Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Stardock's Jon Shafer, who previously led development of Civilization V at Firaxis, explains how it's possible to create a game full of "very interesting and very difficult decisions."

Stardock's Jon Shafer, who previously led development of Civilization V at Firaxis, explains how it's possible to create a game full of "very interesting and very difficult decisions."

Knowledge is power. Game designers ignore this old adage at their own peril. As developers we want our games to empower people to live out their fantasies, but all too often the games themselves get in the way.

Whether in games or in life, we've all experienced that uncomfortable feeling of having no idea what to do. Most games require players to make a vast number of decisions, and if they're not provided enough information to make those choices confidently, the end result is nearly always frustration.

In this article we'll examine in detail the role of information in games, why meaningful choices require context and the consequences of omitting it. We'll also look at a few examples of how, in unique cases, hiding some things can actually make a game better.

A designer's goal is always to make every decision the player faces interesting. An "interesting decision" is when a player has two or more options which are (roughly) equal in value over the long term. Conversely, there are two main factors which can make decisions uninteresting: when one option is clearly better than all others, and when the consequences of the options are unclear.

If someone is confused by a decision, their feelings toward the choice will range from ambivalent to annoyed. With no context, they'll simply choose the option that is easiest, sounds coolest, or (gulp) is first in the list. It's impossible to be heavily invested in such arbitrary decisions, and if the excrement hits the fan later on, they're much more likely to blame the game than themselves.

After people fail, the goal should be for them to think, "Dang, I really should have chosen X back there instead of Y. Let me try again and see if I can do better." This only happens if players feel like the game was fair and sufficiently prepared them for what was to come.

If you want players to really be making strategic decisions, then the mechanics of the game need to be laid bare. For example, a game with upgradeable equipment needs to fully explain the consequences of equipping a weapon.

Knowing how much more damage you'll be doing is much more useful than being told the player's mysterious and arbitrary attack value is increased by 5. Five what? It's not a big deal if all you're dealing with are weapons with a single attack value, but what if you have to choose between a +5 attack weapon and a +7 defense shield? How does one compare their value without a full understanding of what these stats actually mean?

Another major issue with making uneducated choices is that it's hard to get excited about them. You feel a real sense of progress knowing your old weapon did 10 damage per swing and could kill those monsters with four hits, but that new one you bought does 16 per hit and can kill them with only two swings. Just knowing that now you'll do "more damage" doesn't provide quite the same thrill.

When you know exactly what's going on, that's the point at which a game really takes off. This provides the opportunity to start making plans, and the trade-off between short-term and long-term interests becomes a very tough call. If players are able to reach this level of comfort, they're likely to stick with a game for the long haul.

While providing players with as much information as possible is usually ideal, there are situations when it can hurt a game. One such case is when the players have perfect information -- that is, they know everything there is to know.

While providing players with as much information as possible is usually ideal, there are situations when it can hurt a game. One such case is when the players have perfect information -- that is, they know everything there is to know.

A good example is the game checkers, where the entire board and all pieces are visible. There are no elements of the game itself which are hidden from either player.

Nearly every game needs some element of surprise, and "pure" strategy games are the best example. In many cases, this element is provided by other players, be they human or AI. If you always knew exactly what your opponent's next move was, there wouldn't be a whole lot of tension!

Solitary games that lack an unpredictable opponent need some other way of spicing things up, and some form of randomization is virtually always the answer. The solitaire card game that nearly everyone is familiar with uses a randomized deck. If the card order was the same every time, there would be almost zero replayability.

However, it's not just the games without human players that are seriously damaged by perfect information. The aforementioned checkers was recently "solved" -- meaning if neither player makes a mistake, the end result will always be a draw.

Having some form of hidden information is a crucial element to preventing a single strategy from dominating. In many strategy games, there is a "fog of war" which covers the map, and exploration is necessary to reveal what lies in the darkness.

Sometimes even the map itself changes over time. For example, in the recent Civilization games, technological research reveals new resources. Their sudden appearance can greatly alter the "perfect" strategy for a given situation. This constant need to adapt to previously unknown circumstances is a big part of what makes games fun.

