Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Humanity producer Tetsuya Mizuguchi, designer Yugo Nakamura, and executive producer Mark MacDonald on the design philosophies behind the surreal, logic-bending puzzler.

This interview has been edited for clarity

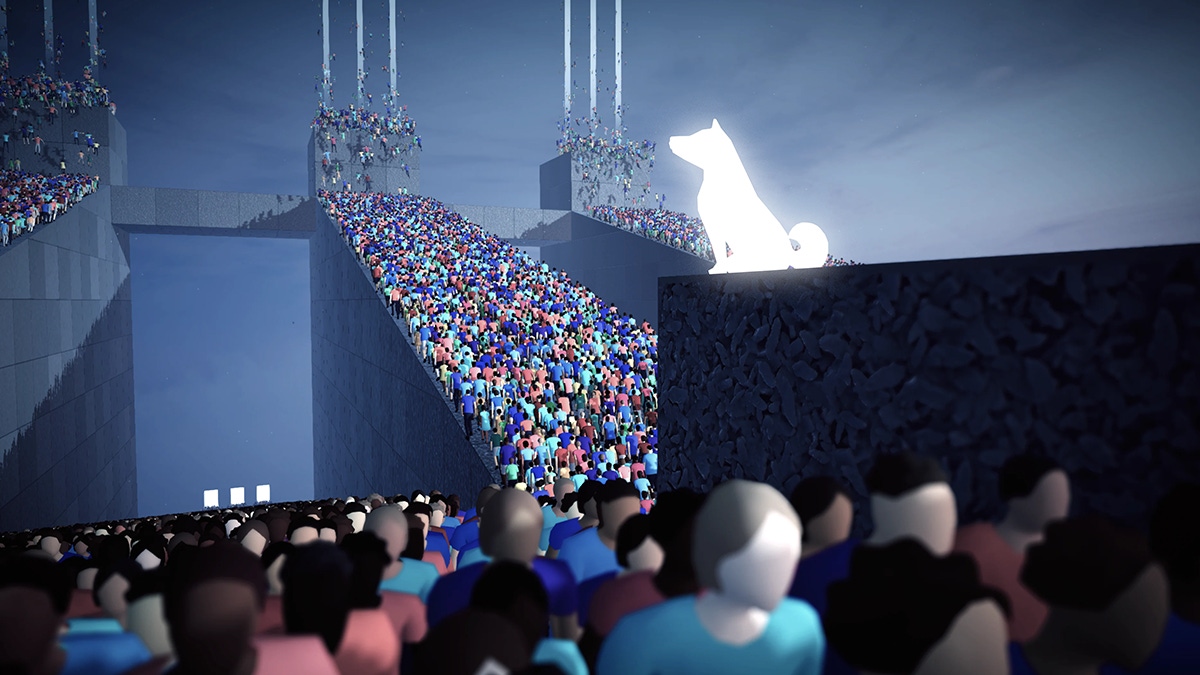

You are radiant. You are glowing. You are a dog.

To be more specific, you're a golden Shiba Inu that must guide an endless procession of souls towards the light at the very end of the world. It's pretty breezy at first. Just bark a few directional commands at your troupe of strangely obedient followers to steer them around a few rudimentary hurdles and you'll be a shoo-in for Employee of the Month.

