Paladin's Quest (AKA “Lennus: Memory of the Ancient Machine”) is an RPG for the SNES, developed by Copya Systems, directed by Hidenori Shibao, and published in 1992 in Japan (1993 in the US).

Paladin's Quest (PQ) was experimental, remains largely unknown, and was difficult for many people to connect with. However, I think it is worth taking a closer look, especially at how the visuals help to create an engaging and interesting world.

WORLDVIEW: Destruction and decay of a never-before-seen world.

After looking through blogs and forums, I discovered that many people described the experience of playing PQ as a strangely enjoyable feeling of alienation within a haunting and totally foreign world. I felt the same way, and the director, Hidenori Shibao, confirmed that this was the basic idea for the worldview of the game.

Let’s take a look at how each of the following five elements help to establish and support the worldview. At the end I'll focus on shortcomings and areas that hold the game back.

RULES & GOALS

The structure and rules are standard for a Japanese RPG: gain levels and grow stronger as you progress on a linear journey through a fantasy world, gaining allies, reaching new towns, and beating bosses until you finally confront the "Final Boss" and save the world. PQ sets itself apart, however, with its equipment and HP systems.

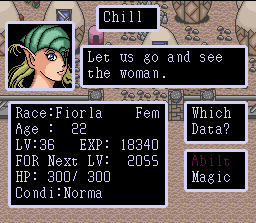

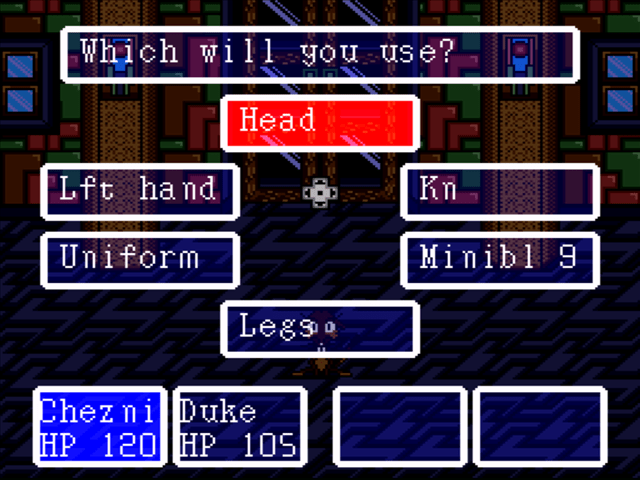

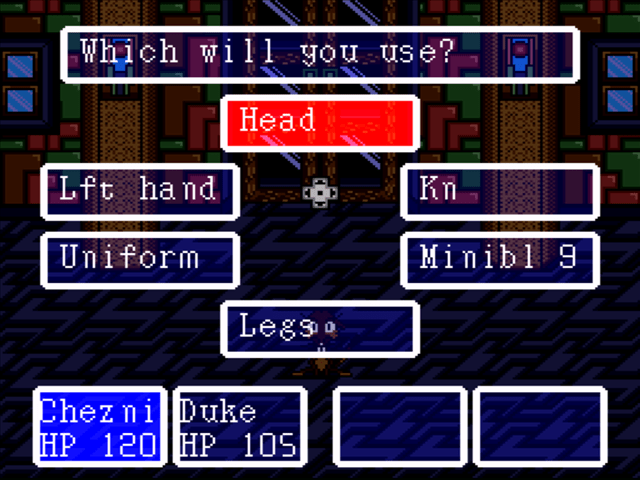

In addition to two required characters, there are a large number of optionally recruitable mercenaries. In most games the player can buy new weapons and otherwise change a character's equipment, but in PQ each mercenary's weapons, armor, and spells are permanent. However, rather than being limited to attacking with their weapon, characters can attack with their head, feet, belt, or body in battle (or whatever is equipped there), sometimes with unexpected effects.

The variety of abilities within their permanent set-up gives each mercenary a unique feel and play style- an impressive accomplishment given how many mercenaries there are. The sense of surprise and discovery that comes along with finding a new one and testing their abilities and equipment also builds on the game’s theme of exploration of a new world.

