it wasn't direct involvement.

I actually have a version of Civilization for the Super Nintendo. It's pretty decent. Have you ever played that one?

Sid: I remember a version where this angel character comes up at the beginning and explains like, "Long ago, far away, this and that."

Yes, that's it, I think.

Sid: That's it?

It's really Japanese‑ish.

Sid: Yeah, I was just, you know, blown away. [laughs] So I never went much further than that. But I'm happy to hear it was a good version.

Did you ever play the other versions, and did they ever disappoint you?

Sid: Not a whole lot. I didn't spend a whole lot of time with the other versions.

Sid: Not a whole lot. I didn't spend a whole lot of time with the other versions.

I guess you always had your definitive PC version.

Sid: Yeah, I thought of the PC version as the definitive version. I'd spent a year and a half, or whatever, with it, so I was probably ready to move on to something else.

When you were creating Civilization, how much research did you put into world history?

Sid: Not a whole lot. I did do a little bit of reading, and it's kind of where the idea of the city as one of the kind of core elements of the game came from. It just struck immediately: "4000 BC the first city was formed," and I thought, "Oh, that's a cool place to start the game." But basically, I tried to use fairly well‑known concepts, well‑known leaders, and well‑known technologies. I mean, it wasn't intended to be "bizarre facts about history." It's more like, "Here, we all know a little bit about history, but now you get to take control of it, invent gunpowder, and the wheel, electricity, all sorts of cool stuff." But you don't have to research to know what it is, you just know.

So you mostly based it off your personal knowledge and education?

Sid: Right, it was intended to be something that anybody could play. It didn't require a Ph.D. in history to be able to pick it up and play it.

Did you use any specific sources to check any of your information? Encyclopedias or certain books?

Sid: I had a couple of "timeline of history" type of books, so if I wondered when the printing press was invented, or whatever, or to check to make sure we weren't too far off or how to spell a particular leader's name. We had few references like that. But it was not, there wasn't a whole lot of...

So there was no intensive effort to make the game extremely accurate?

Sid: Right, because the idea of the game is that you can change history. So we're not trying to recreate history exactly. Now Bruce Shelley, who I worked with on the project, did some research in writing the Civilopedia and the manual. He did a lot of research to get the real facts in there. That was not part of the actual game design.

Bruce Shelley collaborated with you on Civilization. How big of a role did he play in the game's design?

Sid: He was very, very helpful. He was the guy who would play it and we'd talk about what was working and what was not working. And I'd change something, or try something new, and give it to him. He'd play it and say, "Oh, that works," or "That doesn't work." So he was a sounding board; an idea person. He served as a second opinion on everything. We were really collaborating on everything. We worked for months just playing it, and comparing ideas, and coming up with new stuff.

You said he worked on the Civilopedia...

Sid: He created the text for the Civilopedia and wrote the manual.

Would you say that those were his most important contributions to the game? Or just the play testing and feedback?

Sid: I'd say the play testing. The manual and the Civilopedia were done towards the end when we had pretty much firmed up what the game was like. I think the manual was great. In those days, MicroProse manuals were 200 pages, and I think they added a certain special quality to the games. You felt like they were substantial and worth playing.

But I think his contribution earlier on to the game design process was the most helpful: identifying things that were working well, or not, and pointing things out that weren't as much fun.

How did Bruce Shelley get involved in the project?

How did Bruce Shelley get involved in the project?

Sid: The way things worked at MicroProse...I was a programmer/designer, and then I'd work with what would probably be called a producer today -- I'm not sure it was called a "producer" in those days. So Bruce's job was to keep track of how things were going on the project, to be responsible for the manual, and to participate in the design process.

He had worked with me on Railroad Tycoon, which was a particular interest of his. He had actually done the conversion of Francis Tresham's 1829 railroad game and turned it into 1830 for Avalon Hill. He enjoyed railroads. We worked together on Railroad Tycoon, so when we moved on to Civilization, he had just finished a project and he was ready to go. We did Covert Action before. We tended to work together as programmer/designer and producer.

