Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

In this in-depth Gamasutra interview, Midway Austin's Harvey Smith (Deus Ex series) focuses on the surprisingly political elements in his new title BlackSite: Area 51, as well as wide-ranging looks at quality of life and the future of the game medium.

Game designer Harvey Smith is perhaps best known for his work on the Deus Ex series for Ion Storm - though he has also worked on titles for developers such as Origin and Multitude. He joined Midway in Austin as studio creative director in 2005, and his first title for the company, BlackSite: Area 51, is a first person shooter that -- on the face of it -- looks similar to many titles on the market today.

But as this extremely candid interview, conducted earlier this year and published in shorter form in Game Developer's September 2007 issue reveals, the inspirations for this Unreal Engine-powered shooter are deeper and more complex than average. Smith focuses on the surprisingly political, Iraq Occupation-derived elements in the game, as well as wide-ranging looks at quality of life and the future of the game medium.

Tell us a little about the background behind the genesis of BlackSite: Area 51.

Harvey Smith: It's been a weird arc with this game, both for me personally and the people looking at it. I moved to Midway to work on this one particular game that we haven't announced yet that's part open-world, part RPG features. And I was like "this is great, this is exactly what I want to work on!" Then in the background -- though I love shooters too -- there was this first-person shooter, and I just wasn't that interested in it. At first, I built the department there. In the first year, I was just hiring and firing. I'd say that I fired more people than anybody, and I hired more people than anybody, and sort of framed up the two games, and it was very dissatisfying. I was effective, I think, but it was very personally dissatisfying, because it wasn't on a team. This game got into trouble about a year ago, or a little before that.

But about a year ago, my boss Denise just said, "Do whatever it takes," and I said, "Okay, I'm going to have to move my desk." And so I moved into the team and I said, "Fuck this Area 51 thing. I don't know what you're talking about. I don't want to do that." And I started saying that we were going to call the game BlackSite. The executives at Midway were like, "What?" So we pushed small town environments, which they thought was odd. Everybody thinks that you've got to be in a giant alien stomach or on a weird ship or something.

Or a vomiting whale.

HS: Yeah exactly, but I've always been about the very grounded. The Deus Ex levels I love the most are the ones that look like a train station, or a bathroom, or a bar. So we pushed that, pushed the name BlackSite, and pushed the subversive political angle, which is I think a lot stronger than what marketing thought it would be.

Right -- part of it is taking place in Iraq. How much are you doing with that element?

HS: Quite a lot, actually. When I first wrote the one-page BlackSite story, it ignored things like, "Sure we want to steal some of the breakables from Stranglehold. We've got vehicles, [and so on]." We eventually did squad command and this interesting squad morale feature, and I think those are cool. But always in the background, I was like, "Look, I'm really fucking angry right now. Everything I read pisses me off." You can do this two ways: you can be super heavy-handed and propagandize -- and I wasn't interested in that -- or you can try to organically weave something through the entire work. If you do that, you run the risk of minimizing it so much that nobody notices it.

I think that we've actually done a pretty good job of not pushing it down your throat, and yet not letting it vanish either. It's very much there. The game starts in Iraq. You're Aaron Pierce, this Delta Force assassin, essentially. Something happens to one of your squadmates in Iraq. You're looking for weapons of mass destruction that aren't there, of course, and then you move into small-town America. At that point, you're U.S. special forces operating on American soil. It's subtle stuff, but moving into the first mission where you're about to be briefed, you're going past people and cars and checkpoints that have been quarantined. They're going, "Hey, you guys can't do this," and somebody else is saying, "The hell we can't."

Then it just gets more and more subversive from there as Pierce figures out that the primary enemy in the game, which is being called an insurgency operating on U.S. soil, is really wounded American soldiers from Iraq who are being disappeared by the government, taken underground, and experimented on with regard to this "Army of One"-type program. So we go into the Walter Reed allusions, and the Abu Ghraib allusions, and we try to do it in such a way that won't make people vomit or whatever, but at the same time, it's definitely there. The whole theme is, "Who is the enemy? Look at the enemy -- do I look like the enemy to you?" One year, somebody's a freedom fighter, the next year they're a terrorist.

Do you think people are going to take some of that away from it? I think that grounding it in a plausible beginning is a good way to get people to think about it.