PQ innovated further with its Hit Points (HP) System. There are no Magic Points (MP)- all magic spells cost HP to cast. In addition, healing items (in the form of belts full of healing bottles) are quite rare. To make up for this, characters have a lot of HP and don't need to be healed multiple times after every battle; rather, the player must use their few healing bottles intermittently and strategically.

In this way, coming upon a new "belt" is a major discovery, and a source of excitement and relief. The HP System, belts, and bottles allow the player to focus on dungeon-exploring and battle without the distraction of constant HP recovery, in addition to contributing to the game’s refreshing novelty.

VISUALS

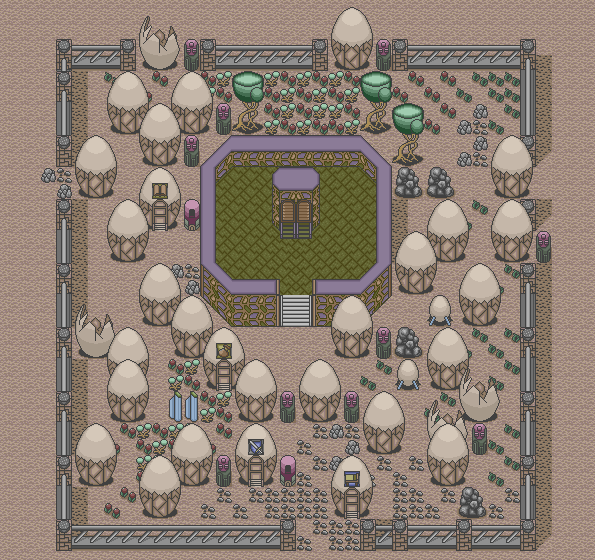

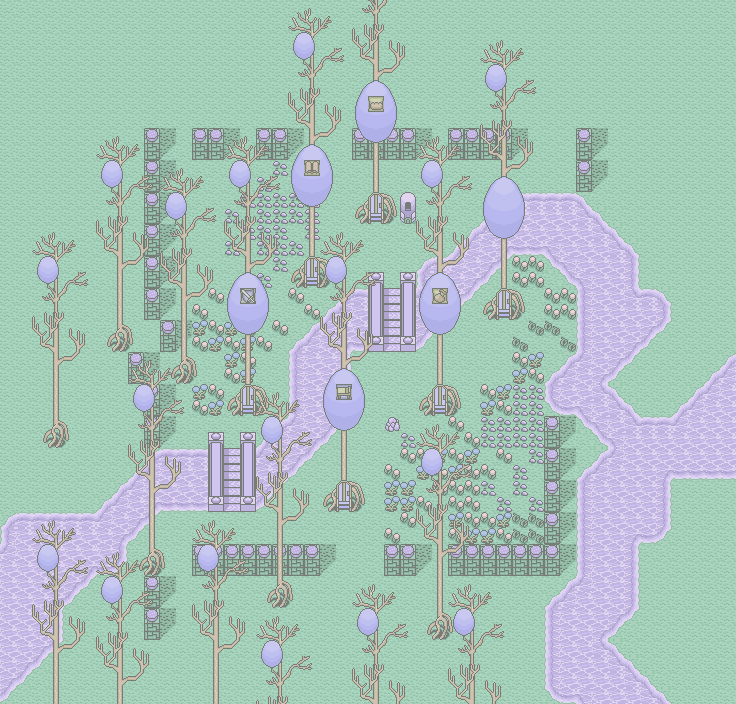

PQ shows considerable imagination and creativity in the designs of the buildings, flora and fauna, geography, and races that populate it. However, rather than being randomly thrown together solely for the sake of novelty, they are arranged deliberately to develop the worldview through consistency and contrast.

The division of the game world into a colorful, pastel Northern continent and a dark, drab Southern continent creates the central contrast of the game. Within these two areas, little explanation is provided for why things look the way they do or what their purpose is; however, thematic consistency and repetition make the game world feel like it has its own internal logic.

