Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

The legendary creator of Pitfall! talks about his time at Atari, the founding of Activision and describes what he's been up to until the present day, taking us through the crash, into his cult classic Little Computer People, and beyond.

[In the writing of his history of the video game industry, Replay, author Tristan Donovan conducted a series of important interviews which were only briefly excerpted in the text. Gamasutra is happy to here present the full text of his interview with legendary Pitfall! developer David Crane.]

In the latest in our series of interviews conducted by Tristan Donovan for his book Replay: The History of Video Games, the author catches up with Activision co-founder David Crane.

Crane's career dates back to 1977 and the list of the games he has made is just as long. Some of his best known include the Atari VCS2600 classic Pitfall!, Ghostbusters, Little Computer People, and fondly remembered NES game A Boy and His Blob. He was also involved in creating the controversial Night Trap.

In the interview, Crane discusses his time at Atari, the formation of Activision, the original third-party publisher, the evolution of game development and what he has in common with Charles Shultz.

When did you join Atari?

David Crane: I joined in the fall of 1977. I was playing tennis with Alan Miller when he let me know he had been tasked with finding game programmers for Atari. It sounded more interesting than working in the integrated circuit design group at National Semiconductor.

One night after tennis, Al asked me to proofread the newspaper ad he had written for attracting game designers. I liked what I read. I went into National that night, wrote up a resume on a computer that I had designed and built, interviewed the next morning at 10am, and had the job by 2pm.

Had you made games before?

DC: I had designed games all my life. I was the kid in the neighbourhood who was asked to modify the rules of a four-player board game to work for three players, etc. In college I designed an unbeatable Tic-Tac-Toe-playing computer that still works today. It used 72 discrete integrated circuits wire-wrapped together and a unique display based on polarized light.

Which of your Atari games are you most proud of?

DC: In the early days we were asked to make home versions of Atari's popular arcade games. That can be a big challenge when you consider that an arcade game was a $4,000 video computing system with a lot of memory and computing power. The $150 VCS 2600 was weak and tiny in comparison.

DC: In the early days we were asked to make home versions of Atari's popular arcade games. That can be a big challenge when you consider that an arcade game was a $4,000 video computing system with a lot of memory and computing power. The $150 VCS 2600 was weak and tiny in comparison.

Despite the limitations, I made a home version of Canyon Bomber and Depth Charge in a single 2Kb VCS cartridge: the height of elegance in the porting of arcade games.

How has the nature of game development changed since then?

DC: Game design in that era was extremely technical. You didn't actually design a game and then implement it on the hardware. You figured out what the hardware could do and then worked that into something fun.

So, with the game development process working bottom up rather than top down, there was no way for management to tell the programmers what to do. Those of us who thrived in that environment had both left- and right-brain skills. We could be very creative and very technical at the same time, and that turned out to be a rare skill set.

As games got more complex long after Atari, those of us who had proven themselves in a one-man, one-game environment became project leaders. George Lucas could make a movie all by himself - operate the camera, block the shots, edit the film, etc. - but he makes better films by using specialists with a singular focus on their individual tasks.

In the same way, while I can draw pixels, there are many artists who can do better. Same with sound effects, music, etc. Game development became more specialized as projects became larger, and teams grew up to do what we used to do completely by ourselves.

By the end of the 1970s, many of Atari's game programmers were getting fed up with the lack of recognition for their work. What was the cause?

DC: The frustration began when Atari refused to pay a bonus program that was believed to be in place. Our department manager had negotiated a small royalty based on unit sales, and when he later asked about that he was told "What royalty?". To stop the grumbling, managers went through and gave raises to key employees, but a line had been crossed when the company started to break promises to its valuable employees.

And that led you to co-found Activision…

DC: The pivotal event in the process can be traced to a memo from Atari's product marketing group. This was a one-page list of the top 20 selling cartridges from the previous year, with their percent of sales. The purpose of the memo was the hint: "These type of games are selling the best. Do more like these."

But this memo also showed us whose games did well, not just the game type. We noticed that four of the designers in a department of 30 were responsible for over 60% of the sales. And since we knew that Atari's cartridge sales for the prior year was $100 million, it was a shock to know that four guys making $30k per year made the company $60 million. That will get anyone thinking about a piece of the pie.

The four of us took this little sales statistic up to the then company president, Ray Kassar. Our point was that the statistics showed we must be doing something better than others. Since a game is a creative product, it is possible that one person is more creative than another and therefore should be compensated accordingly.

We were told: 'You are no more important to Atari than the guy on the assembly line who puts them together. Without him we have no sales either.' We were gone within days of that meeting.

