Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

The 6th installment of a 6-part series. Composer Winifred Phillips shares content from her GDC 2021 lecture, "From Spyder to Sackboy: A Big Adventure in Interactive Music." This discusses methods for hybridizing linear and dynamic music techniques.

By Winifred Phillips | Contact | Follow

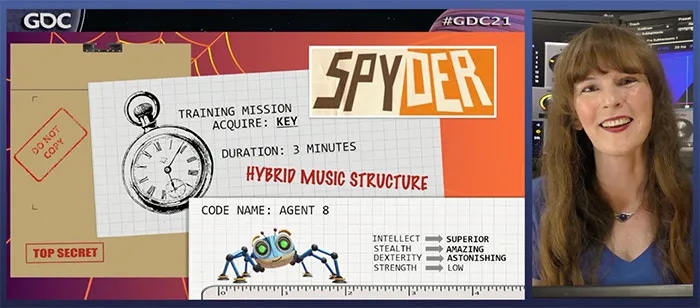

Glad you're here! I'm video game composer Winifred Phillips, and I'd like to welcome you to the sixth and final installment in my article series based on my GDC lecture - From Spyder to Sackboy: A Big Adventure in Interactive Music! Last year I had the privilege of working with Sumo Sheffield on music composition for two projects in simultaneous development - Sackboy: A Big Adventure for PS5/PS4, and Spyder for Apple Arcade. (Above you'll see a photo from one of the sections of my GDC lecture in which I'm discussing the Spyder project). Both the Sackboy and Spyder projects incorporated highly interactive music into their design. While both projects included the basic dynamic models of horizontal and vertical structure, they each brought new twists and quirks to these ever-popular music implementation methods. Since I spent a lot of time bouncing back and forth between the two projects, I got a chance to see how malleable interactive music systems can be when employed creatively. Now, I'm glad to share my best experiences and observations creating music for these two awesome projects!

If you haven't had a chance to read the previous installments of this series, you can start with our discussion of the relationship between a horizontal resequencing approach and the inherent segmentation of traditional song structure. After that, we took a look at the importance of dynamic transitions from segment to segment in a horizontal system. In our third article we explored the possibilities afforded by pure vertical layers. Then we used our fourth article to begin examining how horizontal and vertical techniques can be combined into hybrid forms. Our fifth article broadened this discussion further by placing dynamic techniques into a matrix that includes both diegetic and nondiegetic musical content.

Incorporating both environmental diegetic music and dramatic underscore can be very effective in elevating dramatic intensity during gameplay. By combining music existing in the fictional environment with dramatic underscore, the dynamic music system of the Spyder video game had the ability to fluidly regulate the emotional intensity of events while still supporting the narrative during gameplay. But the Spyder game took this idea even further, so let's move on to a discussion of this final dynamic technique in our six-part series.

By employing one of the more unusual applications of dynamic implementation for its timed MicroMission challenges, the Spyder video game was able to integrate both linear and dynamic music techniques in interesting ways. Let’s discuss how that system worked.

We all know that purely linear music has some distinct advantages. Linear music has a set beginning, middle, and end, whereas nonlinear music is fluid and unpredictable. In my book, A Composer's Guide to Game Music, I discussed the fundamental differences between linear and nonlinear music in games by comparing these elements to the same concepts in game design:

"Linear and nonlinear mechanics are part of a game’s core design philosophy and are therefore most important to the members of the design team, who write the game’s storyline and devise its missions and objectives. As game composers, we may imagine that these design-driven concepts will not have a direct bearing on our work. Yet, we know how powerful music can be in the communication of story, lending emotional weight to concepts and characters and helping in the attainment of immersion. Perhaps because of the intrinsic partnership between story and music, the concepts of linear and nonlinear construction have filtered into the realm of music composition for games. Though the terms do not carry the exact same meaning when applied to our discipline, there are many parallels between linear and nonlinear mechanics in design and in music composition.

