Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

A former Capcom USA senior VP talks Capcom's friendly feud with Acclaim, the cultural differences between Capcom USA and Capcom Co., Ltd., in Japan, and Street Fighter versus Mortal Kombat.

The following excerpt comes from author David L. Craddock's Long Live Mortal Kombat, the definitive account of the MK franchise's creation and its global impact on popular culture, funding now on Kickstarter.

The enmity between Nintendo and Sega defined the 16-bit console war of the 1990s, but there were theaters within the larger scope of that grand epic. Mario versus Sonic was one. Street Fighter II's World Warriors against the kombatants of Mortal Kombat was another.

Both pugilistic franchises had their strengths. Mortal Kombat was notoriously violent and flashy. Street Fighter II was mechanically complex. Mortal Kombat's characters and lore evolved from game to game, sequel to sequel. Capcom refined Street Fighter II's basic and special attacks over several iterations. Some of my friends favored one and turned their noses up at the other. I was the peacemaker, bravely crossing the aisle of local arcades or living rooms to proselytize my "Why not both?" style of thinking. (Although I confess I preferred MK's grittier aesthetic and more aggressive style of play.)

If you were the purveyor of either franchise, you couldn't afford to adopt that mentality. At least that was my thinking. In researching Long Live Mortal Kombat, I asked my contacts from Midway and Acclaim, which brought MK1 and MKII to home platforms, for their thoughts on Capcom's prizefighter. Their line of thinking was, to paraphrase, that SFII was good, but Mortal Kombat was a different beast. Starker, and in possession of characters that players actually cared about as co-creators Ed Boon and John Tobias spun yarns from game to game. Look at the attract mode—those demos that played when no players were around to feed machines quarters—and you got sucked into Mortal Kombat's supernatural world. Street Fighter II's attract mode revealed such scintillating details as Ryu's height, weight, and blood type. Riveting stuff, but it got me thinking: What did Capcom think of Mortal Kombat?

Mario versus Sonic, Command & Conquer versus WarCraft II, and Street Fighter versus Mortal Kombat. Just a few of the video game rivalries that defined the 1990s.

The answer is googleable, and google it I did, but I wanted to talk to someone who was on the front lines of one of the hottest battles that continues to this day—and one that, in the '90s, had a major impact in the conflict between Sega and Nintendo.

Enter Joe Morici, the senior vice president of Capcom USA during one of the company's most pivotal eras. I knew of Joe through an anecdote shared with me by Acclaim co-founder and president Rob Holmes, who smiled gleefully as he recalled buying all available ad space in an issue of Capcom's Street Fighter II comic and plastering it with advertisements for Acclaim's forthcoming Mortal Monday, a $10 million marketing blitzkrieg that saw the first MK arrive on Super Nintendo, Sega Genesis, Game Boy, and Game Gear weeks before Street Fighter II hurricane-kicked its way onto Sega's 16-bit console for the first time.

Joe and I talked Capcom's friendly feud with Acclaim, the cultural differences between Capcom USA and Capcom Co., Ltd., in Japan, and, of course, Street Fighter versus Mortal Kombat. (Spoilers: He's a Street Fighter soldier.)

David Craddock: How did you get involved in the video game industry?

Joe Morici: I'm dating myself, here. I worked for a company initially called Universal USA. which [made games such as] Mr. Do! and Mr. Do's Castle. They had a job offering in the newspaper. I was working as a vice president in banking, which I hated. I went and interviewed with a guy named Mac Sugita, who was the president of the company, and I got the job as a regional sales guy. That was the early 1980s. Universal USA was a small Japanese game manufacturer that was from Tokyo. A guy named [Kazuo] Okada-san owned Universal.

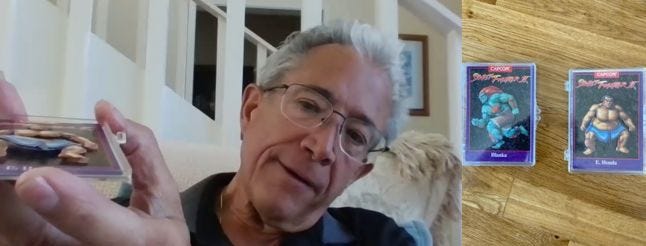

Morici shows off his custom-made Street Fighter II cards designed by artist Denny Moore. Moore used layers to make them appear three-dimensional when viewed at an angle. (Photos courtesy of Joe Morici.)