Manny Gerard, the Warner executive in charge of Atari at the time, believes it would have made no difference if Kassar did what you wanted. His argument is that entrepreneurially-minded staff would have left anyway in reaction to Atari getting bigger and more corporate.

DC: Manny might have a point. While you will lose employees by treating them unfairly, it doesn't necessarily follow that treating them well will keep them. But Atari could have provided the compensation and public recognition that I got from Activision. If they had done that on that day, and not done me the favour of driving me away, I would probably still be there.

In a break with the industry status quo at the time, Activision made a point of naming the author of its games. What reaction did you get from players?

DC: This actually provided all of the positives of celebrity and none of the negatives. I can assure you that I was never chased by the paparazzi, but in certain circles there was pretty good name recognition.

But the real thrill is hearing directly from a game player that your work touched them in some way. Because there was a name and a face behind the game, players were able to let me know directly how much they enjoyed playing one of my games.

That idea of game makers as celebrities hasn't really taken off though. Why do you think that is?

DC: Think more "book author" than "pop star". The recognition we sought was that of the author of a creative work of fiction. Like most people, I have my favourite authors and I know that I will buy their next book on the strength of their last.

The authors of games ought to get the same recognition now as in the '80s. But these days, there might be 100 people involved in a game. In the era you are discussing, there was only one. That changed, and so crediting the work as the product of a single creative mind has gone by the wayside.

What inspired your Pitfall!, your big 1982 hit?

DC: Games in the early '80s primarily used inanimate objects as main characters. Rarely there would be a person, but even those weren't fully articulated. I wanted to make a game character that could run, jump, climb, and otherwise interact with an on-screen world. I had actually created what I called my 'little running man' about two years before Pitfall!, but each time I tried to incorporate him into a game I didn't find the inspiration.

One day after finishing a game, I decided that I would try again. This time, after only about 10 minutes I had a sketch of a man running on a path through the jungle collecting treasures. Then, after 'only' 1,000 hours of pixel drawing and programming, Pitfall Harry came to life.

The early '80s were a big boom time for games, especially in the US. How did it feel to be working in such a fast-growing branch of entertainment?

DC: I was having a blast. Everybody wants to have their life's work appreciated, and our games were at the centre of attention. But more than that, I had found my calling in life. I am the only game designer from the 1970s who is still doing it every day. Yes, I am still programming games 32 years after my first. While the business has grown, I have been in it the whole time. So to me it has just followed a natural evolution.

The crash that followed in the US in 1982/1983 has largely been blamed on a deluge of poor-quality VCS games. Do you think this was the cause?

DC: The crash was largely caused by a glut of poor product. In fact, Activision was the main cause – although indirectly. Activision was a huge hit in the early '80s. We showed that you don't have to spend $100 million to produce a game console to make money in video games.

In one six-month period, 30 new companies sprang up trying to duplicate our success. What they didn't realize is that our success was due to the best game designers in the world – not just our business model. These companies had to make do with amateur game talent, and the products were mostly awful.

We even predicted the crash. I remember saying that "none of these companies will be in business in a year". How prophetic. What we didn't realize is that each company already had a million game cartridges in their warehouse when they went under.

It was the sale of these games by liquidators that flooded the market. They bought them out of bankruptcy for $3, sold them to retailers for $4, and the retailers put them in barrels at the front of the store for $5. When dad went in to buy junior the latest Activision game for $40, he saw that he could be a hero and get eight games for the same money. Sales of new games went to near zero.

The game business went from being regarded as the big new thing to a burnt-out fad in just a few months. Did you think of giving up on making games?

DC: Hey, games are my life. The crash was unfortunate, and it was hard to weather. But there was never any doubt that the game business would approach the movie business in size. After all, a game is a movie with the addition of interaction.

The industry moved towards home computers after the crash, how did that affect game development?

DC: Activision was founded in 1979 with a five-year business plan. Home computers in their infancy had reached the market and they were certainly the wave of the future. Our plan was to make video games during the slow growth of the home computer and switch over to computers at some point in the future.

Our prediction showed video games rising and falling, crossing below the slowly growing home computer market by 1985. So we planned on phasing out video games and moving into home computer software at that crossover point.

Amazingly, in 1985 both businesses were right where we predicted. We had not foreseen the huge boom and bust of the video game, but after that dramatic surge they had settled in right where we expected. So a transition into computer games was always in the cards.

Once you make the transition into computer games, the hardware affects the game: Keyboard rather than joystick, sitting at a desk rather than on the floor of the living room, etc. In these ways and more, the hardware always affects the type of game one develops.

It seems to me that the industry focused more on 'hardcore' players after the crash and started producing more complex games.