HS: We said early on that it would be great if parts of the game looked like CNN footage. We're working with Unreal Engine 3, which is very powerful, and we're making a game that is a Half-Life 2 or a Call of Duty 2-style game. We're all huge fans of those -- Half-Life 2 is one of my favorite games of all time. But it's weird; you start doing that sort of thing, and of course you've got the squad morale and all that, but you start doing that sort of thing when you're using Unreal and it changes everything.

The Unreal Engine doesn't like certain things, and it likes other things. But grounding it very much so that it wasn't just a goofy game about aliens or whatever -- it's an allegory, in the same way James Whale put together Frankenstein in the '30s. He was simultaneously talking about a monster for 13-year-olds and a totally disenfranchised character for those who felt disenfranchised. In that same way, if we're successful, we would like to do that sort of thing.

I think it's a good thing. I was just talking to Alex Seropian, who's doing Hail to the Chimp. I was trying to see what kind of political agenda he's got going on there. On his side, it's much more light-hearted.

HS: Ours is kind of dark. We try to lighten it up every now and then -- our mission titles, you know how even if you're not really hitting a gated spot, because most of it actually just streams in, but when you reach something that feels like a new mission or sub-chapter, we fade in things like, "Misunderestimated," or "Mission Accomplished," or "Shock and Awe."

"The Decider."

HS: Exactly! That's one I'm stealing right now. We thought through this long list, like WMD MIA - that's one that's all acronymns. We're going after it, but we're trying not to be obnoxious about it. The game definitely has a tone, and it's the most polished game that I've ever worked on, which is what I'm super excited about.

I'm really happy that someone is at least trying, because we talk as an industry a lot about making people cry and laugh, but above and beyond that, we can try to take some responsibility in certain ways.

HS: With Deus Ex, when we were building missions, we said initially, "Wouldn't it be cool if, in addition to the guy telling you 'Here's some ammo, go kill everyone. These guys are terrorists, remember that -- they're terrorists,' there was another guy who stopped you and said, 'Hey, remember these are people. They believe what they believe, and if you can possibly do this mission without killing anyone, that would be awesome. Here's a taser.' It's kind of ridiculous at some level, but you were able to do that as a player, and you would not believe how much we had to fight our own team. [It was like,] "Dude, that's so lame."

Similarly, we had a conversation the other day about how gamers accept certain features after a period of time, and then they think that's the right way to do it, because it's the least frustrating. But initially there's this giant wall of resistance, and I think there's a little bit of a resistance related to the content. This one game I want to make, I would say that moms would like more than hardcore gamers, and yet it would benefit from something like the Unreal tech, it would be very visceral, it would be very much about moving things physically through a space, and it would involve breakables.

It wouldn't be comedy, but it wouldn't be a soap opera either. Kind of Lara Croft without the guns, or something. I have no idea whether I'll ever get to work on that game or not, but I just mention it, and maybe ten percent of the people tapped into the industry are like, "Whoa, way to go. That's cool," while 90 percent of the people have a giant wall of resistance. BlackSite has endured the same sort of thing.

It's really hard... you've got Nintendo trying to push for this different market, while also saying "but we're still hardcore too, don't forget!" And you've got every other console maker saying, "We're hardcore! But also we've got this [casual-oriented] thing on the side." It depends on where you're going, but you're swimming upstream either way.

HS: Either you're the company who would like people to take you seriously, because you previously made kids' games, or you're the company that is mostly known for Mortal Kombat, and you would like people to take Stranglehold and BlackSite seriously, as a new brand almost. Or you're the company who only makes "tear peoples' heads off games," and you would like to introduce some kids' bowling game or whatever.

Or you're Warren Spector or Alex Seropian and you head off on your own and make your own thing.

HS: Good luck with that too! That's difficult as well. I love Warren. He lives in Austin, and we talk all the time. I really admire what Junction Point is doing in terms of being independent and all. I tried it for eight months.

I didn't know you were independent.

HS: For a while. I left Ion Storm, and I just said, "I'm quitting this cool job that pays a lot where I'm well-respected." And I thought, "Why are you doing that? Who are you going to work with?" and the answer was "I have no idea. I'm going to be unemployed." I consulted for Ubisoft, NCSoft, and EA among others, and had a great time. I wrote design docs by the pool at my condo and things like that and tried to get funding, and in all of the deals I was offered after a while, the publisher had such a chokehold on what was going on. It was like, "Well, I might as well work for one of these publishers."