Craddock: How did you make the jump from Universal to Capcom USA?

Morici: At Universal, we were having trouble getting distribution through the different arcade distributors across the country. There was resentment or hesitation to buy Japanese products 80s, so we opened up our own distribution company. We had four offices. I started that division because I started calling on the operators directly and bypassing the distributors, so we became our own distributor, Universal Distributing Company. We would grey-market games in from Bally, Sente, all the different manufacturers. We were hurting other distributors' business because I was doing it and I was having pretty good success. Sugita leaves, and George Nakayama comes in to run Universal. A guy named Will Laurie, who was the president of Bally Advance in San Francisco, called me and said, "Let's go have lunch." He made me an offer to go to work for Bally Advance as the sales manager. They offered a $25,000 raise. I went back to George and said, "If you match their offer, I'll stay." He said no.

I left Universal and went to work for Bally. I was the youngest guy there by far. I was managing a bunch of older gentlemen. Bally handled everything: coin-op, cigarette machines, any sort of vending machine, pool tables. I was there for a few years. At that point, Nakayama [had left Universal and] was the president of Capcom, USA. He calls me on the phone and he says, "I want you to work with us." I said okay, but I knew a guy named Ron Carrara, who was a good friend of mine, and who was running Bally Advance [following the departure of Will Laurie], write me a letter that gave me a $25,000 raise. I took that letter back to Nakayama and I said, "You match this offer, and I'll work with you." He did, so I got the $25,000 raise twice.

I joined Capcom and became the regional sales manager of Capcom coin-op, because there was no Capcom consumer branch. We released a bunch of coin-op games, and one was Street Fighter. Do you remember the first one with the rubber mallets?

I told the marketing company, " Look, typically, we don't go against competitors this way, but—go against Mortal Kombat. I don't really care what you do, just show Mortal Kombat getting crushed."

Craddock: I do, yeah.

Morici: We took it off the market because people were getting hurt. That's why we put the buttons on there. Nintendo was getting started [in the video game business], and George Nakayama asks me, "Would you want to run the consumer division?" I said, Yeah, okay, fine. Why not? I mean, I knew deep down that the coin-op industry, once Nintendo got stronger, would be pretty much nonexistent. But back then, the coin-op business was huge. There was an arcade game in every corner store, every laundromat, because they were making good money. Street Fighter was making well over $1,000 a week. You're talking $4,000 a month [per cabinet]. That's a lot of money for one game.

I start the consumer division, and it was just me at first. I started hiring people, regional sales guys, across the country. Most of them were independent salespeople because the [consumer games] industry was new, so we [Capcom USA] were one of the first licensees of Nintendo. It was us, Bandai, Namco, and Konami. We started selling games. The first ones we had were conversions of Ghosts 'n Goblins, 1942, Commando. These were great coin-op games we converted over to the consumer division, which was what Capcom did. We were using the coin-op business as a testing ground for the home market. The thinking was that if a game did well as a coin-op, it would do well as a consumer title. That's really what happened.

