Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Gamasutra presents part three in contributor Matt Barton's extensive look at the history of computer role-playing games, this time exploring the years from 1994 to 2004. <a href=http://www.gamasutra.com/features/20070223a/barton_01.shtml>Part one</a>, covering 1980-1983, and <a href=http://www.gamasutra.com/features/20070223b/barton_01.shtml>part two</a>, covering 1985-1993, are also available.

Welcome back, brave adventurer, to the third and final installment of my history of our favorite computer game genre--the Computer Role-Playing Game, or CRPG for short. If you are new to this series, I'd suggest you stop now and read The Early Years, which covers the dark origins of the genre, such as Richard Garriott's Akalabeth and Sir-Tech's Wizardry series, and of course early mainframe CRPGs like dnd. You should then check out The Golden Age, which picks up from 1983 and extends all the way to 1993, a period which represents the peak of CRPG development.

Hundreds of games and dozens of series appeared during this time, several of which extend into the Platinum and Modern Ages. The Golden Age includes classics like SSI's Pool of Radiance (1988) and Phantasie (1985), or Interplay's The Bard's Tale (1985) and Wasteland (1988), and plenty of highly innovative titles like Sierra's Hero's Quest (1989) and Masterplay's Star Saga (1987). Without a good grounding in the CRPGs of these earlier periods, you might suffer from the all-too-common delusion that recent games like Diablo, Neverwinter Nights, and Oblivion came out of nowhere.

“CRPGs are natural extensions of their traditional pen-and-paper games or table-top miniatures. Instead of simply imagining monsters and moss-covered labyrinths, computer games burst with ethereal life, thanks to ever-evolving graphics and sound effects. Hard-liners may complain that the real magic has been lost; for the rest of us, however, CRPGs are the realization of our dreams - or more often, our nightmares.”

–Scott A. May in Compute!, Jan. 1994.

Instead, these games can all trace their lineage back to Golden Age games, which can in turn trace their lineage back to the late 1970s. Indeed, although it's a commonplace in game history to blurt out things like, "We've sure have come a long way since Akalabeth!", at one level we really haven't taken more than a few timid steps.

Sure, there have been enormous changes in graphics, sound, interface, and so on, but much of what we cherish in a modern CRPG was already present in games like DynaMicro's Dungeons of Daggorath and Texas Instruments' Tunnels of Doom (both 1982). Furthermore, many games that come fairly late in the time line actually seem to some critics to be steps backwards. For instance, although FTL introduced Dungeon Master in 1987, which featured real-time, 3-D graphics in full color, other developers continued to release best-selling turn-based and tile-based games well into the 1990s. And even in 2007, many critics argue that ASCII or ANSI games like Rogue have never been surpassed, since snazzy graphics and intricate story lines just distract from what they think makes CRPGs fun to play.

In short, rather than view the history of CRPGs as a neat time line that begins with total crap and just keeps getting less crappy all the time, I see it as a treasure-filled, monster-infested dungeon. While you can get from one point on that path to any other, you'll never travel in a straight line--and you never know what's waiting for you around the next corner. Let's just hope you brought your loquacious old pal Lilarcor!

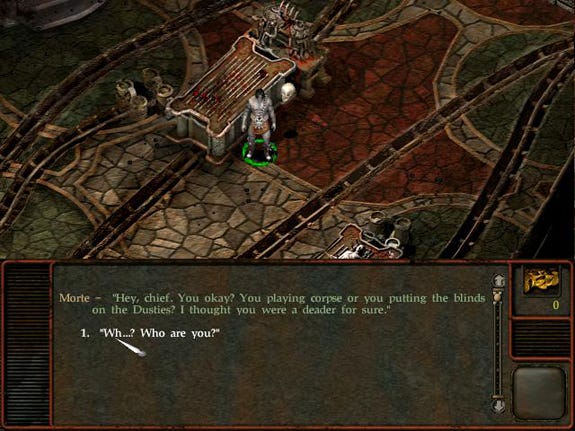

To my mind, the games that really represent the best of the genre appeared during the period I've termed the "Platinum Age," which begins in 1996 with the publication of three very important games, Origin's Ultima Underworld: The Stygian Abyss (1992), Blizzard's Diablo, and Bethesda's Elder Scrolls: Daggerfall (both 1996). Other high points of the age include Interplay's Fallout (1997), Black Isle’s Planescape: Torment (1999), BioWare's Baldur's Gate (1998) and Baldur's Gate II (2000), Troika's Arcanum (2001) and Sir-Tech's Wizardy 8 (2001).

The single-player, standalone CRPG reached its zenith during this period, and I've begun to doubt if Baldur's Gate II will ever be surpassed. Even in many of these games, though, the presence of online, multi-player options signaled the impending doom of the old CRPG we knew and loved. At the end of the platinum age, the Massively Multiplayer Online Role-Playing Game, or the MMORPG, dominated the scene, and, at least to this critic, the future of the CRPG is grimmer than anything ever dreamed up by Lord British.

BioWare's Baldur's Gate single-handedly brought AD&D back to the masses.

Not all that glitters is platinum, however. It’s during the early 1990s that we really begin to see games marred by sloppy code, particularly on the DOS and Windows platforms. Many otherwise impressive games were doomed at the start by hundreds of game-crashing glitches, which infuriated gamers and united critics against them.

The likeliest explanation for the preponderance of bugs during this era is an industry-wide shift in development methods. Instead of just a handful or even a single person in charge of the coding, games were being built by increasingly large teams of specialized programmers, who would work on individual parts and then jam everything together. While this process occasionally went smoothly, more often that not bits of the code were incompatible, and finding bugs in such massive piles of code was like finding the proverbial unassigned pointer in the memory stack.

Another key issue was the lack of industry standards among early graphic and sound card manufacturers; developers had to slap together code to support dozens of different standards—or risk alienating hordes of money-waving gamers. While it's now relatively easy to download and install a patch to address such issues, most people weren't online until well after many of these bug-infested games had passed out of circulation.

The period I've termed the "Modern Age" begins in 2002 with the publication of BioWare's Neverwinter Nights, and includes games like Microsoft's Dungeon Siege and Troika's The Temple of Elemental Evil. Although these games have probably sold many thousands more copies than games from earlier periods, they seem to represent more of a looking back than a looking forward, and I'm increasingly worried by the large number of CRPG fans migrating towards MMORPGs. In fact, I don't even consider these games to be part of the same genre, a point I'll get to towards the end of this article.

Up to now, I've tried to simplify things by postponing my discussion of MUDs (Multi-User Dungeons) and MMORPGs (Massively Multi-player Online Role-Playing Games), which can actually trace their history as far back as the stand-alone CRPG. I'll explain why at the end of this article.

Let's pick up our story, then, in 1992, a year which culminated in Origin's Ultima Underworld: The Stygian Abyss, a progressive game that demonstrated new and exciting possibilities and would set the tone for much of what would follow.

The early 1990s saw the publication of dozens of CRPGs from many different developers, many of whom are virtually unknown today. Although the DOS and later Windows platforms would soon dominate the computer game industry, for now both the Atari ST and Commodore Amiga were going strong.

Although highly polished, many of the CRPGs developed during this time are highly derivative and offer little innovation, but a few have managed to attain cult classic status.

“A thousand years ago, tucked deep in the beautiful woods to the southeast of Lyramion, there was a small village called Forkbrook. The people who lived there were blond haired and good natured; they lived by fishing and hunting and traded with the nearest town which lay two days travel to the west. In this village lived a small boy named Tar.”

– from the Amberstar manual.

Several of these early 1990s games were German imports. One such game, Amberstar by German developer Thalion, features good graphics, a great auto-mapping tool, and a huge world to explore. It seemed to offer much promise, but even a well-known soundtrack by chipmaestro Jochen Hippel was not enough to win it much fame in the US. The sequel, Ambermoon, was only released in Germany, and the third game (the series was planned as a trilogy) was never completed. Nevertheless, Amberstar is among the best CRPGs for the Amiga platform.

In 1992, Sir-Tech published an English translation of Realms of Arkania: Blade of Destiny, another successful German game based on the RPG system Das Schwarze Auge (The Dark Eye). The Dark Eye system was a strong competitor for Dungeons & Dragons in Germany, and offered gamers a viable alternative to TSR's rules. One nice innovation is that characters suffer from a variety of negative attributes, such as fear of the dead or a hot temper, which have direct effects on gameplay.

