Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

How the door affects the human mind, and how games have used that transition in the past.

June 10, 2013

Author: by Dale Dobson

As the game industry matures, and gamers age with it, more of us are likely to have had this peculiar experience: we need to do something in another room; we go there; and by the time we arrive, we've completely forgotten what we intended to do.

It turns out that the human brain has a bit of an I/O bug when it comes to how memories are formed, a phenomenon explored by a number of recent scientific studies. A paper called Event Segmentation Theory (Zacks, Speer, Swallow, Braver, & Reynolds, 2007; summarized here) models our memory system in terms of "working memory" and "event boundaries."

Dr. Jeffrey M. Zacks and his team theorize that human short-term memory storage compresses experience to save space and energy, filling in the gaps with predictions and assumptions based on our expectations. For instance, if we put one shoe on, or watch a video of someone else doing so, we tend to assume that the other shoe was also put on after we subsequently "cut" to a memory of leaving the room.

Psychologists have recognized for some time that humans automatically fill in visual gaps -- we don't truly remember everything we "see," because the brain feels free to record the broad outlines of an image, making reasonable assumptions and even inventing details as those memories are processed, rehashed and stored. Zacks' theory expands this understanding to the realm of time, suggesting that we also organize our memories based on "event boundaries" -- we conclude that this event we remember happened, so therefore some other predictable events must have happened before the next event we actually remember occurred.

Most of the time this mnemonic shortcut works reliably -- though magicians and con artists are skilled at exploiting it -- and we're able to keep a mental record of recent events that's acceptably accurate. But the human brain seems to suffer an occasional bug when it comes to processing doorways, portals, gateways, and other physical borders -- these are major event boundaries as far as our working memory is concerned, and when we pass through them, the brain tends to clear our working memory out altogether. The "it isn't just you" school of scientific study lends some comfort here -- the study Walking through doorways causes forgetting: Further explorations (Radvansky, Krawietz, Tamplin, 2011; pdf here) confirm that this phenomenon exists.

Speculation runs rampant as to the underlying cause -- in evolutionary terms, it could be that human beings living a nomadic, tribally oriented lifestyle rarely encountered major physical boundaries. Good evidence suggests that we are an exploration-prone species, spreading across the planet in a relatively short span of time. And as we crossed from familiar territory into new lands with new dangers and opportunities, it may have been useful to abandon assumptions, reset awareness, and make ourselves ready for anything to happen. Our world has changed faster than we have -- our aging hardware still works great when we're leaving the Serengeti or crossing the Bering Land Bridge, but it's a bit of a handicap in the modern world, when our systems decide to shift context as we walk from the living room into the kitchen.

Earlier work by Dr. Radvansky in 2006 studied and confirmed this as a real-world phenomenon; the 2011 study confirms that it also occurs in a virtual environment. This suggests that the "doorway reset" is indeed a fundamental brain issue common to human beings, and one that applies equally to artificial worlds.

What does all this mean for the art of game design? One important takeaway is that human beings are not very hard to fool; at some fundamental level, our brains readily accept a virtual world as it if were real, even though it is devoid of reality cues like air movement and odors, and the lighting may not behave the way it does in the real world. The basic mapping circuits that enable us to learn our way around a neighborhood kick in just as they do in real life. And doorways play a part in our understanding and modeling of these artificial environments, and the events we experience there, just as they do in the real world.

Long before these studies were published, of course, game designers recognized the significance of doors in human experience. There's a natural inclination to use them as boundaries, and they are often technically convenient. In this article, we're going to take a look at some specific examples, and see how this new understanding of doorways may apply to their use and abuse in the art of video games.

The original adventure game, Crowther and Woods' Colossal Cave, featured no doors to speak of, having been modeled after the natural rock formations in Kentucky's Mammoth Cave. But the mainframe Dungeon's more familiar descendant Zork I features a couple of doors of note.

The Doors

The first Zorkian door, in a sign of things to come, is a total red herring -- the little white house that memorably serves as the player's entry to the Great Underground Empire has a front door, but it's boarded up and can't actually be opened. Later, inside the house, under the living room rug, we discover a second door, a trap door in the floor.