So I don't know what I'm going to do. At some point I'll probably try it again, actually. Our tech director at our studio at Austin ran Charybdis, his own company, for eight years, and during that time they worked on their own engine, and they did all these military tank simulators. I talk to him all the time because he's the guru that's helped us take Unreal and add Stranglehold breakables and streaming so we could do wider-open areas. Some of our road sections, like with driving, we could only do because we tweaked Unreal a little bit. It was like, "How did you do that for eight years? I never even heard of your company." He's like, "Well, it's all about being ruthless and cutting the right deals with people, and pushing and being hungry." It sounds really good if you can make it work. That was also a different time in the industry. It's very different now.

I think things may be changing. There's an attempt to change.

HS: I agree. Middleware has made a huge difference. What I always tell people is that we made Deus Ex with literally three programmers, so we had two little teams of level designers, and a bunch of artists. It was probably a team of 25 total. But three programmers! That kept all of the feedback loops in everybody's heads. Instead of having to go to talk to your five guys, you only had to talk to one guy. You had a texture artist you'd work with, or whatever. That helps so much. You lose so much as soon as you have to talk to ten people. When you have to talk to 60 people, you lose tremendously.

You have to make sure they're doing what they're supposed to be doing, and you have to tell them.

HS: Constantly! A hundred times! I've literally been working with people, and they look up and say, "We're doing Humvees in the game?" or some strange thing, and I feel like I have to be an asshole sometimes, just to drive things home. I've had guys working with me for years turn to me and say, "Why are small towns cooler? Why aren't we doing flying saucers, and you're in the belly of a vomiting whale?" or whatever. I'm like, "Well, Hitchcock made The Birds, and it's about these freaky birds, but it had phonebooths and diners and playgrounds. Here's why that's evocative to people who grew up around those things." Anything you do in this industry is swimming upstream at some level.

You're still having to sell the same ideas to the same people?

HS: Not so much, because once we get to the point where we were showing the game to random people, you can read what they respond to. This thing that you thought was going to be the shit, turns out nobody cares about it. The thing that you didn't think would be that cool, but you pushed it and pushed it and really made it so that it was a real thing in the game, and you're not just talking anymore, could be something that people respond to and comment over and over about it. Then your team goes, "Aha!"

In the Xbox Live demo, there were aliens everywhere and you could shoot them, but the thing I heard people respond to was when you sent a guy over to open a door and he couldn't open it, so he broke the window and unlocked it from behind. That was the thing everyone responded to; that's just a logical thing that would happen in real life.

HS: It's funny that you would say that, because you never know what those things are going to be. In Deus Ex, we had a meeting with this guy we hated, the same guy who gave us a management lecture saying that if we all dressed properly -- meaning Dockers and khaki pants -- then our troops would respect us. Before he left, though, that guy said, "You know what would be fun in this game? If I could go into the women's restroom and get bitched out for it by some woman." We all just went, "Please leave," and then he left.

Later, we were like, "Hey, that's kind of interactive. What if we put a trigger in the bathroom, and if you happen to wander in there, your boss later says, 'And by the way, JC, stay out of the women's restroom,' at the end of the briefing?" And we did it, and everybody who played Deus Ex commented on it. We couldn't believe it. We were like, "Dude, they didn't even notice our weapon modification system, but they noticed you broke this social taboo."

Similarly, we realized [this] with the Xbox Live demo that the moment it's raining at night and you're in a convenience store and you're looking through the glass. The reborn scout is shaking this van, and right before he kills the guy in the van and rips the door off, the guy inside the van tries to roll up the window. People responded to that. It's these little character building moments that [matter].

I think that's one thing that is missing a lot in terms of story telling in games -- moments and actions. There's no such thing as character beats most of the time.

HS: We literally beat charted out the game. We stole this lesson from Hollywood. We've got 32 missions in the game, and we look at them and think, "What's the position of the sun in this mission? What's the color palette? What did your squadmates just go through emotionally in the mission before?" So much of that is driven by technology, though, right? You spend all this time to get your animation system going, so that when they run up and get shot, they look for cover points within the world, and then they crouch behind them and, oh god, they popped, so we've got to have them more naturally turn. Then, oh god, they can rotate in place without moving. That looks goofy. Let's have them play a little animation where they move their leg or whatever.

