Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

In bringing Sublevel Zero Redux (our roguelike six-degree-of-freedom shooter) to VR we've had to overcome serious design and technical challenges. We dive into some of the solutions we've implemented to make such an intense game a great VR experience.

Our debut game Sublevel Zero is a procedural six-degree-of-freedom shooter heavily inspired by classics like Descent and Forsaken, with modern roguelike influences such as Teleglitch and Rogue Legacy. We initially released it all the way back in late 2015, but we've kept tinkering with it since and we're launching the VR version, Sublevel Zero Redux, for Vive and Rift on the 13th of July.

As a two-man studio it's taken us a long time to get to this point! We thought it would be interesting to go through some of the challenges, both technical and design, that we've had to deal with in making an intense zero-g shooter with procedural elements into a great VR experience.

In finalising the VR version of Sublevel Zero Redux, we’ve done extensive research and development into comfort. Sublevel Zero is a perfect case study for sim-sickness - a game where players move and rotate freely in all directions, often with no well-defined up or down orientation, at high speed, while dealing with intense combat and enemies coming from all angles. Our work has led to a number of really useful conclusions, and we’ve presented our work at conferences such as Unite Europe and Develop:VR.

As a result, the VR and non-VR versions of Sublevel Zero Redux have diverged not just in aspects like UI design, but even in physics. The ship’s handling is actually significantly “twitchier” in VR, while maximum turn rate is decreased. This decreases the amount of time spent accelerating rotationally, and thus decreases the amount of force the brain expects to feel. Furthermore, we found these tweaks were needed to make the game feel the same - in VR turning felt uncontrollably fast despite being identical. Added to this is the “tunnelling” effect seen in the game. When the ship turns, this reduces peripheral vision, from which the brain gets a large amount of its sense of motion. We’ve found for many players this makes the difference between a comfortable game and an instant vomit-fest.

Taking inspiration from the work others have done in this area, we’ve expanded the tunnelling options even further. Google Earth VR introduced a novel twist, by not just blacking out peripheral vision, but replacing it with a “grid”. This can work wonders to give players a solid frame of reference, making the motion “on screen” seem disconnected from reality. Adding this mode has given us some really positive results.

We’ve also added a mode to exclude the cockpit from the tunnelling effect. Since the cockpit is already a fixed frame of reference, it makes sense to keep it visible. Finally, up til now the tunnelling effect has been driven only by turning the ship. Players can now select two other modes - turning plus acceleration, and turning plus movement. In the former, tunnelling also kicks in when the ship is accelerating, and in the latter, is always present whenever the ship moves at all. These modes can really help motion-sensitive players enjoy the game.

Added to the existing tunnelling strength setting, this ends up in a lot of options for players to fine-tune comfort settings. We feel strongly that this is important - a key takeaway from our research has been that everyone responds differently, so player control is essential. But when does “lots of options” cross the line into “overwhelming mess”? Options are great, but not if the player doesn’t know what they do! With all these settings, the number of possibe combinations - not including off - is 24. Ok, so maybe not hundreds, but considering it takes a little while to see if a change has improved things or made them worse, fully exploring them all sounds a lot like hard work.

So we've implemented presets, which change all the settings at once to some useful defaults we've found by experimenting. Obviously this is a big improvement. Now instead of fumbling around with 24 combinations of settings - the effects of which are individually somewhat complex, let alone when combined - you can try out the broad strokes and get a feel for what does what before diving into the details. But we still didn't think it was quite good enough. Sim-sickness (sorry to keep banging on about this point) is a highly subjective problem. To go into a menu, change a preset, then go back to the game, still gets in the way of directly and easily comparing settings. Players need to be able to feel the difference seamlessly.

So we came up with a novel approach. Instead of making you go to the menu, fiddle with settings, return to the game and repeat (while avoiding getting shot, no less), what if there was a dedicated mode in the game just to experiment with? A mode where you can fly around without worrying about enemies or anything else, seamlessly change comfort settings and quickly get a feel for them?

