Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

'One of the hardest priorities to fight for as a designer is player motivation. Keeping the player fantasy not just in your mind but in everyone else’s can be a constant challenge, especially if a different fantasy is seen as potentially more profitable.'

It sounds like an obvious idea for a game, right? What if you and your friends could team up online as a collection of superheroes, to fight crime and save the world from… whatever it needed saving from. The details aren’t that critical, except insofar as that is historically where the proverbial devil is.

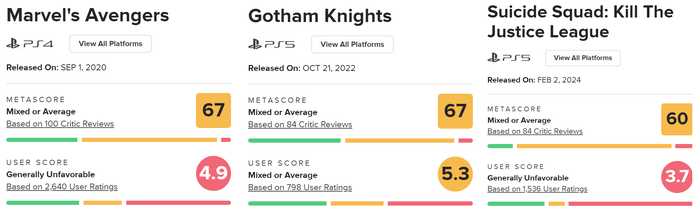

But we’ve now seen 3 high-profile attempts at this - Marvel’s Avengers by Crystal Dynamics, Gotham Knights by WB Montreal and Suicide Squad by Rocksteady - and the results have been underwhelming thus far. Surprisingly so, given the track records of those teams.

There’s a few issues to dig into here, though they all revolve around the same concept.

Critics have not been kind to these games, and users even less so

Games are often marketed and sold on the basis of providing a fantasy for the player. Not in the “wizards and rogues and ancient evils” sense, but the more general “getting to be someone else and live an exciting life that would otherwise be unavailable to most of us” sense. The nature of these fantasies varies greatly from one game to the next, but superheroes present a highly desirable player fantasy, which is why our medium has a long history of both adaptations and original superhero narratives. Given their prominence in the popular culture in recent times, there’s obviously a market for videogame takes on famous heroes, and to my mind, few have succeeded better than 2009’s Arkham Asylum and it’s 2011 follow-up Arkham City.

The combination of gameplay elements present in these games weren’t just fun - they absolutely nailed what we imagine it would be like to be The Batman. Taking down enemies from the shadows, winning fist-fights with a dozen goons, gliding through the air, using a variety of gadgets, outsmarting The Riddler, and the list goes on. Not only were all of these generally well-executed in isolation, they line up perfectly with the players existing expectations of Batman’s skillset, and this harmony will likely help the player enjoy the game even more than if they hadn’t come in with any expectations at all. No game can do everything, nor should they try to, but a game that allows the player to do all the things that they expect to do is more likely to make a good impression.

Two things most game designers are probably well acquainted with by now are that you will never have the time to plan out your entire game before you have to start building it, and nothing ever goes entirely according to plan anyway. As such, a large portion of game design is problem solving - you have a goal, a series of tools, a bunch of constraints, etc,. and you figure something out.

What constitutes the best solution depends on a variety of factors - scope, risk, licensing issues, etc. But one of the hardest priorities to fight for as a designer is player motivations. Many designers probably face repeated questions of “Why don’t we just do [insert feature from other game the questioner likes]?”, and keeping the player fantasy not just in your mind but in everyone else’s can be a constant challenge, especially if a different fantasy is seen as potentially more profitable.

Most of the criticism leading up to the release of Suicide Squad focussed on the live-service nature of these games, and not without good reason. These games, taking after the likes of Destiny and The Division and their earlier MMO inspirations, often place a large focus on a continuous, slow power grind. While such systems have proven successful in other contexts, you’re probably not the first to notice that they’re not an obvious fit for the superhero power fantasy. I for one have never seen a superhero story where the hero overcame great adversity by beating up enough goons to gain the XP required to earn a 5% damage boost.

That is not to say that superheroes are not concerned with getting more powerful - it’s pretty common for them to be very worried about whether they’re capable of facing the next challenge - but it rarely comes about in tiny increments via routine small-scale acts of heroism. Instead it tends to happen in meaningful bursts for plot-related reasons. This is part of what makes the classic metroidvania (or ‘unlocking world’) structure perfect for a game like Arkham Asylum - the hero gets more powerful/capable through the acquisition of new abilities at the specific moments of the designers choosing.

It’s easy to mock the idea of superheroes being reduced to grinding for loot, because it feels so inherently unheroic. But this just begs the obvious question of why they’re in this position to begin with - i.e. the nature of a live-service game is to have the players do something repeatedly, but why this? Though in writing that, we can see a second issue - the very nature of superheroes is that the’re exceptional, and exceptional individuals can only be challenged by exceptional problems. So again we find that the very nature of the superhero is being undermined by the idea of a game where the player has to do some tasks routinely. Though given that the nature of almost every game is to do variations on a task repeatedly, this one is a little more understandable. And if the tasks being repeated are great, highly enjoyable ones, then we can assume many players would be willing to overlook this paradox. So we return to the question of “Why this?”

Still an exceptional game, in multiple senses

Earlier in my career I was approached about a level design opportunity for a [non-superhero] co-op game. Trying to appeal to my love of puzzle games, I was told that each selectable character would have unique abilities and that part of my role would be to create situations where the characters would have to use those abilities together in novel ways to overcome environmental obstacles. This intrigued me at first, but only until the other shoe dropped - the brief also called for both drop-in/drop-out multi-player and that all players could be the character of their choosing. In other words, while you could imagine a group of distinct characters working together, we also had to accommodate a single player with any character or up to four of the same character, and for the composition of this team to change mid-level. Perhaps it represents a lack of imagination on my part, but at this point my excitement turned into a fear that I was being asked to do something inherently contradictory, and rather than creating complex and interesting challenges that relied on the unique abilities of each character we would end up only delivering simplistic ones that could be completed by any collection of 1-4 characters. We never found out, as the project was abandoned shortly after.

