Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

Battling the Nazis in World War 2 is a frequently-used setting in video games. Yet, in Germany, the homeland of the Nazis, video games were not allowed to show any of their symbols. This has changed now. Here is how, why and what this means.

Germany: famous for its Volkswagens, its beer, its lederhosen - and a young Austrian named Adolf Hitler, leader of the Nazi-Party NSDAP, who became chancellor in 1933. Back then, many Germans happily followed Hitler through 12 years of murderous dictatorship.

During that period, Nazi Germany committed a genocide referred to as the Shoa. The government and its helpers systematically killed six million European Jews, and millions of members of other groups such as ethnic Poles, Slavs, Roma, the so-called “incurable sick”, and Soviet citizens.

In 1939 Germany attacked Poland, firing the opening shots of World War 2.

Battling the Nazis in World War 2 has been one of - if not the most - frequently used settings in video games, for almost as long as such games have existed.

The original Castle Wolfenstein came out in 1981, tasking the player with infiltrating a Nazi stronghold and securing vital intelligence. Nazis have been one of the go-to enemies for games developers ever since.

Players all over the world are used to seeing Nazi symbols like the swastika or the black uniforms and Armanen runes of the SS in their games.

Except in Germany.

After the Allies defeated the Nazis, the founders of post-war Germany decided to ban the Nazi party and all its symbolism.

This gave birth to §86a of the German Criminal Code, which

outlaws the "use of symbols of unconstitutional organizations". The first organization considered “unconstitutional” was the NSDAP - the official acronym of the Nazi party. But contrary to popular belief, it is not the only one. The KPD (“German Communist Party”) was banned in 1956, and to this day dozens of organizations, from both left and right, remain on the list.

The reasoning is that in order for the state to defend the freedom of its people, it needs to deliberately limit freedom of speech when it comes to these symbols as a counter to the threat from the organizations they represent. It is also a concession to the victims, who should not have to confront the symbols of their tormentors ever again.

Anyone who violates paragraph §86a by showing such a symbol, sign or “typical gesture” - like the Nazi salute - is punished with a fine or up to 3 years in prison.

But what about movies or documentaries? What about museums, memorial sites or exhibitions? Shouldn’t they be able to freely show these symbols, to remind people how things were?

How should the next generations of Germans even learn what symbols to avoid, if they would never see them? How should they learn about history?

There are exceptions. It is legal to show symbols, signs and gestures of unconstitutional organizations if inside “the context of art or science, research or teaching”.

Therefore, in history books,movies ,theatre and museums it is perfectly legal to show swastikas.

With games it has been a little more complicated. While games in Germany have recently been officially declared a “cultural asset” (which is as close to a nomination for being an art-form as any medium could ever hope for), you still cannot find Nazi symbols in any games released in Germany.

Why was the exception that was applied to movies not applied to games as well?

Are games a lesser art-form?

If you want to sell or advertise your game in Germany, it needs an age rating from the USK. Founded in 1994 by the German games industry, the USK is a private organization which cooperates with German youth-protection authorities, and rates games in a legally binding way.

It provides legal certainty for publishers and developers, as once your game has received an USK age rating, it cannot be banned. At the same time, retailers are obliged to comply with the restrictions indicated by a game’s rating.

This is a major improvement over the times before the USK existed, when German youth-protection authorities frequently - and inconsistently - banned games they considered to be harmful to minors.

But here’s the problem: to get your games rated by the USK, you - the publisher or developer - have to legally certify that your game does not contain any symbols of unconstitutional organizations.

This is where the trouble arises. Games containing swastikas are no more or less illegal than movies containing swastikas - but developers needed to remove them for their game to be officially rated by the USK.

But why did the USK even ask for this assurance in the first place?

While the USK is a private organization, it works closely together with the youth-protection authorities. The ratings rules are developed by both organisations together, and the authorities have final say over ratings and approvals.

In 1998 a group of German Neo-Nazis distributed pirated copies of the game Wolfenstein 3D, which contained swastikas and images of Hitler, through a network of mailboxes. They were caught, and indicted for violation of §86a. The judge found them to be guilty; his argument was that, even though as a player you fought against Nazis in Wolfenstein 3D, the game’s “interactive manner” meant it could be used to “glamorize” Nazism.