The Experience

The first door distracts us from realizing that we have to go around to the side, force open the kitchen window, and sneak in that way. And when we open the second door, and descend into the darkness, the game is seriously afoot, as...

The trap door crashes shut, and you hear someone barring it.

This Is Your Brain On...

The front door of the little white house provides a tempting gateway, but the designers pull the rug out from under our expectations right away. This door, this frustrating door that can never be opened, isn't really a dead end. What it's doing under our primitive hoods is setting up the desire to get inside the house -- after all, if there's a door blocking our way, there must be something desirable behind it. And after trying various magical incantations, random inventory item applications, and physical violence, we sooner or later begin to suspect that there might be another way into the house. Solving that simple puzzle by going in through the kitchen window instead is the player's first real accomplishment in the game, and when we see the other side of the door from the living room, we can put a mental pin in this task -- front door, breached; little white house, explored; check!

Zork's second door is more scary than satisfying -- in a scant 60 characters of vintage ASCII text, the world aboveground is left behind and we are trapped in the darkness below. This is the classical example -- the trap door unexpectedly closes behind us, courtesy of an invisible (though not inaudible) agency, and it marks a clear point of departure. We can't go back, and we don't know what lies ahead; our brains automatically reset, ready for anything, and our pulse rate picks up a little. If we have the magical sword in hand, it begins to glow as danger approaches; if we neglected to bring it along, our adventure is likely to be rather short. Nothing we have done up to this point matters much, really -- at least, that's how our brains react.

The coin-op video game industry was developing rapidly when Exidy's 1981 title Venture took a major step forward, implementing meaningful, perspective-changing doorways for perhaps the first time in visual video game form.

The Doors

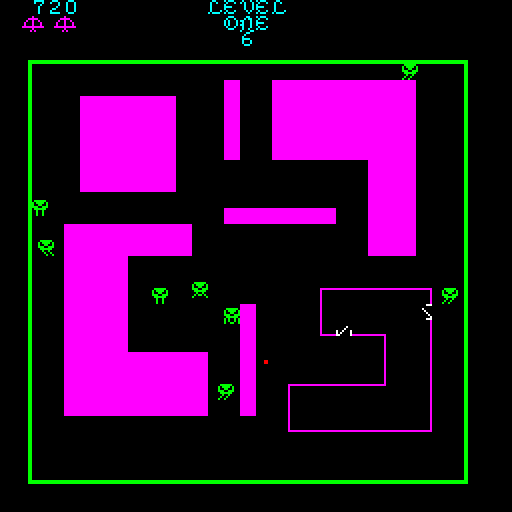

As the game begins, our bow-wielding hero Winky is a tiny red dot, wandering through monster-infested hallways where we can only see the outlines of rooms and clearly delineated entry points:

The Experience

When Winky enters a doorway, the view zooms dramatically into the room, where we discover what fresh hell awaits our grinning avatar:

Winky has to pick up the treasure and escape, shooting or avoiding anything that stands in his way, before the game's timer sends one of the wandering hall monsters in for the kill.

Winky has to pick up the treasure and escape, shooting or avoiding anything that stands in his way, before the game's timer sends one of the wandering hall monsters in for the kill.

This Is Your Brain On...

Each door in Venture leads to a new experience -- while each room predictably features a treasure to collect, guarded by monsters or moving obstacles, we don't really know what to expect unless we've visited in a previous life.

The moment when the perspective shifts inward forces a quick and necessary reset on the player's mental framework -- we can't really see what's going on until the new room fills the screen, and by that time we're already in danger. And when we exit the room, any feeling of victory is short-lived, as the perspective zooms back out and we go through another mental reset, immediately dodging the hall monsters again. Winky is always under threat, and the constant travel through doorways means that our brains never quite get to rest.

Adventure games make frequent and varied use of doors -- some doors require us to find a specific key, some "doors" are represented by guardian characters demanding payment or favors, and some constitute logical or mechanical puzzles in and of themselves.

