Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

This is the final section of my honors thesis on extended fiction in game design, it discusses games that utilize ludoethical tension in a different and darker manner than previously discussed. It also contains the conclusion to my thesis.

The penultimate non-diegetic element in relation to any game is the player. Already discussed in earlier sections are games that explicitly acknowledge the player as part of the extended fiction, and while these games provide great exploration of interesting narrative and metanarrative concepts, they aren’t exactly searing in their critiques: Earthbound provides an emotionally resonant but not critical view of the player as a savior, Icey provides a playful, thoughtful rivalry between player and developer, and Life is Strange takes into account the anticipated goals of the implied player in order to pit them against emotional attachments to implied being. This chapter will discuss the player in a diegetically ambiguous position, and specifically how ambiguous player- avatar relationships provide deep immersion and critique of the player-avatar relationship. Matthew Weise describes this concept as it appears in metal gear solid as such;

Metal Gear Solid stretches the membrane between the fictional world and the real world as a way of bringing player and fiction together -- not driving them apart. It does this by reveling in the ambiguous nature of the player-avatar relationship. The player is Snake, but not Snake. Snake is the player, but not the player. When characters look at Snake they often see Snake, but they just as often see the player, staring right through Snake's eyes. (Weise)

In other words, an ambiguous player-avatar relationship is a situation in which the player is not explicitly acknowledged as diegetic, but the themes, dialogue, and overall presentation of the game heavily imply knowledge of the player’s presence. More importantly, the responsibility for the events that take place in the game are often ambiguously attributed to the player, implying that the (often horrific) results of the player actions are the fault of the player for interacting in the first place. This is a form of player culpability, or implication of the player as accountable for the actions their avatar takes in the game. These situations are often presented in graphically and narratively surrealistic ways, as was the case with Earthbound’s acknowledgement of the player in its surreal climax. To describe a technique based in surrealism, there’s no better place to start than Hotline Miami.

Hotline Miami is a game about violence, described most commonly as “ultraviolent” (Onyett). The game revolves around the protagonist receiving over-the- phone instructions to clear buildings full of Russian mobsters and following out those orders with a variety of weapons and in the most brutal and stylized ways possible. Baseball bats, golf clubs, machetes, knives, guns, and bare hands are all used to create bright red splatter marks that track the player’s bloody trail through the level. The game induces such a heart-pumping adrenaline rush in its fine-tuned gameplay that any trepidation the player might have about the sickening violence is lost in the thrill of the interaction. The game makes its ultraviolent content fun and satisfying, drawing the player in, making them want more, but then questions why they so thoroughly enjoy the violent acts their avatar commits in the game.

Hotline Miami has an ambiguous player-avatar relationship that makes the player culpable. The player avatar is no hero rescuing a victim in distress, or a vigilante stopping bad guys from doing bad things. Their violent rampages are just that, a bad person killing other bad people, given directions by likely even worse people. The game contains no morality, no redemption; its addicting gameplay is its own reward, and yet the enjoyment of that reward is questioned by the game itself. “Do you enjoy hurting other people?” the game asks (Hotline Miami). “You’re not a very good person, are you?” it states (Hotline Miami). The player is not progressing through the game with a greater purpose or performing horrific acts for a greater good; they are doing what they’re told to do by the game, the only thing they’re allowed to do by the game:

“The only way to truly interact with the world is to kill. Such is the case with many games, yet few call out the inanity of it so bluntly” (Onyett).

Like Manhunt, Hotline Miami forces the player to be culpable, though in a different sense. While the culpability of the player in Manhunt relies on their choices, that being whether they execute more or less gruesome executions for points, Hotline Miami has no such choice. When the game asks, “Do you like hurting other people?” (Hotline Miami), there is no diegetic answer “no” for the player to respond. The only way for the player to respond to the ethical side of the ludoethical tension the game causes is for them to stop playing. Continuing the game makes implies that the player is culpable in the actions their avatar takes, no matter how horrific. Continuation of the game, especially beyond the point where the game declares you “not a very good person” (Hotline Miami), is an admission of complete surrender of the implied being to the implied player.