"Nonlinear music has the capability to change based on the state of the game and the choices of the player, creating variations that are determined by the player’s actions. Just as a nonlinear gameplay mechanic adjusts itself to the choices of the player, a nonlinear musical composition adjusts itself to the state of gameplay. In contrast, linear music in games consists of compositions that exist in a fixed form within the medium of time—that is, the works are composed with a set musical structure that does not change as the music plays and as time passes. Like a linear game narrative that unfolds with a preordained sequence of events, a linear piece of game music plays with a planned compositional structure that does not alter." (Chapter 10, pages 157-158)

Linear music can more fully explore its ideas without needing to worry about how the maze of a dynamic system might impact an instrumental arrangement, juggle the progression of musical content, or truncate melodic lines. These issues are solvable, but linear music certainly provides a comprehensive list of advantages, affording the video game composer with an added breadth of creative freedom. So, is it possible to preserve the advantages of linear structure while employing dynamic implementation in our tracks?

Let's see how the Spyder game tackled that challenge!

When Agent 8 isn’t saving the world, he’s back at headquarters, where he’s evaluated by expert scientists, and completes difficult training missions to hone his skills. These missions are timed sequences: they last exactly three minutes. Because of this, when composing music for these timed training missions, I was able to work in a hybrid music structure that combines both linear and dynamic elements.

I composed a piece of linear music lasting 3 minutes, with a definitive beginning, middle, and end. Then I added vertical layers to this linear composition. By adding musical layers on top of the mix, this linear system could scale the intensity of the music as the countdown sequence progressed. Let’s take a look at that. Notice how this hybrid linear-dynamic music system makes great use of layers in order to signal when mission objectives are met:

So now we’ve discussed four distinct forms of dynamic music implementation. We’ve reviewed the structural mechanics of the most famous techniques: horizontal resequencing and vertical layering. And we’ve looked at how these techniques can be merged into hybrid forms. We’ve also examined some of the goals of dynamic implementation.

By working with Sumo Digital on both Sackboy: A Big Adventure and Spyder at the same time, I had the chance to see how versatile game music can be, and I developed the greatest appreciation for the complexity and utility of dynamic implementation. As we discussed earlier, interactive music design is highly contextual. The circumstances dictate our choices. There is no best way, or right way. By keeping an open mind and exploring our options, we can discover lots of divergent possibilities. It’s one of the more inspiring aspects of our work as game composers.

Thanks everyone for reading this six-part series of articles based on my presentation at the Game Developers Conference!

Winifred Phillips is a BAFTA-nominated video game composer whose most recent project is the music for one of the latest blockbuster releases in the Lineage series (one of the highest-grossing video game franchises of all time). Recent projects include the hit PlayStation 5 launch title Sackboy: A Big Adventure (soundtrack album now available). Phillips’ popular and award-winning Assassin’s Creed Liberation score was recently singled out by GameSpot as their favorite in the franchise, naming it one of the "best video game soundtracks you can stream." As an accomplished video game composer, Phillips is best known for composing music for games in five of the most famous and popular franchises in gaming: God of War, Total War, The Sims, Assassin’s Creed, and Sackboy / LittleBigPlanet Phillips has received numerous awards, including an Interactive Achievement Award / D.I.C.E. Award from the Academy of Interactive Arts and Sciences, six Game Audio Network Guild Awards (including Music of the Year), and three Hollywood Music in Media Awards. She is the author of the award-winning bestseller A COMPOSER’S GUIDE TO GAME MUSIC, published by the MIT Press. As one of the foremost authorities on music for interactive entertainment, Winifred Phillips has given lectures at the Library of Congress in Washington DC, the Society of Composers and Lyricists, the Game Developers Conference, the Audio Engineering Society, and many more. Phillips’ enthusiastic fans showered her with questions during a Reddit Ask-Me-Anything session that went viral, hit the Reddit front page, received 14.9 thousand upvotes, and became one of the most popular gaming AMAs ever hosted on Reddit. An interview with her is now featured as a part of the Routledge text, Women's Music for the Screen: Diverse Narratives in Sound, which collects the viewpoints of the most esteemed female composers in film, television, and games. Follow her on Twitter @winphillips.

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like