So he was a regular employee of MicroProse?

Sid: Yeah, I'm not sure exactly when he was hired, but he had been there for a couple years. We actually, at that time, had a couple people at MicroProse that had come from Avalon Hill who wanted to move from the board gaming world to the computer gaming world. So there were at least two or three people there that had worked at Avalon Hill, and that was where a lot of design and gaming ideas came from in those days.

Civilization almost seems kind of like an educational Trojan Horse: it's fantastically fun, but it might accidentally teach you something about world history or government systems along the way. Was an educational aspect to Civilization ever your intention at all?

Sid: No, not really, we distinguished between education and learning. The intent was never really to educate people, but we do think that part of the fun of playing a game is some element of learning. Even if you are playing a first person shooter, you learn where the good places to hide or what weapons are good. Part of the fun is learning something; feeling that "I'm better at this game than I was yesterday, and if I play a little more I'm going to get even better."

With Civilization, the things that you're learning about are history, different technologies, how government works, the importance of exploration, and things that are historical. We really think that learning adds to the fun of a game. Civilization provides enough interesting decisions that you have to think about; you try things out, and I think that makes the game more fun.

I read an interesting article recently about how some teachers actually use Civilization III in their classes as a teaching tool. Would you endorse or recommend the use of Civilization III as an educational product?

Sid: There's certainly nothing in the game that's just totally, flat-out wrong. I think Civilization is a good place to learn some basic ideas about history, and to be a part of it; to make the decisions. The great thing about a game is that you're the star of it. You're actually there making the decisions. Yes, it's been used in a lot of different educational situations, and if you can get a kid interested in history through a game, that's...We certainly lead them through the Civilopedia. We let them know that there's more out there if you want to explore it.

I've heard about a lot of people who played games as a kid and have gained a lot of useful knowledge that they were able to use later in life. So I certainly encourage people to use Civilization as a way to introduce them to history and make it exciting.

Have you ever heard from any political or world leaders that might be fans of Civilization?

Sid: [laughs] Not any world leaders, no. I remember getting a call from the Wall Street Journal a couple of years back, and they where fascinated about how Civilization illustrated taxation policy, something I had no... It's amazing what people read into the game. So I think it's great; people play the game and get involved with it, and people start to imagine and find all this stuff in the game that they find interesting.

Speaking of reading things into it, I've read some criticism of Civilization that accuses the game of being Western-centric, or American biased. What do you think about that?

Sid: I think that's probably true. In those days, there was a little bit of a Cold War mentality about the game. The world was divided between the West and the Communist worlds, and we were trying to present the most familiar leaders, the most familiar technologies, and the most familiar ideas. And the game-playing world was much more an American world in those days; today it's much more of a global audience. PC games were played mostly in Western countries. So I think Civilization had somewhat of a Western-centric view of the world. Just the whole idea that technology drives progress might not be so much of an Eastern concept as it is a Western one, so I think it's true.

Have you tried to address some of those concerns with newer versions of Civilization, like with Civilization III?

Sid: We have. There have been a couple directions we've gone with the later versions of Civilization. One of the criticisms was that the game was too militaristic, that it was basically a military game. We tried to create different victory conditions, but the military aspect of the game was in many ways the most interesting and the most fun to play. So it often become a military game, which, I think, is not necessarily a bad thing.

But in later Civilizations, we tried to flesh out, and make more interesting, some of the other victory paths. We tried to include more female leaders in later games. We tried to include more third world, Eastern, or less familiar leaders in other games, and to include more civilizations from around the world. We did include a bigger variety of civilizations and peoples as we expanded it.

Civilization is known for its addictiveness: it's commonly called the "one more turn" phenomenon, as I'm sure you know. Do you know where the phrase "one more turn" originated?