Another game in this style is Spec Ops: The Line. A game adaption of Heart of Darkness, Spec Ops tasks the player avatar, a generic but likable army captain with venturing into the ruins of modern-day Dubai in an attempt to find the missing John Konrad. This presents a perfect example of the unremarkable character that’s often present in games with ambiguous player-avatar relationships. This type is usually devoid of distinguishing features, sometimes being entirely silent and often never being seen from a third-person perspective by the player in first person games. Captain Walker is a character with voice acting and some personality, but he is a character that provides an easy avatar for a player to identify with, and thus it is more difficult for the player to distinguish between their actions and the actions of their avatar.As the game progresses, Walker and his team are forced into increasingly grisly situations, all seemingly caused by the cruelty of Konrad. At one point, Walker and his team are pinned down by enemy gunfire, and so launch White Phosphorus into the enemy combatants, only to realize when the combat has ceased that they murdered a large group of civilians in doing so. As the game progresses, it’s surrealistic and ghastly imagery seep into even the loading screen messages of the game, with quotes such as “Do you feel like a hero yet?” (Yager) taking the place of what started as helpful gameplay

In the end of the game, as Walker alone approaches Konrad’s penthouse in the Burj Khalifa, he finds Konrad dead, having committed suicide before the story of the game had even began. Konrad’s voice over the radio was entirely imagined by Walker, him being pushed into disassociating the atrocities he committed and blaming them on the imagined Konrad. The hundreds of NPCs murdered over the course of the game were murdered entirely by Walker. As another one of the game’s loading screens states, “The US military does not condone the killing of unarmed combatants. But this isn’t real, so why should you care?”. The game uses the non-diegetic loading screens to explicitly address a non-diegetic player, but the diegetic narrative of the game implies and indicts the player in a much more serious capacity. The confusion of the player, their complicitous in the atrocities committed, all are implicitly attributed to the player. One of the writers of Spec Ops, Richard Pearsy, described the conclusion as such; “When the Delta Squad arrives, Konrad faces exposure and humiliation and takes what he sees as the only honorable way out – suicide. In the end he literally paints a picture of the player's sins, presenting the player with the dilemma Konrad, himself, faced. What have I done? How do you feel about what you have done?” (Pearsy)

The player’s continued interactions with the game implicate them in the results of those actions; the massacre committed by Walker is only enabled by the player’s continued insistence on playing the game, despite the intense narrative ludoethical tension it provides.

One of the most iconic games that examines and comments on player motivation and provides pointed ludoethical tension is Bioshock. Bioshock does this through enthusiastically embracing of the concept of extended cognition, a “theory states that our cognition (or mind) includes not just the brain, but also the body and the surrounding environment” (Cuddy). This feeds into the notion that the character in the game is not a separate entity, controlled by the player, but an extension of the player themselves. Bioshock encourages its player-avatar ambiguity by making the protagonist virtually indistinguishable from the player; the player never sees the avatar’s face, never hears them speak, and the only distinguishing feature the player can find on the character’s model is the chain tattoos on the avatar’s wrists. First-person perspective games will usually involve a combination of voice acting, and cutscenes featuring the protagonist, distinguishing them as a defined character, but Bioshock doesn’t. This is purposeful; the player avatar is meant to be as transparent as possible, removing the buffer between the player and the game world. Bioshock removes almost all separation of player from the avatar, directing the game’s themes and commentary right at the player with all but explicit acknowledgement; there is no buffer between the character’s choices and their avatar’s choices. The actions are not Nathan Drake’s or Jane Shepard’s, they are the player’s actions, and the player’s consequences as well.