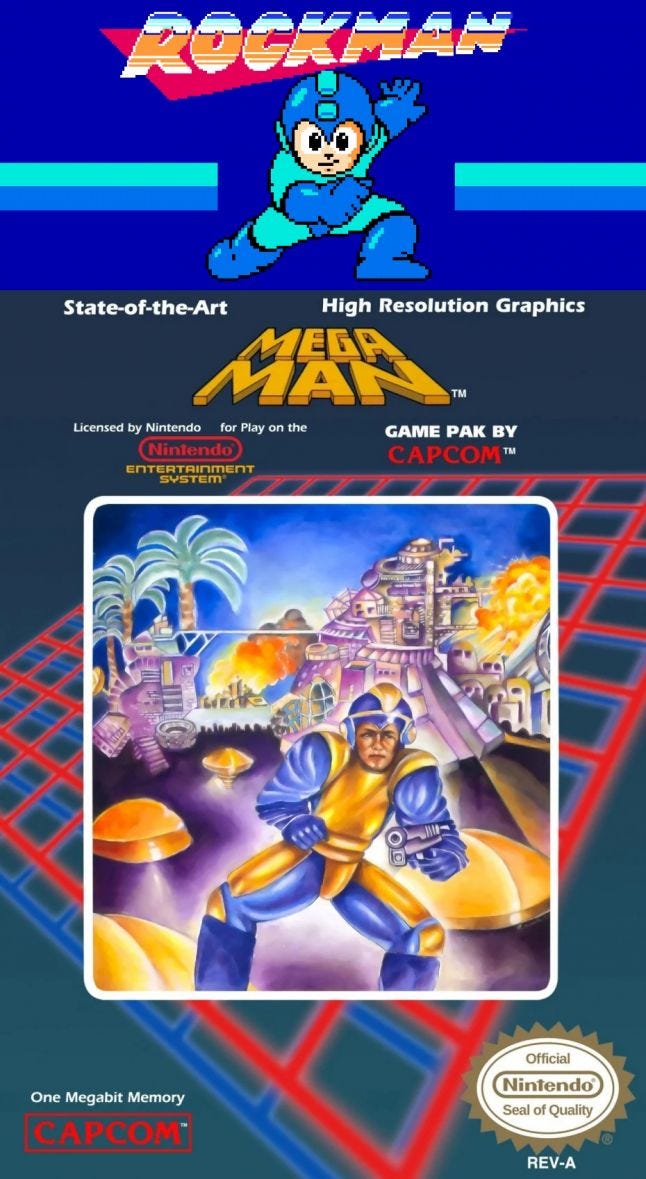

This was before the Street Fighter II phenomenon, and before Mega Man. That's the game I get grief about all the time for changing the name. That didn't make sense.

Mega Man's name change took time to sink in. The original game's box art still hasn't resonated.

Craddock: I've always wondered about that. What was your motivation for changing the character's name from Rock Man to Mega Man?

Morici: Rock Man came over and I thought, Rock Man doesn't make any sense to me. I knew the characters were based on rock musicians and stuff, but I thought, Let's just change the name. At that point, Capcom [Japan] trusted me to do the right thing for the US market, so I changed the name to Mega Man. It really wasn't this long, drawn-out discussion with everybody in the office. I just said, "Yeah, let's change it." So we did. I don't know why people get so upset about it. It just made sense to me.

Capcom USA was Capcom's biggest customer. They made us buy our product from Japan. I said, "We're the same company. Why are you trying to sell me product?"

Craddock: I prefer "Mega Man." It's a stronger, superhero-sounding name.

Morici: Yeah. It just came to mind. There wasn't a lot of thought to it. It was, I like the name Mega Man. It's big, grandiose. But if you remember the first Mega Man game's box, it looked like hell. The reason it was so bad was because we had literally 24 hours to turn it around. Nintendo said, "We need we need your artwork by tomorrow." Somebody worked all night long to come up with this garbage-looking box, and then we released it because we had no choice. The first Mega Man did okay, then subsequent Mega Man games continued to do better and better and better.

Craddock: At other companies such as Atari, there was competition between the coin-op and consumer divisions. Was that the case at Capcom?

Morici: Oh, there was always competition, always, always, always. But as the consumer group, we were a larger portion of the revenue. There really wasn't much they could say. We were doing, like, a hundred times more than they were doing. At one point, took over the coin-op division and was running consumer. Japan asked me to do that because—how can I describe it politely?—there was some graft and corruption going on, on the coin-op side. I knew about it because I had an informant who told me what was going on. I fired the whole staff. Management was gone, too, and I took over that division. This was during the time of Street Fighter II Champion Edition, and we were selling thousands and thousands of coin-op games.

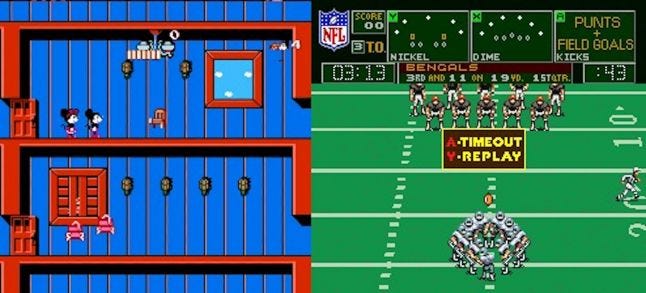

Our coin-op games were good, but they were all the same types of games, basically. That's when I thought, Let's get some games for kids. Walt Disney didn't have any distribution in console games. They had computer software, but not anything for Nintendo. I flew down to see Shelley Miles, who was the head of that division, and negotiated deal with her to sell Disney games for Nintendo systems. They were an exclusive rights until we started making a lot of money for Disney. Then they branched off [and developed games internally].

