Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Charting the meteoric rise of newspaper games, from Wordle to Pile-Up Poker and beyond.

One of video games' biggest recent success stories involves Wordle, a once-per-day word guessing game developed by software engineer Josh Wardle for him and his partner to play. It has a simple interface, is easy to understand, features no ads, and is free to play. Guess a five-letter word in six tries, come back the next day for another. So when it was released in October 2021 during the COVID-19 pandemic, it caught on very quickly.

Just a few months later, The New York Times bought it for a price "in the low seven figures." A few years later, it's still a gigantic hit, having been played more than 4.8 billion times in 2023 alone. It's so big that when the organization's tech union went on strike in November 2024, workers made versions of its games, including Wordle, that users could play instead of crossing the picket line.

Wordle's massive popularity is just one inflection point in the history of newspaper games—typically word or number puzzles, crosswords, Sudoku, and other games you play once per day. These kinds of games have been popular for over a century, and almost every mainstream subscription publication you can think of has their own.

via New York Times

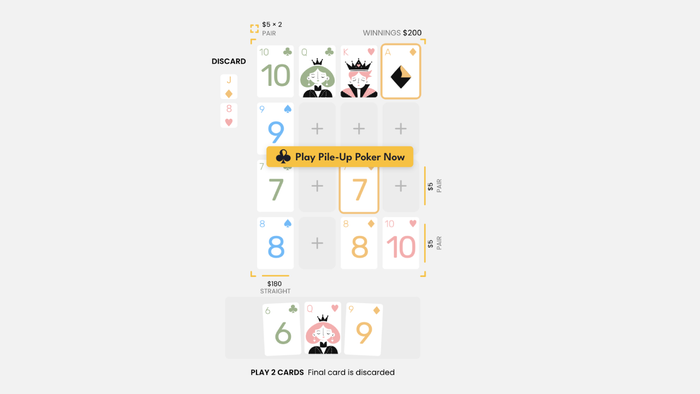

But there was something about Wordle that made publications and platforms take notice. LinkedIn launched three "thinking-oriented games" in May 2024, while Vulture unveiled Cinematrix, a grid-based movie trivia guessing game, in February. Subscription-based games platform Puzzmo launched in late 2023, offering standard fare like crosswords along with experimental endeavors like Pile-Up Poker, an oddly satisfying and challenging combination of poker and Sudoku. It was acquired by Hearst Newspapers a couple months later, and can be played across multiple websites like the San Francisco Chronicle.

Wardle says Wordle’s success is tied to its simplicity. "I think people kind of appreciate that there’s this thing online that’s just fun,” he told the New York Times. "It's something that encourages you to spend three minutes a day… Like, it doesn’t want any more of your time than that."

Experts interviewed for this article agree on this… to a point. Wordle is a simple yet effective game that appeals to almost everyone. However, it also benefited from great timing, releasing during a pandemic where people were aching for community in a world where building it felt impossible, and showed what still needed to be done to push daily games to the next level. It was time for a change.

The leader in the newspaper games space is undoubtedly the New York Times. Its crossword is one of the most well known, and puzzle editor Will Shortz might be as close to a household name as puzzle editors get. It was already a huge draw before the publication bought Wordle, and has become even more important in the age of digital subscriptions.

As traditional publications struggle with subscriber counts and making a profit, the New York Times has increased its numbers almost every year since 2014. This is thanks in part to a bundle that costs $25 per month and packs in subscriptions for both its games app and the paper itself. Its investment into Wordle is just one part of its growth strategy. As of November 2023, it had around 100 team members—up from around a dozen over the past decade—and has since hired more in community and design. “The half joke that is repeated internally is that The New York Times is now a gaming company that also happens to offer news," one anonymous staffer told Vanity Fair.

You'd be forgiven for wanting to call the New York Times a gaming company. According to Semafor, the NYT Games app was downloaded more than 10 million times in 2023. But despite this success and growth, Times executive editor Joseph Kahn maintains it's not looking to create a games studio, telling Vanity Fair that the company is not "Activision, and I don’t think we’re looking to become that." "These are brainteaser games for smart people who want a challenge in the course of the day. So I see them as very complementary, but not replacement, products for a news organization."

