Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

In the following article, I'm going to talk about the purpose of the creep camp, how various games have implemented them, and what makes a good creep system.

This post originally appeared on Wayward Strategist.

I’ve been thinking a bit lately about a system included in a relatively high-profile cross-section of real-time strategy games: the so-called “creep camp”. When I think about creep camps, I mostly think of Warcraft 3, the game that popularized the term. But they also appear in Halo Wars 2, Ashes of the Singularity, Etherium, Sins of a Solar Empire… even the Age of Empires games had animals that could be considered in the category of ‘creeps,’ with Age of Empires 3 having a unique class of creep units. The now-cancelled mech-builder RTS Servo had a pretty extensive creep selection as well, as did classic RTS series War Wind.

I’m honestly not sure what any segments of the larger RTS community might feel about creeps, but I’ve been all over the map regarding their implementation. In Warcraft 3 they felt like a frustrating but interesting mechanic, requiring a little more multitasking than I felt comfortable integrating into my gameplay. In War Wind, the animals felt like an integral part of the game, adding an element of randomness and skill while deepening my personal relationship to the game’s world. Regarding the rest of the games I mentioned… Well, that will require a bit more of a look into the phenomenon of the creep.

In the following article, I’m going to talk about the purpose of the creep camp, how various games have implemented them, and what makes a good creep.

In Warcraft 3, lategame base expansions are almost always held by relatively strong creep camps.

In Warcraft 3, lategame base expansions are almost always held by relatively strong creep camps.

I really wish there were a better common term for this sort of thing, but if there is I'm not aware of it. The term "creep" seems to come from official common name for hostile neutral enemies in Warcraft 3. MOBAs and other RTS have picked it up, of course, making it a cross-genre terminology. But I find the term itself intensely dissatisfying. However, it's what we're stuck with for now, so I guess I'll have to go forward with it.

I always like to start by defining my terms. In short, an RTS can be said to have "creep camps" or "creeps" if it includes multiple of non-player controlled entities on multiplayer game maps. Typically, these entities are hostile, meaning they attack either team's units when they stray too close. Sometimes, the creeps won't attack until they themselves are attacked. Also typically, creeps have some sort of strategic or tactical significance within the context of the match.

All of this this doesn't really do anything to the question of why a designer would put these things in multiplayer in the first place. Plenty of RTS work just fine without them, after all.

I'd like to propose a number of answers to the question of the utility of creep camps. It's likely that experienced game designers, or perhaps more astute enthusiasts than myself, would be able to come up with a more comprehensive list, but I think the following points will do the topic justice at a high level.

AirMech maps often have a plethora of aggressive creeps that can damage or destroy armies or even AirMechs themselves until they're cleared out. Many base locations are also held by creeps, which must be cleared before the player can claim ownership of the base.

AirMech maps often have a plethora of aggressive creeps that can damage or destroy armies or even AirMechs themselves until they're cleared out. Many base locations are also held by creeps, which must be cleared before the player can claim ownership of the base.

First and foremost, creep camps serve as a pacing mechanism: this is the most common aspect of creeps across pretty much all games that utilize them. They force the player to spend time and resources accomplishing tasks such as freeing up points of tactical and strategic interest. Using Warcraft 3 as an example: most base locations and neutral shops are guarded by creeps, which forces players to build up their forces to a sufficient amount before they're able to liberate those ares of the map (or wait for their opponent to do so and capitalize on their opponent's hard work). Sins of a Solar Empire and AirMech are other easy examples. In Sins of a Solar Empire, Militia fleets block many routes around the solar system maps, forcing players to defeat them before utilizing the various planet locales and harvesting their resources.

Creep camps can also be an incremental and active economic control mechanism. Disposing of creep camps puts additional mental strain on players, which can impact their build order and overall economic timings. Units, especially workers, lost to creep camps, can put a player behind economically. A great example of this are the animals in Age of Empires games: lions and alligators prey upon common food sources such as gazelles, and villagers can run afoul of them if the player isn't careful. Elephants are not naturally aggressive, but take around 5 villagers to hunt without losses.