This may sound odd, but keep in mind that he was looking directly at the faces of a group of actual, self-professed Neo-Nazis when passing this sentence.

While this verdict was not in principle binding for any similar future cases, the highest German youth-protection authority found that this was a clear indicator that games should never contain symbols of unconstitutional organizations. They made the requirement that a game must be free of those in order to gain a rating through the USK.

This ruling led to several bizarre events over the next 20 years. For example, Bethesda created an entirely new universe for its Wolfenstein series’ German releases, in which the Not-Nazis looked very similar to Nazis but just different enough to obey the rules. Hitler became Heiler and lost his toothbrush mustache.Jews - the principle victims of Nazi atrocities in the real world - were replaced with generic “traitors”, airbrushing them out of history.

Ubisoft had to call back one edition of the South Park role-playing game Stick of Truth, because it had accidentally printed and distributed DVDs where they had overlooked a single swastika.

The Czech indie game Attentat 1942, a historical game about civilians suffering from Nazi repression after the attack on Auschwitz architect Heydrich, won the “Best Game Award” at the indie-game festival A MAZE. in Berlin. The judges could only play it behind closed doors, because it could not be rated by the USK due to its “no unconstitutional symbols” requirement. This same reasoning prevented it from being sold on the Steam online store in Germany.

To emphasise this: A historical game about an attack on one of the worst German Nazi criminals, made in the country of their historical victims, could not be shown nor distributed in the country of the historical perpetrators due to a law made to protect the people from Nazism.

This makes no sense.

Luckily, there were many people who saw it this way, and some of them have talked to us about it.

My partner Sebastian St. Schulz and I are running the 2-person indie studio “Paintbucket Games” in Berlin, and are working on a game called Through the Darkest of Times. We have been working in games for 15 years, and we met when we both worked at YAGER on Spec Ops: The Line.

Through the Darkest of Times is our studio’s first full game.

In TtDoT you play a civilian resistance fighter in Berlin during the so-called “Third Reich”. You form a group of like-minded citizens and fight the regime by winning supporters, helping the persecuted, and trying to sabotage and attack the Nazis however you can. The challenge is to keep your members together and balance their diverse needs, problems and motivations, while avoiding being arrested (or worse) by the Gestapo.

We believe that the world today is in a state where it needs more games about people who overcome their differences to fight an inhumane regime.

When we started developing TtDoT, we looked at many other games and found that most didn’t treat the topic very well. While in many games Nazis are shown as enemies who are somewhat evil, they are often just another faction of bad guys. The faction that no-one else likes, but has the best tanks and coolest uniforms.

Frequently they are portrayed as “stupid evil”, echoing the Empire in Star Wars. True atrocities, and the Shoa, are usually left out. We wanted to change that.

We also didn’t like the fact that many games just copied the aesthetics of the Nazis, without paying any attention to their actions.

As a game about resistance, we wanted to do something different, and were inspired by artists who the Nazis had banned, like Käthe Kollwitz, Otto Dix and John Heartfield.

Our goal was to create an art-style that the Nazis would have banned as well.

We needed to find a way to deal with the §86a: We refused to create a fantasy universe and not call the Nazis by their true name, or make up our own symbols. Since we couldn’t use the real ones, and refused to create fake ones, the only chance we had was to deliberately leave things out. The result looked like the screenshot you saw at the top..

We found the result acceptable. It got the message across. Everyone knows who it’s referring to, and it stays within the law. Easy, we thought.

But the more we learned about the topic, the more we realized that it wasn’t so easy. Leaving out swastikas is one thing, but removing the Nazi-salute is much harder.

