Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

This article talks about the difficulty level of Puzzledorf, how it changes over time, and how I tried to use that both to engage and retain players to help them finish the game.

This article was originally posted here on my blog.

Introduction

The difficulty level of video games is a big topic, often with strong view points on varying ends of the scale.

“Hard games are more rewarding.”

“Games should be easier and more accessible.”

And many other points of view. What I am going to discuss in this article, however, is not so much how hard the game is overall, but rather, the difficulty pacing – how quickly the game progresses from it’s easier, simpler challenges and into the more difficult challenges.

I will be reflecting on the difficulty pacing in my own Steam release, Puzzledorf. Keep in mind, appropriate difficulty pacing is going to vary based upon many factors, including genre and target audience. I think I cover enough general principles to be useful as a guideline with any game.

3 Types of Curves

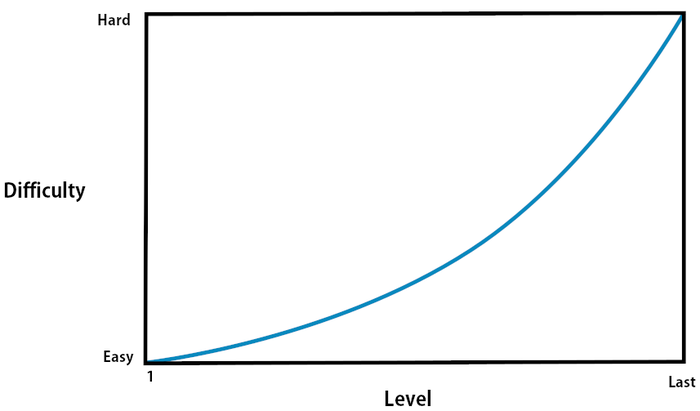

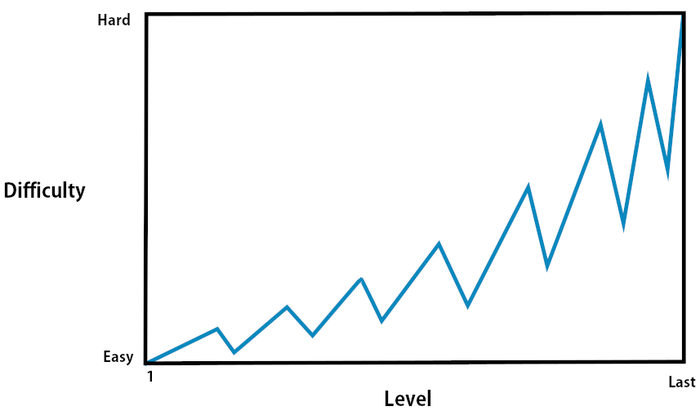

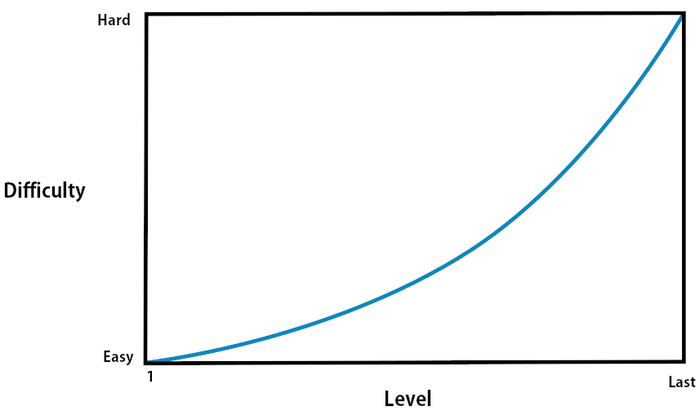

When I sat down to create Puzzledorf, I thought the first level should be the easiest, the last level the hardest, and that the difficulty would gradually increase throughout the game at a fairly constant rate. This is roughly the same approach I have taken with other puzzle games. A graph demonstrates what I mean.

Gradual Increase

The above graph demonstrates (not to exact scale) roughly what I tried to accomplish. A gradually increasing difficulty, easier in the first half to slowly onboard players of all skill levels, then ramping up difficulty in the last half of the game.

