Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

The director of cult hit Deadly Premonition explains the twisted genesis of the game among the ruins of a cancelled project -- and how, in the process, he found his chance to realize ideas he'd been nursing for his entire career.

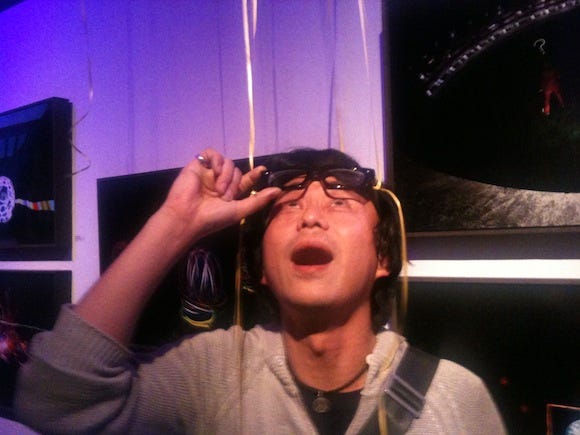

There's something about SWERY.

There's something about the broken English in his tweets, in his love of American B-movies, his extreme caffeine addiction, and in the way he got so excited when I introduced him to Out of this World creator Eric Chahi at a party that he accidentally spat on his face.

SWERY (or Hidetaka Suehiro, if you want to get formal about it) is a character for sure, which made him something of a media darling when his open world occult mystery adventure Deadly Premonition came out in 2010.

It was perhaps one of the more polarizing games of this generation: On the Metacritic scale, Destructoid gave it a 100. IGN gave it a 20. (I gave it a B... that particular outlet didn't score numerically).

But the game -- a clear Twin Peaks homage with an unreliable narrator that spoke to an imaginary friend, a town full of inhabitants that wore gas masks and carried around casseroles, and a shaving and washing mechanic that would punish you and call you a "Stinky Agent" if you didn't participate -- was hard to ignore.

Many of those who vocalized their love of the game (including the game's publisher, Ignition) focused on its absurdity of the dialogue, the oddly chipper music, or the PlayStation 2-at-best graphics. The majority of the praise was just about how damned weird the game was, but there's more to Deadly Premonition. Under its surrealist exterior (and fairly awful, unnecessary combat mechanics) lies a brilliantly designed interactive narrative that left players actually wanting to engross themselves in the story of what was, on the surface, a silly zombie game.

SWERY is a gifted designer, and Deadly Premonition introduced a lot of fresh ideas that most of us ignored.

Now that a Director's Cut version of the game is on its way, I thought the time was right to revisit this previously-unpublished interview I conducted with SWERY at the 2011 Game Developers Conference, just before his rather inspiring Game Design in the Coffee lecture (click for video!)

You have a set of game design rules, one of which is "Freedom in gameplay is the freedom of timing." What do you mean by that?

Hidetaka Suehiro: When people talk about freedom in game design, freedom is considered choices for the player. And when you're creating a storyline, sometimes it means side quests, and other times it might mean having multiple endings.

But when I was thinking about the freedom that we wanted to put in Deadly Premonition, I didn't think that would be quite enough. I was aiming to create this stronger sense of freedom that the gamer might be able to attain by doing something else.

In normal games you're told what to do, and you're given a challenge to do that, and then the game tells you if you did good or not. And if you did good, you get to move on in the storyline. For Deadly Premonition, I wanted to put a twist into that flow. I wanted to make a small little change in that, so that we have an extra branch there.

At first you're told what the quest is about, and then from there you're given this choice of whether you want to take on that quest, or if you want to do something else. Normal games would probably find a way to... not scold the player, but try to force the player back onto the rails, so that the player sticks to that challenge. But for Deadly Premonition, I wanted to allow the player to decide that, "Hey, I don't want to do this right now. I want to do this later, so I'll go do something else."

So that's why the game forgives you for missing scheduled appointments, letting you try again the next [in-game] day?

HS: That's right. As a creator, by doing this, I'm allowing the player to have a stronger sense of freedom. Then at the same time, in his mind, somewhere unconsciously or consciously, the player is becoming more willing to play along with the story. So when I reach a point in the storyline where I need to have the players play a certain element of the game, then they're more willing to take part in that.

When you complete side missions in Deadly Premonition, your reward isn't necessarily an item or a goodie in the game. The reward is often just more dialog and more story, and more depth to the characters. It struck me that the game was rewarding the kind of player interested in learning more about the world. I'm wondering if that was an intentional design decision?