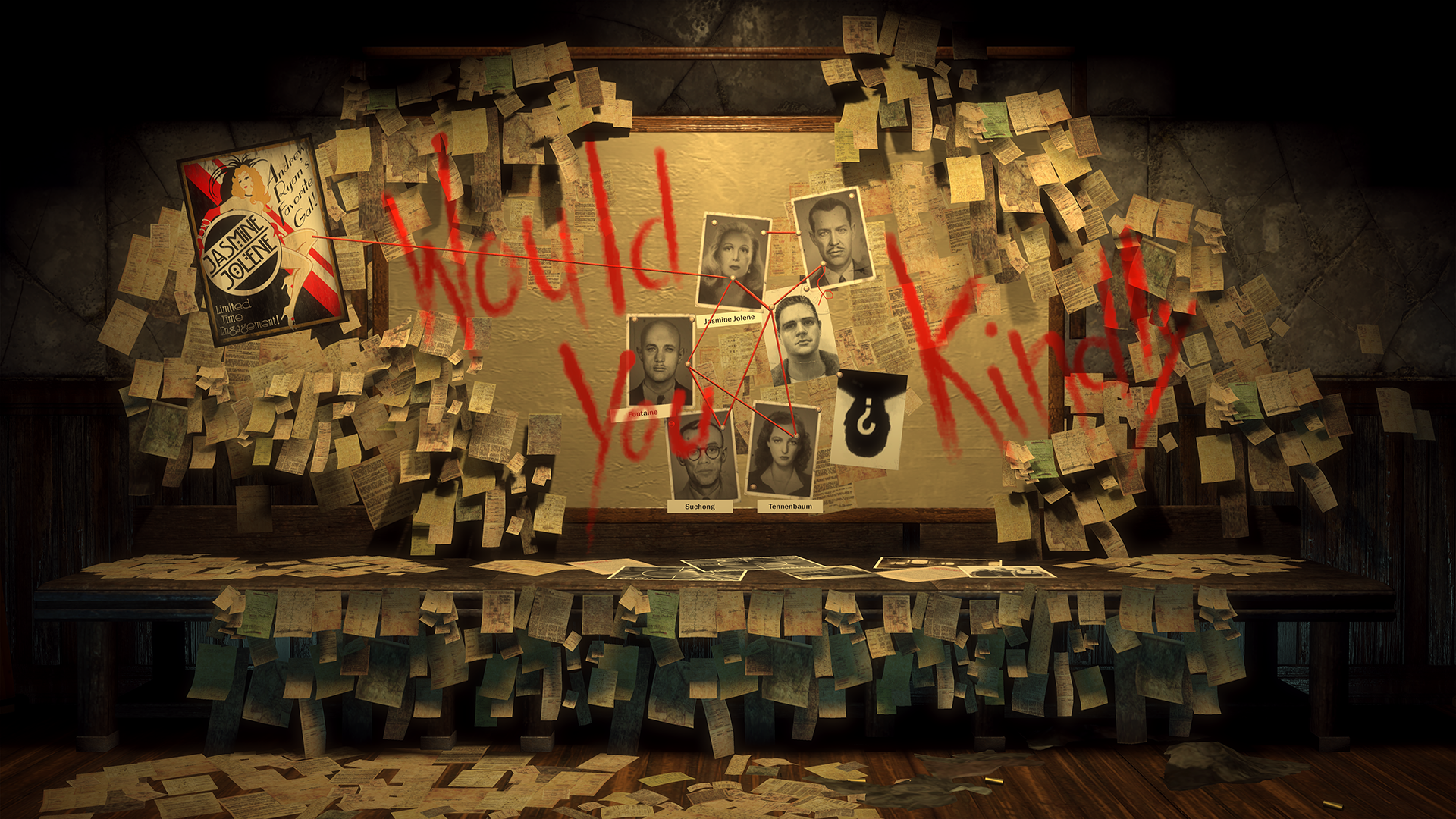

Bioshock’s formula for guiding the player through the game is a common one; the player is given direction over a short-wave radio by a friendly Irish voice belonging to a man named Atlas. This guide, a man claiming to be just as trapped in the city of Rapture as the player’s avatar is, guides the player, giving them direction, helping them through obstacles and leading them towards their eventual salvation, always with a polite “Would you kindly...” before instruction (Bioshock). The game even offers convenient notifications of the next step in the players quest to clearly convey all the necessary information.

Bioshock’s twists and turns lead it to a climax in which Rapture’s founder, Andrew Ryan, looks up from his office putting green and asks “Stop, would you kindly?” as the player avatar is walking towards him. Control is wrested from the player and the avatar stops. “Sit, would you kindly?” Ryan asks, and the avatar sits. “Stand, would you kindly?”, and the avatar stands. Ryan proceeds to walk up the player and state his designated mantra: “A man chooses, a slave obeys”. And then, Ryan hands the player avatar his golf club, utters the single word “Kill”, and, looking into the camera all the time, repeats “A man chooses, a slave obeys” as he is beaten to death by the player’s avatar (Bioshock). The player is helpless to intervene. “Would you kindly” is revealed to be a hypnotically implanted as a trigger phrase that compels the character to act without question. They have lost all control over their avatar’s actions. The instructions they thought they had been willingly following throughout the course of the game had turned out to be controlling them. Through the extended cognition that the game works so hard to imply, they’ve lost control over themselves.

Shortly after, the player regains control just as quickly as it was taken away. Again, as if no revelation had taken place, Atlas asks the player “Would you kindly” hand control of the city’s security systems over to him, and the game’s quest marker dings with the next notification as though everything is normal. The player has been broken; they have been betrayed and shown their own weakness, their total lack of control in this world. The effect this has on the player is well described in Bioshock and Philosophy:

Gadamer said that there are always risks in any case of a fusion of horizons. One of these risks is having a completely unforeseen experience, or the risk of being changed yourself by the horizon of the “other”— whether the other is a person, a book, a work of art, or a video game. Is this not precisely what happens at the twist of Bioshock? The player plods through the game with a certain hermeneutic horizon that the game maintains up until the twist. Then, it pulls the rug out from under that horizon. The game invalidates it. When successful, Bioshock’s twist sends players reeling. They are left holding fragments of their naive horizon, and broken concepts of what kind of game Bioshock was expected to be. (Cuddy)

The player is once again left holding the pieces and asking themselves “why?”. Why proceed with the horrific actions necessary to complete Bioshock? Why persist through this horrible world and unquestioningly kill and plunder for a faceless voice? Why continue after the moment when it has been so obvious that you are the “slave”, and not the “man”?