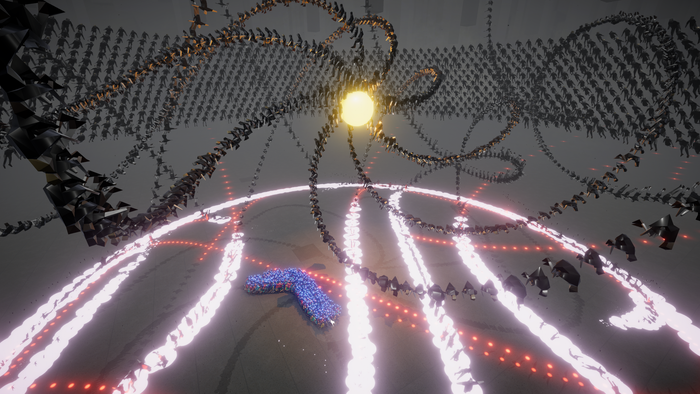

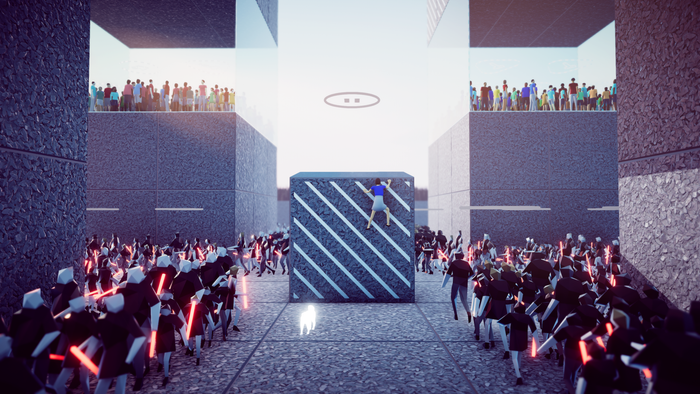

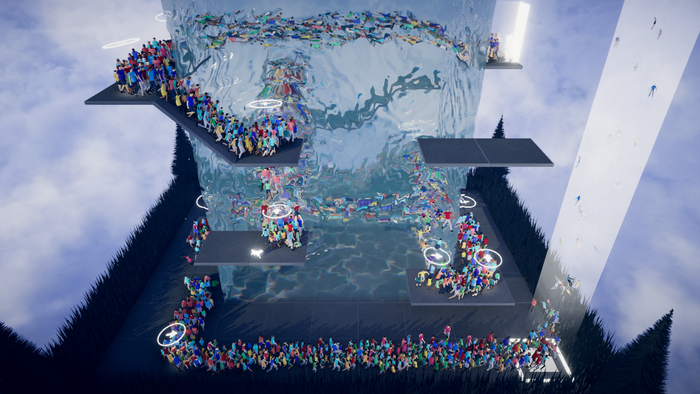

Much like its namesake, however, Humanity very quickly becomes a complex beast. Soon you'll be using a fluctuating compendium of absurd commands to overcome increasingly perilous obstacles (think bodies of water suspended in mid-air and hostile mobs) and create living Rube Goldberg machines that will make you believe in the power of omnipotence.

In truth, anybody who's already familiar with the talented teams behind Humanity would expect nothing less. The game is a collaboration between Tha Ltd, an interactive design studio based in Tokyo, and Enhance, the developer that gifted the world transcendental experiences like Tetris Effect, Lumines, and Rez.

The project first sprung into being when Tha founder Yugo Nakamura asked the question "how many digital people can we put on-screen at once?" In reaching for an answer, Nakamura created a tech demo that piqued the interest of Enhance founder and veteran designer Tetsuya Mizuguchi, who felt inexplicably drawn to the concept and Nakamura's search for something more.

"Yugo-san is highly respected and highly-regarded in his field of work. But he's not just a designer. He's been building experiences too. Knowing his background and the richness of his work, when I saw the demo I just felt there had to be something behind him putting all of those humans on screen. I thought [the demo] couldn't be the end of the story," explains Mizuguchi, speaking to Game Developer.

Mizuguchi says he wanted to help "equip" Nakamura with the right tools to turn that nascent tech demo into a cohesive experience, but he also notes it was his job to challenge the veteran creator to keep expanding and iterating on "the little thing I saw" all of those years ago.

Echoing the nature of the game itself, production relied heavily on trial-and-error and, sometimes, fractious collaboration. Discussing the broader creative philosophy that informs most of their work, Nakamura says they personally strive to impact people by making an immediate impression, but concedes it's an approach that might sometimes have been counterintuitive when attempting to turn a nebulous tech demo into something more lucid. "The more I stare into what I'm doing, the more I want to push it to the extreme. Because I think that's how I can maximize its impact," they say. "If I were to talk to you about humans falling, it might look and sound cruel, but I'm still going to pursue it because I want to make people feel something." Nakamura adds that development became something of a tug-of-war between themselves and Enhance, but lauds the studio and Mizuguchi for providing "balance."

