Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

A comparison between the trading systems in Guild Wars 2 and its predecessor and how the two approaches can be synthesized to achieve a more ideal Trading Post that allows for both efficiency and merchant-ability.

Trading goods, resources, loot, and consumables is an integral part of the MMO genre. Not only does it facilitate a virtual economy, but it becomes a cornerstone of the game’s community. Entire guilds and clans are built on farming resources and loot, a vernacular of trading procedure is built by the players, habits and common practice are established, and players assign extrinsic value to items that have no inherent worth.

Because the buying and trading of virtual goods is such a vital part of loyal play and community building in an MMO environment, it’s a no-brainer that we as developers should put a marked effort into improving the experience for players. Most notable—to me personally—is the complete redesign of the trading system made between Arenanet’s Guild Wars and Guild Wars 2. For those who aren’t dogged fans of the franchise the way I am, I’ll give a recap of both systems before I dive into my suggestion for a healthy compromise.

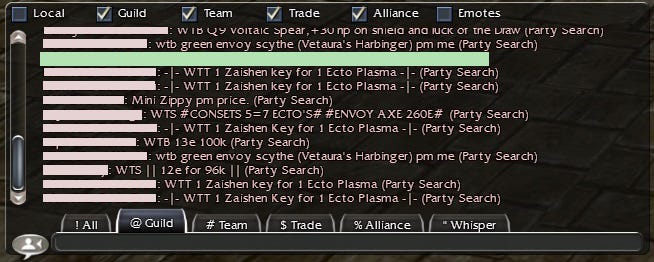

In Guild Wars, the best analogy I can think of for the trading system involves a large Italian family at a wedding. It’s clear that at one point there was an intended order and plan but somewhere along the way it got ditched in favor of a “Who can talk the loudest?” hierarchy. In Guild Wars (henceforth simply, GW) there was a trading system that hinged on the trading chat channel and the party search window that included a trade-specific component. There was no in-game mailing system between players that is common among competitors like World of Warcraft. The only method of trading was to somehow get the attention of another player who happened to have what you wanted or need what you were peddling. Certain inherent limiters helped to turn the experience into its final form. Because the trade channel was specific only to the outpost a player was in, the emergent behavior became for players who hoped to trade to gather in the biggest outposts so they could communicate with the largest possible audience. As the expansions released, larger towns were introduced and players would quickly migrate to the new location as the trading hub of the game.

Due to these huge congregations of buyers and sellers, if a player were serious about doing either of those things, they had to spam an advertisement in the local trade channel while simultaneously sifting through the trade window that only gave about a 1/3 snippet of each player’s ad. In this situation, the only way to be noticed was to be the "loudest" and most visible. Players would use an excessive amount of dashes and arrows to frame their adverts, switching to ALL CAPS, and spamming the channel, which would eventually lead the game to suppress them from posting further messages, drowning their chances for finding a trade even farther beneath the competitors.

Despite the logistical nightmare that it was, this system of trading lent the game a clear sense of community. I can’t stress enough that for all its faults, the GW trading “system” created a community of practice that encouraged being a good salesperson and cutting a deal. In other words, it allowed a lot of human elements in trading. If you could write a concise ad and talk up your customer, you could often make a better sale. If you were willing to accept various forms of payment (pure currency vs expensive crafting materials) you were more likely to find a buyer. Not only that, but these high-end crafting components became a sort of investment opportunity. Although their worth fluctuated, they were used as a stand-in for gold when the price exceeded the 100 platinum trading limit. If you invested in these materials at the right time or could find someone cutting a deal for a high quantity buy, you could sit on them until the prices went up again. But to avoid getting into the gritty economics details, I’ll summarize by saying that in GW, a player had to have personality, insight, and a bit of luck to be an effective trader on a regular basis. In essence, they had to be a merchant, not just a seller.

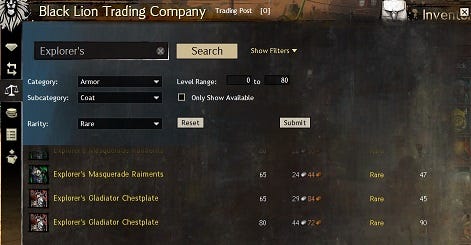

In GW2, the trading system made almost a full 180. Whether it was to improve the efficiency of trading for the player, to create a more streamlined economy, to funnel players into the gem store to spend real money, or a combination of the three, Arenanet replaced its criar-esque trading system with a back-end supported trading post behemoth. Several good things came of this, don’t let me fool you. Trading absolutely became more efficient for players. I’ve caught myself on more than one occasion singing its praises to the tune of “I love when gold just appears in my trading post pickups”. Without a doubt, it’s very easy to right-click your items, say “sell on trading post” (from anywhere in the world, I might add) and shove them off on the highest buyer, if you’re impatient, or align yourself with the lowest current selling price if you aren’t. Unfortunately, not only did Arenanet make trading easy, they made it spiritless.