HS: It's intentional. In other kinds of games, when you finish one part of your missions, most of the time you just get access to other areas. You get to go to another island or village or whatever. But in Deadly Premonition, I wanted to make your rewards come inwards, not outwards. So the rewards would be to get to know more of [the game's fictional town of] Greenvale, and its inhabitants.

So with more knowledge of what's going on in the town, or more knowledge of the people that you're interacting with in the game, you become fond of the people in this small town. So the reward is not just about hearing more dialog, it's also intended so that the player would feel more comfortable within the city.

Was it difficult to balance the game so that players who just wanted to plow through the main story without hanging out with its characters could do so, and still have a satisfactory story?

HS: I was very confident that the main storyline would be a very satisfactory and cool story in itself. The side quests were designed so that you get more detail about what's going on in the town. For people like you, who would go and talk to everybody in the town, you would get more information about the things that are going on in the town and hopefully, by design, we were trying to tickle you into wanting to talk about the game to other people. It's a small little tactic, a little technique that was experimental that we put into the game.

It's cleverly done. It's very effective.

HS: I wasn't totally sure that this would work. So when we implemented that spec, that part of the game, I wasn't totally sure it would work or not. So it's good to hear that.

When the townspeople go about their daily business and do things independently of you, it reminded me Sega's Shenmue. Is that where the inspiration for that came from?

HS: I only played that game for about 30 minutes, so it's hard to say if I was influenced by it. I think I was more influenced by real-time strategy games, where even if you let go of the controller you still see things going on.

Of the three games you've directed, I'd say Deadly Premonition is your first story-based game, where you're directly interacting with the story and influencing its events. Certainly Spy Fiction and Extermination had a narrative, but it seemed separate from the gameplay.

HS: When players finish my games, I want the player to be surprised. I want them to have something that lingers with them. With Spy Fiction, there was this little thing where we made it so that the gamer would have to finish the game twice in order to see the real ending. It was just the way the game was designed; the rails were very strict in that regard. There was no freedom of timing. In Deadly Premonition, after looking back on Spy Fiction, I thought maybe we can relax those rails a bit and see what we can do there.

The freedom of timing really gelled well with having [Deadly Premonition protagonist] York and [the voice in his head] Zach agreeing to solve the crime at their own pace. They're not in a big rush. If you decide to not do something now, you have Zach agreeing, saying, "We don't have to do this right now; we can do this tomorrow."

Let's talk about your career. When did you start in game development?

HS: I believe it was 1996.

You were doing what in 1996? How did you start?

HS: I was at SNK. The first project they gave me was a game called Kizuna Encounter. I got to work on the main character's collision and some of the AI adjustments for that character.

How did you get there? Were you seeking a career in video games?

HS: At first, when I was studying in school, I wanted to make movies. That kind of evolved into wanting to make CG animations, working on commercials and stuff. And after a while that evolved into me wanting to actually control that character that was on the screen. So I started looking for jobs at game companies. I ended up working at the company that was closest to my home, and that was SNK.

Did you play games before that?

HS: Yes. I was a gamer. I owned a Nintendo. But even before that, my father owned a PC, so I was playing simpler games before that.

Was there a particular game that you played that made you realize that video games were an effective means of telling a compelling story?

HS: In regards to stories in games, I was very impressed with Goichi Suda's Flower, Sun and Rain and Hideo Kojima's Policenauts.

When you started at SNK, you said that you wanted to control your characters and animation on screen, rather than just animate them. Was there a sense of satisfaction working on the Kizuna Encounter characters, or was that not enough? Did you need more?

HS: We were working on fighting games, and that was fun. But inside I was yearning to make some kind of free-roaming game, where you could actually roam around. But the tech just didn't exist at the time. So when Super Mario 64 came out, I was in complete shock. It blew me away and made me think, "I need to make something like this."

What kind of roaming game did you have in mind back then?

HS: At the time, I was really in love with fighting games. There were great games that were coming out: Virtua Fighter, Tekken. I was thinking in my mind, it would be fun if I could make characters that moved around like Jackie Chan inside a town. You could go breaking down dojos and picking fights and walking around town.

So not talking, not interacting, but action-oriented.

HS: Yeah, that's right.

That would have been around the time you were working on The Last Blade at SNK.

HS: Yeah, it was probably around the time that The Last Blade came out. I was really shocked because their game came out at a similar price as my game.

You worked on The Last Blade 2, after that, right?

HS: Yes.

How did you come to move away from SNK?

HS: I hit a point where I wasn't sure what I wanted to make anymore. This may sound weird, but I went on basically six months of vacation time to look for what I really wanted to do. I went on trips, went on voyages, trying to look for what I was missing and trying to find, basically, myself. Then when the time came, I went to work on Tomba! 2 at Whoopee Camp.