Thus the Comfort Calibrator was born. Accessed from the main menu, one can dive straight in and try things out. Instead of firing weapons, the fire buttons (whether you're using mouse, controller or joystick) switch between presets. This means players can switch presets while in the middle of a turn or a loop-the-loop! What better way to find out what works for you?

Note that this is presets - there are too many individual settings to usefully map to input methods, and it'd get confusing fast. So once you've hit on a preset you like, you may still have to dial in specific settings from the menu. But the key difference is players will already have a good understanding of what works for them and what doesn't.

Getting the game to run smoothly in VR has been a tricky task. While the look of the game is colourful and stylised, early decisions on the underlying technology to deliver that look have come to define the performance aspects of the game under the extreme requirements of VR.

Primarily among these is the procedural generation. Early on - well before the true performance requirements of VR were established - we decided to use deferred lighting for Sublevel Zero. This meant we could use fully-dynamic lighting, with hundreds of lights, rather than having to bake lighting into the rooms used in the procedural generation. Unity’s system of light baking was at the time impossible to use with procedural generation, as it linked baking to levels, not individual objects. So we either had to create our own baking system - infeasible with our team and budget - or use deferred lighting.

This decision served us incredibly well for the most part. It allowed us to create and control a unique, vibrant, neon-saturated look that perfectly complemented the feel of the game, and on regular systems, run totally smoothly. But it later became clear that deferred lighting was VR’s nemesis. It saves CPU time, but pushes the GPU hard. And in VR, the number of pixels to render, and the number of times per second they must be rendered, is enormous. Valve estimate that the average VR game rendering to the Rift or Vive at 90fps is roughly equivalent to running a game in 4K at 50fps, pushing about 500 million pixels per second. In Sublevel Zero - lots of deferred lights writing each pixel multiple times - fillrate goes through the roof. Suddenly, our simple, stylised game becomes a bona-fide GPU melter.

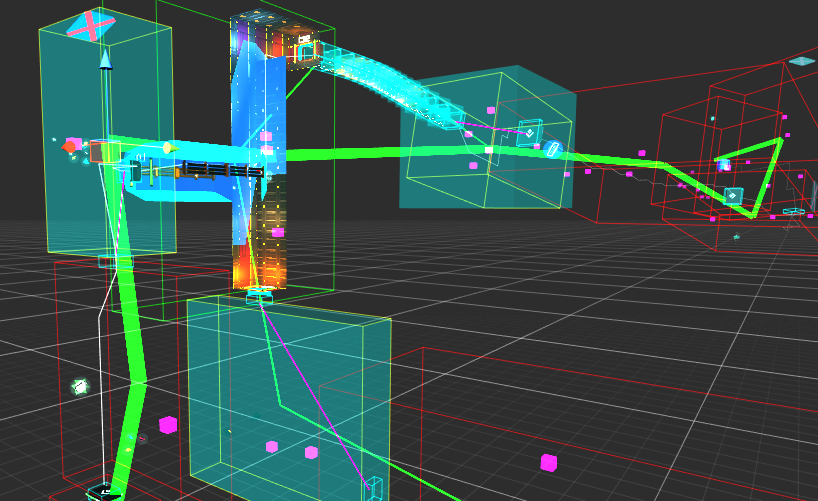

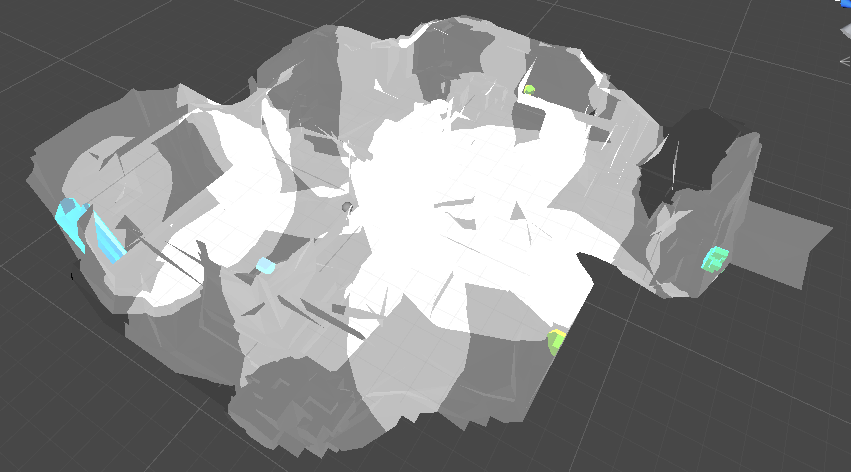

Culling visualisation. Turquoise boxes show rooms which can be seen from the current room, but the player isn't looking that way. Red boxes are rooms that can't ever be seen from the current room.