You do all that, and the system finally works, and then they're robots. Congratulations. Things like the Delta Force guy breaking the window and reaching around -- it's another example of the subtle stuff we're weaving in, but it's like eminent domain. Delta Force has arrived at your auto mechanic shop or gas station, and they can break the window and get in. You talk to a yokel later who is a tinfoil hat-type guy who runs the place, but at the same time, it was a character-building moment. Like, "Should he blow it up with C4?" No! How about he reaches around and unlocks it?

That's really good stuff. The thing I liked the most about Gears of War was the graphics. People did talk about the story being good, but -- and no offense to the co-writer on this...

HS: She knows that they tried a bunch of stuff. She came in and inherited the story, and then a lot of cuts had to happen to make the date. She learned a tremendous amount. She's very analytical about it.

The fact is, you spend the first three missions trying to put this thing down in a hole so that you can map out all these charts, and it doesn't work. That should be a dramatic moment. But within 15 seconds, this guy is like, "Oh hey, this thing I was carrying the whole time does everything we just tried to do for the last three missions, so it was all pointless."

HS: The game writer's job is never easy, because they have to work with game designers, and the game designers' job is never easy -- the level designer's job is never easy, because he has to work with writers. The two things don't really go together like peanut butter and chocolate, so you have to be very, very careful. I think Gears of War is the best art-directed game ever. All that stuff like the roadie run, I looked at it and said, "Why don't we do more of that?"

The guy who was supposed to direct the Halo movie, Neill Blomkamp -- years before that, we looked at these two videos that he made. One is about this robotic cop in Johannesburg or something, and the other is about racial tension with aliens in some third-world country. Both of those are really amazing. All this amazing camera stuff that feels like a documentary, or like a police surveillance video. There's all of these little tricks. We have camera technology that's more capable at some level than real-world camera technology, because we can fly through buildings and do whatever. Yet very seldom do people mess with that at all.

I feel like we've really regressed in terms of camera use in recent years. We were building up because we had all of these single-player third-person experiences, and then everything changed to become about first-person, or open worlds. We no longer have a forced camera. We were getting to this stage in games like Silent Hill, where you've got these dynamic camera angles that freak you out.

HS: Did you play Fatal Frame?

I haven't, but I've heard a lot of good things about it.

HS: I love Fatal Frame II. Some of it's really cool. I also like games that really understand horror. Whenever we were around the Thief team, we would talk a lot about horror. Not just giant monsters with big teeth, but subtle things. Fatal Frame does that really well.

I feel like since we've gotten to this other stage, we've really regressed.

HS: But that's going to happen over and over. Whereas films started and built up, and every innovation built on the last one, and yet you can still show a film from the earliest days of film in a movie theatre today. [In games] every five years we reset, and you can't play a game from 15 years ago on a current machine, generally. Somebody comes up with open-world tech, or materials with specularity in them. "Ooh, the street looks shiny and wet -- okay, now we have to redo all our textures so they look shiny and wet." And then it becomes, "that's too expensive. Now you can't do this camera thing you wanted to do last round." And I say, "We could do this on the PC in 1993. Why are we not doing this today?" And somebody's like, "Well, because it takes five times longer to make materials-based textures than it does old-school textures."

I was kind of spoiled. I guess my first significant gig in the gaming industry that lit me on fire was when I was lead tester on System Shock. For ten months, I got to work with the System Shock team. Doug Church just blew my mind, and the team blew my mind. They did things with the game that I admire to this day. It was such a well-realized sense of place, and I feel like I've been trying to recreate that with games like Deus Ex or BlackSite, not in the same gameplay style, but in the mood or the contiguous feeling of, "I believe someone lives here. The guy who works here -- I believe that he sits at this counter all day with nothing to do but watch TV."

I think that's a real problem. Even in something as simple as the Sonic the Hedgehog games, when I played Sonic 2 or Sonic CD, there were flowers, little bunnies hopping around, and clouds moving by. I believed that was an environment one could be inside of. As that series moved on, it became less about environment, more about him and his badass attitude or something.