The game sold well enough to warrant two sequels, Star Trail (1994) and Shadows Over Riva (1996), both of which were only available on the DOS platform (the first was available on the Amiga and Atari ST platforms). The last game took advantage of the by-then widely adopted CD-ROM, and boasted SVGA graphics, but all of the games switch between 3-D, first-person perspective in exploration mode and isometric view in combat mode ("isometric view" or "3/4 perspective" is a way of portraying a 3-D object on a flat surface; consider the familiar line drawing of a cube). The combat system is highly tactical and turn-based (reminiscent of an SSI Goldbox game). Of the three, most critics agree that Shadows over Riva is the most excellent, and I'll have more to say about it later.

Other interesting games of the early 1990s are Imagitec's Daemonsgate, Microprose's Darklands, and Flair's Whale's Voyage. Daemonsgate (1992) seems to be an exercise in poor design, and is only noteworthy for its unusual marketing gimmicks. It suffered from a ghastly interface, and its most noteworthy characteristic is that it shipped with a VHS tape. The tape contained a goofy video entitled "Travis Sewerbreath" that had only a tenuous connection to the game. Daemonsgate also featured a "conversation system" allegedly capable of understanding over 70,000 words (few critics seem to believe this blurb on the game's box).

If Daemonsgate is all hype and no substance, Darklands, a meticulously historical CRPG set in medieval Germany, is all substance without enough hype. Indeed, it is undeservedly obscure despite its mind-boggling attention to detail. For instance, not only does the game include historically accurate arms and armor, but even the weights and relative effectiveness are incorporated into the gameplay. It also boasts of a huge gameworld with over 90 German cities and towns, all with historically accurate place names.

The goal of the game is simply to win fame and fortune; the game is quite open-ended and avoids many of the stale D&D clichés. Magic, for instance, is based on the ancient art of alchemy and is quite intricate, and clerics can call on 140 different saints, each with a unique personality.

Many gamers appreciated its intelligent character generation system, which involved adding years on to the character's starting age in return for valuable skills. Unfortunately, the game's code was riddled with show-stopping bugs, and gamers found the save game system irritating at best. Nevertheless, it remains a cult classic with a small but highly dedicated following.

Darklands is the most historically accurate and detailed CRPG yet designed.

Whale's Voyage is perhaps best described as a combination of Firebird's epic space-trading game Elite and SSI's Eye of the Beholder, and vaguely reminiscent of Binary System's earlier and much more successful Starflight series (1986, 1989) and Electronic Art's Sentinel Worlds (1989). Whale's Voyage did not fare well among critics, many of whom bashed it for its cumbersome control scheme, which required dozens of mouse clicks just to get one of the player's four characters to attack.

The game does feature a unique character generation method involving eugenics and DNA manipulation. After choosing an appropriate set of parents, players can "mutate" their characters' DNA in exchange for better stats. The trade-off, however, is greater susceptibility to disease. Players also get to choose which schools and universities their characters attend. In any case, the game was not a hit, and although there was a sequel released in Germany, an English version never arrived on American shores.

While we're on the subject of rotten tomatoes, we should probably mention Cybertech's Spelljammer: Pirates of Realmspace, which almost certainly contributed to its publisher SSI's fall from grace. Although TSR's Spelljammer universe was successful among tabletop role-playing gamers, Cybertech's effort to bring the world to DOS failed just as miserably at Cybertech's, and for much the same reason. Besides lackluster graphics and the lack of a good plot, the game was not properly play-tested and frustrated gamers with bug-infested code.

We saw in the last installment how FTL's Dungeon Master represented a significant breakthrough for 3D CRPGs. Although there had been plenty of other 3D, first-person perspective CRPGs before (including the real-time game Dungeons of Daggorath), turn-based games were by far the majority. However, even though Dungeon Master was the best-selling game of all-time for the Atari ST platform, and achieved remarkable success on other platforms like the Commodore Amiga, many gamers and developers seemed reluctant to jump on the real-time 3-D bandwagon.

The first big developer to do so in major way was Westwood Associates, who developed an extremely successful series called The Eye of the Beholder, published by SSI (their so-called "Black Box" games). However, although these games were set in real-time, movement was not fluid but discrete. For instance, if your party turned left, the perspective instantly shifted 90 degrees, cutting rather than panning to the new viewpoint.

Nevertheless, many Dungeon Master clones were published in the early 1990s, such as Raven's Black Crypt, ArtGame's Abandoned Places: A Time for Heroes, and Silmaris' Ishar: Legend of the Fortress (all 1992), a highly-polished game that was successful enough to spawn two sequels (Messengers of Doom in 1993 and The Seven Gates of Infinity in 1994).

Another popular game from this period is Virgin Games' Lands of Lore: The Throne of Chaos, developed by Westwood Studio--the same company that produced Eye of the Beholder. Throne of Chaos was noted for its excellent graphics, music, and interface; Westwood was an experienced CRPG maker at the height of their game. Westwood developed two sequels, Guardians of Destiny (1997) and Lands of Lore III (1999), which we'll discuss later.

Cute, vibrant graphics and humor distinguish the Lands of Lore series from most CRPGs of its day.

Origin's Ultima Underworld: The Stygian Abyss was the first 3D CRPG to finally achieve fluid camera movement (and is said to have inspired id's famous first-person shooter engine). Developed by Blue Sky Productions (later Looking Glass Technologies), The Stygian Abyss is a spin-off of Origin's celebrated Ultima series, but its gameplay focuses more on quick physical reflexes than its predecessors.

On the surface, it seems like Origin's attempt to mimic Dungeon Master. It's set deep in a dungeon, and the Avatar needs to constantly search for food and light sources (e.g., torches). Even the magic system is similar; spells are cast by arranging sequences of "rune stones" found sprinkled throughout the dungeon. However, unlike Dungeon Master, Ultima Underworld features fluid 3-D movement. Players can not only turn left and right smoothly, but also look up and down, climb up, and even swim.

Players also have more direct control during combat: The type of attack (slash, stab, hack) is indicated by the position of the mouse pointer, and the strength by how long the player holds down the mouse button. Many gamers and critics argued that these innovations made the game realistic and thus more immersive, as though players were actually in the game rather than simply controlling it from a distance.

Another nice feature was a "map," which not only tracked movement but allowed players to enter notes. In any case, you don't have to be a game historian to see how this game paved the way for the Elder Scrolls series.

The Underworld series was ahead of its time, but that's not always a good thing. How much immersion does it take to kill rats with a hatchet?

The storyline is fairly straightforward. Somehow, the Avatar has found himself back in Britannia just in time to witness a creature carting off a Baron's daughter in a sack. Naturally enough, the guards suspect the Avatar of being an accomplice. Fortunately, he's spared the noose, but only on the condition that he enter a fearsome dungeon called the "Great Stygian Abyss", and return with the Baron's daughter.

Soon enough, the Avatar encounters some survivors of a failed colony, and eventually learns that the kidnapping is only part of a much more sinister plot. It's a good storyline that makes the game more than just a 3D coding feat.

In designing the Underworld system, one of the things we attempted to do was to merge traditional fantasy RPG elements, such as quests and combats and explorations, with a sophisticated three-dimensional simulation of a sensible and believable world.

– from the Ultima Underworld II manual.

Origin followed up in 1993 with a sequel named Labyrinth of Worlds. The sequel made few innovations other than the implementation of digital sound effects and an expanded viewing area. The storyline is also more complex and more closely related to the main Ultima series. A magical crystal of "blackrock" has formed over Lord British's castle, isolating the land of Britannia from its foremost defenders. Fortunately, the Avatar can use a smaller crystal to travel to eight different dimensions in search of a solution to the dilemma. It's a massive game, and the alternate dimensions allow for many intriguing scenarios, such as a fortress floating in the sky, an icy wasteland, and a surreal "Ethereal Void."

Surprisingly, the Ultima Underworld series is not as well known today as later games of its type, such as the Elder Scrolls series. Perhaps the key reason for this is that the games demanded more computer power than most PC gamers could afford in 1992. It's a rare case of when a lengthy production delay could have resulted in better sales.

Stygian Abyss was released for Sony's Playstation in 1997 and was ported to Windows Mobile by Zio Interactive in 2002.

We might expect that Origin would have incorporated Ultima Underworld's 3-D engine into its main Ultima series, but this was not the case.

Ultima VII: The Black Gate, released the same year as The Stygian Abyss, featured much better graphics than its predecessors, but still relied on the familiar top-down perspective. Perhaps the biggest interface change was a switch to real-time gameplay, which drastically altered the way combat is handled. It was also the first game in the series that can be controlled entirely by the mouse--the manual indicates that mouse play is "highly recommended by Lord British."