In GW2 there is no player-to-player direct trading system. You can send mail to another player, but that doesn’t mandate a return mail. If you want to trade an item directly to another player, you’d better trust them to hold up their end of the deal. Otherwise, your only option is to feed your items to the Hungry Hungry Trading Post and wait for it to convert your stuff into cash. Effectively the trading system in GW2 has three distinct actions for both buyers and sellers: accept the going rate and buy/sell immediately, make a custom offer and wait for it to return, or wait for prices to change to something you like better. On the most basic level, the trading process was distilled to two binary options: “wait” and “act”. At no part of the process does a player engage personally with another. There is no bartering or negotiating to be had. You simply hand over your items to the system and accept what it gives you in return.

Stop me right here if I’m the only one who isn’t okay with that. I could be, but I really suspect that I’m not. I love the efficiency of the current system, but I believe there’s a way to have the efficiency and keep the soul of the trading process at the same time. So what are the strengths of both methods?

GW2’s Trading Post already tracks items based on name and metadata. A player can search for items by things such as rarity rating, type (weapon, armor, consumable), and other increasingly detailed information about each item. This part of the Trading Post Behemoth is likely its greatest strength. Storing metadata about each item makes it convenient for a player to find what they need. With this method, a player can better communicate to the system exactly what they want to know and the system is better equipped to return appropriate information. Where the Trading Post actually goes wrong is in believing that efficiency is always the end goal for a player. I’m reminded of a part of Ralph Koster’s article on auction houses in which he says, “Every time you make a design choice you are closing as many doors as you open”. Koster is arguing a similar point to mine—that efficiency isn’t always the end-all-be-all of good game design. To paraphrase a bit more of his article: games are comprised of challenges. Each challenge in your game is potentially enriching to a player. Challenges become a problem when they are outright inconveniences. If a player is posed a challenge, in this case buying and selling items, without having any personal development in return, it becomes only a headache. But the challenge of being a merchant rather than just a resource farmer who feeds all their materials to the trading post beast is an enriching challenge, so long as the system doesn’t impede the player’s ability to convey and receive information.

The system I propose allows each player to write an advertisement similarly to the way players in GW often did in the trade channel. Although instead of typing out quantities of items, they would use the system’s method of tagging. This way, each post contains a wealth of metadata about which and how many items are being sold by that player, while still allowing for a custom advertisement. As a seller, this allows a player to draw in a buyer based on the terms of his or her selling—things like accepting alternate currencies, discounts at bulk rates—and other things that can only be agreed upon when a middle-man system doesn’t exist. It allows both buyers and sellers to have the flexibility of a merchantable agreement. As a buyer, a player is capable of finding exactly the item they want thanks again to the wealth of back-end information provided by the existing game database. The player will be shown only ads containing the item they are searching with the added bonus of possibly stumbling upon something they didn’t know they wanted. While this system poses the player the new challenge of sifting through ads from sellers, it also adds the skill-building element of knowing a good deal from a bad one, the finesse of investing properly, and the determination to look through all options before settling for a price.

In this system, the advertisements would serve only as the face for a buyer or seller. Instead of simply throwing items into the trading post, the player would be capable of contacting the other party via whisper—private message—to make the actual terms of the deal and carry it out “in person” as was the custom in GW. Interacting with another player is one of the most important elements of the merchantability construct. The room for human decision is what lends soul to the trading process. Personal interaction is what separates the skilled from the unskilled when it comes to trading. In a fully automated trading post system, any monkey can farm an endless amount of expensive items and wait to sell them at the optimal hour based on price. In a true merchant market, players with skill and ability to assess what others want, and to compromise, will thrive. And in a system that requires a certain amount of skill, players ultimately feel more rewarded by their experience.

The core principle of MMOs is the interaction of players with one another. Removing that element from a mechanic as important to the longevity of a game as its economy is a mistake. Players constantly shape the world and community of any MMO and for any such game to remain meaningful, the players cannot be allowed to see each other through the eyes of the infallible trading post. To maintain a community, even an activity as comparatively mundane as trading must be conducted between two players, not between a player and a database. Bring back the merchants. Bring back that jerk that won’t accept anything less than going price. Bring back my ability to say “screw him” and find someone willing to cut me a deal. Bring back the personality.

Read more about:

BlogsYou May Also Like