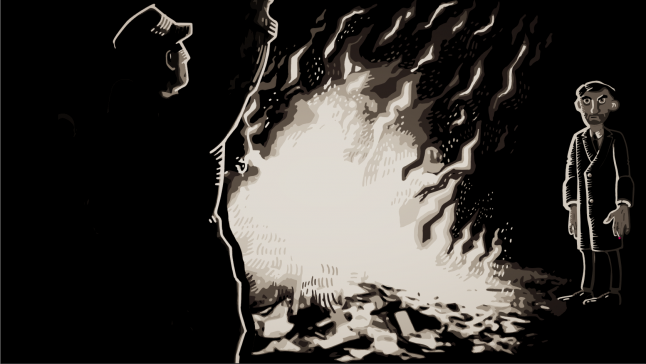

Sebastian created an iconic scene on the public burning of books in May 1933 based on historical footage. The Nazi students who directed the burning are seen standing around the fire, and performing the Nazi salute. All the while, Erich Kästner (a famous German writer whose books were burned) stands in the shadows and watches what they do to his work.

We realized that with the current rules, we would not be given an age rating by the USK, and therefore we could not show this scene in a game released in Germany.

This was when we realized that meeting our goals would be more painful than we had imagined. We started to play around with the scene, tried zooming in further so that you would only see the fire. The Nazi students would be cropped, hiding their saluting arms, but then Kästner was missing. The whole scene was rendered weak and pointless.

What had been clear, self-explanatory and iconic became vague and required explicit explanation.

We lost hours debating and pouring creative energy into possible solutions and workarounds. For a small team like us at Paintbucket, burning valuable hours like this is a huge issue. It means losing time that could be used to improve the game. We didn’t worry too much at the start, but over time the whole matter slowly started to get under our skin.

No other medium has this problem. No filmmaker would need to worry about this issue. They could just show what needed to be shown, because it is portrayed in the correct, legal context.

Because we were working on a game, context didn’t matter. No one would even evaluate it. No assurance, no USK-rating. No USK-rating, no sale in Germany.

It was unfair, and it began to make us angry.

We started to meet with people. After the weird “Hitler becomes Heiler” in Wolfenstein 2 episode, and the award-behind-closed-doors incident with Attentat 1942, there was a lot of debate within the German games industry, and also with politicians and authorities.

Many people shared our anger about this topic. Something was obviously wrong. Most Germans are perfectly fine with the limitation of freedom of speech when it comes to Nazi symbolism in public, but the way games were treated was broken.

We posted our censored screenshots on Twitter and found support from all sides. We came into contact with a lot of like minded individuals that we had never met before, who liked what we did and wanted to help us.

There were game industry veterans who gave us advice, and lawyers who offered us their services free of charge to challenge this rule in court. Journalists wrote about us on major German news sites next to games like Call of Duty, even though we were just two independent developers with a few images to share.

We met with a lot of people and discussed and dismissed different options. We considered going to court for the right to have our game evaluated for the context of symbols as well as their use - just like they would do for books or movies.

There were moments when we had serious doubts: was this really the right thing to fight for?

Under every article about our game we had comments of German players who demanded swastikas in their games. But there were also always comments of people who said they wanted that because Hitler hadn’t been that bad after all.

Were these the people we would make happy if we managed to get that ban lifted?

Was that what we wanted?

In the end we didn’t have to go to court. In a surprising move on the 9th of August, the “Oberste Landesjugendbehörde” (the highest youth-protection authority) changed the rules. After 20 years, they removed the sentence from the USK application that required developers to certify that there were no symbols of unconstitutional organizations in their games.

We don’t know how much influence we had on it, or if it was just coincidence, but we used the opportunity two weeks before Gamescom and applied with a version of our public demo. The gameplay contained swastikas and the uncut version of the aforementioned book burning scene, in which people show the Nazi-salute.

The demo got approved for children aged 12 and above.

Just like that.

As if it was nothing special.

20 years of special treatment of games are over.

This is a major change to games in Germany, but it does not mean that all regulation is over.

If you try to get a rating for a Nazi-propaganda game, you’ll be out of luck. And even for multiplayer or strategy games where the context isn’t as clear as in our case, the USK may decide differently.

§86a is still valid and active and the USK will check the context in which these symbols are used very thoroughly.

But the change still means that we are at the cusp of a new age for games in Germany.

In the third-largest global market for games, they are finally treated equally to any other medium, and it is accepted that games can be art.

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like