We might not think much of this issue today, but this was at a time when many PC owners didn't even own mice, much less see them as a game device.

Even though Black Gate didn't take the leap into 3D, it is still widely hailed as the best Ultima game, rivaled only by Ultima III in terms of popularity. The key assets are the game's gripping plot, well-developed characters, and painstakingly-detailed environments. Much was made of the game's high level of interactivity. How many CRPGs do you know that will let you milk cows and change a baby's diapers just for the heck of it?

Perhaps the best of all the Ultima Games, The Black Gate sports one of the most fully interactive gameworlds ever presented in a video game .

To put it mildly, The Black Gate is an unforgettable experience to those who have taken 60+ hours required to complete it, and will probably always enjoy a loyal and dedicated fan base. Unfortunately, the original games exploited some memory routines that render them incompatible on modern Windows-based systems. Thankfully, gamers can play Ultima VII using Exult, a GPL-licensed program that attempts to recreate the game on modern operating systems.

The Black Gate's plot is quite sophisticated compared to most games of the era, and like most other Ultima games, it has plenty of references and allusions to religion and politics. As the game opens, the Avatar is taunted by the infamous Guardian, then whisked away to the land of Britannia some 200 years after your visit, just in time to investigate the scene of a ritualistic murder. Eventually he learns about a cult called "The Fellowship," which some critics argue satirizes the Church of Scientology.

Perhaps more endearing than the plot are the characters, who are far better developed here than in almost any other CRPG. Instead of merely standing in one place for all eternity just to offer you a thinly disguised hint or geographical tidbit, the characters are shown walking about, engaging in their daily activities--they even to go to bed at night. Conversations with these characters are also more convincing, and can speak about several topics.

The game is also praised for its open-ended gameplay. There are very few guard rails in The Black Gate, a fact that can either thrill or intimidate inexperienced players. It's quite easy for players to end up wandering about the game without the faintest clue what they're "supposed" to do. Obviously, this lack of clear direction wouldn't bother players weaned on Rogue and other "sandbox" style games, but players more accustomed to "Do X, Y, and then Z" type games may find themselves quite disoriented.

Just to give you some idea of how intriguing the world of Black Gate can be, I'll quote a bit from Oleg Roschin's detailed review of the game on Mobygames. At one point in the game, Roschin's party met up with a unicorn, who, as legend has it, can only communicate with virgins. The first time around, Roschin's Avatar was, in fact, a virgin, and admitted as much to the unicorn, who then talked to him.

On a later visit, however, the Avatar had slept with a harlot at Buccaneer's Den, and the Unicorn refused to speak with him. As usual, we see that Garriott subtlety; sure, you can do sinful things, but you won't always get away with it. Later on, Bethesda would capitalize on this high level of interactivity in its celebrated Elder Scrolls series.

Origin released an expansion for the game called The Forge of Virtue later that year, but it wasn't until 1993 that Serpent Isle appeared. Instead of calling this game Ultima VIII, Origin chose to label it as Ultima VII: Part Two. This odd naming convention seems to arise from Garriott's principle that no two Ultima games should share the same game engine.

Serpent Isle may have shared the same game engine, but was much more linear and story-based than The Black Gate, a fact which divided critics pretty evenly between the two games. The story begins 18 months after the first part, and involves traveling to a land named "Serpent Isle" to restore the balance destroyed there by the Guardian.

Apparently, the game was rushed through production by Origin's new owner, Electronic Arts, and thus contained many dead ends (players who found themselves in one had to restore to earlier saved games). Origin's struggle with Electronic Arts bear an uncanny resemblance to Garriott's earlier conflict with Sierra On-Line. That conflict had also led to a lackluster entry in the series, Ultima II. Origin did release an expansion to the game called Silver Seed in 1993.

On a side note, in 1997 released its Ultima Collection for DOS and Windows, which includes the first 9 games (including a PC port of Akalabeth) and both expansions. Unfortunately, not all of the games run properly in Windows, but with a little work and a tool like DOSBox can run them under emulation.

In 1994, Origin released Ultima VIII: Pagan, a game with a somewhat controversial title that aroused even more controversy among long-term fans of the series. Again, Garriott seems to have returned to the drawing board and decided that what players really needed was more physical than intellectual challenges. Thus, like so many console hits of the day, in Pagan the Avatar can run, jump, and climb across moving platforms.

Combat was reduced (or, enhanced, depending on your perspective) to a series of rapid-fire mouse clicks, requiring more dexterity than strategy to win. As you might expect, the game gravely disappointed some fans and thrilled others, but the general consensus was that the game wasn't up to the Ultima standard. Many of the key innovations that had made The Black Gate so successful, such as a realistic night and day system, were abridged or altogether omitted.

As if these faults weren't enough to commit Pagan to the flames, a plethora of bugs surfaced, frustrating even fanatical Ultima fans. Again, Garriott blamed the problems on Electronic Arts and a rushed production schedule. However, the worst was yet to come.

The last and worst of the single-player Ultima games, Ultima IX: Ascension, was published in 1999, and fans were even more disappointed than they had been with Pagan. The problem this time seems to lie mostly in a bait-and-switch game played by Garriott, who had promised a game more in line with the classic Ultima games, and went to fans for advice—who provided it, diligently. Unfortunately, the production cycle hit gravel early on, and the code went through at least four different versions and no small amount of drama.

Ultima Online was also in production as this time, and no doubt added to the chaos (I'll have more to say about that game in a later section of this article). The end product was a buggy and even more action-oriented game than Pagan, and abandoned the by-then conventional isometric perspective for a fully 3-D world in 3rd-person perspective.

Most Ultima critics bitterly dismissed Ascension out of hand, but the game has managed to attract a small but dedicated fan base. The complaints and defenses are many. One of the most often heard is that it's really more of an "action adventure" than a true CRPG, a claim based on Ascension's rather limited "leveling up" capabilities and rather linear plot structure. Fans of The Black Gate were also irritated by the rigidity of many of the game's events, such as a love story that some felt was "shoved down their throats."

At any rate, no one complained about the game's lush graphics, and the day/night cycle returned, and the music is quite excellent. There is also a high level of interactivity with objects. However, a combination of poor voice acting, lackluster dialog, and rather banal characters certainly haven't helped the game win over diehard Ultima fans, much less large audiences.

Indeed, even a special "Dragon Edition" large-box version of the game that included several trinkets--a nod towards older and more revered Ultima games--wasn't enough to win over jaded fans. Needless to say, Ascension was a sad way for this grand old series to end. It was as if George Lucas had died just after rushing Jar Jar and the Ewoks Save Christmas into theaters.

Even though Ascension failed miserably, German developer Pirahna Bytes was able to follow more successfully in its footsteps, pushing the “action” and “adventure” boundaries even further. The Gothic series debuted in November of 2001, and features a real-time, 3D world set in 3rd-person “over the shoulder” perspective. Gameplay focuses on inventory-based puzzles as well as a difficult arcade-style combat system.

The game is most noted for its dark, realistic ambiance and open-ended gameplay, which seems similar to that found in the Elder Scrolls series but with more focus on character interaction. Despite some irritating interface problems and bugs, the game attracted a loyal and dedicated following. Pirahna Bytes followed up with Gothic II in 2003 and just released Gothic 3 in 2006. Both games offered graphical and interface enhancements over their predecessors.

“When the scenery looks like a postcard, but the Hero wears his shield inside of his humerus, there are some major quality control issues going on.”

– Tim Tackett reviewing Gothic 3 on Game Revolution, Dec. 18, 2006.

In some ways, these games hark back to those aforementioned German imports, the Realms of Arkania series. The games have much to offer, but for some reason haven’t received the attention they deserve. While the strong competition has undoubtedly been a factor, there are other rationales for Gothic’s mediocre ratings. The second game suffers from bad voice acting and poor translations, and the third game has enough bugs to make an entomologist’s career.

Critics have remained unwilling to forgive the awkward combat system, though there doesn’t seem to be any hope for a general consensus on the overall quality of these games.

If the Ultima series was showing its age by 1999, SSI had entered a much steeper downward spiral by 1993. Although the publisher and developer had triumphed during the Golden Age with its TSR-licensed "Gold Box" and "Black Box" titles, unimpressive games like Spelljammer: Pirates of Realmspace turned fans away in droves.

Nevertheless, SSI trudged on for several more years, though they would eventually shift their focus back to strategy games before officially entering the "Where are they now?" file.