Multiple vintage adventures required the player to slip a newspaper or mat or other flattish object underneath a door, then dislodge the key inserted in the keyhole on the other side (often hinted at only by the player's inability to look through the keyhole), pulling the object back out to claim the prize. Some games featured a lockable "safe room", where the player was encouraged to turn the door to his or her own advantage, securing critical items against thieving NPCs.

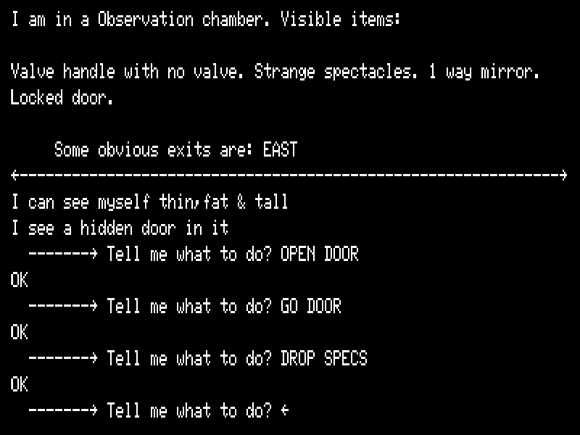

Whether by intent or accident, Scott Adams' early microcomputer adventure Mystery Fun House was already going meta in this regard, with mixed results.

The Doors

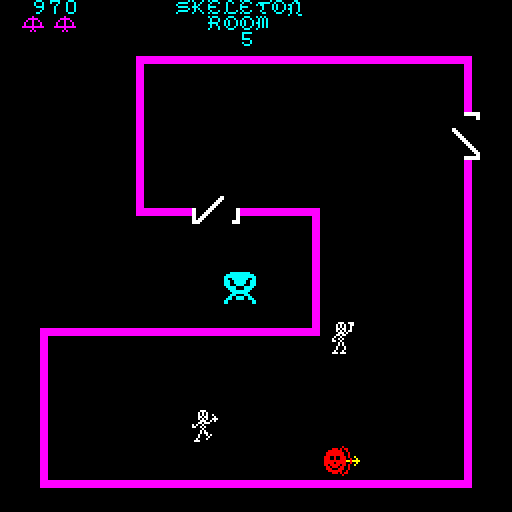

Mystery Fun House takes place in a carnival funhouse, featuring several hidden passageways and a plethora of doors.

The Experience

Some of the doors are hidden and must be discovered by solving puzzles. And some of the doors visibly on display can't be opened at all.

This Is Your Brain On...

While the doors that are functional are satisfying enough, this early game establishes that unrealizable possibilities have an unfortunate side effect. We've spent considerable time exploring the game world and building a mental map of it, graphing out all those places where a closed and locked door appears to be keeping us from exploring new territory. As a result, the game's finale is somewhat abrupt and unsatisfying -- even though we've won according to the designer's rules, our brains are left confused and vaguely frustrated, thanks to those nagging unopened doors. Real life provides little enough closure in the emotional realm, but humans have evolved to believe that any space we inhabit will eventually reveal its geography; a game that confounds that expectation just feels wrong somehow.

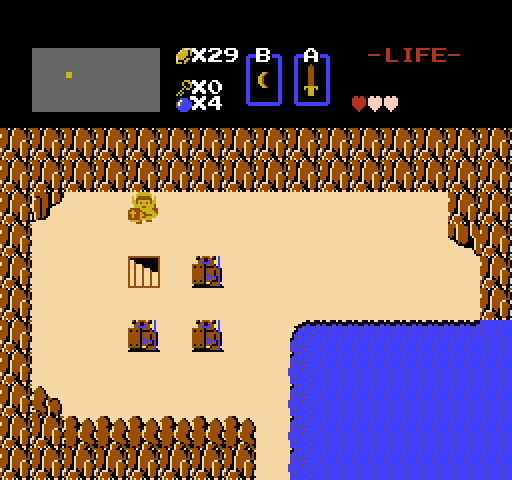

Shigeru Miyamoto's seminal fantasy game features numerous stairways and dark passages, and its gameplay celebrates exploration.