Hidden information is especially important in single-player games where AI opponents are simply executing lines of code written by a human programmer. In most games it is nearly impossible to develop an AI that will compete with the best of the best. If the human player is also able to see the entire game situation clearly, it's only a matter of time before the AI's patterns are learned, dissected and ruthlessly exploited. A game solved in this manner quickly loses whatever charm and joy it once held.

The amount of information that "should" be hidden can vary greatly, and ultimately depends on the preferences and goals of the designer. The card game Dominion makes 10 random action cards available to players at the beginning of each play session, and the inability to predict the order in which cards are drawn provides a great deal of replayability.

However, those who have played enough games will begin recognizing the optimum strategies for a given set of action cards, and Dominion has become formulaic for some. Adding more randomization or hidden information would probably improve the game for these players, but it might also make it less enjoyable for others. Hey, game design is more art than science.

The goal is to require some form of trade-off with every decision. One example of this is choosing between a smaller but safer bonus, and a riskier but much more powerful one.

This generally works best if the safer bonus is safe simply because it pays off in the short term while the other option pays off later and is riskier because other factors can come into play.

If the choice is basically just between "25 percent chance something really good happens" and "75 percent chance something okay happens" you're not really making a strategic choice as much as you're gambling.

While this can be made to work, it's tough to make an interesting decision out of swinging a large weapon that only hits 50 percent of the time but does 50 damage or using one that hits 90 percent of the time and does 25 damage.

More often than not players will go with the safer option (especially if they try using the big one and it misses three times in a row -- good luck getting them to try using it again!) This sort of mechanic is fairly rare in modern games, but I still see it pop up in a few Japanese RPGs.

You can find good examples of short term safety versus longterm risk working really well in pretty much any sports team management sim where there is a longterm player development aspect or the risk of injury/underperformance.

Chrono Cross

I've been playing a lot of the text-based sim Out of the Park Baseball for the last six months or so, and there have been some agonizing decisions -- should I trade this guy in his prime for a collection of younger, less-developed and much riskier prospects? Do I send off a package of two risky prospects in exchange for one safer one? The inability to predict the future coupled with an understanding of the game's mechanics, the likelihood of certain types of prospects panning out, the players' injury history, the value of certain types of positions, etc. all combine to provide a set of very interesting and very difficult decisions.

This sort of trade-off can be applied in nearly any game. Should I declare war on my neighbor, hoping that the resources I expend to capture their lands add up to less than what I stand to gain? Is it worth the risk to attack that optional boss and try to open up a new area to explore? Players need to be equipped with some measure of information for this to be possible, but don't underestimate the positive impact imperfect knowledge can provide.

I know some people disagree with me on this topic and claim that a game needs to be "more than just numbers." You won't find me arguing against the value flavor and "feel" provide. There are an innumerable number of valid design approaches that can result in a game enjoyed by a large audience. The point is simply to recognize that when it comes to game mechanics there's basically a scale that has strategy at one end and flavor at the other.

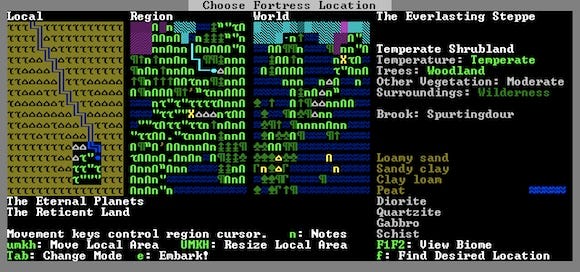

One great example of a game which definitely doesn't go out of its way to share everything with the player is Dwarf Fortress, which is all about exploring the game space and laughing as all sorts of crazy things happen. While most players don't like there being a risk of drinking a potion and the game permanently ending right then and there, there are absolutely some who do and we developers definitely shouldn't write them off. The roguelike genre in general is characterized by this possibility of a single mistake derailing everything.

Dwarf Fortress

Every development team has to decide for itself where on the spectrum of strategy-vs-flavor it wants to land. What is the goal of the game? Who is our target audience? What do we want players to feel when certain events happen? No gamer is the same and no game should be either.

A point I often make when discussing game design is that the only manner in which a game really matters is inside the player's head. You could have the coolest, most complex system modeling some really interesting phenomenon... and it's completely irrelevant unless the player knows what's going on and how to have fun with the situation. When someone understands the mechanics and the implications of their decisions and is able to translate that into a completely unique experience -- that's when a game really succeeds.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like