Sid: I would guess from a magazine review. But I don't specifically remember when I first heard that term, or where it came from. Civilization did have that special quality of giving you something to look forward to. There's always one or two things you're looking forward to, like when that building is done, or when I get that new unit, or finish that technology. So there was never really a good place to stop playing.

Have you ever become addicted to playing Civilization yourself?

Sid: [laughs] I've often found myself playing and then realized I'm late for a meeting, or forgot this or that. So yeah, I've been exposed to the phenomenon myself.

Could you put into your own words why Civilization has incredible replay value and long-term appeal?

Sid: There are a lot of elements of the game that lend themselves to replayability, like the sixteen different civilizations, the different starting places, or the fact that the map is random each time. Every game is going to be different. The different paths to victory. The decisions you have to make along the way. You often have to choose between, "Do I build a new unit, or do I make this building?" There are all sorts of reasons to come back and say, "Well I want to try this other path the next time." The fact that there are so many different ways to play, and that they all seem interesting and fun, leads you to want to play again after you finish the game. I think that leads to the long-term replay value.

Civilization III improved upon Civilization II with more units and new ways to win. And Civilization IV seems to have expanded on that even more. Do you think you can keep improving Civilization sequels without making them unplayably complicated?

Sid: That's something that we are aware of. With Civilization IV, we tried to take something out with every new thing we put in. We felt we where bumping up against the limit of complexity for Civilization game players. We have new ideas, but we take the general approach that for every new thing we put in, or more complicated thing we put in, we either simplify or take out something that was in there before. It's a very rich topic; we could put so much stuff in there that we could overwhelm the player. We are sensitive to that.

If you could change one thing about the original Civilization, what would it be?

Sid: Zones of control, I'll say. There were a number of ideas there that I thought were necessarily but added more complexity than play value. Some ideas like zones of control and maintenance cost, and things like that. Looking at it today, I might try to streamline the game a little bit more and make the rules not quite as detailed or obscure than some of them were in the original game. Overall, I'm very happy with the original design, but there's always a few things you would do.

Do you play the original game anymore?

Sid: It's been a long time since I played the original game, but I have fond memories of it. I remember playing when I was developing it, and I remember it being a lot of fun to play.

Do you ever feel that the success of Civilization has overshadowed your other games?

Sid: Well, no. Frankly, Civilization has, in many ways, allowed me to do my other games. So I have no complaints at all about Civilization. I think that if somebody likes Civilization, they may be more likely to consider Pirates, or another kind of game that I've done.

Especially when your name is written on them. That helps.

Sid: Right. And if Civilization is the best known game I make, then I'm perfectly happy. It's a game that I'm really proud of.

Which game are you more proud of: Civilization or Pirates?

Sid: Oh...that's like asking, "Which of your children do you like the best?" [laughs]

I think Civilization was maybe a more complete game, but there are a lot of cool things about Pirates as well. Civilization, I'd have to say, is probably still the game that has the most cool ideas in it.

It's your landmark game.

Sid: Yeah, I think it just struck a chord with game players. We made some good decisions and it came out at a good time. We do still get a lot of people who remember it, who still play it and enjoy it.

Have you heard of the open source clone of Civilization called FreeCiv?

Sid: I have heard of it. I don't know much about it at all.

You've never played it?

Sid: I have not played it, no.

Do you purposely avoid it, just because...

Sid: No. There are so many good games out there, and I've played the original Civilization plenty, and I still like Civilization in general. I still have ideas, and we're still working with new stuff, but the first game was a while ago, and we're looking more forward than back.

Do you find it flattering or more annoying that they cloned it?

Sid: No, I find it flattering. To see the forums, Apolyton, places like that. To see people doing stuff with it: keeping it alive and really putting their energy into playing it, maintaining it, coming out with mods; all the stuff out there. I think that's great. The whole community aspect of it really keeps it alive. The community can do so much more than we can on our own. We try to plant the seed and provide the tools and let people do great things with it.