The Doors

The world above ground and the dungeons below complement each other, and both feature hidden paths waiting to be discovered. Our hero Link can push stones, burn trees and kill enemies to find doors, and use bombs to blow holes in dungeon walls to create new pathways, often suggested by suspicious "holes" in the official map.

The Experience

Unlike most of its action-oriented peers on the 8-bit NES, The Legend of Zelda encourages and expects the player to experiment, to try things that might just produce an unexpected result.

For instance, there are six identical armored enemies in this room that can be awakened and fought, but only one of them happens to be concealing a stairway to special item shop:

This Is Your Brain On...

Humans have been globally successful in part because we are willing to take risks and learn from our results -- we can surmise that, at some point in our species' pre-history, somebody took a successful chance and ate an egg, and somebody less fortunate swallowed cyanide. Miyamoto's design capitalizes on our chimpanzee brain's need to goof around and just see what happens.

"Doors" in the Zelda universe are not always obvious barriers, and they may not even be visible until some sort of puzzle is solved. But they do provide structure to the experience, and more importantly they often materialize to reward us for trying things out at random.

For all the memorably choreographed setpieces in Capcom's original Resident Evil -- zombie dogs crashing through windows, that first encounter with the snacking undead -- most players' memories are also filled with...

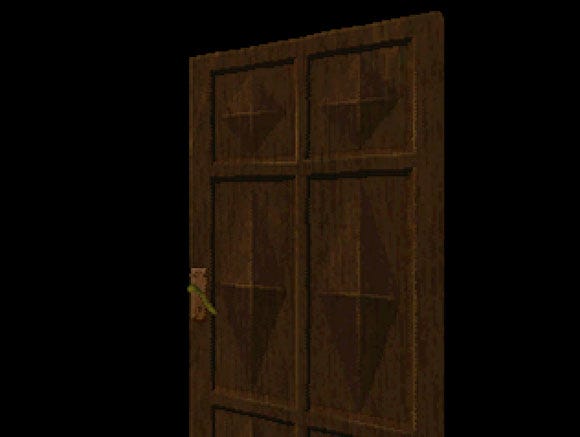

The Doors

Rendered in polygonal 3D, and used primarily to cover substantial loading times on the original PlayStation, numerous animations of opening doors serve to prepare (or disarm) the player for what lies beyond.

The Experience

Some doors require us to find keys, or perform puzzle-solving tasks in the old-school tradition. And the first time we pass through any given barrier, we don't know whether the other side will be eerily quiet and still, or bring us face-to-face with a shambling animated corpse. As a result, this simple, utilitarian moment kicks the suspense up a notch every time we see it:

This Is Your Brain On...

This Is Your Brain On...

Mirroring, perhaps, the realities of our ancestors' mental framework, we're never expecting a radically new experience when we pass through a door in the old mansion. But our brains are clearly preparing for an unknown and very likely dangerous environment on the other side. The effect is heightened by the game's ponderous loading times -- seconds for the door to appear, seconds for the animation to play, more seconds for the fade out. By the time we're back in control, we're paranoid from the sheer suspense. The effect of passing through any specific door wears off over time, as once we've been through, our mental map is populated and we know where we'll be when we get to the other side. But on occasion Resident Evil takes sadistic advantage of this, and we find out that dangerous changes have occurred while we were away.

Super Mario 64 brought Nintendo's hero into full 3D, and much of the joy in its gameplay comes from Mario's unfettered ability to roam around the world, leaping and swimming and climbing trees.

The Doors

Once we've tired of exploring the playground outside and entered the castle proper, we find ourselves in a world of doors, and paintings that serve a similar function, as Mario is free to open or leap into them and enter the worlds beyond.

The Experience

The doors in Super Mario 64 serve as boundaries between worlds, and Miyamoto's inventive design throws us into new experiences as we pass through each one. We are also given reasons to revisit these areas, to complete challenges or locate hidden collectibles.