The New York Times is very much a media organization first, but since buying Wordle, it's launched Connections, which requires players to find four groups of words among 16 new ones each day. Semafor reports that it's been played around 2.3 billion times. It also released Strands, a game inspired by word searches, and is currently testing Zorse, a phrase guessing game.

"It’s undeniable that Wordle was a big tipping point for us,” chief product officer Alex Hardiman told Vanity Fair. But “it’s not Wordle only. It’s Wordle driving more attention to other games, allowing us to invest more in games.”

Wordle's massive popularity isn't the only reason for the rise in daily games. It was also spurred on in part by the pandemic, where people stuck inside with little to do were looking for a bit of routine to fill their day. Video game popularity and sales surged during the pandemic, with even the World Health Organization encouraging people to play games during lockdown. Wordle capitalized on that by being one of those tiny daily tasks. You solve one puzzle per day, and you're locked out until the next.

Stella Zawistowski, a puzzle constructor for Vulture, the New Yorker, and other publications, says that the pandemic "accelerated" the daily games space because people were looking for something that "makes you feel a little smarter." Wordle also had a secret weapon: a feature that automatically created a colored grid of your results that you could copy onto Twitter/X or a group message.

"I don't think [Wordle] would have been successful if you could just play as many times as you want every day," Zawistowski said. "I don't think it would have been nearly as successful if you couldn't post your score on Insta, on Twitter, on Facebook because then it gets people talking about it."

That community building is one of video games' greatest strengths, and that's all the more relevant with daily games. The New York Times has been slowly building up community, adding stats to its games and allowing people to join forums (although they're mostly just links to comment sections), but its success is often in spite of its lack of features. So many people play New York Times games, and there are a lot of chances to go viral. For example, Connections has become a viral hit in certain circles thanks to the chaotic nature of some of the solutions (a long running joke about how users see editor Wyna Liu as their nemesis has been the subject of many TikToks and memes). That's why Puzzmo co-creator Zach Gage believes that it doesn't have a lot to offer for many online players.

"Their platform is terrible," Gage said. "It's terrible in the sense that it is non-existent. Their platform is a website with a bunch of links to games, and then you go and play the games, and the games don't really interact with that website where you started."

Gage noted that during the pandemic, he noticed that his wife was playing Words with Friends, a mobile, multiplayer version of Scrabble, with family through multiple group chats. I see something similar among people who play Wordle. Even in 2024, I know people in group chats that are specifically for sharing Wordle results.

"If this was any other game that was big, there would be a social space that was connected to this game that everybody would just be able to enjoy… Why isn't there a social space for players like that?" Gage said.

Via Puzzmo

Gage, known for daily games like Really Bad Chess and SpellTower, launched Puzzmo in 2023 with engineer Orta Therox not only as a place to house his games, but to fill a gap that the New York Times left behind in terms of community building. There are leaderboards, social features like friend requests, easy access to a Discord server where players and constructors gather, and daily announcements discussing how well people did on puzzles.

Even LinkedIn noted the potential for games to connect people as its reasoning for adding daily games to its platform. You play one of the three four available at the time of this writing—Pinpoint, Queens, or Crossclimb—then see which of your connections have played. You can also then head over to leaderboards or immediately hop into the official post to talk with other people. It's barebones, but it works as a little push to socialize over its games. "You share your knowledge and get knowledge back, you share your experiences and hear about others’ own roads. And with games, you finish a puzzle and then talk about it with colleagues, friends, and distant connections," editor in chief and VP at LinkedIn said in the games announcement.

It makes sense that the New York Times would be the market leader in the daily games space just due to age and brand recognition—it debuted in 1942, so it's had the time to build up a name for itself. But it's been making changes to keep it up to date for 2024. It's fallen behind in regards to community building, but it's been working on its reputation for being stodgy, traditional, highbrow, and almost completely inaccessible. The only way to get good at a New York Times crossword isn't to know random trivia, but to do them over and over again so you start learning the answers to favorite clues and notice patterns.

