Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

In his latest Persuasive Games column, social game designer and author Ian Bogost builds upon <a href="http://www.gamasutra.com/view/feature/1417/persuasive_games_why_we.php">his much-discussed recent column</a> on 'boring games' by defending video games that make you think or 'zone out' and carry a social or political message, rather than act as pure entertainment.

Every week at my company Persuasive Games we get repeated calls and emails from people interested in playing Stone City, the Cold Stone Creamery training game we created back in 2005. In the game, the player services customers at the popular mix-your-own flavor ice cream franchise by assembling the proper concoctions while allocating generally profitable portion sizes.

The vast majority of people who contact us are not human resources managers or training executives looking to build their own training games. They are ordinary people, often young people, who just want to play or buy the game.

You’d never expect such interest if you read Justin Peters’ recent Slate article about educational games. As Peters charges, “Animating mindless, boring repetition doesn't make the repetition any less mindless or boring. No sane Cold Stone employee will be fooled into thinking that Stone City is anything other than a soul-crushing training exercise.”

Why, then, would so many people be so interested in the game? Perhaps some are misconceived teenagers yet to have been disillusioned by a soul-crushing job. Perhaps others are as smart and skeptical as Peters suspects they might be, and they want to see how possible workplaces represent their expectations for labor. But my sense is that most of them just like ice cream, are intrigued by the Cold Stone work experience, and want to have a go at it for a few minutes.

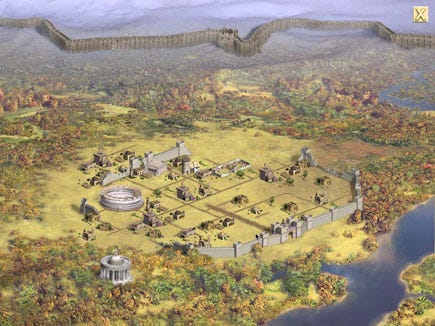

Where is the disconnect? For one part, Peters’ expectations are very high. As he explains in the article, Peters’ ideal model for educational games is Civilization, Sid Meier’s classic game about building a society based on scarcity of resources. There is no doubt that Civ is a great game, one that any designer could learn from no matter their expressive goals. And Peters is right that there is considerable educational potential in this kind of game; Kurt Squire, a well-regarded education scholar, even made it the topic of his doctoral dissertation.

For another part, Civilization is just one kind of game. It is a kind of game that demands significant commitment and devotion. It is a gamer’s kind of game. Are the would-be players of Stone City just too stupid or inexperienced to know about the much more complex and sophisticated kinds of games that they could get their hands on instead? I don’t think so. I bet many of them play Civ as well. I think they are looking for a different kind of experience, one that might not have as much to do with video games as it does with ice cream shops.

In one of my previous columns (“Why We Need More Boring Games”), I imagined a continuum of video game expression, running from Casablanca on one end to the airline safety video on the other. I used this example to illustrate the wide range of topics that have been produced with moving images. I suggested that there are many spaces between those two extremes left unexplored in video games, especially around mundane experiences.

In reactions to that article, many readers assumed I was calling for more traditional games about boring topics. That is one possible conclusion. But another—the more important one—is that games should strive to serve more mundane purposes. The more things games can do, I reasoned, the more the general public will become accepting of, and interested in the medium in general.

One such purpose is education, a domain that has become connected almost exclusively to serious games. This is unfortunate because serious games proponents have also isolated their domain from commercial games, lording their “seriousness” over commercial games implied frivolity. Players and developers of commercial games have taken offense, noting that many ancient board games or modern commercial video games are serious in exactly the way the serious games community intends. This gripe is justified: declaring serious games a separate domain undermines and misinterprets the power of commercial games like Civilization.

But more often then not, the solution the game industry or game press suggests amounts to a similar isolationism. Consider Iron Forge CEO Matt Mihaly’s response to Peters’ Slate column:

I’m just going to refer to [games with a purpose other than entertainment] as Alternative Purpose Games (APGs) until I grow tired of having to explain what I mean every time I use the term. I think APG sums them up much more clearly than ‘Serious’ does when trying to distinguish between games whose purpose is entertainment and games whose purpose is something else.

Mihaly accommodates games with different possible purposes, but he can’t find a way to describe those purposes save “entertainment” and “other.” Just as the serious games community risks isolating and trivializing commercial games, so statements like this do the opposite.

Both of these strong positions on one or the other side of seriousness fail to admit that games might have different goals, forms, and styles based on the contexts of their conception and reception. When Peters or Mihaly complain about games like the ones I make, I treat part of their reaction as critique; I’m not so proud or foolish to claim that I have nothing to learn. But more and more, I hear less useful feedback and more wide-ranging reaction to the idea that games unlike Civ or World of WarCraft just don’t count as games at all.

Ironically, some of the games Peters and Mihaly lament bear striking resemblance to some very popular games of yesterday and today. After all, what makes Stone City so different from, say, Pressure Cooker or Tapper or Diner Dash? Are such games educational? Probably not. But they do simulate experiences that intrigue people.