The first game we came out for Disney was Mickey Mousecapade, which was the worst. It's terrible. Minnie's just following Mickey while he's jumping around. But we sold a lot of units, well over a million, which at that point was a big number. Disney was getting a huge royalty because we paid them royalties on every game we sold, and they did all the artwork for us, too, which was phenomenal. That was part of the deal. They were all hand drawn. There were no computer graphics at this point.

Left: Mickey Mousecapade, the less-than-auspicious start of Capcom's revered Disney Afternoon catalog of games. Right: Capcom's MVP Football for Super NES.

Craddock: Do you have any artwork from those days?

Morici: I have a few things. I have a Street Fighter trading card with Honda on it. The guy [Denny Moore] who did the artwork for me, it's all hand cut. There are about six layers, and it has a three-dimensional look. He gave me a couple of these that he did for me. They're one of a kind.

Do you know about the code for Mickey Mousecapade?

Craddock: No.

Morici: We had no development costs for it. We named it, and that's about it. We did the packaging with Disney. It was a Hudson Soft product. Hudson Soft in Japan had the rights for Mickey Mouse, but they didn't have the rights for the US. I went to Hudson Soft and said, "We want to pay you a royalty and take your code." That's what we did, and we got the code for nothing. All we had to do was market it, and we sold well over a million units with no development costs. Then we did the Disney Afternoon games, and we did the Disney World Tour, which was I think it was in 20 cities. We had kids come out and play the Disney video games and had a big, final tournament at Disneyland, flew all the kids out. It was a big deal back then.

Craddock: I played all those games. They played great, and the music was incredible.

Morici: Oh, yeah. It was interesting going to Japan. I used to go to Osaka once a month and have meetings with senior management. You'd go into a classroom setting; there were desks, a teacher lecturing at the board about how to program games, music, and different levels. It was pretty amazing how they do it over there, just sitting in a classroom learning how to do it. Of course, back then, it involved more manual work [rather than automated with technology]. Capcom's development team was very strong, and they were only doing Nintendo products. We did Disney products through Aladdin [on Super Nintendo], and then Disney branched out. That's when the other Aladdin [for Sega Genesis] came out, made by Virgin. Capcom wasn't doing Sega development.

What we did instead, which I think was kind of foolish, was Street Fighter II for Genesis was developed by another company in Japan, not Capcom. This goes into the history of Street Fighter versus Mortal Kombat.

Craddock: It also raises a point I make in Long Live Mortal Kombat. For players who remember the 16-bit "console wars," arguments often boiled down to first-party games like Super Mario Bros. and Sonic. The point I make is that third-party titles were becoming increasingly important in turning the tide of that war, if you want to call it that. Nintendo getting exclusive rights to the first home version of Street Fighter II was a big deal.

Morici: [Kenzo] Tsujimoto had a very good relationship with [Minoru] Arakawa at Nintendo of America, and with Mr. [Hiroshi] Yamaguchi in Japan, and we weren't focusing on Sega at that point. We gave them the exclusive for Street Fighter II, which supposedly gave us priority on production thing. I was able to convince them to support the Sega Genesis at that point. I said, "We need to support it because Sega is doing well in the US market." It wasn't doing as well in Japan, but it was doing well here. That's when they started Street Fighter II for Genesis.

Craddock: Even though Street Fighter was hot, I was surprised that Champion Edition launched in September 1993. Was Capcom not aware of "Mortal Monday" and the home versions of Mortal Kombat?

Morici: So, I knew [Acclaim co-founders] Rob, and [Greg] Fischbach, and [Jim] Scoroposki. I knew them very well because back then, the industry was friendly competition. The industry was small compared to what it is today. So, Street Fighter II: Special Champion Edition was supposed to be out in April. The Japanese said, "We want you to fly over to Osaka and look at the game." I went over there and looked at it. Now, Capcom's team wasn't happy with development. I think that was because it was done by an outside company and it wasn't meeting their standards. I said, "To me, the quality is more than good enough to release it in April."

Japan decided not to release in April. They wanted to make it better. It ended up releasing head-to-head against Mortal Kombat. They knew about Mortal Monday, and I have to give Acclaim credit. They had a really good marketing team. They really did. My team was good, but we were a Japanese company, and Acclaim was an American company, and they were managed differently.

Craddock: What did Capcom's developers think of Mortal Kombat?

