Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

In this analysis, MMO man Simon Ludgate takes a look at how different developers have both erected and destroyed barriers to players actually playing together in the MMORPG genre -- breaking them down into two different types, and suggesting a path forward to building strong player bases.

What makes MMOs special? Other players. Lots of other players. Whole communities of other players. While I may semi-seriously joke about other players being the biggest problem in MMOs, they're also the genre's greatest asset -- some might say even say their only redeeming feature. Why pay a monthly fee to play the same game, experience the same content, over and over, week after week? Because you're doing it with other real people.

I've long held that the most important feature in any MMO is to build a strong player community. It doesn't matter how shiny or content-filled your game is: if it lacks in community, players will leave. Community makes or breaks an MMO: games that have leapt off the starting block full of praise and high review scores fell flat on their faces when they failed to build strong player communities, and games so bland they ought never have been made in the first place are still running today thanks to player involvement.

More and more companies are recognizing the importance of community management. They hire community managers to lurk on official forums all day and interact with players; they build in-game systems to help players interact more easily and more meaningfully; they design content that drives players together rather than apart.

But not every company is on board with the new way of doing things, and time and time again I see games fall apart because "marketing" or "balance" decisions have driven players apart.

One such bombshell was lobbed out of Square Enix's office last Thursday (Feb 9, 2012). Final Fantasy XIV, its MMORPG sequel to the successful Final Fantasy XI, has struggled since launch with poor design choices and lack of content that upset many players. Nevertheless, the game kept running on indefinite free trial and retained a strong community of hopefuls (about 12,000 simultaneous logins just before subscriptions started in December of last year).

Based on this, Square Enix appointed a new producer, and swore it would turn things around. Then it started charging a monthly fee, despite the fact that the announced re-launch was more than a year away. Granted, that turned away the less dedicated fans, but it didn't completely tear the community apart, as the Final Fantasy faithful paid up and kept playing, hoping their unsubscribed friends would one day return.

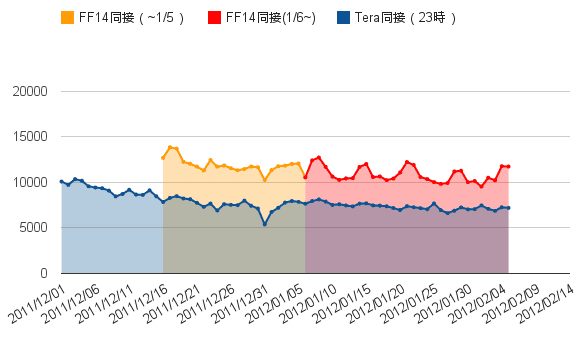

(Caveat: This graph of player population numbers is based on player-generated estimates. Orange is pre-subs, red is post-subs. However, unless Square Enix wants to provide data showing the contrary, I assume these numbers are pretty accurate.)

In other words, despite the problems with the game, the strong game community kept things going, and Square Enix's response has largely been "We'll get it working for you; stick with us until then."

This makes the company's most recent announcement all the more confusing. Square Enix announced server mergers for FFXIV, but not the normal "two into one" procedure most gamers are familiar with. Instead, its original plan called for the elimination of all the previous servers, forcing all players pick one of 10 new servers to move to. Well, not all players. Only active subscribers get to pick where they go. The rest will be relocated randomly.

In other words, Square Enix was looking to completely shake up the remaining population and, in the process, isolate any lapsed players from their prior in-game friends. They were also going to delete every Linkshell (guild) and wipe every friends list (and blacklist) clean.

Current subscribers were being told their non-paying friends are being taken away from them. Current non-subscribers were being told they were barred from sticking with their friends. Both groups are upset, and rightly so, because playing with friends is what makes MMOs so special.

Thankfully, the lead producer for Final Fantasy XIV, Naoki Yoshida, rapidly backtracked on the original announcement. The original official announcement was taken down, though it can still be read in its entirety here. The issue is still ongoing, and will doubtlessly develop further, but the recent event is a prime example of what I want to discuss in this article:

If you're going to get people paying for your massively multiplayer online game, you have to LET them play together.

There are many ways you can prevent your players from playing together. The most obvious and brute-force way is to send them all to different servers and never let them see each other again. But there are other ways to prevent players from playing together, ways that permeate even the games made by the most well-meaning of developers.

Take, for example, Rift, Trion's first MMORPG. Trion has a strong community focus, ranging from the usual "letter from the producer" feedback to more personalized GM interventions to promote in-game camaraderie. Trion also works hard to get people playing with their friends. Its Ascend-a-Friend referral program, in addition to handing out a free trial, also automatically adds referrer and referee to each others' friends lists, making it easier to find each other in-game, and giving them the ability to teleport to one another. But as Isabelle Parsley of MMORPG.com points out, this doesn't actually let them play together, because new players start at level 1 and most referring players are at level 50.

I experienced this when I invited a friend to play Rift. I was level 50, doing 50 stuff, and he was starting out at 1, so I made a new character to accompany him.