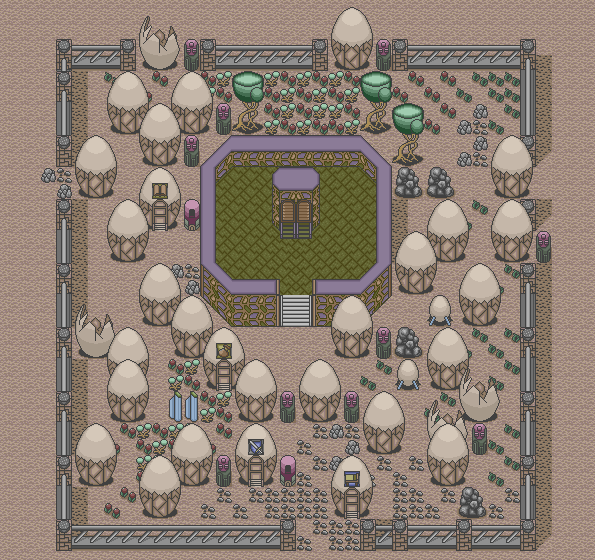

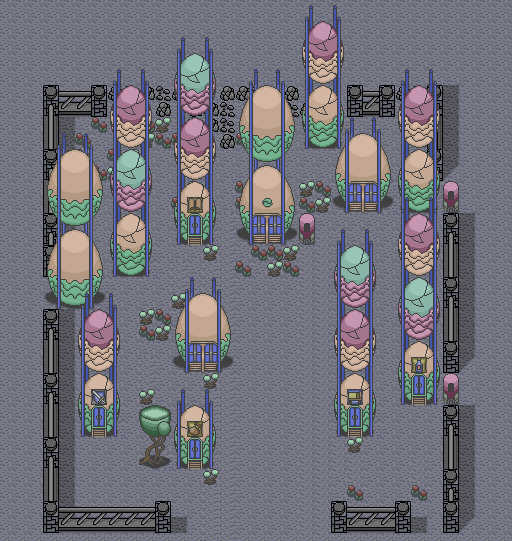

On the Southern continent, for example, the buildings are shaped like eggs, each town with its own variation. This thematic consistency gives the South its own style, sharply different from that of the North, while at the same time maintaining a sense of surprise upon discovering each new town’s unique take on the egg theme.

Conshiuto

“Conshiuto”

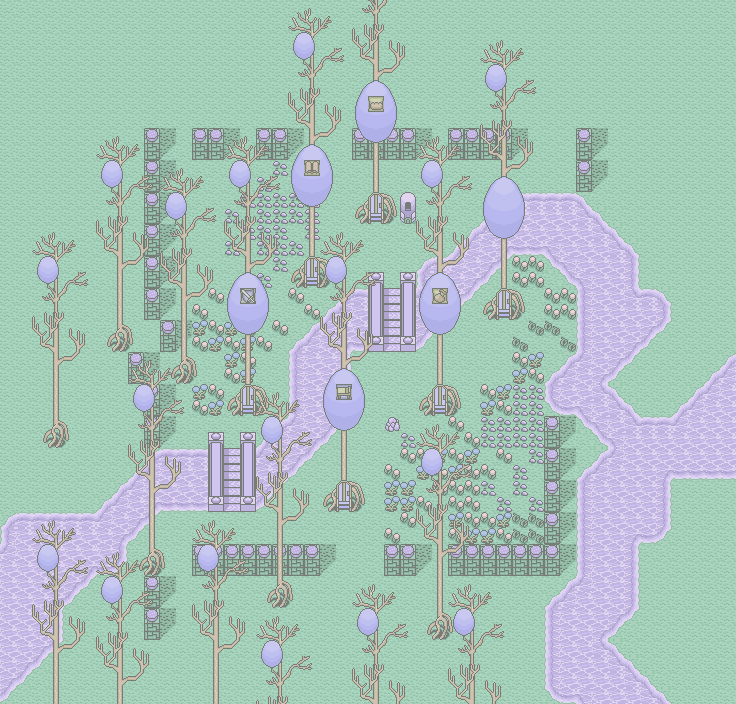

Misuto

“Misuto”