Morici: They didn't think it was anywhere near Street Fighter [levels of popularity]. Mortal Kombat did very well in America, but it did not do well in Japan. Maybe because it was an American product. We knew Street Fighter II would be a big game [before release]. Everybody knew Mortal Kombat and Street Fighter were in competition, and that Street Fighter was a much better-playing game than Mortal Kombat. Mortal Kombat had the death moves, which got nothing but grief from everybody. That's another story about the politicians.

So, we were going to come out in September. Do you remember the commercial with the guard with a flashlight walking through the game store?

Craddock: I only saw it rather recently when I was researching Long Live Mortal Kombat.

Morici: We came up with a TV commercial. I told the marketing company, " Look, typically, we don't go against competitors this way, but—go against Mortal Kombat. I don't really care what you do, just do something to show Mortal Kombat getting crushed." That's what we came up with [Bianca's hand reaching out from a Street Fighter II box for Genesis and crushing the Mortal Kombat box next to it.] Rob Holmes calls me and goes, "You're such an asshole. Why'd you do that?" I'm like, "Well, what the hell? I knew you were coming out directly against us, so we did a commercial."

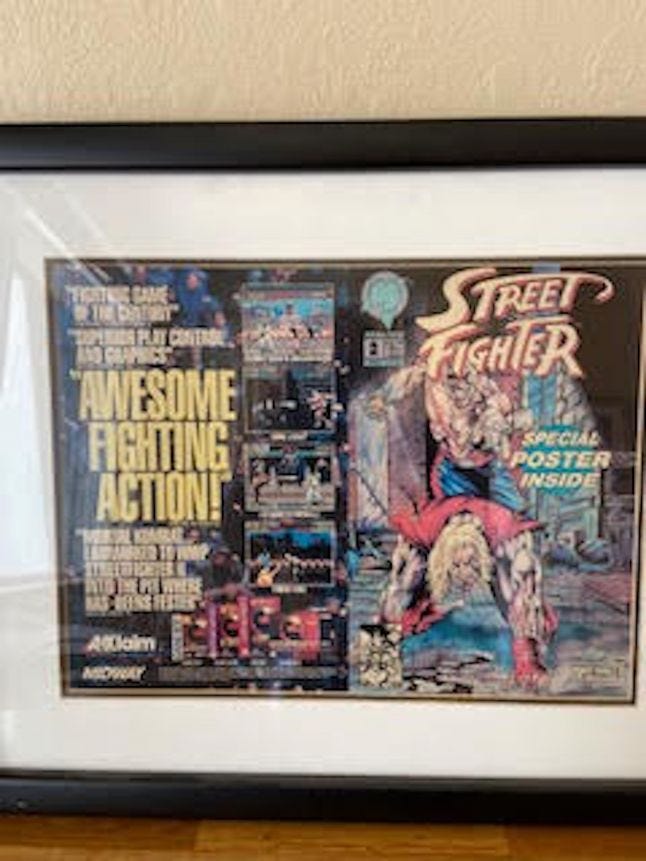

Then Rob sends me a framed Street Fighter comic book with a letter gloating because he took all the ads out for Mortal Kombat in our comic book. [laughs] It was kind of funny, actually. We sold a lot of product, but we would have sold twice as many if we would have released in April. The game was not bad. We had orders for two million units, which was $100 million worth of business back in 1993. We sold approximately 90 percent of those units, but Mortal Kombat, with Mortal Monday and the way Acclaim marketed it, did a better job, I have to say.

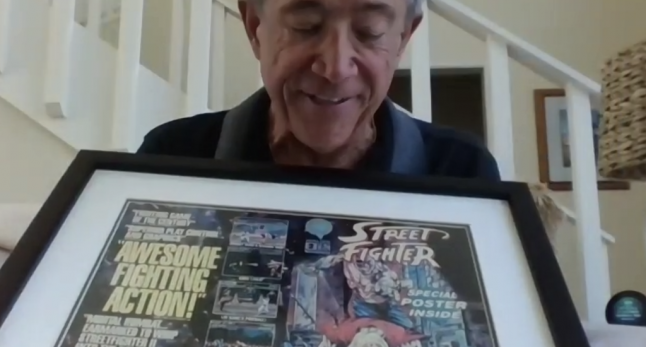

Morici's framed issue of the SF2 comic book co-opted by Acclaim's Rob Holmes.

Craddock: What was the deciding factor in your convincing Capcom to develop for Sega and Nintendo?