We’ve managed to get this down with lots of small tweaks and tricks, like using the procedural generation data itself to work out which rooms the player can't currently see, and turning them off. We've also developed a tools pipeline that helps us optimise lighting, minimising the number and radius of the lights used to significantly reduce overdraw. This has in many cases allowed us to halve GPU time spent on the deferred lighting pass, particularly in areas like the reactor boss fights.

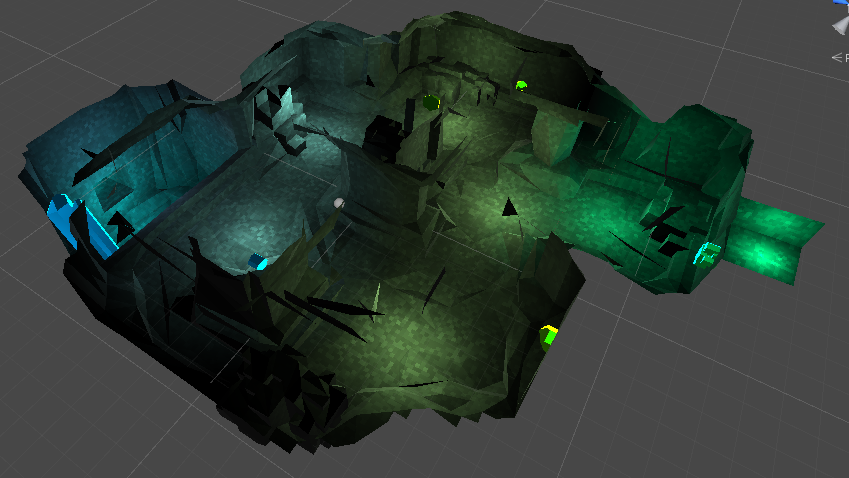

A typical room prefab for procedural generation.

Viewed with the lighting overdraw visualiser. White is four or more writes to the same pixel.

Optimised to reduce deferred lighting overdraw.

To do this we've rewritten Unity's deferred light pass fragment shader to simply output a constant additive value. This behaviour is toggled using a shader define, linked to a hotkey. We're then able to iterate upon lighting extremely quickly, easily seeing both the visual and performance characteristics.

Various effects switch to a subtly lower quality setting in VR, and we have two separate config files for all graphics settings (and also settings like screen shake) - one for VR, one for non-VR. So tweaking quality settings in non-VR mode won’t mess up the performance of the game in VR, and vice versa. Finally, if the GPU is still struggling, headset resolution can be decreased (or increased, for your Titan One Million) with a setting that changes the VR render target parameters.

It's been a long road to getting Sublevel Zero Redux finished. We always knew it would be great in VR, but we had to learn the hard way that designing for both VR and non-VR simultaneously is extremely tricky. Since we started out at the beginning of this generation of VR, lots of technical knowledge now taken for granted had to be found through trial and error. Using deferred lighting was a great choice for Sublevel Zero in the first instance, but has caused significant technical challenges for us down the road.

Likewise, comfort in VR for such an intense game is no easy thing. We’re hopeful that our efforts will help players of all stripes get the most out of Sublevel Zero Redux in VR. Make no mistake - Sublevel Zero Redux will never hit Oculus' minimum "Comfortable" rating! We won’t compromise the fundamental core of the game - free, fluid movement and hardcore zero-g combat. It's probably not the VR game to show the grandparents. But we're confident that most players will be able to enjoy the game, and we think Sublevel Zero Redux stands as a great case study of taming an exceptionally intense experience.

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like