HS: It's almost like this Darwinian thing that happens, where some people come together and try something and it's successful, and that brings in people that are concerned about making sure that it's successful again. With Deus Ex, we included fish in the water. Whenever you jump in the water, there are schools of fish. There are two different kinds of fish, and there are markers in the water that generate them. There's a flocking algorithm, where they swim the right way, and they dart away from you. You can stand on the dock and watch them, and you can jump in, and when you're killing people underwater, there are fish swimming around you. There are rats in the alleys. There are cats on the rooftops.

It's so hard to convince your team about those things. I was recently adding a buzzard to BlackSite, and I wanted buzzards that wheel in the distance in the desert, and when you're driving along, I wanted, 20 yards down the road, buzzards around roadkill. As you get closer, they turn and flap and ascend into the air, and as you get closer, you realize it's a wrecked Humvee, and the roadkill is an American troop. That worked for me on many different levels. Some producer will look at that and be like, "Ambient Animal: Priority Four." And I'm just like, "You don't understand. This is really fucking important. I can't explain to you why." And he's like, "Well, is it more important than fixing this bug in our animation system?" Technically, no! It's a nightmare.

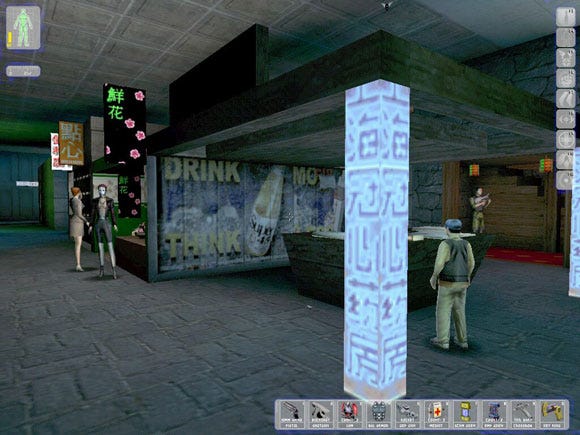

Classic FPS/role-playing hybrid, Deus EX

It's hard, because on one level, I believe that's necessary to advance this as an art. At the same time, only five percent of guys are going to notice and understand why that's cool. That's true of movies, too. If you watch Punch Drunk Love or something, it's a really great movie that had a lot of great technique. You've got Adam Sandler standing just to the side of this beam of light, and he's feeling freaked out, and his face is half-lit, and it's this amazing emotional scene. Most people won't notice what's going on there, but the people who do are like, "Oh my god, that's amazing!" How do we advance this medium as an art if most of the time we have to stick to our budget?

HS: Half the cool shit that happens in the game industry happens because of subversion. You're tracking to one date, and you're working X number of hours per week, but in the background, you're ninja-ing in features. That happens all the freaking time. It's all about when everybody's leaving. Right now, we only work like six hours on Saturday. We're in the final stretch, when everything's finally there, so every day that we have, we can massage the game content, and it makes a tremendous difference.

The game gets better every week. That wasn't true six months ago. It wouldn't have helped to work long hours, because everything was in a nascent state. Most of the time it's not me, it's the other guys, but when everybody's leaving one of our guys is hanging out with another one of our guys, and I'm like, "You know what would be cool? This buzzard thing." We dig through some library somewhere and find a buzzard, and the guy's like, "I can rig this model. It would probably take four hours to hook it up, and I could turn it over to that designer and he could script it into the game." My part is telling them that the buzzard is important in setting up the scene, and explaining why roadkill being a U.S. troop is cool. But they're the ones that have to work the extra hours half the time.

Of course, you're like this guy coming in and saying, "Hey, work ten more hours to do this tiny thing!"

HS: And then he says, "But I just had a baby last month!" "I know dude, but..." It's really like that. One of our guys has triplets, and I don't have children or anything, but I'm told by my friends that do that if you go away for a week and come back, you notice changes in your children. That's how fast they're growing. Denise is my boss, and she just had a baby. She told me the other day, "I get to see Teddy for three hours a day," and I was like, "That sounds horrible! What is wrong with you?" and she was like, "Well, he sleeps a lot, first of all, and three hours is a lot for that age I guess."