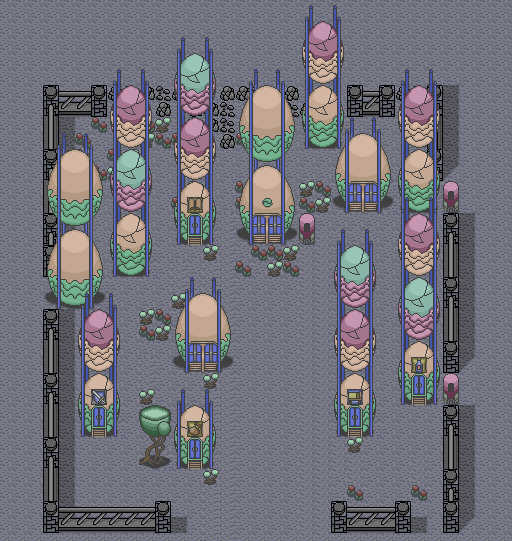

Roki

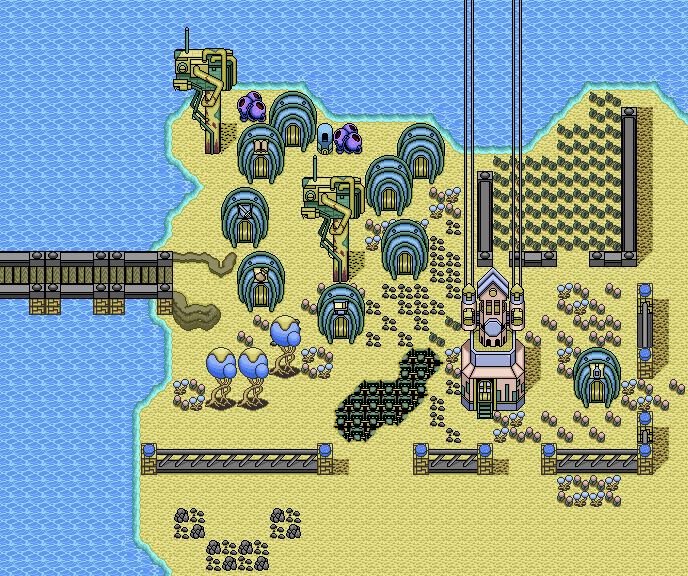

“Roki”There are also a number of unexplained mechanical-looking structures in what is otherwise a fantasy world of magic. Given the beginning of the game, where *SPOILERS* the main character accidentally uses an ancient machine to massacre his town (hence the game’s title), the odd mechanical structures serve as an ominous reminder of these events and hint at powerful, forgotten technology.

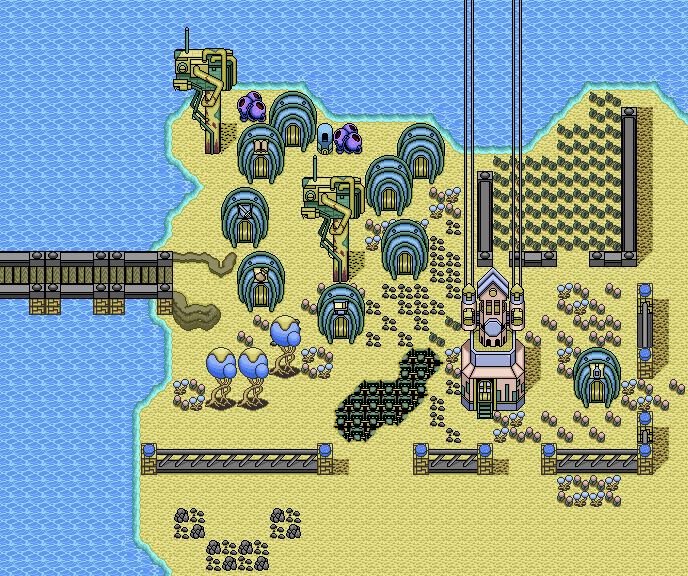

Ratsurk

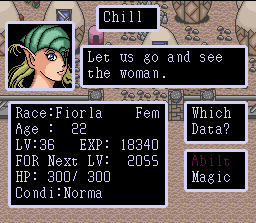

“Ratsurk”The colors used in the game’s environments also lend themselves to the themes of sadness and destruction. For example, purple, blue, and yellow are usually associated with decay or injury, yet these colors dominate the life and landscapes of PQ.TEXTMercenary characters have little to no dialogue, but each does have a one-line introduction on their stat screen that adds bits of story and emotion to the game-world. The unusual names of the races, characters and the towns also add to the player's journeys through an alien world.