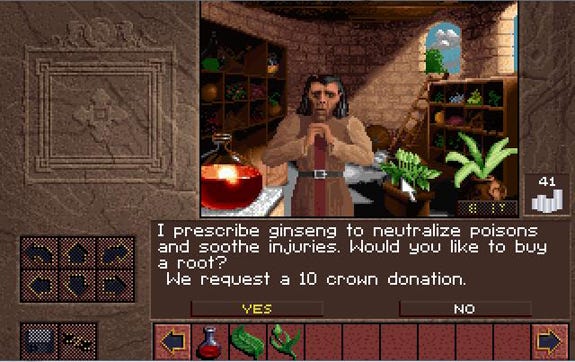

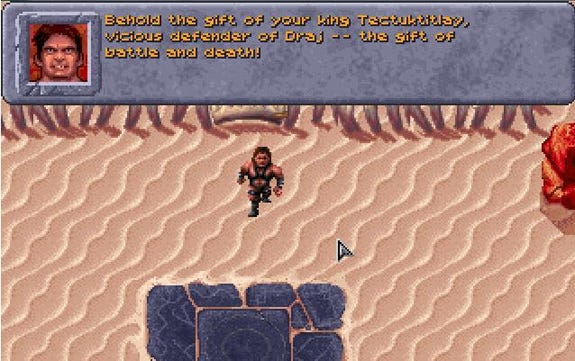

SSI developed and published other TSR-licensed titles after their Gold and Black Box heydays, but none seemed to command the respect of their earlier games. In 1993, SSI published Dark Sun: Shattered Lands, a top-down CRPG based on TSR's post-apocalyptic Dark Sun campaign. Despite an intuitive interface and intriguing setting, the game's mediocre graphics, jerky animation, typos, and buggy code kept it out of the limelight.

The Pirates of Realmspace introduced gamers to "steampunk," but nobody paid much attention.

SSI released a sequel called Wake of the Ravager in 1994, but even though the graphics were improved, the bugs were back. One particularly bad one was quickly dubbed "The Bug" among the many players who encountered it. The Bug would suddenly prevent monsters from attacking the avatar, making the game a cakewalk rather than the intense experience it was supposed to be.

Although such bugs would be easily enough addressed today by downloadable patches, such a practice wasn't widely practiced in the early 1990s. If you were unlucky enough to buy an early version of the game, you just had to live with the bugs.

Set in one of the lesser-known of TSR's campaign settings, Dark Sun: Shattered Lands didn't break any records.

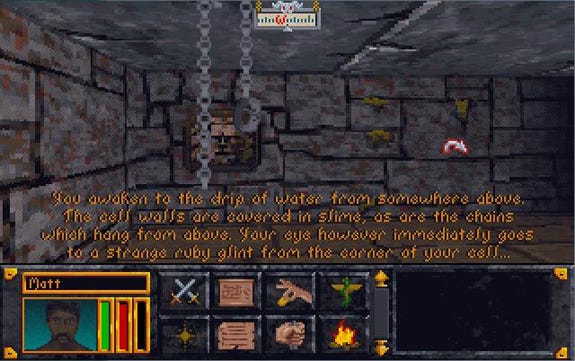

SSI also published games based on TSR's horror-themed Ravenloft campaign. The first of these, Ravenloft: Strahd's Possession, was developed by DreamForge and published in 1994. Like Ultima Underworld, Stradh's Possession is a first-person perspective, 3D game with smooth scrolling, though a "step" mode is available. A sequel named Stone Prophet appeared in 1995, offering enhanced graphics and some new abilities like flying and levitating.

Both of these games are based on "Gothic" themes and seemed poised to take advantage of the vampire fad spurred by Neil Jordan's Interview with the Vampire, which descended into packed theaters on November of 1994. Why these games didn't receive more recognition is a bit hard to determine. Perhaps they were damned by faint praise from critics, who couldn't find anything particularly good or bad about the series. In any case, these games are surely better than Take-Two Interactive's Iron & Blood: Warriors of Ravenloft, a truly rotten fighting game published by Acclaim in 1996 for DOS and Sony's PlayStation.

The last TSR-licensed game SSI published was the infamously wretched (and hard to spell) Menzoberranzan, which appeared in 1994 for DOS. Another first-person, 3-D game in the style of the Ravenloft games, Menzoberranzan seemed to have all the ingredients necessary for a hit. It featured one of TSR's most famous characters, Drizzt Do'Urden, a dark elf of the Underdark popularized by the novelist R.A. Salvatore. Furthermore, the developer (Dreamforge) had responded to earlier criticism and improved the game engine considerably.

Nevertheless, gamers quickly complained about the endless number of boring battles that dragged out the game and ruined its pacing. This is particularly noticeable in the crucial first stages of the game; the game requires considerable patience before anything remotely interesting happens.

The lack of strong sales in these games, and SSI's two dismal console action titles Slayer (1994) and Deathkeep (1995) were no doubt the straw that broke SSI's lucrative licensing agreement with TSR. TSR decided to eschew exclusive licensing and extended the franchise to several rival companies, most notably Interplay, who along with Black Isle Studios published BioWare's Baldur's Gate in 1998. I'll discuss some of these games in a moment.

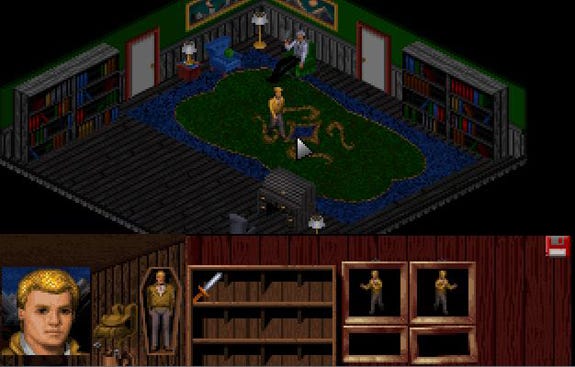

SSI also published several other CRPGs during this era, mostly developed by Event Horizon (later Dreamforge). These include The Summoning (1992) and Veil of Darkness (1993), both isometric games that again met with faint praise from gamers and critics. SSI released Alien Logic in 1994, an isometric game developed by Ceridus software based on the tabletop Skyrealms of Jorune RPG. Despite being praised for its innovative premise and gameplay, critics complained about the difficult install procedure and steep learning curve of the game's interface, and the game has faded into obscurity.

In 1995, SSI developed World of Aden: Thunderscape and co-developed (with Cyberlore) Entomorph: Plague of the Darkfall. Both of these games are based on a world similar to the one found later in Sierra's Arcanum; it's swords and sorcery meets "steampunk." The first game features first-person perspective, but the second reverts back to the familiar isometric perspective.

Sadly for SSI, these well-crafted and highly playable games seem to have attracted little interest from CRPG fans then or now.

Is it a CRPG or an adventure game? Just shut up and kill the vampire.

The story of SSI's slow but steady demise can probably be summed up in one phrase: Death by mediocrity. The company just couldn't seem to develop or publish another masterpiece like Pool of Radiance or Eye of the Beholder.

Games like Menzoberranzan and Shattered Lands just lacked the glamour of games from rival companies, and even better graphics and updated interfaces couldn't disguise the old engine under the hood. Sloppy coding and play-testing nailed the coffin shut.

Don't let the "ring" business fool you--Arcanum's "steampunk" masterpiece is far from the stereotypical "Tolkien-inspired" CRPG.

Although TSR was likely correct in their assumption that SSI was no longer the best company to represent their interests, they didn't exactly strike gold with their next few licensees. Many of these games were action or strategy titles, but there were a few CRPGs in the mix, such as Sierra's Birthright: The Gorgon's Alliance (1996) and Interplay's Descent to Undermountain (1998).

Birthright was developed by Synergistic Software and is a mix of adventure and strategy as well as more conventional CRPG elements. It’s based on TSR's highly successful Birthright game, and features a great story about a menace named "The Gorgon," who is hellbent on killing and extracting the divine blood of kings to secure his power. The game promised plenty of political intrigue and many multifaceted characters, and players can control not just single heroes but an entire kingdom. Finally, Birthright had Sierra's powerful name recognition behind it, which included their stunningly successful and highly innovative Quest for Glory series.

Unfortunately, Birthright: The Gorgon's Alliance failed for rather banal reasons. Yet again, a promising game was stymied with game-crashing bugs that irritated even the most forgiving players, but the bigger problem is that the game is a "jack of all trades, master of none."