Picking up that thread, Mizuguchi suggests the key ingredients were already in place, but that Enhance had to help Nakamura find the fun. For instance, he describes the Shiba character (a masterstroke that Nakamura simply "dropped in one day") as the "missing link" that helped bridge the gap between players and the puzzle stages, grounding them in Humanity's surreal world by giving them a (meta)physical presence. The myriad of commands (turn, float, jump, fight, split, and more) were also crucial to imbuing the moment-to-moment gameplay with more weight and urgency, facilitating some light platforming by asking players to manually place and remove each instruction on specific tiles within stages.

"We were like 'okay, we have these ingredients, but how do we assemble it to avoid the repetitiveness of playing a puzzle game?' Throughout that process we were performing this balancing act, but we were helped a lot by our user testing process," explains Mizuguchi. "It was layers upon layers of work, but we managed to trim the fat and create something, if I can say so myself, very sophisticated."

Humanity's conundrums take place across a sequence of brutalist stages that gradually introduce new threats, mechanics, and abilities. Some are mandatory and others are completely optional, but if you want to collect every single Goldy—imposing humanoid figures cast in that most opulent of metals—you'll need to unravel them all. It's a puzzling slalom that revels in making players feel impossibly dense before rewarding their persistence with dizzying, endorphin-inducing eureka moments.

The real beauty of Humanity is how gently it scales to ensure players never feel overwhelmed. Even at its most frustrating, you never feel cheated. Solidifying that progression curve required tireless iteration from both teams. As Nakamura explains, "level design is just really, really hard." Initially, Tha took the lead designing Humanity's stages but found the task to be near "impossible." Having reached an impasse, Nakamura called on Enhance for help, and the result was an array of stages capable of confounding the developers themselves.

For instance, there was one level in particular that left Nakamura dumbfounded to the point they assumed the issue was caused by a bug. So, they "fixed it" and informed the designer responsible, only to be shown a seemingly obvious solution that had been staring them in the face. "You've just got to shift your perspective," says Nakamura, "and then all the pieces come together."

It's good advice for players, but changing your viewpoint can be difficult when you're so close to a project. Mark MacDonald, an executive producer at Enhance, explains that while iteration is essential, tweaking just one level could "change the entire scope" of the game. Hammering home Mizuguchi's earlier comments, he reiterated that testing was worth its weight in gold to the dev team, because it allowed them to view the project through fresh eyes.

"We had to do so much testing because it's like hearing a joke a thousand times. You don't know if it's funny anymore. You no longer know how challenging a puzzle is," says MacDonald. "Different people also have different approaches to problem solving, so during testing we were able to differentiate between users who would appreciate the challenge more, who didn't want any hints, and people who are really quick to give up."

In thinking about how they might keep different players happy, the team incorporated features such as solution videos that can be accessed via the pause menu. They also chose to make some of the more fiddly stages optional, but used the allure of Goldys—which are needed to unlock bonus items and additional stages—to reel players in. The result is that people have the ability to control their own difficulty to a certain extent.

MacDonald notes that some levels also seemed to have a universal appeal, and so the team set about reverse engineering those fan favorites to see what made them tick. "One of the levels we point to a lot early on, which is in the demo and the final game, is called 'Loop the Loop' (note how each title also contains a hint). Early on we recognized that everybody likes that level," he continues, "so we sat down and took it apart piece by piece, and what came out of that process was a ton of knowledge.

"For example, with that level in particular, you really feel like you've learned something, which is the ability to make these little loops to keep switches flipped. It teaches you a new strategy, so there was an 'a-ha!' moment. Importantly, you knew that when you found the solution, there might be a way to subvert it [...] and kind of cheese the stage, but it was also obvious when you had cheesed the stage." Whether players solved that level the way the devs intended or "cheesed" their way to success didn't matter, because in both instances players needed to be "intentional." That, for MacDonald, was a crucial piece of the puzzle.