Chill

Chill the 22-year-old Fiorla wants to see the woman!In addition, dialogue with townsfolk helps build storysense; people on the Southern continent, where the latter half of the game is spent, are generally unfriendly, saying that everyone from the North smells bad, for example, including your characters. Since townspeople in most RPGs are consistently passive and friendly, it is shocking to spend a good part of PQ in this inhospitable environment and adds to the feeling of alienation in a strange land.SOUNDWritten by Kohei Tanaka, the soundtrack is considered one of the greatest of its time, and some songs were included in the Tokyo Philharmonic Orchestra's concert of arranged video game music. Most of the songs are ominous, somber, and haunting (my favorites are "Red Earth, Dark Hearts,” “Memory of Raiga,” and “Deep-Rooted Hatred,” which you can listen to here). Given this, the basic town song stands out for its relaxing, positive feel. Aptly titled “Momentary Peace,” it captures a sense of "I've been out exploring in a spooky alien world, but now I’m safely back in town."Sound effects provide another strangely sad touch- when you open an item box, for example, rather than a fanfare or flourish, a short mechanical note plays, followed by a sad, downing note when the box closes. The sound effects for weapons in battle are sometimes unusual to the point of making one wonder if there was a mistake during programming; they don't always match the type of weapon being used, but even this adds to the game-world’s alien feel.CONTROLSThe controls are standard with the exception of the menus, which can be navigated solely with the arrow keys. This is surprisingly satisfying, thanks in part to being able to attack with all parts of the body: pressing “up” lets you attack with the head/helmet; “down” with the feet; and on the left and right you can select each arm, the body, or an accessory.The menu windows themselves are relatively unobstructive. In battle, they are transparent so that enemies are still visible behind them, and the main menus outside battle, while opaque, are small and displayed as an overlay on the current screen so that you can still see the characters and environment in the background. This keeps the player "in the game world" where the rest of the action happens, rather than transporting them to a separate screen of menus as many games do.

Chezni

Chezni attacks with his headWHAT COULD BE BETTEROne problem with the permanent equipment system is that early mercenaries become painfully outdated later in the game, encouraging the player to drop them in favor of new, far more powerful characters. For example, a favorite mercenary of mine was the martial artist named Dan, who ends up being weak later in the game due to lacking spells or powerful equipment. When it came to the final boss, he was completely ineffective.Successfully creating a character that the player likes and wants to use is a major accomplishment for any video game, so I think games should encourage and reward this rather than punishing players for feeling a connection to a character. Many games with a large number of characters make this mistake, and PQ is no exception.PQ also suffers from translation problems. Due to character limits, many spell and item names are drastically shortened to the point of being incomprehensible, and the dialogue is sometimes awkward. Personally, these kind of problems don't bother me much- who knows what "G Milk" is, but I'm willing to try it and discover that it raises my character's "Power." Again, though a bit extreme, this contributes to the world’s feeling foreign and strange.Though the basic layout of the menus is an interesting way to keep the player in the game world, navigation on the main menu is quite cumbersome (you must re-equip each body part in succession whenever you want to change a single piece of equipment, for example), and ends up wasting time and causing frustration.Perhaps a little more detail, depth, or better quality writing in PQ could've added to the feeling that these strange places and faces have tangible meaning and are part of a larger world in motion. Admittedly, the game relies heavily on the player’s imagination and willingness to just “go along with it.”SUMMARYRules & Goals: Standard for Japanese RPGs, but with a unique twist on characters’ equipment and the HP system, which help streamline battle and give each character a unique feel.Visuals: Alien in everything from color scheme to the shapes of plants and structures. Uses consistent visual themes with simple and imaginative graphics to develop the worldview.Text: Townspeople’s lines, minimal character descriptions, and unusual names of people, places, and items add to the foreign-ness and storysense.Sound: Haunting and ominous, it's considered one of greatest scores of the SNES-era and was included in the Tokyo Philharmonic Orchestra's album of arranged video game music.Controls: Standard for Japanese RPGs, but with a novel approach to menu navigation.Though PQ’s basic structure is conventional, it uses originality and novelty to create a colorful, never-before-seen alien world with a haunting atmosphere. It's worth experiencing, at least as an example of what can be done when imagination is applied to every element of a game in order to create a strong worldview.