Birthright wasn't content with being a strategy, CRPG, or adventure game--it tried to please fans of each of these genres. The result was a learning curve steeper than Mt. Everest, a fact that eliminated all but the most dedicated gamers right from the start. The so-called "adventure mode" is also rather tacked-on, and isn't well integrated into the gameplay as it should have been.

Although it has its moments, Birthright amounts to little more than a few freckles and a mole.

Think of a giant landfill, and thousands of unsold games descending into it.

Interplay's Descent to Undermountain is an even less satisfying game than Birthright. Descent to Undermountain attempted to ride some of the hype surrounding their immensely popular Descent series by modifying its 3-D, first-person shooter engine for use in a CRPG. The plan may have seemed like a good one, but an apparently harried production schedule resulted in one of the worst CRPGs of all time.

The task of transforming Parallax Software's brilliant FPS engine into a CRPG platform proved far more formidable than anyone had assumed. Besides sloppy coding and countless game-stopping bugs, the game suffered in general from a lack of polish. The levels were dreary and looked too much alike, and many players didn't appreciate their confusing, maze-like arrangement.

Poor graphics coupled with worse artificial intelligence added up to what we might expect--the game promptly descended into the landfill. Undoubtedly, TSR was beginning to wonder if it hadn't been better off with SSI!

Fortunately, things would soon take a major turn for the better with the publication of Baldur's Gate, the game that finally returned TSR-licensed CRPGs to the public eye. I'll return to this game momentarily.

So far, I've painted a pretty bleak picture of CRPG development in the early to mid 1990s, but things were not all bad.

Perhaps the key problems developers faced was how to bring the CRPG "up to date" after id's Doom and Cyan's Myst hit the scene. These two games had taken the industry by storm, and publishers were frantic to rush anything that looked like them onto the shelves.

By 1996, almost all serious PC gamers (and plenty of not so serious ones!) had upgraded their computers with the latest game hardware, which included CD-ROMs and expensive graphics and sound cards. Furthermore, what was formerly a forbidding mess of incompatible cards was solidifying into a few recognized industry standards, and a huge market was opening up for games that could really push this advanced hardware.

The publisher's creed was simple: Real-time, first-person perspective 3D or shareware. Origin's Ultima Underworld series fit the bill, but was too far ahead of the curve for most gamers to appreciate. Therefore, the field was open for some talented newcomers who could bring Doom-style graphics and gameplay to the CRPG, and a company named Bethesda soon had their foot in the door.

Bethesda entered the fray in a really big way with its Elder Scrolls series, which is still going strong today. The fourth game in the series, Oblivion was just released in 2006 and is selling quite well. However, those new to this fine series might not know much about its origins, or that it played an important role in the ongoing development of the genre.

The first Elder Scrolls game, Arena, was published by U.S. Gold in 1994 for DOS. Like its many sequels, Arena features real-time 3-D graphics in first-person perspective. It also boasts of a huge gameworld with over 400 cities, towns, and villages, all of which can be explored--it's a veritable cornucopia of CRPG delights.

Although it is not as well known today as Morrowind or even Daggerfall, you don't have to look too hard to find fans who rank it as not only the best game in the series, but the best CRPG, period. While I wouldn't go that far in my praise, it's hard to deny it a venerable place in the CRPG canon.

Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from Bethesda.

One way of thinking about Arena is as a combination of two Ultima games: The Stygian Abyss and The Black Gate. While Arena offered real-time, 3D, first-person perspective like The Stygian Abyss, it also features a realistic game world like The Black Gate's. Not only do players observe the passing of time from night and day, but it even rains and snows according to the season!

Indeed, it's really the sophistication of this virtual world that makes the game so notable. The plot--find the eight missing pieces of the "Staff of Chaos" and use it to rescue the Emperor from a dimensional prison--is hardly original. What impressed gamers was the incredible size of the world, the open-ended nature of the gameplay, and the supposedly high replay value (starting a new game reset the locations of quest items--though it's truly debatable how much this added to the game's replay value).

Though the game offers considerably more freedom of action than most games of its type (particularly regarding stealing items from merchants), players hoping to win still need to perform a fairly linear sequence of quests. Arena also has a nice combat system, in which the position of the mouse pointer determines which of eight types of attacks the avatar performs.

Nevertheless, the game is far from perfect. Like so many other games of this period, it suffers from bug-infested code. The battles are also quite a bit tougher than some gamers could handle, and the game's formidable specs limited its appeal to those with cutting-edge machines.

In any case, the game set a new standard for this type of CRPG, and demonstrated just how much room was left for innovation. Bethesda has been kind enough to re-release the game as freeware, and currently offers it for free download on their website. I only wish more CRPG developers would follow their lead!

"No longer forced to play the way The Man wants, we are now free to ignore the pleadings of the princess, wander off, and get involved in other complex tales that change and evolve in response to our actions!"

- Trent C. Ward in GameSpot, Sep. 26, 1996.

Bethesda followed up the modestly successful Arena with Daggerfall in 1996, a game that is still widely regarded as one of the most immersive CRPGs ever designed. Players were offered Tamriel, one of the largest gameworlds ever seen in a CRPG, and almost limitless possibilities for gameplay. The leveling system was also made more dynamic; players improved their skills simply by practicing it. Furthermore, the old rigid "class structure" was abandoned in favor of a much more open-ended guild system.

Players can customize their characters however they see fit, letting their creativity run wild. There is even an Ultima-style morality quiz option for players who don't want wish to muck about with statistics. In fact, many (if not most) players soon forgot all about the game's storyline and devoted their time simply to exploring Tamriel and honing their character.

Unfortunately, gamers were again presented with irresponsibly buggy code, though by this time they could probably use the net to find and install a patch to fix the worst. Another big problem is the lack of balance in the game's difficulty. It doesn't take experienced players long to gain enough experience to simply walk through the game, obliterating even the most powerful enemies with ease.

Bethesda developed and published two spin-offs before releasing the third entry in the official Elder Scrolls series. These were An Elder Scrolls Legend: Battlespire (1997) and The Elder Scrolls Adventures: Redguard (1998). Battlespire is in many ways a simplified version of Daggerfall, and is often described more as a first-person shooter than a true CRPG.

Redguard departs from the first-person perspective of the other games in favor of a third-person view, with the player's avatar visible on screen. If Battlespire leans towards the FPS, Redguard leans towards the traditional adventure game. Completing the game requires conversing with a great many characters and plenty of backtracking, but also some Tomb Raider-like action sequences including climbing, jumping, and swimming.

Although both games have their good points, neither seems to have won over as many fans as the main series. In any case, it's likely that Bethesda's team used these games as an opportunity to experiment with different interface and gameplay techniques.

Perhaps the best known of all the Elder Scrolls games appeared in 2002: The Elder Scrolls III: Morrowind. Morrowind combined the first-person perspective of the earlier Daggerfall with the third-person of Redguard--for the first time, players could choose between the different perspectives as they saw fit. Players soon discovered that each mode had its advantages. For example, third-person perspective makes it easier to dodge ranged attacks.

The leveling system had also been revamped a bit, and split into two: Primary Stats (speed, personality, luck, etc.) and Secondary Abilities (combat arts, magic arts, etc.). Primary stats only rose when the character gains a level, but secondary abilities improve with use. The system may sound complicated, but it's actually quite intuitive. Characters who run and jump often will see a spike in their acrobatics score. Characters who wield an axe will see their "axe" score raised, and so on. Besides just practicing a skill to gain experience, characters can also buy training or read special books sprinkled throughout the game.

"No matter what your preference, there's no right or wrong way to play Morrowind."

- From the Elder Scrolls III: Morrowind Manual

Indeed, there have been very few CRPGs as complex and flexible as Morrowind's. Even after I had completed the main quest, I still hadn't explored but maybe 60% of the incredibly massive and diverse game world.

Unfortunately, Morrowind has its problems. Like Daggerfall, players will eventually reach a level of experience that reduces even the game's most formidable foes into pushovers. There are also many ways to exploit the game's leveling system, such as standing in one place and casting the same spell over and over again. Nevertheless, the game continues to attract gamers and is still actively played today.

Bethesda produced two expansions for its third game: Tribunal (2002) and Bloodmoon (2003). Both expansions met with fairly good reviews, though the latter is perhaps the better of the two. I'll discuss the fourth game in a later section of this article.

Morrowind: Beautiful graphics, open-ended gameplay, boundless possibilities...See you next year.