Each version of Civilization, from one through four, seems like it has its own distinct character and charm. The sequels add new features but don't obsolete the earlier games. They're all still playable. So the question is: which version of Civilization is your favorite: I, II, III, or IV?

Sid: [laughs] Well, they all have something special. Civilization I is my sentimental favorite, because that was the first one. And we were really charting brand new territory. I think Civilization IV is a great version. There's a lot of cool new stuff, a great interface, and multi-player support -- the best it's ever been. And there are some new ideas with religion and things like that. So I'd have to say Civilization I and Civilization IV are my top favorites.

Did you have any direct involvement with Civilization II?

Sid: Civilization II was primarily Brian Reynolds' design. We talked about ideas, and I played it, but that was mostly his design. I was there; I was available, and I played. But primarily, he was the main designer behind that.

Did you like how Civilization II turned out?

Sid: Yes, I think it turned out very well. It fixed a few things that were not working right in Civilization I, and it really expanded the game. We were a little hesitant to make the original too big, and I think Civilization II said, "OK. You know how to play Civilization. Now let's give you more units, more technologies, and more stuff to do." So, it was a natural evolution from the first game. I think if we'd brought it out first, it would've been too much; but once people got used to playing it, Civilization II was the right game at the right time.

What's the earliest year in which you've blasted off to Alpha Centauri?

Sid: [laughs] I actually don't play so much for the most awesome victory, or the most, you know. I'm often intrigued by, "What would happen if I do this?" or "I probably shouldn't do this, but what would happen if I tried this?" So I generally don't play for points, or score, or quickest victory. I try to get more into the experience and say, "How can I make this whole game play experience more interesting?" by trying something that I haven't tried before. I don't keep track of those kind of statistics.

So you don't keep your high score etched on a desk somewhere? "800 BC." [laughs]

Sid: No...I know it's just a number that I could patch, so it doesn't mean a lot to me. It would be too easy to cheat. [laughs]

Could you sum up why you think Civilization has been continuously popular for the last sixteen years?

Sid: Well, I think Civilization is based upon some good, sound, fundamental game design principles: giving the player some very interesting things to do and immersing them in a world that is kind of familiar, but also has lots of possibilities. And even though the technology has evolved tremendously over the last 15 years, those kinds of core game play elements, I think, stand the test of time.

Finally, is there anything else you'd like history to know about Civilization that we haven't covered? Any misconceptions or rumors that you would like to put to rest?

Sid: No, I'd just like to reiterate that it's been a great experience for me. Civilization is a game I'm very proud of, and I'm very happy to have been a part of it. I appreciate all the game players who've played it, sent us their great ideas, and have been part of making it a success.

1957, Risk, the board game created by Albert Lamorisse, was first released as La Conquête du Monde ("The Conquest of the World"), in France.

1959, Parker Brothers publishes Risk in the United States for the first time.

ca. 1973, Students at Evergreen State College in Olympia, Washington program a computer game titled Civilization (later popularly known as Empire) for an HP2000C mainframe computer, based mostly on Risk.

1980, Hartland Trefoil publishes Civilization, a strategy board game designed by Francis Tresham, in Britain.

1981, Avalon Hill publishes Civilization, the Hartland Trefoil board game, in the United States.

1982, Sid Meier and Bill Stealey found MicroProse Software.

1984, Avalon Hill publishes Incunabula, a computer game based on their Civilization board game, for MS-DOS computers.

1989, Broderbund publishes SimCity, designed by Will Wright and developed by Maxis.

1989, Electronic Arts publishes Populous, designed by Peter Molyneux and developed by Bullfrog.

1990, MicroProse publishes Sid Meier's Railroad Tycoon.

1990, MicroProse publishes Sid Meier's Covert Action.

1991, MicroProse publishes Sid Meier's Civilization.

1993, Spectrum Holobyte purchases MicroProse Software, Inc.

1995, Avalon Hill publishes Advanced Civilization, an official computer version of the Hartland Trefoil Civilization board game.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like