So how do they do it? Ambiguous player-avatar relationships, player culpability, and ludoethical tension are perhaps the most complex of the extended fiction techniques discussed in this paper. The game’s first and foremost rely heavily on their tone; tonal consistency with the critique that the game wants to make of the player is an absolute necessity. This includes not just the narrative and atmosphere of the game, but the gameplay as well; games that wish to make the player culpable in horrific acts must force them to participate in truly despicable actions and participate in them in a core sense. The player must be characterized by the gameplay actions they take. Richard Pearsy writes of this regarding Spec Ops;

“Lastly, we decided to tie characterization directly to core game mechanics. Character is action, and this is doubly true in The Line, where for the most part, players use a single set of mechanics during both combat and narrative events. This features most prominently in the game's "decision scenes”. (Pearsy)

Finally, the games must confront the player, implicitly forcing them to reconcile with the actions they took. But importantly, the game shouldn’t confront the player in a necessarily judgmental way; much more effective is the presentation of the events in their true context, leaving the player to judge themselves. Ludoethical tension and player culpability cannot be forced onto a player, the must be implied and experienced naturally.

These games that ask questions of the player, that confront them and demand them to look inwards and discover their own intentions to address their resolution to ludoethical tension, achieve perhaps the most successful form of metanarrative, because it is an entirely unique metanarrative. Why the player chooses to play, why they choose to continue, these are all questions each player can only answer for themselves. The player’s interpretation of what the game is asking them and what their own answers are can and do vary wildly. The game has taken a personal interest in them; it has asked what they think. It has prompted them not to look deeper into the game, but into themselves.

Video games contain one vital element that separates them from all other forms of art; they are directly interactive. Interactivity is defined as “... (of two people or things) influencing each other” (Oxford). Players are required to influence the game and successful video games influence the player in return, but it is typically influencing them to an entertained state. Games try to create feelings of excitement in the player, or feelings based on the narrative events that happen on the screen. Metanarrative video games pursue a different kind of emotional invocation—they pursue the idea of making the player feel things about themselves, making the player understand the medium of video games on a more philosophical level. They push to make the player as much a part of the interactive experience as they can, extending the fiction of the game to include more than just the events that take place on the screen. They bring the player in, disregarding the barriers between the physical and digital worlds. They seek to humble, to encourage, to promote feelings of importance and feelings of control, or to destroy any sense of these that the player might have. Video games that contain and utilize extended fiction build an uncommon and deep relationship with the player and the world around them to make the interaction between them mean more than a simple position of outside control. These kinds of games are not satisfied with being interacted with and displaying the results of those interactions on a screen; they demand to affect the player, just as much as the player affects them.

9 This is not meant to imply that Metal Gear Solid does not have a culpable player, as the actions of the player character are usually no more horrific than that of any spy movie action hero.

10 White phosphorus is a material made from a common allotrope of the chemical element phosphorus that is used in smoke, tracer illumination, and incendiary munitions. As an incendiary weapon, white phosphorus is pyrophoric (self-igniting), burns fiercely and can ignite cloth, skin, fuel, ammunition, and other combustibles. (“White Phosphorus Munitions.”) tips. The insanity and eerie tone of the game permeates through every aspect of it, with player characters becoming more battered and bloodied as the game progresses.

Onyett, Charles. “Hotline Miami Review.” IGN Boards, IGN, 27 Oct. 2012, www.ign.com/articles/2012/10/27/hotline-miami-review.

“ Hotline Miami.” Devolver Digital, 2012.

Yager. “Spec Ops: the Line.” 2K Games, 2012.

Pearsy, Richard. “No Good Deed - Narrative Design in Spec Ops: The Line.” Gamasutra Article, 2012,

www.gamasutra.com/view/feature/176598/no_good_deed__narrative_design_in_.p hp?page=1.

“Bioshock.” 2K Games, 2007.

Cuddy, Luke, and Collin Pointon. “Bioshock's Metanarrative.” BioShock and Philosophy: Irrational Game, Rational Book, John Wiley and Sons, Inc., 2015, pp. 3–14.

“Interactivity | Definition of Interactivity in English by Oxford Dictionaries.” Oxford Dictionaries | English, Oxford Dictionaries, en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/interactivity.

“White Phosphorus Munitions.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 15 Apr. 2019, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/White_phosphorus_munitions.

Read more about:

BlogsYou May Also Like