That work came at the conclusion of your six-month sabbatical. Had you come to a conclusion? Did you come any closer to finding yourself, or were you still trying to figure that out?

HS: No, I definitely did not find who I was yet. I just ran out of cash and needed work.

What was your involvement in Tomba! 2?

HS: I was working on the level design for the latter half of the game, and also setting up the AI movement, how the enemies moved around.

What came after Tomba! 2?

HS: The next game I worked on would be Extermination. The studio developing that game, Deep Space, was on a separate floor from Whoopee Camp, so I just switched floors and switched jobs.

You were the lead designer on Extermination.

HS: Yes. On the list of planners, my name came first. [Ed. note: in Japan, designers are called "planners".]

That's a big jump, going from doing enemy AI on a 2D game, to being the lead designer of a large, 3D game.

HS: At the time, when I was working on the game, I thought I was just one of the planners. I was eager to learn a lot, so I kind of volunteered. Like, "Hey, can you give me some more work?" "Hey, what are you doing? Can I help with that?" That kind of thing. Subconsciously I learned a lot, and toward the end of the project I was the lead.

Ah. So Extermination is not necessarily your vision, this was a project that started before you.

HS: Yes, that's correct. The project already had begun when I joined, so there were things that were working and weren't working when I joined. I tried to fix what I could and make the changes that were needed as a planner.

Deadly Premonition had a character named Forrest Kaysen. Spy Fiction also had a character named Forrest Kaysen. Extermination had a company called Forrest Soft. Are you connecting all of your games together?

HS: Uh, yes! They are connected. It's hard for me to reveal this. I'd like to keep it a secret...

What, forever?

HS: At the current time I feel it would be best to keep it a secret.

Are there more references to Forrest that I didn't see in your previous games, or is it just the three?

HS: In regards to games that have already been released, it's just those three. But you never know about the future.

I'm surprised that you noticed Forrest Soft. You're the first person to ask about it.

Also, SWERY 65 is a bar in both Deadly Premonition and Spy Fiction. I don't know if there's reference in Extermination. I didn't finish it. Is that part of the same secret?

HS: Extermination also does have SWERY 65 in it in a similar fashion. But that would be a separate secret from the Kaysen secret.

Spy Fiction was your next game. That was Access Games, which, if I'm not mistaken, you co-founded.

HS: Yes. Access Games was founded by six people, including me.

Did you all come from Deep Space?

HS: No, we came from separate companies. Of course there were a few that came from the same company, but we weren't all from the same place.

Was Spy Fiction the first project that you started at Access?

HS: Yes, that's correct.

You've remarked before that Spy Fiction was a particularly challenging project for your team.

HS: We had a lot of work to do with a very tight deadline and not very many people. We were doing stuff that we didn't have that much experience with, like English voiceovers and motion capture. We had to do all of that stuff. And while doing that, there was also the pressure of putting out the team's debut title. So we wanted to make sure this would be really good. Trying to do all that at the same time was really difficult.

Spy Fiction

What is the philosophy behind Access Games? Why did the six of you found it, and what do you hope to accomplish as a company?

HS: Our thinking is to make action games that can be sold on the worldwide market -- trying to generate like games like that in Osaka, and have them sold all across the planet.

What is the team size now? You started with six, what did it grow to?

HS: We currently have 50 people in-house, and maybe 20 freelancers.

Your next project was Rainy Woods, a game that was eventually canceled, though much of its work was recycled for Deadly Premonition. What was the genesis of that game?

HS: In the beginning, we were thinking of having some kind of scientific crime mystery-solving story, kind of like X-Files meets a murder mystery. I wrote up a proposal for that, and then we met with our producer. Through discussions, we were all thinking well, maybe it would be more fun if we gave it an occult theme.

It started as a story and world idea, rather than a game design idea?

HS: I don't remember all the details of that time, but I do recall we were working on the game design stuff and the environment and universe at the same time.

This game went through a lot of iteration and changes. In the earliest days, what did the game seem like in your head? What were you imagining?

HS: At the time, we were thinking, "Well, this could become a PSP game, a small action-adventure game that you can take with you." That kind of evolved into turning this game into an Xbox 360 and PlayStation 2 [Ed. note: Not a typo!] multiplatform game. It turned into an action-adventure, and we weren't anticipating that it would snowball into such a big thing.

It started as a smaller, simpler action game, but grew as you worked on it?