Given how constrained a resource food can be in general in Age games, making risky decisions about acquiring additional food early has the potential to pay off big time or put the player behind in a painful way, but the game provides the player the freedom to take these kinds of risks and reap the consequences. The Age of Empires series is a prime example of an excellently-designed creep system. All of the active choices surrounding food and its acquisition, especially in the early game, is actually one of my favorite parts of the series.

Creep camps can also force the player to think about map traversal. In games like StarCraft, it's pretty common to simply attack-move across the map in most cases. But Dune doesn't let players do this, with potential sandstorms and Shai'Hulud as real dangers when traversing the map. AirMech's maps are littered with neutral enemies, many of which are fatal to an unwary player. Natural obstacles (natural obstacles, there's an article topic for another day!), including and especially hostile ones like creep camps, can force the player to be more aware of their actions in the game, and can punish sloppy tactics like deathballs. AirMech and Sins of a Solar Empire are both great examples of this, killing unwary players' units with ease through the early game and into the middle of matches.

In Ashes of the Singularity, creeps are mostly an early-game pacing mechanism that has a dampening effect on how quickly and efficiently players are able to take territory

In Ashes of the Singularity, creeps are mostly an early-game pacing mechanism that has a dampening effect on how quickly and efficiently players are able to take territory

Creep camps are also often an early-game incremental tactical success mechanism and opportunities for high risk, high reward behavior. Players must invest limited resources: time, units' hit points, energy, mana, et cetera into clearing out or monopolizing on the resources represented by these units, and the efficiency with which they can handle them can have a profound impact on the course of a match. This is true across most RTS - creep camps, by definition, take some degree of armed force to dispatch, and losing a unit to a creep camp in the early game can easily set a player in a precarious tactical and economic position.

War Wind is actually a really great example of how RTS can implement creeps that challenge players along both the economic and tactical axes. They have creeps that disguise themselves as harvestable resources, and attack workers who venture too close. There are creeps that steal resources from the players' town halls, and return to steal more until they're killed. There are creeps that disable nearby vehicle units, and weak creeps that are aggressive, but summon stronger, passive creeps when attacked. The game is rife with natural hazards that the player must overcome, and the degree of efficiency with which a player handles the world around them has a significant, though not necessarily game-deciding, impact on their outcomes in-game.

Lastly and most importantly, creep camps can be stores of unique resources (or other unique assets/advantages). This is, as near as I can tell, the least common aspect of creep camps, but for me it is the most interesting. Warcraft 3 is another easy example here, with creeps being the primary early-game method for delivering experience points to hero characters. The early game in Warcraft 3 is highly dynamic because of this, with players having to go out onto the map in order to level up their hero, balancing that need for the 3rd resource that is experience against the needs to build structures, harvest gold and lumber, and train an army. Warcraft 3 takes this a step further by leveraging incremental tactical success in a big way: losing a unit to an early creep camp, or improper army control in general in the early game, can turn pivotal early battles against a player, making efficiency in farming creeps an additional critical skill to master alongside build-order efficiency, army control, and hero/spellcaster mana usage.

Creep camps in Warcraft 3 are a highly dynamic subsystem that has profound effects on the gameplay of multiplayer matches.

Creep camps in Warcraft 3 are a highly dynamic subsystem that has profound effects on the gameplay of multiplayer matches.

I already spoke briefly about the importance of food in the Age of Empires early game, but it bears repeating in this context: there are many ways to gain food, and challenges that must be navigated whether the player is gathering berries or hunting gazelle or fishing. Challenges like lions and Elephants add an exciting element of risk and reward and player choice in the early game, while things even out with the advent of farming (when the player's attention is increasingly taken up by other things, such as gathering stone and building up a large army). As an aside, Age of Empires' food resource is one of the most interesting systems in all of RTS.