Why should the restaurant service business be any less fascinating than world domination? Certainly most of us are far more likely to patronize, work at, or open a restaurant than we are to lead an entire society by godlike fiat.

Yet my critics allege that such games simply fail to function as games. Their accusations place the burden of proof on creators like me to prove that they are even worthy of the appellation. Show us, they charge, how this or that game conforms to our idea of what a game is and what a game does. It is not enough to demonstrate that people are in fact playing these games, or discussing them.

No, they must be judged as “good” or “bad” (and always one or the other) in the court of game fandom, or the game press, or the game trades. A MetaCritic rating might be best, but other quantitative measures are satisfactory. For example, Mihaly makes the absurd suggestion that the Alexa rank of my studio’s website somehow bears witness to the cultural relevance of its output.

There is a collective mental block in the games community if it can’t abide any alternative to fun other than boredom, an alternative to infatuation other than suckiness. Is this a culture worth defending?

What if, instead of trying to reconcile all video games with one monolithic set of laws for design and reception, we admitted that video games have many possible goals and purposes, which couple with many possible aesthetics and designs to create many possible player experiences, none of which bears any necessary relationship to the commercial video game industry as we currently know it.

Consider casual games. Casual games already create experiences very different from so-called core games. The casual games industry likes to claim the older, more female demographic of casual game players as its main innovation, but the experience of playing Zuma or Bejeweled is also quite different from that of Gears of War or Civilization. Are casual game players having fun? Maybe.

But more likely they are zoning out. PopCap even built “zen” mode into some of their games after players reported that time limits and other traditional challenges created an experience quite different from the one they were seeking in such games.

Likewise, consider the newsgames I have been publishing recently in the New York Times and elsewhere. These are short web games, and so one might be tempted to call them casual games. But they are meant to produce neither relaxation nor distraction. Rather, they are intended to express an opinion, to editorialize. This is the principal aesthetic I have in mind when designing these games. They might also be satirical or wry or even (gasp) fun, or they might be none of those things. No matter, such aesthetics are secondary to the primary goal of editorial.

There is a maxim I hear frequently in the serious games circles, most recently repeated by Tim Holt in a discussion of the Slate article on Raph Koster’s website. Says Holt:

If you have to make a mistake in the fun versus educational balance, it’s better to be a bit too fun and a bit less educational than the other way around.

It’s a sentiment that seems hard to argue with, if you assume the goal of games is simply education, or fun, or both. If we rephrase this value statement by replacing “educational” with “editorial,” in the case of newsgames for example, it becomes far less persuasive. Education, fun, or other possible experiences might season an editorial game, but who would deny that the latter is its primary goal?

Holt’s example shows that even in the world of serious games, we still have very particular idea about what a game experience should feel like, what form its gameplay should take, and where and in what context games should be played. This is what Justin Peters means too when he lays down the following accusation in his Slate gaming column:

In taking the fun out of video games, companies like Persuasive [Games] make them less alluring to people who love games and more alluring to people who don’t.

I love video games and I love the games industry, so I used to worry about this a lot. I wanted my games to find a home in the traditional commercial sector. I wanted to delight or impress my big league colleagues. I even thought that maybe one day my style of game would justify a place on the shelf next to their games. And maybe some day it will.

I still have nothing but respect for my more traditional industry colleagues, but I’ve stopped worrying about impressing the games industry and its pundits. Or at least, I’ve stopped worrying about impressing them first.

Instead, I’ve started focusing more on the people who might be interested in different kinds of game experiences. People who fly for business more than three times a month, or people who read all of the Sunday newspaper, or people who have kids with food allergies, for example. I am sure these people read magazines and watch television and listen to the radio. But it would be short-sighted to label them ziners or tubers or airwavers. They are just people, with interests, who sometimes consume different kinds of media.

I have started to take rejoinders like Peters’ as compliments instead of criticisms. Gamers are predisposed toward a single response to video games. Those people who don’t love games, to use Peters’ words, simply don’t love the games that gamers love, or they don’t love games in the same way.

I wouldn’t say that I love magazines, but I do buy and read some. If video game playership is indeed broadening, then video games will no longer fall under the sole purview of the video games industry. There will no longer be a single court in which the legitimacy of games will be tried. There will no longer be three great video game gods to whom all creators and players will pay homage.

Instead, there will be many smaller groups, communities, and individuals with a wide variety of interests, some of them occasionally intersecting with particular video game titles.

Some might argue that as video games broaden in appeal, the demands of players will only increase. Casual games or educational games or newsgames will have to become more and more gamey, more like commercial video games of the current variety to meet the increasingly sophisticated demands of these new players as more and more of them become gamers.

But as video games broaden in appeal, being a “gamer” will actually become less common. The demands of players will surely increase and deepen, but those demands may bear little resemblance to the ones gamers place on games today. Just think of the casual gamers asking for zen instead of challenge. In the games industry of tomorrow, the gamers will be the anomaly. Instead we’ll just find people, ordinary people of all sorts. And sometimes those people will play video games.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like