There are better ways to do this, if you want them. A priority for Puzzmo was to provide multiple difficulty experiences in one app. If you want to solve a crossword without any hints, you can. If you want to go for some extra sidequests in Pile-Up Poker and engage further with a game's mechanics, you can do that as well.

Via Puzzmo

"One thing I've noticed is The New York Times tends to target either super high-end players or super low-end players," Gage said. "Their crossword is not very approachable for people who've never played a crossword, and their game Tiles is not very interesting for people who are really deep into games and want a deep experience… In Puzzmo, our focus is on building games that work for anybody."

Puzzle constructor Brooke Husic leads the Puzzmo crossword, which is a great example of this balancing act. Puzzmo crosswords vary in terms of difficulty, but that's not defined by the obtuseness of the clues. The crossword allows you to use multiple hints before revealing the answer, and

"We want somebody who's like, we have some of the best speed solvers in the world solving [the crossword] every day. And I want them to be there. I really want them to be there," Husic said. "But at the same time, I want someone who's never solved a crossroad before to go to post about any day and have it be their first crossword, and have a good experience."

The New York Times, for what it's worth, has been making changes to increase the accessibility of its puzzles, specifically its crossword. Everdeen Mason became the newspaper's first editorial director of games in 2021, and she told Vanity Fair that while the Times had to maintain the difficulty it's known for, it wants to be more accessible for newer players. "If we’re asking people to pay for a product that’s primarily this thing that they can’t access, then that’s not very smart," she said.

Beyond the sheer amount of thematic variety out there that lets players choose which crosswords or games they might prefer, a more diverse array of constructors and editors have also been behind some of the most well-known puzzle sections. The New York Times is no longer run by purely white men; Mason is a black woman who dyes her hair, wears anime shirts in interviews, and immediately wanted to challenge the team and "get people out of their comfort zones" with a Black History Month theme and more freelance constructors of different backgrounds.

Zawistowski has written before about how crosswords are mostly constructed by men, and began her career struggling against that establishment. "The partner I was working with was an older, retired, white guy, and so he would put Boomer references in his puzzles, and then I would have to clue them. It's just that's not who I am, whereas now I can put in the things that I love and then the puzzle feels more like me," Zawistowski said. But now, she's been able to stop freelancing in advertising and make puzzles full-time, and can make them on her terms.

Making puzzles feel more personal has been successful for Puzzmo. Husic ensures that crossword players have the chance to learn about the constructor and the process behind making that particular puzzle in notes that pop up after you've completed it.

"What was important to me was to make it very clear that humans made these, individuals made these and they cared so much about every choice," Husic said. It's a chance to engage with the player beyond just presenting a daily puzzle. "I have always wanted to exalt individual voices. Yeah, there's so many people who don't know that humans write crosswords. People think that computers are generating them, or they think Will Shortz writes every New York Times crossword."

Like with many fads and industries, there will be players who get tired and get interested in something else. The New York Times is invested in its games because of how much they do for the company, and it's hired dozens of staffers to get that done.

But daily games must continue innovating to stay relevant. Puzzmo releases new games all the time—most in an experimental, early access phase, and ropes in its audience for feedback. It also tries out twists on old formats. Crosswords typically fit inside a standard square grid thanks to old-school paper restraints, but Husic and the constructors literally think outside the box by playing around with the size and shape of the puzzles. "Puzzmo’s approach to grid design exemplifies its goals in bringing a human touch to games," wrote one intern back in August.

"There are, like, over 100 million people who are ready for the next Wordle game and will jump in and play it when it happens… that's the sort of thing that all these businesses that are looking into the space are looking at right now. They want to be the people who have that game when it happens, because it's going to happen," Gage said.

That's all expected. Industries ebb and flow, and the same will happen to daily games. But in the meantime, the daily games surge is providing new outlets for constructors and new ways to play. It's unclear if we'll ever get another Wordle, but the daily games space and its millions of players will be there when it's ready.

You May Also Like