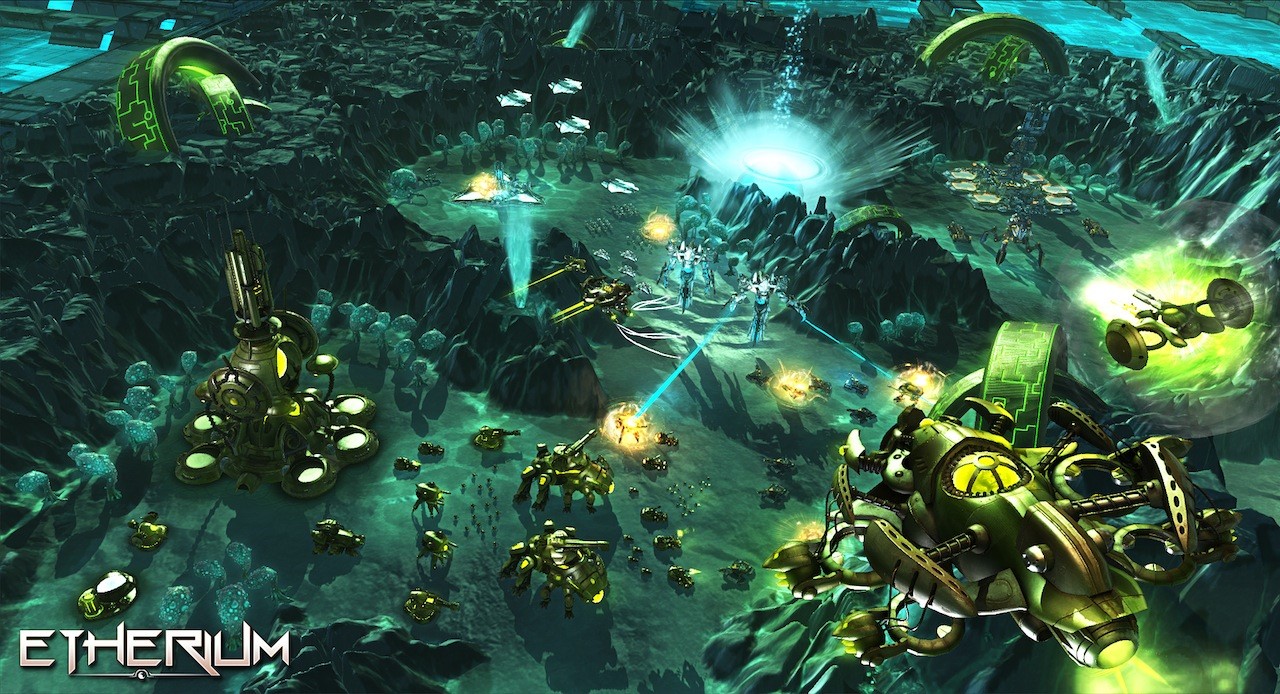

Creeps in Etherium can be destroyed, to take their territory, or can be recruited to fight alongside you

Creeps in Etherium can be destroyed, to take their territory, or can be recruited to fight alongside you

Surprisingly (to me at least), a number of modern RTS have made use of creep camps: both Ashes of the Singularity and Halo Wars 2 feature them relatively prominently in their multiplayer matches, as did Servo prior to its cancellation.

Etherium had an interesting approach with sub-faction/creep hybrids. On some multiplayer maps, there were 1 or 2 very powerful creep camps that took a significant investment to take out. However, these camps could be won over and controlled by a player, using these powerful creeps as supplements to their army. It was an interesting system and a really, really neat approach to both creep camps and sub-factions.

AirMech has some of the toughest creeps around. Most of its multiplayer maps are riddled with turrets, tanks, and AA vehicles that block the pathing of army units and can take down unwary AirMechs that wander into their airspace. While it's more than possible to avoid creeps, it's often important to clear them in order to get armies across the map. It's also quite possible to over-extend while clearing creeps, or to wander into a camp and spend a little too long overhead before flying away, and having to spend a couple of seconds being repaired when your AirMech is brought down by a swarm of Creep missiles.

I've spoken a bit already about Warcraft 3's creep camps. Still probably the gold-standard for Creep implementation, Warcraft 3's creep camps add incredible depth to the game, forcing players out onto the map early, being the primary repository for a unique resource type (Xp for hero characters), and providing some randomization in the form of item drops. They're a huge challenge in the early game, and progressively more difficult camps keep the challenge alive into the mid-game. There's a huge risk-reward and efficiency element involved in taking them down, and they're overall just a phenomenally implemented system that is still pretty much unmatched even roughly 15 years after the game's launch. Bravo, Warcraft 3

Ashes of the Singularity includes creep camps around its tactical territory nodes. To me, they feel more like a speed bump than anything. They provide some important pacing controls in the early game, when army sizes are still small, but into the mid-game (and once players start reaching the maps' VP nodes) they're hardly noticeable. Their implementation makes me wonder at the feasibility of such systems at the scale of games like Ashes or Supreme Commander: these games' scale already imparts so much incremental success and failure as it is.