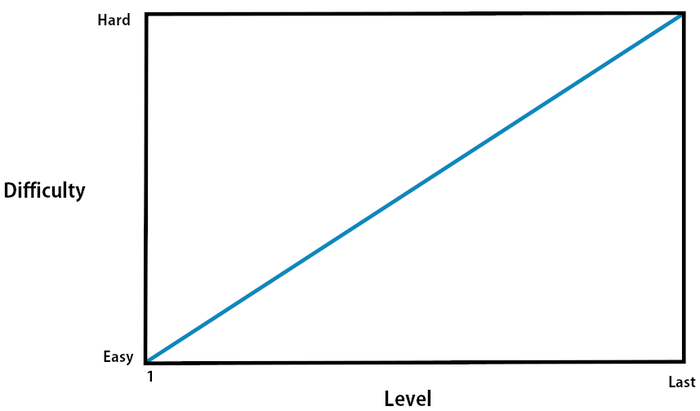

Below is another way some games may approach difficulty pacing.

Constant Increase

I think it’s fairly self explanatory – the game increases in difficulty at a constant pace form beginning to end. Of course try as one might to create a constant difficulty increase, one player may get absolutely stuck on a level, and another player blitz through it. There are always anomalies you can’t account for.

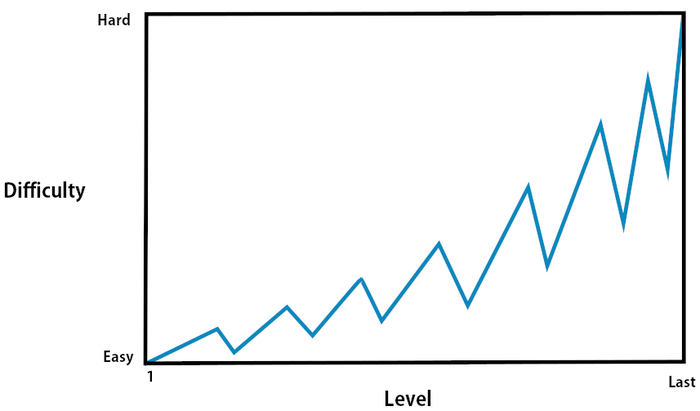

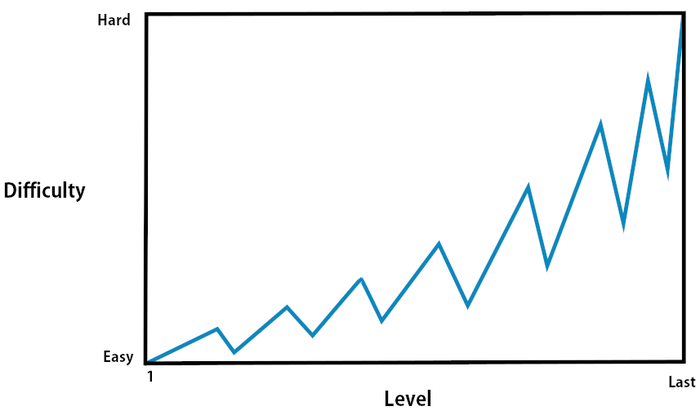

Below is the difficulty curve I ended up using, after much play testing and a discussion with a friend.

Variable Increase

Rather than either a gradual or constant increase, I used a variable difficulty curve, modelled off of the gradual curve. Psychologically it had a healthier impact on players experiences, causing players to have more fun, feel empowered and they were more likely to finish the game. I will discuss all the curves and my experiences with each approach further below.

Reflecting on Constant / Gradual Curves

Of the 2 initial types of curves, constant and gradual, I think the gradual is the better curve. Having that gradual difficulty in the beginning allows players to ease in to the game, learn the rules and develop their skills before they get to the harder challenges at the end. However, that last part, where the difficulty ramps up, can be problematic for some players. Constant difficulty curves have the same issues.

Through play testing, here are some issues I found with both curves as the game gets harder:

They can be discouraging

They can be exhausting and overwhelming

Let’s talk about that in a bit more detail.