Although Bethesda's CRPGs didn't necessarily bring anything new to the genre, they did introduce a nice alternative to the highly linear, story-based games that dominate CRPGs. Even though each of the games has a plot and a "main quest," players could choose to entirely ignore it, and many did so. More importantly, players were invited to indulge their creativity when selecting and developing their characters; the fun of these games is in customization. You build your character, not play someone else's.

Some critics argue that this degree of freedom puts these games closer to the original D&D tabletop game, in which good dungeon masters encourage players to take a more creative role in the unfolding of the adventure. Why not let a player dash past the monster, grab the treasure, and make a run for it? Why not let her swipe that armor when the merchant’s back is turned? Most games would require players to do the “right” thing, but Elder Scrolls let the player decide.

Naturally, other developers weren't content to let Bethesda dominate the real-time sector of the CRPG market. As soon as games like Arena and Daggerfall demonstrated the technical and commercial feasibility of real-time 3D graphics and the immersive potential of first-person perspective, several other companies jumped on the bandwagon.

Some of these games we've already mentioned, such as Shadows Over Riva and the last two Lands of Lore games. Shadows Over Riva hedged a bit; although exploration takes place in first-person perspective, combat is offered only in a somewhat cramped third-person isometric.

A more ambitious (though perhaps more misguided) effort was Westwood's Guardians of Destiny, the second game in their Lands of Lore series. Released in 1997, the game tried to take ride the wave of full motion video games and is loaded with live action scenes (think The 7th Guest or Gabriel Knight II). It also incorporates many arcade elements, including some timed sequences and lots of running and jumping.

The last game in the series, Lands of Lore III, ditched the live action actors for motion-captured animation and voice acting, but most critics consider it the weakest of the three. You are not allowed to create your own character, and critics complained about the repetitive gameplay, unbalanced graphics, and constant need to find food for the main character. It was also plagued with bugs, which certainly didn't improve the game's reputation.

By far the best known company to follow in Arena's wake is New World Computing, which adopted Bethesda's model starting with Might and Magic VI: The Mandate of Heaven (1998).

No doubt, Might and Magic fans were glad to see a new installment after some five years of waiting, and the game's coherent storyline and slightly more structured gameplay offered a viable alternative to Daggerfall. The box and manual sport beautiful artwork by the famed fantasy artist Larry Elmore, whose work graces many an Advanced Dungeons & Dragons product. Unlike the Elder Scrolls series, however, the player controls four characters instead of one (with the option to add two non-player characters later), and combat can be played in either turn-based or real-time modes.

Mandate of Heaven also gave players considerable leeway in how they developed their characters; after an initial choice of class, players decide how to expend "skill points." Skills are divided into four basic areas: Weapon, Armor, Magic, and Miscellaneous. This last category includes some über-skills like learning, which affects all the other skills by boosting the experiences points awarded after a battle. All in all, it's an intuitive and highly customizable way to handle the "leveling" issue.

I should add that the Might and Magic series also adopted the age-old convention of requiring players to first win enough battles to qualify for training, and then come up with enough cash to hire a trainer (many games simply "give" characters a level when they gain enough experience). Since cash is relatively hard for new parties to come by, players have to make strategic decisions about how to spend it--does it make more sense to buy a new weapon, magic scroll, or level up a character?

Although the combat system isn't perfect--all four characters are always on the front line and susceptible to frontal assaults--the game nevertheless won high praise from critics, and for good reason. Who can forget the first time their wizard cast a "fly" spell, sending the party soaring high above Enroth?

"It doesn’t matter what you call these instruments: crystal ball, computer, the Scry of Silicon; the Ordered Runes of Binaria, a keyboard, the Abacus of Turing. A rat, a mouse, the Rodent of Parc. They are Artifacts of Trans-Dimensional Manipulation and, with knowledge, you can command them to do your bidding.”

– From the Mandate of Heaven manual.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, Might and Magic VI was blissfully free of bugs. At a time when almost every other major CRPG was so riddled with errors that manuals advised players to routinely save the game every thirty minutes, such stability is nothing short of remarkable. Unfortunately, New World's quality assurance team soon lowered their standards to match the competition.

New World's next entry in the series, For Blood and Honor, is often hailed as the last good Might and Magic CRPG, even though it offers few innovations over its predecessor. Only a year had passed since the previous game, but the graphics engine was already looking dated. Moreover, the voice acting is more ingratiating than enduring, particularly after hearing the same few digitized samples for the ten-thousandth time. However, the sound is redeemed by an excellent operatic score by Paul Romero, produced by Robert King. The game also offers more races to choose from and a few other nice features, such as two possible endings.

After For Blood and Honor, the series entered a steep downward spiral. The next game, Day of the Destroyer, was released in 2000, and New World again decided to rehash the Might and Magic VI engine. The result of that decision was a game hopelessly behind the times graphically, but that wasn't the only problem. At least for old fans of the series, there was little thrill in starting over once again with a new set of characters and taking them through the motions once again.

Although the earlier games had certainly had their share of dull moments, Day of the Destroyer is almost painfully repetitive. Even the surprising decision to allow the player to create only one character (the rest of the party must be recruited later) does little to affect the monotony, since the additional characters are almost entirely devoid of personality and impact on the story.

The ability to add a dragon to the party might have been a nice feature, but doing so ruins the game's balance, reducing it to an unbearably dull walk through. As if these problems weren't enough to doom the game, other features like a three-tiered teacher system (expert, master, and grand-master) made long-suffering virtues out of note-taking and tedious back-tracking. Needless to say, very few fans were pleased with the game. Sadder still is the unforgivably buggy code, of which random crashes are some of the least irksome.

"It's a safe bet that nobody will ever wax nostalgic about Might and Magic IX."

- Brett Todd in GameSpot, April 12, 2002.

Day of the Destroyer may have destroyed most fans' faith in New World, but the company must have figured the horse was still worth one more beating. Perhaps it's a testament to the 9th game's overall lack of ambition that it lacks a proper name; it's simply Might and Magic IX.

The box promised "stunning" 3D graphics, and they were--indeed, who could believe that the company would release a game in 2002 with graphics that looked little better than Mandate of Heaven's, published four years previously. The game world also feels cramped compared to its predecessors. Applying the term "artificial intelligence" to the game's non-player characters results in an oxymoron.

Finally, there are more show-stopping bugs in the code than there are blocky polygons in the game. Suffice it to say, Might and Magic IX is just as tragic a way for a grand old CRPG series to end as Ultima IX: Ascension.

Day of the Destroyer was a disappointment, but the next game was downright embarrassing.

One fascinating aspect of the Platinum Age is how many companies managed to reach both their apex and their nadir within such a short span of years, but for different reasons.

From my vantage point, Origin's Ultima series ultimately faltered because Garriott and his development team kept attempting radical revisions to the game engine. During each transformation, more and more fans felt betrayed, until at last they could no longer acknowledge a game like Ascension as part of their beloved series.

New World Computing, on the other hand, were a bit too comfortable with their engine and gameplay mechanics and kept recycling them, much like Sir-Tech had done nearly a decade previously with its first three Wizardry titles. Eventually, even dedicated fans of Might and Magic grew bored with the repetition, and new gamers weren't likely to be won over with graphics that looked over five years old at release.

Thus, we might sum up this part of the story as a "Tale of Two Developers," noting how the first was defeated by ambition, the second by its lack. Only Bethesda seems to have found the right balance of innovation and repetition required to keep a series going strong over a period of many years, though only time will tale if The Elder Scrolls survives as long as Ultima and Might and Magic.

So far, the best Platinum Age innovations in the CRPG genre have been in two realms: The rise of real-time, 3D graphics in first-person perspective, and the development of huge, highly interactive game worlds.

CRPG developers had climbed aboard the bandwagon begun by first-person shooter games like Doom and Quake. The usual refrain heard from fans of this type of game are that they are inherently more "immersive." You don't just play a character; you enact a role.

If this were true, you might expect that all successful CRPGs released after Ultima Underworld and Arena would follow their example. However, three of the most celebrated CRPGs of all time that emerged from this period offered only an isometric, third-person perspective: Diablo, Fallout, and Baldur's Gate.

Blizzard is probably better known today for World of Warcraft MMORPG, which is loosely based on the company's best-selling real-time strategy series, Warcraft, which launched in 1994 with Warcraft: Orcs & Humans. Blizzard also made gaming history with the release of StarCraft in 1998, which was immensely successful and is widely regarded as the finest real-time strategy game ever developed.