The Dune RTS games could likewise be said to have ‘creeps’ of a sort, with sandworms occasionally roaming maps’ sandy areas in search of units to consume, and indeed often summoned by armies traversing between rocky plateaus that make up the game’s safe zones. The presence of Shai-hulud on the map makes army traversal between player’s bases a somewhat more fraught experience than in other RTS, since it’s possible to lose units to the great beasts. At least in Emperor: Battle for Dune, some sandworms can be attacked and driven off while others will just spring from the sand, wrecking whatever happens to be standing at their point of emergence. Almost akin to weather events (snowstorms from Company of Heroes 2), the Sandworm is something that is dealt with as an obstacle more than utilized to leverage an advantage, making it somewhat different to many of the other examples I’ve given in this article.

Halo Wars 2, Sins of a Solar Empire and the Age of Empires games also include creeps of one form or another. I already spoke about War Wind, as well.

Hostile Mercenaries in Sins of a Solar Empire guard other planetary systems: a notable obstacle to expansion in the early game.

Hostile Mercenaries in Sins of a Solar Empire guard other planetary systems: a notable obstacle to expansion in the early game.

So, creep camps tend to be used as ways to influence pacing. This is a good baseline for starting to think about their inclusion in an RTS. Would the game benefit from players being restricted in pathing around the map in the early game? How and why? What are the benefits of having players unlock points of interest via combat? What benefits are worth the risk of causing some players frustration when encountering creeps while scouting, fleeing the enemy, or just attempting to contest the map? Being able to provide answers to these questions is vital to understanding the value of creeps, either in an existing game or in one that is currently in development.

But pacing control is really the low-hanging fruit of the utility of creep camps. Destructible debris or other terrain features (mud, snow, and ice terrain types in Company of Heroes 2 comes to mind) can also influence how players approach map traversal and impact game pacing throughout the course of a match, after all. If all you're looking for is pacing controls, a variety of other options exist and can be implemented more seamlessly.

Ideally, creeps should serve a larger purpose in a game than pacing. Creeps should improve the amount of player interaction with and control over the outcome of a game system, and include elements of risk/reward beyond those already in the game. Something as simple as predatory animals in Age of Empires, or creeps being the most efficient store of XP in Warcraft 3, has a profound impact on the nature of those games, specifically in the earliest stages of a match. And it's the early game that typically has the most need for nuance, pacing, and most rewards players who take risky steps to get ahead. Aggressive creeping can put a player behind economically or in army size in the short term in Warcraft 3, but higher level heroes will quickly start to pay off over the course of a match.

Obviously, these systems don't have a place in every RTS, or even in the vast majority of games in the genre. Any type of creep would likely feel out-of-place thematically and mechanically in a game like Company of Heroes, Dawn of War or Act of Aggression, but there's a case that Homeworld could implement them relatively seamlessly. Likewise, Ashes of the Singularity and Halo Wars 2 might not miss their creep systems, were they removed from those titles. There's no simple answer to the inclusion of creep camps, since the best of them are integral to their game's systems in non-trivial ways.

I hope, however, I've been able to shed some light on why the good systems are good, and have provided some interesting food for thought.

If this article had a point, it's simply that creep camps are an interesting mechanical system used by some games to a variety of tactical and strategic effects. The best such creeps, as evidenced by Age of Empires, Warcraft, and War Wind, tend to add more to the game than pacing controls: they can provide a variety of powerful risk/reward systems that players can try their hand at, serve as unique strategic targets, add in targeted randomization, and encourage players to interact with the game map in more interesting ways. Hopefully, some future RTS can explore additional ways to add new dynamics to their multiplayer via improvements to creep systems.

Thanks for reading.

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like