Harking back to the original tech demo that captured the imagination of Mizuguchi, the team felt it was important for players to connect with their gaggle of humans, but realized they couldn't pressure them to save each and every one. During my playthrough, there were times when I chose to sacrifice some of my cherished flock for the greater good, and while I took no pleasure in marching them into the abyss, seeing them dissolve into specks of eternal light before hitting the ground made me feel much better about the whole ordeal.

"There's no score that keeps track of how many people you're losing," says MacDonald. "This was an important thing for both Yugo-san and Miz. There's no clock ticking down, and no counter telling you how many souls you've lost." He adds that one of the "big things" the team hit on was that failure should be viewed as the pathway to success, and not a punishment. And it works. There's a sense of calm amid Humanity's chaos because there's an immediate understanding that some solutions require sacrifice.

"The point is to retry. That's why we make an effort to stress early on that the people aren't dying. They're intentionally not splatting on the floor. We spent a lot of time tuning the effect there and the message around that. Sure, as a human being you're going to feel something when people are being squished, and to some extent we want that, but we didn't want people to feel this terrible weight of responsibility." In short, the team needed to make people feel comfortable with leaving some unfortunate stragglers behind, whether that's because they were squished underneath a falling block or told to stomp endlessly around a switch. Did they succeed? Why don't you ask the 100 people I accidentally punted into a solid wall.

I know that sounds a lot like mass murder, but it's just a drop in the ocean where Humanity is concerned. Referencing Nakamura's determination to place as many humans on screen as possible, we ask if the team eventually reached a limit. "Because we do have a PS4 SKU and minimum spec PC SKU, it is something we're having to look at and analyze. I think most of the levels can accommodate up to 5,000 people, and I think there's one special level where that goes up to 10,000," says MacDonald, making me feel slightly better about some of my more costly experiments in the process.

Towards the end of our interview, we ask Nakamura how they felt about pivoting to full-fledged game development after working in the world of design. Rather candidly, they suggest they might not have made Humanity had they realized how much it would have demanded.

Comparing the two, Nakamura explains that when they're designing a website, for instance, they know when to stop. If they're happy and the client is happy, it's a case of mission accomplished. Making a game is rarely that simple. "Where is the bar? Where is the end point? I didn't know how far you needed to take it," says Nakamura. "I couldn't see the finish line, so there was just this continual feeling of stress and not knowing what the end goal was." He compares game development to exploring uncharted seas centuries ago, not knowing if you're going to hit land or simply tumble off the edge of the world.

"Even with the game coming out, I don't know if it's actually fun or whether it's hitting that bar. But Miz, Mark and the rest of the team worked to guide me along and almost became a satellite granting me a sense of direction." It might not have been smooth sailing, but Nakamura said that embarking upon this journey as a beginner and eventually charting a course to launch has given him a sense of fulfillment and satisfaction that's "indescribable."

As for Mizuguchi, leaning into his new role of a producer has allowed him to usher more new experiences into the world. They're not all related to video games, of course—he mentions a synesthesia suit and synesthesia "chair device" that he's also been working on—but he hopes that each one, Humanity included, will help users feel something.

"My mission and my goal has always been to integrate this synesthesia theme and element into an experience," he says. "I can with confidence say that this is my life's work, and I'm spending every ounce of energy I have in order to put these experiences out there. [...] But each experience I put out also becomes part of a larger loop that expands even further as technology advances.

"I've found my joy in making and discovering those experiences. Tetris Effect is a great example of all those elements coming together, but what I know is that technology will only help us expand the range of the emotional journey [we can take people on]. I can only do so much, though. I can only make so many experiences while I'm around, so I've surrounded myself with people that feel that same sense of direction and potential and possibility. That's what drives me. That loop is what keeps me going."

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like