She felt guilty, and I said, "Well, you know what? Since he sees you most of the time, he probably dreams about you, so all that time he's sleeping he's probably thinking about you." And she was like, "That actually makes me feel better," and I was like, "Yes! Work this weekend!" (laughs) Half the cool stuff that happens is because someone sacrifices something, and some other group of people is veering off of the budget, the schedule, and the corporate goals.

It's hard that we can't just do stuff until it's done, but if we did, when would stuff ever be done?

HS: Never, yeah. Nature abhors a vacuum. If you give me a salary of X, I'll fill it up. If you give me twice that, I'll fill it up, and I'll be complaining about not having enough money. Similarly, if you give me a year and a half, I'll bitch about it. If you give me three years, I'll be like, "Oh my god, if only we had six more months." Part of it, if you're a good producer -- and I'm not, though I've worked with some, Denise is probably the best producer I've ever worked with -- part of it is getting the team to that point when all the shit is more or less there, so guys like me at the end have the three, four, or six months to put the buzzards on the road.

With Deus Ex, we finished it, and Warren and I said, "We're done; you can play through the game, but characters just vanish. You never see Gunther Hermann ever again after the first three missions. You know what this game needs? Six more months. Let's just go in and write an ending for every character." So Gunther shows back up in Paris, and he has a showdown with you. Before that, he comments to you, "I'm watching you through satellite with my biomod link." We build up, and then we have a showdown. We do that with every character. We had Anna Navarre, instead of just disappearing; there's three different outcomes when she tells you to murder this Russian guy.

It just made a tremendous difference, and it pissed off the publisher to no end. When it came to Invisible War, we needed six more months, and we didn't get it. Everybody bullied us into shipping, and they said, "Aw, six months isn't going to make much difference with this game, and we've got to get it out." We kicked and screamed, but it wasn't enough. Now, I'm pretty much committed to saying I would rather end my career than ship a game too early. I'm not going to be the guy like, "When it's done," because that's also crazy. George Broussard is a friend of mine, and he's been working on the same game for ten years. Fuck that!

It better be good!

HS: I think it will be! But at the same time, I only want to work on stuff that I feel passionate about, whether it's a fast-paced shooter that's very immersive, or an RPG-hybrid that I'd like to get back to at some point, or the game for moms... I never want to be the guy that's about product or ROI or whatever.

With this squad thing, I've always hated games that have squads, precisely for the reason you're talking about. I go and play Ghost Recon Advanced Warfighter or something, and there are these guys. I don't know what to do with them. Every button does five different things, depending on how I press them. I've played it with my coworker, and as far as we can tell, he got killed by a bench. It was absolutely beyond us. But this looks much simpler.

HS: There's a point in the world, and there's a bumper or a button on the keyboard that you'll push, and they'll run over and do the thing they can do there. People give me shit off and on about the left-leaning politics in BlackSite, and I'm like, "Don't you realize that games like the one you just named are implicitly, strongly political?" There's a patriarch figure. You're a good citizen, because you follow orders. The bad guys are the guys in religious garb who are poor. The good guys are the ones with a command infrastructure and the millions of dollars worth of equipment, and are following orders. It's like, oh my god.

And it's good to kill the bad guys.

HS: It's good to kill them, you're right! You're a hero for killing them. We'll give you a medal. I'm not the first person to say that, though. Ian Bell was like this total hippie developer guy. I was hanging out with him in London, and he had ridden his bike to the conference. I'm a vegetarian, and he's a vegetarian. I recently started eating fish again after six years, so I feel suspect in the presence of other vegetarians.

It's okay. I forgive you. Just make sure that it's not from the fish farms and preprocessed, when you can, but that's digressing.

HS: Thanks. Ian Bell is this awesome guy who did the game Elite [with David Braben], the space trader game. He said that he loved Elite, but he only realized years later that he had made an inherently capitalistic game that very much supported the values of the haves having more and more while the have-nots have less and less, because of positive feedback loops that are in economics.

If he had known then what he knows now, he would have tried to balance that, or put in a consequence, or shown you the difference of what happens when one company becomes a mega-monopoly, and buys the rainwater rights for a third-world city-state so they could sell the bottled water or whatever. It's like, how did this happen? It's all about positive feedback loops and emergent economics. Unless we cap it, it'll just keep running.