HS: Yes. That's right. Through discussions, the project became bigger and bigger. And through the process, I saw this as an opportunity to make the game I wanted to make, and utilize the free-roaming elements I wanted to make, and some of the story elements I had ideas for, and the gameplay ideas I had too.

It incorporated ideas that you wanted to explore before, but weren't able to?

HS: Yeah.

What was the inspiration for setting the game in the American Northwest specifically?

HS: When I was a child, I had relatives that lived in Winnipeg, in Canada. So I've been to that place many times, just to visit my relatives. But at the time we were thinking, we want to make this game be a successful game in the United States, so it would probably be better to choose a place within the U.S. And I was thinking, "Well, why not have that place be somewhere close to Canada?" And that just happened to be Northwest U.S.

Specifically you studied North Bend, Washington.

HS: I've been there to check things out for the game, for reference, yes. In a similar fashion, I've been to places in Washington, other places in Oregon, and places in California.

Also, we did the voiceovers here in California, and we took that as an opportunity to take more reference photos and footage. And when we returned back with all the footage, we'd give all the feedback to the remainder of the team to make modifications.

I enjoyed the photo gallery of your reference trips in Deadly Premonition. It's good to see some behind-the-scenes aspects of game development included in the package.

HS: For people who have played the game to the very, very end, I thought it would be a good idea to allow for the gamer to be able to see more of the stuff behind the scenes, maybe even see some of the faces of the people who worked on the game. I understand it's not for everybody, but it's something that we put in there.

It's something games could use more of. Like, disc 2 of a DVD set, where the special features usually are. You have quite a few extras like that in Deadly Premonition. Were DVDs an inspiration?

HS: Yes. When we were developing Deadly Premonition, we thought of it like an episodic TV drama. When you think of those DVDs, they usually have some kind of extras inside them. We liked that idea.

The original game, Rainy Woods, was cancelled, and then Deadly Premonition was signed as a separate project.

HS: That's right. We had to close the project for Rainy Woods, and we needed to start anew for Deadly Premonition, though we had a lot of assets to work with.

The footage we have of Rainy Woods looks like practically the same game, at least as far as art and story. How similar was the actual game design?

HS: When we rebooted, basically, we had to start over with the new project. I had to go through the process of thinking about what kind of gameplay we preserve, and what should we change. A lot of it, we had to go through a selection process, basically. One thing I remember changing was the controls of the character. That's something that was changed.

Deadly Premonition strikes me as being a much larger and more complex game than we had seen both from Access Games and from your U.S. publisher, Ignition. Is that because you were able to use the work that was already done on another game? In a sense, is it fortunate that Rainy Woods was canceled?

HS: After Rainy Woods was canceled, there was some time before it got rebooted. And during that time, I'm pretty sure I matured a little bit more as a game designer. I learned a little bit more. So when the project got rebooted as Deadly Premonition, that experience, that knowledge, I'm pretty sure was helpful in making the game better.

Deadly Premonition

You mentioned earlier being energized by the interactions you've had with fans over Twitter. Is this the first time you've had a direct connection to your game players?

HS: In the time before Twitter we had questionnaires that shipped with the game. Whenever I received positive feedback from those, that was definitely an energizing experience. Also, when the games that I've worked on were actually released, I'd go to the store and sneak a look and see who's buying the game. That was another kind of energy-receiving experience.

But this time, the reaction from the people who are playing the game, the response from them, was a lot bigger than I was anticipating. The size of the energy, I guess, is much bigger than what I've experienced in the past. What you can do now is receive feedback not just in real-time, but from all around the world.

So this is probably your first time interacting with English-speaking players of your games.

HS: That's correct.

You seem very comfortable with yourself now to me, in person. You seem comfortable and confident. Have you gotten closer to finding yourself?

HS: Because of Deadly Premonition, I'm receiving daily tweets now. People seem to be enjoying the game. And that has really fueled some of my confidence and courage, which is probably what you're seeing. Did I find myself? Maybe. I'm not sure. There are probably other elements of me that I should still be looking for.

You once ended a Gamasutra interview with "I love you all." It also says that on your business card, here. Is this a recent feeling for you? Is this a result of this conversation that you've been having with your fans? Or have you always felt this way?

HS: This is not something totally recent, but I've started saying this after Deadly Premonition came out, because people would say to me that they loved the game. Or there are parts that they really adore, there's a lot of love in their comments. In order to kind of reciprocate, I wanted to use the word "love" too, and it turned into "I love you all." And that's a phrase now that I use often.

Thank you very much, SWERY.

HS: [In English] Thank you. I love you all!

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like