Potentially Discouraging

This one surprised me and was a big factor, particularly with puzzle games. Some people are just scared of puzzles, afraid they might not be “smart” enough to do them. Putting aside the fact that I think everyone is smart enough, and a good puzzle game should equip you with the skills to beat it, this mentality becomes a problem as the difficulty gets harder. Please note, the level times and numbers below are hypothetical scenarios for the example.

If level 11 takes a player 15 minutes, and level 12 takes them 30 minutes, some players, rather than seeing that the game is getting harder, instead feel like they were slower and not good enough. I got this as verbal feedback from quite a few players. This really surprised me, and I think it’s rooted in the fear of players wondering if they are “smart enough” to beat the game. It was at this point some players would stop playing altogether, feeling like they were incapable of beating the game.

This was unfortunate as I want my game to empower people to feel a success because they beat it, and to equip them with the skills they need along the way.

Exhausting and Overwhelming

Some players, experiencing that each level successively took longer, would then assume (correctly) that the next level will probably take them as long or longer, and then give up. Knowing it was going to get harder every time was too overwhelming. This is particularly noticeable in a puzzle game, because you might be spending periods of time just looking at the screen and thinking. In a busier game you are potentially less aware of the fact.

In the scenario of a constant or gradual difficulty increase, because every level is harder and takes longer, the player rarely feels like they are improving. It’s purely psychological – they are improving, but they don’t feel like it. For some players, this demotivates them, and they stop playing. This is where the variable curve excels.

Benefits of Variable Curve

From my play testing experience with Puzzledorf, I found several key benefits from the variable curve:

Breathing space and pacing

Encouragement and empowerment

Reinforcement of learning

Due to a combination of all of the above, I noticed players were overall more likely to finish the game, but back to that in a minute.

Breathing Space and Pacing

One of my favourite games is The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time. There are big, exciting dungeons that you have to complete, and generally they get harder with time, but between the dungeons you can explore, walk around towns, ride your horse across the fields and look for secrets – it’s all the stuff that happens around the dungeons that made me fall in love with Zelda. And the moments outside the dungeons allow me to rest; they create space with quiet moments between the excitement.

It’s these quiet moments in a lot of adventure games that create the pacing, and make the exciting bits more rewarding. This kind of pacing also helps prevent the player getting overwhelmed and exhausted. It’s harder to achieve in a puzzle game, but not impossible. You can achieve it, to some degree, by varying the difficulty.

Knowing and believing that the next puzzle will always be harder can create tension. Experiencing variable difficulty in the puzzles, finding out you finished a puzzle quicker than the last one, makes a player feel rewarded and more relaxed. They feel like they are improving, which lessens the tension and creates a healthier pace to the game.

Encouragement / Empowerment

As I talked about in my previous article, Tutorial Design in Puzzledorf, I like to use experiences, rather than text, to teach the player. To solve the puzzles, you have to learn various techniques. Some are basic: if you push a block into a corner, you can’t push it out. Others are more advanced. I don’t tell the player they’re learning it – they just learn without thinking as they play. And by gradually introducing the players to more complex techniques, and using the layout of the levels, I slowly teach through design.

It’s important to note that players are learning most of this automatically without thinking about it because it’s just part of the puzzle. This is partly why, I believe, when I used a more constant difficulty curve, since each puzzle took longer to complete, players felt like it was because they were too slow to solve the puzzle, not realising that it’s simply because the puzzles are harder and require more advanced techniques. They don’t realise how much they have actually learned.

This leads back to the interesting conversation I had with a friend. This guy loves super heroes and games with super heroes. He made an interesting comment when we were talking about my game.

“You know, something that’s really cool about when you get a new power in a game, is when there’s a couple of easier levels to let you enjoy the new power, to use everything you just learned, and feel like you’re awesome. Then you feel like you’re actually getting better at the game, before bringing out the next ability, and the game gets harder again. It lets you really enjoy it. Maybe you could use that in your puzzle game somehow.”