DC: The hardcore gamer is always easier to reach than the casual player. We know what console he has. We know that he is willing to devote 30 hours or more to a game. We know we can get him to spend $60 to $80 on a piece of software.

The casual player is all over the map, including women who the video game business has never known how to reach. So there was a natural trend toward more and more complex games targeted to this hardcore.

I have never followed that thinking. I stick to games that a normal person can pick up easily and enjoy 10 minutes away from that difficult spreadsheet. I stick to casual games and that might be the secret to my longevity in this business.

Games seem to reach a much broader audience now, what do you think lies behind that?

DC: The casual market has always been there. The big players simply ignored it. It took online games like free adver-games to prove the market was there - Garry Kitchen and I pioneered adver-gaming with Skyworks, starting in 1995. It is now widely accepted that the casual gaming market is several times larger than the hardcore videogame business.

The amazing thing is how this brings us full circle. The games I designed at Activision and Atari were intended for the whole family. Kids played with dads on the family TV in the living room. I have been making casual games for over 30 years, and now it is trendy again.

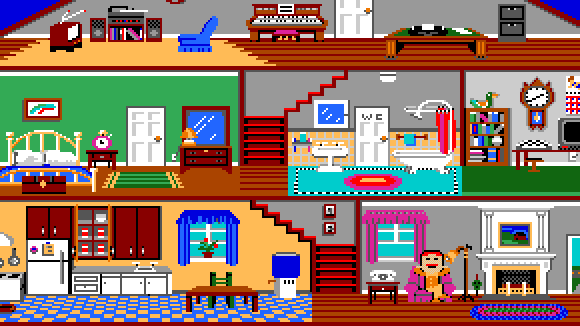

Going back to your Activision days, how did your computer game Little Computer People differ from Pet Person, the original version that Activision bought from Rich Gold?

DC: Pet Person came to us virtually bankrupt. The idea of doing the computer-based Pet Rock was a grand one, but the original Pet Rock cost nothing. It made money by wrapping marketing around a product of zero cost. Pet Person was hundreds of thousands of dollars into development, and it wasn't finished.

I came to the conclusion that as a non-interactive fishbowl it couldn't recoup its costs, so I added two-way interactivity. Now you could have an artificial life form that even communicated back to you. I am proud of the result. Unfortunately with nearly a year of my time added to the initial development costs, the product didn't make money. If it had, we had hundreds of plans for newer and better versions.

What was the reaction to Little Computer People on release?

DC: The marketing wrapped around the product was really good. It was fun to think of the little guy as pre-existing in your computer and simply being let out of the closet by the gift of a new house.

Some of the fun we had was staying in character with the concept in our interviews. So a question like "how many words are there in his English language parser?" would be answered: "What do you mean? He is alive. He can understand every word you type".

Those who 'got' the product were fanatics. We had a letter from a grandmother who bought two Commodores and two monitors so that her two grandchildren could each have a pet of their own when they came to visit.

The Commodore 64 also had an operating system bug that would damage the "brain" portion of the floppy disk one time in a thousand -- each little computer person's personality and status information was repeatedly saved to disk.

People got so distraught at the death of their person that I had to design a piece of "hospital" software for our consumer relations' department. You could send in your floppy and your little computer person could be resuscitated, complete with intact personality in most cases. As you can tell, the game had a small but very dedicated following.

Why did you leave Activision?

DC: I did not leave by choice. The new president, Bruce Davis, asked me to take a fraction of my salary, with the rest made up through an incentive bonus. I asked him to put the bonus in clear terms in writing and he couldn't. You might think we were at an impasse, but we weren't. He just slashed my salary without a compensating bonus. So I left. See, I learned something from my days at Atari when it comes to verbal promises.

What game of yours is your favourite and why?

DC: I have recently finished my 67th and 68th commercial games [the interview took place on 8th July 2009]: Arcade Bowling, a Skee Ball like game, and Ten Pin Championship Bowling; both for the iPhone. So a list of the things I am proud of creating would fill a book.

I invented a real cool technical trick to scroll the cars in Grand Prix smoothly on and off the screen. In Pitfall!, the swinging vine was a challenge, and I defined the game's screen layout algorithmically so that 255 screens could be defined in about 14 bytes.

Time and time again I have figured out ways to make a game console do things not intended by the hardware designers. So there is no one game that I would call out as my favourite. There are really too many for that. But each one gives me enough pleasure to ensure that I will do another.

That is in part why I have been called the Charles Schulz of video games. Charles Schulz lived in the world of his characters, and in some ways so do I, but the main comparison is in longevity. He drew the Peanuts characters for 50 years before his death. I am well over the 30-year mark and still doing it every day. And I will try to do so as long as people continue to enjoy my work.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like