Morici: I think it goes back to Special Champion Edition. They saw the quality of the game and thought it wasn't good, and they were perfectionists because their games were usually good. We ended up acquiring small PC game companies, because I wanted to keep our feet in the PC business. We did a few PC games. One was called Pocket Rockets, which was a racing game, which did okay. The PC market was so small, but I just wanted to keep our fingers in it. We didn't spend a lot of money or a lot of effort on it. But we did that for a while. And then Capcom got an NFL football license, and the game [Capcom's MVP Football for Super NES] was terrible because Japan has no clue about how to play American football.

Craddock: Actually, you reminded me: Before I had a Super Nintendo, I really wanted to play Street Fighter II at home. My grandma had a PC with MS-DOS, and I played Street Fighter II on that, but it was terrible. It had two buttons, one punch and one kick, and the characters floated around like they were fighting on the moon. I remember reading that it was converted from the Amiga version.

Morici: Well, that was that I think that was developed in the UK, if I remember correctly. We were licensing from a company called US Gold. We had a deal with the UK to license for the PC market and they would develop it in the PC format. We thought, Well, we'll distribute some PC stuff they developed over there. That version of Street Fighter was just terrible. There was a Commodore 64 version, too.

The maligned Commodore Amiga (top) and MS-DOS ports of Street Fighter II: The World Warriors.

Craddock: Since childhood, I found it interesting that Capcom focused on updating Street Fighter II while Midway was putting out sequels to Mortal Kombat. Obviously Street Fighter II was successful, but was there any concern about keeping up with Mortal Kombat?

Morici: The development time [for an update] was much shorter. That was one of the reasons: It was something they could tweak quickly and release it to the marketplace. Capcom did a really good job at developing that game and then just kind of tweaking things as they went along.

Craddock: What other stories do you have that highlight the differences in culture and business between America and Japan?

Morici: When I met Mr. Tsujimoto, he was pretty much out of money. He had sold Irem and started Capcom, and then he hired the right people to get that company started, like [Tokuro] Fujiwara as the head of consumer games in Japan, and [Yoshiki] Okamoto as head of coin-op. He had a small part in the Street Fighter movie. There's a scene with a crowd of soldiers cheering on [Jean-Claud] Van Damme, and Tsujimoto is one of the soldiers.

Morici shows off his framed comic book.

Capcom had a corporate house in Japan. All wealthy companies have these houses where management goes and discuss things. Ours was a couple-hour train ride from took from Osaka. I was the only American there, and the only one who didn't speak Japanese, but I always had my entourage with me, and they would translate. All these executives were smoking, and Kenzo [Tsujimoto] would be cooking his food, and there were dorm rooms where you sleep. There was a big pool with the Capcom logo at the bottom. We played golf because there was a golf course nearby, and we'd play in the middle of winter. It was snowing, but we'd be playing golf. They all snored horribly, so at one point, I told Tsujimoto, "Move me to the hotel across the street. I'm sorry, but I can't sleep."

Craddock: How did Capcom HQ in Japan view Capcom USA? Were they considered equal partners?

Morici: We were their biggest customer. What they made us do we had to buy our product from Japan. We would say, "We'll commit to X amount of dollars," and they had an export department. To me, that made no sense. I said, "We're the same company. Why are you trying to sell me product?" That's when Japan got in trouble for transfer pricing. The US government didn't take kindly to profits basically being transferred to Japan, which was what Capcom was doing, so they stopped that. We got product from Japan and weren't paying them a huge royalty like we weren't before, which was basically taking the cash and flowing it back to Japan. It was interesting back then.

.jpg/?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

Despite healthy competition, Mortal Kombat and Street Fighter remain the world's most dominant fighting-game franchises.

Craddock: There are a lot of fighting games today, but Street Fighter and Mortal Kombat remain the two top properties in the genre. Why do you think they've lasted so long?

Morici: Well, I don't know about Mortal Kombat. Street Fighter was sort of the first of its kind. Capcom has continued to promote it, and there are things like the animated series. We did all sorts of licensing back then, toy deals and everything else. Street Fighter has been their main franchise. They've had other games that have done really well, like Resident Evil, but Street Fighter made Capcom what it is today.

This excerpt comes from author David L. Craddock's Long Live Mortal Kombat, the definitive account of the MK franchise's creation and its global impact on popular culture, funding now on Kickstarter.

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like