Nevertheless, the publication of Diablo in 1996 remains one of the most divisive moments in CRPG history. Even today, nearly a decade later, no other game has polarized CRPG fans more than Diablo. Are Diablo and its sequel the best CRPGs ever made or the worst? At least among experienced fans of the genre, the jury is still out. Let's take a closer look and see if we can understand the source of this contention.

Blizzard boiled down the CRPG to its bare essentials--and brought thousands of new gamers to the genre.

Diablo is usually described as an "action" CPRG, set in real-time. It's also features a vastly simplified character development system compared to most CRPGs. The player only controls a single character, who can be one of three basic types (Warrior, Rogue, and Sorcerer). The differences among these types are somewhat superficial; warriors can cast spells and sorcerers can wear armor. However, the choice of class does determine the best strategies for surviving battles, and, as usual, it's the magic-using class that starts off weakest and ends up strongest.

Each time the character gains a new level, the player receives five points to distribute among the four attributes: strength, magic, dexterity, and vitality. Although seemingly quite simple on the surface, Blizzard's genius was doing more with less. Instead of baffling players with a complicated skill system like those in the Elder Scrolls or latter Might & Magic games, Diablo offers fewer choices but made them more significant.

The result was a game that met the grand old qualification, "Easy to learn, hard to master." To put it bluntly, if you can click a mouse button, you can play Diablo. Even gamers who had never played a CRPG before found it intuitive and addicting. Furthermore, the production values were high, with great graphics, impressive cut-scenes, and a magnificent musical score. The game quickly became a best-seller, and is still being sold as part of the Diablo Battle Chest!

"Diablo is the best game to come out in the past year, and you should own a copy. Period. If you like PC games, you should go out right now and experience what is likely to be the clone maker for the next two years."

-Trent C. Ward on GameSpot, Jan 23, 1997.

Diablo is also noted for its high degree of randomization. Everything from the dungeons, monster locations, and item capabilities are randomized, ensuring not only surprises but also upping the game's replay value. Of course, readers of this series will be thinking back to my earlier discussion of Rogue and games like The Sword of Fargoal, which also offer relatively simple "hack'n slash" fun in randomized environments. Indeed, one of the most common epithets given to the game is "a Rogue-like for the 90s," though there are plenty of Rogue fans who would object to this comparison.

SSI had tried something similar with its Dungeon Hack game and editor back in 1993, which tried to marry the venerable old mainframe classic with its Eye of the Beholder engine. Again, one has to wonder why so many developers seem to miss the point that it's precisely the lack of distracting graphics and complex interfaces that make the classic Rogue games so novel and playable.

Another aspect of Diablo that set it apart was its support for multi-player, which ranged from the by-then common LAN party setup to a new internet server named Battle.net. Although not without its flaws (cheating was rampant), Diablo's multi-player capability remained a significant factor in the game's long-lasting popularity.

Yet despite strong sales and praise from many prominent reviewers, Diablo was not without its naysayers. Not surprisingly, the game's popularity with "virgin" CRPG gamers drew sneers from long-term fans of the genre, particularly those who'd cut their teeth on venerable old titles like SSI's Pool of Radiance or Interplay's The Bard's Tale. Blizzard had seemed to reduce the often intimidating CRPG genre to its bare essentials, then poured on the eye-candy.

Oldsters scoffed, dismissing the game as a "clickfest." Meanwhile, fans of games like Sierra's Quest for Glory were turned off by the lack of characters and interesting scenarios; for them, the constant clicking and killing brought little more than tedium. Other players complained about the "dark" graphics, which were occasionally hard to make out. The on-screen automapping tool helped with navigation, but frequently obscured the battle sequences.

Finally, some players complained about the game's relatively short duration; gamers accustomed to the hundreds of hours required to slough through an Ultima weren't happy about a game that could be completed in a mere two days.

What happens next in the Diablo story is quite perplexing. Rather than release a sequel or their own expansion, Blizzard let Sierra On-Line publish an expansion named Hellfire, which had been developed by Synergistic Software (the same team responsible for Birthright: The Gorgon's Alliance). This expansion appeared in 1997, and added two new dungeons, new creatures, spells, items, and a Monk character class.

Reviewers weren't nearly as enthused about Hellfire as they had been about Diablo, and the lack of multi-player support vexed many players. Many fans of the series don't consider it an "official" expansion.

It wasn't until 2000 that Blizzard finally released the true sequel, Diablo II. This game was more complex and larger than its predecessor, and the updated graphics were as impressive as Diablo's had been in 1996. Now, players could explore outdoor areas as well as dungeons. More importantly, the randomized quests were replaced with more linear ones, which allowed for a more tightly integrated storyline and cut-scenes.

The class system had also been reworked, with five (Paladin, Barbarian, Amazon, Necromancer, Sorceress) classes, each with their own unique skills. Leveling up is also a bit more interesting with a graphical "skill tree" system that helps sustain a player's long-term interest in developing a character--there's always some new amazing new ability just a few levels away.

Multi-player mode was better supported this time, and cheating was rarer. Nevertheless, their Battle.net server was prone to lag, though that didn't seem to slow the onslaught of rabid Diablo II fans desperate for online play--a fact that rankled many gamers who had just plunked down $60 or even $70 for the game. Finally, some of the Carpal Tunnel-inducing mouse clicking was alleviated. Players could simply hold down the mouse button to have their character repeatedly attack or move around.

The second game gave rabid fans exactly what they wanted, and then some. And then some more.

Blizzard decided to make their own expansion this time, releasing Lord of Destruction in 2001. Besides many new items and quests, this expansion offered heightened screen resolution (800 x 600), and two new character classes (Assassins and Druids).

Reviewers were pleased with the improved graphics, as well as many improvements to the Battle.net server that improved the online multi-player experience.

Diablo II greatly expanded the leveling up process with an ingenious skill tree system.

If the only criteria we needed to evaluate a CRPG were its sales figures and enduring popularity, Blizzard's Diablo would represent one of the best (if not the best) CRPG ever designed. The game brought new blood to the genre, introducing it to thousands of gamers who had never played any of the classic CRPGs, much less a tabletop D&D game. It sent hordes of badly behaved teenagers (and middle-aged men, no doubt) scampering to Battle.net, "pwning" each other and seeking out the latest cheats and hacks to gain an unfair advantage.

Diablo and Diablo II are truly CRPGs for the masses. At the risk of sounding like a jaded old curmudgeon, I can't help but feel a pang of regret about the overwhelming triumph of this series, since it seems to have come at the expense of the older, more sophisticated CRPGs of past eras.

Given the unmitigated success of Blizzard's Diablo, even the dimmest market analyst could predict the inevitable rush of clones that would follow in its wake.

Many of these games were just flashes in the pan. These include Silver Lightning's Ancient Evil series (1998, 2001), Iridon's Dink Smallwood (1998), Strategy First's Clans (1999), and Sierra's Throne of Darkness (2001). Though each game has qualities that set it apart from Diablo, none have matched its success.

Dink Smallwood was programmed by Seth Robinson, whose Legend of the Red Dragon game we discussed in the last installment. Like that game, Robinson loaded up the game with humor and satire, but it failed to make much impression on the market. Clans introduced more adventure-style puzzles into the mix, whereas Throne of Darkness is set in Japan's Middle Ages, just as Pixel Studio's later Blade & Sword (2003) took players to ancient China. Rebel Act Studios' Blade of Darkness (2001) is known only for its outrageous gore.

Better known Diablo clones include Gathering's Darkstone (1999), Electronic Art's Nox (2001), Irrational Games' Freedom Force (2002), Larian's Divine Divinity (2002), and Encore's Sacred series (2004). Darkstone introduced 3D graphics and the ability to control two characters, though only one at the time (the other is controlled by the computer). The ability to zoom and spin the camera around eliminated many of the problems introduced by Diablo's isometric view (such as objects getting lost behind structures.

Nox, developed by the famed Westwood Studios, met with good reviews and enjoyed modest success. Westwood even offered an expansion for the game, Nox Quest, and in a surprising move made it available for free download. Freedom Force introduced comic book style superheroes and is probably the best of the bunch. It offered a viable alternative to the "dark" fantasy of Diablo and more tactical combat. Vivendi published the sequel in 2005, Freedom Force vs The 3rd Reich. Divine Divinity and its sequel, Beyond Divinity (2004), are essentially Diablo on steroids, with huge worlds and a massive number of skills (500!). These games also improve on Diablo's sometimes confusing navigation interface. Reviewers tended to scoff at their derivative nature, but praised them for their addictive gameplay and attention to detail.