That was the seed of inspiration for my variable difficulty curve. By throwing in an easier level or two, after a really tough challenge, the player gets to use the skills they learned to smash out a level and feel smart. This sense of accomplishment helps them to feel they’re improving, which they always were; you’re just helping them to know it.

That feeling and that knowledge empowers them. That, in turn, motivates and encourages them to try and finish the game. And it’s that feeling of accomplishment that leads to the pacing, because that high emotion of success reduces the tension, and the variability in the tension creates the pacing.

Reinforcement of Learning

This is where I was talking about teaching through experiences. Throwing in some easier levels that let the player use skills they’ve just learned is a good way to reinforce their learning.

In classic Zelda games, you would obtain various items that all possessed unique abilities. Then the dungeons would often be full of puzzles and challenges that only that item, with it’s unique abilities, can solve. They start simple, then gradually get more complex. Nintendo very cleverly uses an entire dungeon to vary this idea of gaining something, learning how to use it, then becoming an expert with it. Then often later dungeons and the larger world will offer opportunities for the player to indulge those skills further.

Finding ways to employ this model of learning, throughout a variable difficulty curve, is useful for teaching through design, as well as a fun way to learn and play.

Results

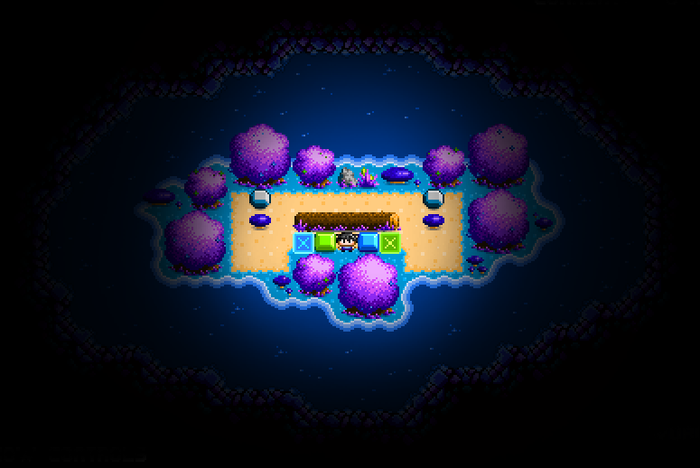

When I originally had a more constant difficulty curve, as pictured below, I noticed fewer people were willing to finish the game. Some people, after a few difficult levels, just gave up. After probing a little, this is where I realised that some of the players were getting overwhelmed.

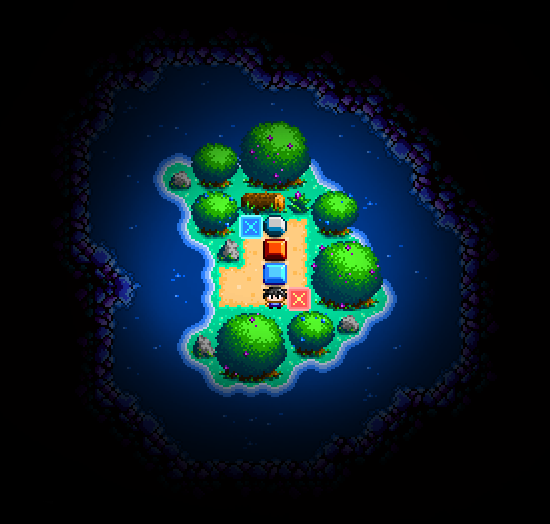

By varying the difficulty, as pictured below, people were more likely to play further and finish the game. Instead of giving up after a tough level, I noticed that a lot of people couldn’t help themselves and started playing the next level. People seemed happier overall while playing, looking more refreshed and determined as it got tougher.

Conclusions

Varying the difficulty, and not just increasing it over time, appears to empower players, giving them a chance to feel more relaxed and enjoy the game more, and more likely to finish the game. Using a gradual difficulty curve as a base, but then adding in variability, creates better pacing by varying the tension.

While this article was particularly focused on a puzzle game, I think much of what I learned is applicable to other genres, something I intend to explore as I develop other types of games in the future.

If you want to learn more about Puzzledorf, you can see the website or check out my blog.

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like