This Is Your Brain On...

Whether our exploration-hungry brains realize it or not, these portals serve a regulatory function to manage the difficulty curve -- we have to make a certain amount of progress before certain doors will open, though we have a lot of freedom in deciding which worlds to tackle first. When we later return to now-familiar areas, the newness has worn off, but the gateways still serve to bookend each part of the experience -- whether we succeed or fail, Mario gets sent back the way he came in, our framework resets, and we are ready to decide what to do next.

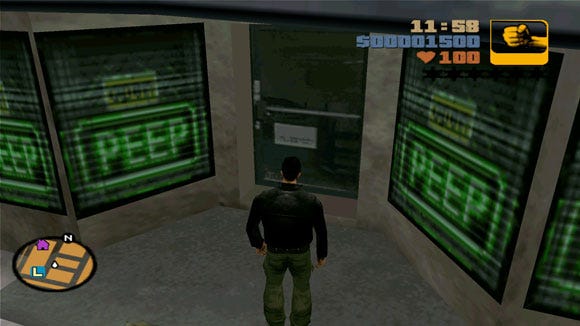

The Grand Theft Auto series came to 3D with its smash-and-grab criminal enterprise gameplay intact.

The Doors

Well...

The Experience

Despite advances in technology, certain limitations afflict the open-world genre even today, and few are so frustrating as the myriad storefronts with sealed doors and opaque windows. We find ourselves standing at one door, forever closed:

And another:

And another:

And another:

This Is Your Brain On...

Why does this kind of thing drive human beings crazy? It's a technical issue, but also a psychological one -- these moments reveal that the illusion of a sprawling cityscape is supported by a bunch of painted boxes, a Potemkin city of substantial but unsatisfying proportions. Almost everywhere we go, we are confronted with intriguing doors that can't be opened. And the few accessible interiors don't really feel like interiors; doors tend to open in our anti-hero's path automatically as we walk into generally indicated zones. GTA III's doors are thus neither obstacles nor points of demarcation; our memories end up depending more on the transitions into canned cutscenes, and the end-of-mission theme music, to delineate the flow of the game.

Sega's attempt to present a realistic portrait of life in a Japanese town in the Dreamcast game Shenmue included engineered detail at a previously unheard-of level, driving the game's development budget to similar heights.

The Doors

Shenmue's doors are many and varied, with sliding paper-thin Japanese doors inside houses, more substantial doors on homes and businesses, and dresser drawers and cabinets that can be opened all over the place.

The Experience

The game's world is largely, naturalistically contiguous, and opening a door only rarely reveals a new experience.

This Is Your Brain On...

As far as our brains are concerned, the net effect of all these realistic doorways is a vaguely unsatisfying and even un-game-like atmosphere. It's possible that the sheer number of doors, drawers, and gashapon machines available dampens the effect; everything starts to seem routine and unremarkable when the player spends so much time on mundane activities like actually opening doors. Moreover, the detailed design is so laid-back that it provides few truly exciting moments when we make the transition from one part of the map into another -- so while we continue to forget why we're here and what we're doing, there's nothing to provoke a rush of new neurological activity either.

Valve's physically impossible first-person puzzler plays with our perceptions in fascinating ways.

The Doors

The player has great freedom -- we're allowed to create passageways from any visible part of the world to any other, by means of the Portal Gun.

The Experience

There's something very weird but immensely rewarding about walking through a hole in one wall and coming out through another hole in another wall, as we make our way toward the exit of one level and on to the next.

This Is Your Brain On...

Oddly enough, while Portal messes with our perceptions in many unique and fascinating ways, the portals themselves don't seem to elicit the doorway reset response from the player. This may be because we are never truly entering an unknown space; we may be walking through physically impossible passageways to get from one area to another, but we are always acquainted with where we are going, even if we've only seen it from a distance.

But Portal does elicit a doorway effect whenever we reach an end-of-level elevator -- these sequences cover loading time and support the game's storytelling, giving the inimitable GlaDOS time to comment on the proceedings. They also give our brains a moment to prepare for the next trans-dimensional challenge.