And it was going well, but sometimes he'd log in while I was in the middle of 50 stuff, and he'd level up ahead of my alt, so I'd have to level up my alt to get caught back up again, until he got so far ahead of my alt I just waited until he leveled up enough to catch up to another one of my alts, which then kind of teamed up with him again for a bit...

Long story short, he quit before he got to 50, since he never "really" got to play with me.

Rift is also trying another tactic that hasn't worked well in other games: the capped level endless trial. World of Warcraft lost nearly 20 percent of its subscribers despite implementing an endless free trial up to level 20. Warhammer Online saw players cancelling their subscriptions to play in the free trial because that was where all the PVP action was. And Lego Universe had to shut down when it found it was unable to convert free trial users into subscribers.

The problem with level capped free trials? It doesn't let people play together. Oh, sure, it technically allows them to cross paths, and subscribers could technically make low-level alts to play with free trial players. But the reality is that most subscribers are going to be higher level than the free trial level cap and they'll never have any incentive, let alone opportunity, to play with them. Left on their own, free trial players are basically playing a single player game, and then asked if they want to sign up for a subscription to this single player game. It won't work. It can't.

Rift

It is possible to design a game with "letting players play together" in mind. The most important issue is to overcome segregation barriers: the factors that completely prevent players from playing together. There are two kinds of segregation barriers: operational barriers and design barriers. Operational barriers refer to elements of the game that concern the game's operation and are largely unaffected by a player's game experience. A subscription fee is an example of an operational barrier; so is being on different servers.

Eliminating multiple servers (ala EVE Online) or allowing players to freely transfer from one server to another (ala Rift) are good examples of overcoming that barrier. Charging a fee for a server transfer or denying server transfers at all is a bad way of overcoming that barrier. This is because the operating barrier is often perceived by players in opposition to their goals.

Design barriers are trickier: they're elements of the game that separate players. These are often desirable elements in a game, such as levels, because they give players a sense of accomplishment, of going someplace they couldn't before. Getting enough gear to be able to face the bosses in a challenging raid is an example of a design barrier. So is being on the right stage of an epic quest to enter a particular dungeon.

But design barriers are also being challenged by game designers: games that offer players the ability to "mentor" "sidekick" or "level sync" overcomes the barrier presented to players of different levels, for example, and easily obtainable "welfare epics" allow games to distribute enough gear to get players into higher tier raids after lower tier raids have been abandoned.

Don't get me wrong. I'm not exactly in favor of welfare epics. I actually prefer ways to get better geared players back into lower tier instances, such as Rift's weekly raid quests that encourage even the best end-game players to "pug" (pick-up group) the earlier raids, giving less intense players a chance to see that content and get some gear. Again, this points to good ways (motivations) versus bad ways (gear handouts) to solve a design segregation barrier.

But these systems don't always work. Players are locked to only one raid instance a week to prevent them from getting too much loot, but this means they can't go back and help friends complete the instance, even if they were willing to be locked out of getting more loot. Raid lockouts are another design barrier that might need some rethinking if players are to be encouraged to play together. This is especially important if your goal is to get people who aren't interested in a raid's loot into the raid in the first place. Why offer a special incentive to get high-end raiders into low-end raids, then lock them out of the zone after one run?

Likewise, the automatic dungeon finders that group people and teleport them into a dungeon, featured in games like WoW and Rift, were supposed to overcome social barriers to actually forming groups with players. But the effect systems like these have on building communities is questionable, at best.

Sometimes, the differentiation between design and operational barriers blur, such as in Turbine's Dungeons & Dragons Online. When DDO went free-to-play, it locked many of the game's adventure areas as premium pay-only content, an operational barrier.

But Turbine also allowed paying users who had bought the adventure area, or who were paying for a subscription, to buy guest passes, allowing users who did not buy that adventure to accompany that player inside.

This overcame an operational barrier, but it left a design barrier in its place: what motivation was there for a player to hand out guest passes to strangers? What motivation was there to do that dungeon at all, rather than a free one?

Dungeons & Dragons Online

DDO's guest passes are an example of letting players play together, but what about the getting them to play together part? The "let" is a necessary first step; the "get" is the key to customer satisfaction, conversion, retention, and all that monetary goodness. But here are a few bits of advice to get everyone started:

Operational barriers are generally a Bad Thing. No one likes to be shut out from their friends because of some arbitrary operational setting a producer in a dark, dank cell decided on. Reducing operational barriers as much as possible should be a primary focus.

The free-to-play "revolution" sort of embraces this idea, by tearing down the most obvious of operational barriers: the subscription fee. But the subscription fee doesn't have to go, so long as the product you sell provides good value to all its customers -- including those who opt out of subscribing for a period -- and avoids other operational barriers.

Design barriers are generally a Good Thing. They let players feel a sense of accomplishment and are often the main goals players work towards overcoming in games. The problem is when they get in the way of players playing together.

There are two general ways of overcoming these barriers: the leg-up approach of letting players bypass the barriers, which is generally an unpopular approach, especially among those players who worked hard for the satisfaction of overcoming them legitimately; and the bribery approach of paying off players to go back down to that stuff they had done before, which is generally popular and, if well implemented, encourages building those lasting social community bonds that are so integral to building a strong game in the first place.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like