Sacred goes a step further, offering full 3D views and a world that take hours to cross. This game met with plenty of praise from critics as well, who applauded its more open-ended structure, but its bugs haven't gone unnoticed. In any case, Sacred seems to be the best action CRPG going, even if its depth and complexity go far beyond the model established by Blizzard's Diablo.

No doubt it will be interesting to see how far developers can continue to push the boundaries of the action CRPG, since each layer of complexity alienates the type of gamer who was so strongly drawn to Diablo, where the only thing you needed was a fast button finger.

Taylor has, in essence, reinvented the fantasy adventure by creating a world that isn't attached to stereotypical races and archetypes that are often more, than merely, inspired from the works of Tolkien or Dungeons & Dragons.

– Peter Suciu on GameSpy, Apr. 12, 2002.

Perhaps the best known of the more recent action-CRPG is Gas Powered Games’ Dungeon Siege series, which debuted in 2002. Conceived by Chris Taylor and published my Microsoft Game Studios, Dungeon Siege features a large, diverse gameworld rendered in real-time 3D. Furthermore, the game’s custom engine allows the gameworld to “stream” rather than pre-load, which helps make it feel more like a coherent whole rather than a collection of discrete areas.

Dungeon Siege’s leveling system is determined by the character’s actions rather than a pre-selected class, an innovation also seen in the Elder Scrolls series. Although the player can only create one character, he or she can add up to eight other pre-rendered adventurers or loot-carrying mules to the party.

Although critics appreciated the lack of loading times and open-ended leveling system, they chided the simplistic “hands off” gameplay and straightjacket plot. An expansion called Legends of Aranna followed the next year, introduced a new campaign and several improvements, such as a global map tool, but was greeted with lukewarm reviews.

Dungeon Siege looks great, but many critics panned the "click and watch" gameplay.

Gas Powered Games released the first full sequel, Dungeon Siege II, in 2005. Although the bulk of the gameplay is similar to the first game, a new Diablo II-like skill tree system gives players more refined options for leveling their character.

The first expansion to this game, Broken World, was published by 2K Games in 2006. Although it’s a bit early to tell what impact these games will have on the genre, along with Sacred they are at least keeping the “action CRPG” alive and well on the PC.

After Daggerfall and Diablo, the typical CRPG fan probably assumed that real-time gameplay, whether 3D or isometric, was the way of the future. However, as we saw in the last article after the publication of FTL's Dungeon Master, the evolution of CRPGs is anything but linear.

Ultimately, craft trumps innovation, and even though Dungeon Master demonstrated as early as 1987 the feasibility of first-person perspective in real-time, SSI's turn-based Gold Box games sold well into the 1990s. Therefore, there's really nothing surprising about Interplay's breakthrough success with Fallout, a turn-based isometric game set in a post-apocalyptic wasteland.

Let's cut right to it. Fallout and its sequel, Fallout 2, are two of the finest CRPGs ever made, and if the era that produced them isn't worthy of the name "Platinum," I need a new dictionary. Like Interplay's previous masterpieces The Bard's Tale and Wasteland, Fallout is one of those preciously rare games that represents more than just the sum of its parts.

I'll offer the standard disclaimer--Fallout is one of my favorite games, and my love for it has no doubt blinded me to at least some of its flaws. My advice is that if you suspect that my praise is overblown, seek out the game and try it yourself. These are tremendously creative games that continue to win over new players nearly a decade after they first appeared on the shelf.

But what is about Fallout that makes it so great? Haven't there been plenty of other post-apocalyptic games, such as the aforementioned Wasteland, Origin's Autoduel, and even Interstel's Scavengers of the Mutant World? Doesn't it also rip its leveling up system from games like Mandate of Heaven and Daggerfall?

"Welcome to Vault-13, the latest in a series of public defense works from Vault-Tec, your contractor of choice when it comes to the best in nuclear shelters. Vault-Tec, America's Final Word in Homes."

-from the Fallout manual.

If I had to sum up Fallout's appeal in one word, it'd be "style." The governing aesthetic is a surreal mix of cheerfully morbid 1950s Cold War imagery and movies like Mad Max, Planet of the Apes, and Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb. There are even hints of The Evil Dead tossed in for good measure.

This juxtaposition makes for some of the most compelling moments in gaming history, and I doubt there is anyone who doesn't get goosebumps the first time he witnesses the introductory cut-scenes. Furthermore, the aesthetics run all the way through the game, including the interface.

Most games switch to a boring menu screen full of numbers when it comes time to level up. Fallout presented skills on "information cards" complete with chillingly cheerful illustrations to keep up the disturbing ambiance. Even the game's manual stayed "in character," presenting itself as a "survival guide" designed to look like a government publication.

Indeed, the manual refers to the game as a "simulation" to help long-term Vault-Dwellers more comfortably prepare themselves for a return to the outside world. It even includes some "survival recipes" for "Mushroom Clouds" and "Desert Salad." It's more than obvious that the development team had a blast creating Fallout, and their enthusiasm radiates throughout.

Few games are as aesthetically pleasing--and disturbing--as Fallout. Besides, ain't it cool to kill rats with brass knuckles?

The story is an intriguing blend of alternate history, dystopia, and science fiction, and good enough to keep the wheels of your imagination spinning long after you've completed the game. It goes something like this. Some 80 years ago, a nuclear holocaust wiped out most of the civilized world, but your people survived by moving into a giant underground vault, where they eventually developed their own society and culture (think Logan's Run).

However, now the vault's water purification chip has worn out, and it's your character's job to find a new one, fast. That means leaving behind everything you've ever known. What seems like a fairly straightforward fetch quest soon becomes much more, and I'm not going to ruin the story here by giving away any of the many twists and turns. Suffice it to say, no one who has played this game will have trouble remembering what happens when you complete this mission.

Fallout 2 was developed by Black Isle Studios, Interplay's new division that specialized in CRPGs. The second game is set 80 years after the conclusion of the first game, and has echoes of the movie Mad Max: Beyond Thunderdome running through it. Your avatar's tribe is on the verge of extinction, and has been assigned the task of hunting down the G.E.C.K. (Garden of Eden Creation Kit).

Once again you quickly find yourself immersed in a moving and captivating story, and it's hard not to get personally invested in its outcome. The game culminates in one of the most heart-pounding (and difficult) climaxes of any game I've ever played. Fallout 2 also offered better dialog options and plenty of new items and characters. However, the bulk of the game's engine was left intact.

Although bothFallout games were critically acclaimed and beloved by fans, Interplay did not produce a third game. Fallout Tactics: Brotherhood of Steel (2001) is a strategy game based on Fallout's combat mode, though it does have some CRPG elements. A Diablo clone called Fallout: Brotherhood of Steel appeared for the PS2 and Xbox in 2004, but most fans of the first two games don't care to acknowledge it.

According to an official 2004 press release, Bethesda is currently developing Fallout 3, though it may sadly turn out to be only radioactive dust in the wind. In any case, it would be nothing short of a miracle for another team to match, much less surpass, Black Isle's post-apocalyptic masterpiece.

Black Isle wasn’t the only company releasing brave new CRPGs that were willing to abandon the old swords and sorcery formula.

A company named Troika scored a triumph in 2001 with Arcanum: Of Steamworks & Magick Obscure, a game published by Sierra that quickly gained a large and devoted cult following. It certainly wasn’t the first CRPG to try to marry magic and technology; many of the early Ultima and Might & Magic games blended the two quite freely, but SSI’s Spelljammer: Pirates of Realmspace is probably a more direct precursor. At any rate, Arcanum is the game people think of when they hear the word “steampunk,” and deservedly so.

Arcanum is most often praised for its open-ended gameplay and intriguing game world, which is best described as an industrial revolution taking place in the midst of a high fantasy setting. Usually, magic and technology are pretty strange bedfellows, but when done right (as in Arcanum), the result is “magical realism,” in which objects that would ordinarily look familiar are placed in settings that make them seem strange and exotic.

It can be quite exhilarating, for instance, for a dwarf to draw a flintlock pistol rather than the clichéd old axe or hammer. The outcome of the game depends on whether players follow the magical or the technological path; the choice is left to the player.

"If you're serious about role-playing games--so serious that you don't care about graphics but instead just want to immerse yourself in a different world and try to explore it, perhaps even exploit it, as fully as possible--then Arcanum is well worth the investment of time, money, and effort.”

–Greg Kasavin on GameSpot, Aug. 21, 2001.