The Doors

Surprising Fact: There's not a single traditional, clearly-marked point-of-demarcation door in Arnt Jensen's art/puzzle platformer Limbo.

The Experience

There are obstacles and gates, of course, and there are checkpoints between puzzles -- but we're never quite sure when we've reached one, at least until our avatar dies and gets sent back to it.

This Is Your Brain On...

Limbo's lack of obvious structure contributes to the game's eerie stream-of-consciousness feel; there are discrete events, to be sure, but the design doesn't segment the game experience into clear or consistently sized chunks from the brain's perspective. The game is more linear than a dream, but it's intentionally just as disorienting. We only see the boundaries when we have failed, and as there's no going back, our brains simply reset and deal with whatever's at hand; our lizard brains never quite clue in to the fact that progress and death are treated much the same.

As previously noted, adventure games have historically made effective use of doors as puzzles, but Telltale Games manages to up the ante with a remarkable level of tension in the game's fourth episode of season one of The Walking Dead.

The Doors

An abandoned house serves as temporary refuge for the characters, and our protagonist Lee must clear the ground floor by checking out several ominous closed doors.

The Experience

The implementation is deceptively simple -- we click once to direct the player's character Lee to open a door; he readies himself and his gun to face whatever lies behind it, and we have to click a second time to actually open the door.

This Is Your Brain On...

All of this activity seems to fly in the face of modern, friendly game design -- why force the player to click twice when a single click would do? -- but it all has to do with player emotion. The game's established context suggests to our brains that we shouldn't be too sure about opening any strange new doors. Emotionally, we aren't quite as ready for the unknown as we would be in a friendlier context.

It therefore takes a certain amount of bravery to go ahead with that second click; by simply forcing us to prepare mentally to open the door, to really commit to doing it no matter what the consequences may be, the design ups the ante tremendously.

At these moments, our brains are prepared for the worst -- and even when there's nothing of note behind the door, the tension doesn't drain away as immediately as we might like. Our brains remain prepared for something to go terribly wrong, and each door we have to open presents a new psychological challenge.

What can we learn from these examples and counter-examples? A general conclusion is that doors -- portcullises, wormholes, transporters, whatever form they may take -- mean something natural and specific to the human beings out there in the gaming universe.

From a game design perspective, the act of opening up a door can be rewarding in and of itself. The very presence of a gated passage suggests that the player should put some effort into trying to open it. And when, as human beings proxied to a visible or imagined in-game avatar, we go through a door to a new section of the game world, we are effectively resetting our brains and preparing for a new experience.

As a counterpoint, we might suspect that if the player goes through an in-game door, especially one that suggests wondrous things beyond, and does not discover something new and interesting, he or she may be vaguely or explicitly disappointed in the designer's work.

A secondary but more far-reaching implication is that a design approach that mirrors the way our human brains work, not pandering to but respecting our animal predilections, may lead to solutions that seem comfortable and "natural" in a game structure or interface. If there's a door, it should denote some sort of boundary within the experience. If the experience shifts radically without some sort of milestone to let the player reset and prepare, the player may feel disoriented or overwhelmed.

A corollary of the "doorway effect" is that in-game signposting will be most appreciated when it helps the player work around natural human limitations -- Where am I again? What am I trying to accomplish? -- and get back to the task at hand. Having twenty different NPCs yammer on about the game's primary objective or the author's deeply fleshed-out backstory isn't very helpful when the player is lost and confused. A mechanism that reminds the player about the current MacGuffin at hand, especially when life intercedes and the player has been away for a while, can make the difference between a game that gets played to completion and an experience that stalls out after the first few saves.

Doors are a venerable human construct, seen in every culture that has left a historical record behind. Buried deep in our evolutionary history is a belief that opening a door moves us forward into new places and experiences, but our brains also tend to get a little bit lost when we do so. Game designs that recognize and accommodate these basic human needs and tendencies are more likely to provide rich and rewarding human experiences.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like