Why the flashback? When I look at these superhero co-op games, I suspect that they come up against very similar problems. Different superheroes can have wildly different abilities, but if the designer can’t rely on any specific one being present, then they can’t design any scenarios specifically around them. Perhaps you can have the AI control them, but that’s both asking a lot of companion AI and potentially having AI do a lot of the interesting things that players would rather be doing. So they’re faced instead with the fallback question - what do we know for sure that any superhero or group of heroes could do? And the most common answer - maybe the only answer - is that they can beat up groups of enemies, or sometimes a single strong enemy, and… that’s about it.

Compare this to the variety of actions from Arkham Asylum described earlier and you see the problem - the addition of new heroes, rather than expanding the scope of the gameplay, can actually contract it. Each one may control differently and have different options available to them, but these differences are often relatively minor in context and put in service of the same outcome - dealing damage to the enemies until they’re all down, rinse and repeat. And so the fantasy of being a specific superhero, with all their unique abilities, gets whittled down to a few different options for beating up waves of generic foes. All of the more diverse array of abilities that the heroes may have - the things that they and only they could do - can get scrapped because they don’t fit the brief or justify the effort. Such is the level of character flattening in Suicide Squad that a woman most famous for wielding hammers and bats and a man literally named “Captain Boomerang” both spend most of their time using firearms instead. Both are also given traversal mechanics completely unrelated to the source material to put them more in line with the rest of the squad. This flattening is made even clearer when there are notable power differences between the heroes present, as is often the case in superhero team-ups. In a co-op game primarily about attacking enemies, Black Widow needs to be as powerful as Hulk, Batman as powerful as Superman. And so the fantasy is further diminished. Notably, this issue would still remain even without the live-service element. It is the consequence of trying to shoe-horn this fantasy into a style of game that just doesn’t seem to support it.

None of this means that you can’t ship a great game with these constraints. Critics of all of these games often acknowledge that there are many good qualities to be found in them. But when you make games based on established characters, you’re not just selling it on brand recognition, you’re selling it on the fantasy of being the character. This means that the inherent qualities of the game can get lost in players expectations. As the developer, knowing why you came up with these compromises and having had a long time to acclimatise yourself with them, you may be convinced that you’re shipping a great game. And in a different context you might be.

So we started with a vision of a heroic team of special individuals, combining their unique skills to overcome challenges that no one else could handle, but what we got were games where a team of mostly interchangeable characters beat up generic goons to slowly accumulate power to get marginally better at beating up more generic goons. The original fantasy is largely lost, at least in part because that fantasy was likely always unachievable. Look at how hard it is to deliver on a compelling superhero fantasy for a single hero. You can name the games that have done it successfully in the last couple of decades because they’re so exceptional. So how much more work is it to make a collection of compelling superheroes in a single game, and how much more work on top to figure out how to have them all be working together in a way that each role is both fun and necessary? If we’re being honest, even the films sometimes struggle with this - as Hawkeye notes in a semi-fourth-wall moment in Age of Ultron: “The city is flying, we’re fighting an army of robots… and I have a bow and arrow. None of this makes sense.” And in film it doesn’t necessarily have to - the screenwriter of an action scene just needs a few moments of each character making interesting use of their skillset, cut together in rapid succesion, and the audience leaves thinking that every character was doing their part.

But a game designer can’t pull this trick - they want all the characters to be fun and useful all the time. So all of the decisions that lead us here are understandable, if not inevitable. In design it’s always hard to say for sure if problems are unsolvable, so it’s always possible someone figures out a way around all of these issues, but several highly skilled teams have already taken a crack at this. I don’t want to end on such a downer though, so let’s look at a few ways that we can tweak this idea that could work around these problems.

Not all hero-based games share these problems

One of the simplest tweaks is just to switch from the player controlling one member of the team to controlling all of them - e.g. removing co-op. For an example of this, we can look to 2021’s Guardians of the Galaxy - here the player primarily controls Star-Lord, and directs the rest of the team, and it doesn’t suffer from most of the issues laid out above. It doesn’t matter, for example, if only one member of the Guardians can do anything useful in a particular scenario if you’re effectively controlling all of them. Nor do long stretches of non-combat sequences prove a problem, enabling a greater breadth of gameplay.

Similarly, 2022’s Midnight Suns puts the player in charge of multiple heroes at once, which allows for them to have meaningfully different roles within the team, even if in practice these usually slot into a few classic role types. In this style of game, not only is it ok to have characters that aren’t as effective in direct damage dealing, the player knows it is their job to make this team work well together, utilizing the strengths of each.

Another alternative is to simply change the type of game you’re making to one where the audience is less likely to consider these constraints an issue. For example, the problems mentioned above about each superhero being interchangeable and only engaging in a series of fights wouldn’t seem like a problem at all if you’re making a tag-team fighting game - the Marvel vs Capcom series for example. You even get team selection, multi-player and the possibility of a post-launch content roadmap, but that’s in exchange for giving up a core part of the premise discussed above - you’re no longer trying to embody the fantasy of being Tony Stark, you’re just playing as him in the context of a fighting tournament.

Other similar pivots might include gameplay models more like OverWatch* or League of Legends, which similarly allow for team-based play with specialized heroes serving different roles, though like the fighting game comparison, the larger context of the superhero narrative is sacrificed and the long-term retention play here is through competition and mastery, which is likely appealing to a different audience of both creators and consumers.

*I wrote this days before the announcement of Marvel Rivals , which was a happy coincidence.

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like