It feels like it's in some ways hard to educate people about that stuff, but in another way, how better than in a game where you introduce things incrementally, and piecemeal? People get a tiny new bit of information, and then discover what that does.

HS: I would like to feel like at some point that BlackSite is a turning of the tide in the mainstream. I've felt the way I feel for a long time about Bush and Cheney and Rumsfeld, and Wolfowitz and all those fucking evil bastards. I said in London recently that our government is full of monsters. I could go on and on, but the problem with the privatized future -- which I think is the future of America -- is that sure, commerce can do things more efficiently, but that is putting the value of efficiency above all other values.

There was this great story from a California town that privatized their traffic lights. They wanted somebody to come in and put cameras on all the traffic lights, and this company said, "We can do that, but we have to take control of the traffic lights." And this is a new thing, a corporation controlling the traffic lights -- wild, right? So they did it, and it worked beautifully. Every light in the city was new, and they all had a camera for accidents. It was great, except that the injury and death rates started to rise, and they couldn't figure out why. What happened is that the company figured out that if they tweaked the algorithm around yellow light duration, people couldn't coast through a yellow light as easily, and they'd get tickets, and the company would get more money, because they made money for every ticket. Of course, it also created more accidents, so it's a great example.

I want some things controlled by the free market. That's something I want controlled by a government entity, even if it's bureaucratic, because the number one value of it would be safety and not profit. So I agree, that incremental thing is a good point. I don't know if you know George Lakoff -- he wrote Don't Think of an Elephant, which is a brilliant 100-page book that I think everyone ought to read. It talks about how the world divides into either the strict father mental model, or the nurturing parent model, and they have different values. You can never make sense to the other person, because your values are fundamentally different.

I got to exchange mail with him during that eight-month period when I was unemployed. I was so furious about politics that I exchanged mail with him, and said, "Hey, I have this idea for this game." It's like SimCity, kind of. It lets you run a country for a while, and you're allowed to implement policies in either direction. You can be like, "Hey, you committed a crime. You've got to go to prison. While you're in prison, you're going to get a high school degree, then a college degree, and we're going to give you job skills and make you work out every day. It's very socialistic, but we're going to make it as pleasant a place as possible. It's not going to be gray, and you won't be raped in the shower. You're going to come out with a sense of confidence. You're educated. You're a craftsman. We're going to rehabilitate you."

On the other hand, you're free in your country to implement a policy that's like, "Throw the key away. Punish those bastards with stricter and longer sentencing, and then let's run it a few generations and see what happens. Let's take the data as objectively as we can." What happens to the recidivism rates in the countries that rehabilitate, versus what happens in the country where you go to prison for ten years if you smoke pot?

So like America versus Sweden, or something?

HS: Exactly! Let's see what happens. Let people win the game by doing the right thing, was kind of my thought. He was a really fun guy to talk to, and he turned me on to some companies like MoveOn.org who said, "We're too busy trying to win the election right now!" I wish they had funded me instead of doing whatever they did during the election! But I agree with the comment about the incremental approach, and I don't think you can yell at people and say, "This is how you ought to be!" I think you just have to say, "Here's a story, and here's a moral tale," and they get that.

As long as you make people consider consequences. You can't turn a Republican into a Democrat by playing a video game, but you can make someone think about stuff. You can make them think about issues, and make them think, "Oh hey, I feel like I should've done something there." One thing that really gets me is V for Vendetta. Did you see it?

HS: Brilliant!

It was one of the most politically charged movies I've seen in so long. Power to the people... it was amazing, and nothing happened from that. No one cared! Rooms were packed with all the right kind of people, like the people who don't think about this stuff, and they continued not thinking about it.

HS: "That guy's pretty badass with those knives!" (laughs) Yeah, it's funny. Even pointing out to someone, like we did in Deus Ex -- and we talk about this a little in BlackSite, but it's not a role-playing game -- how our government funds somebody one year and then sends troops to fight them the next year, is very expensive. One year they call them freedom fighters. The next, they call them terrorists. It's the same fucking group of people. That can go totally unnoticed unless you point out to someone: In terms of cognitive linguistics, there's a frame going on here, where "freedom fighter" says all the right shit. I want to support freedom fighters. Who doesn't? I want to be a freedom fighter! "Terrorist" is [bad]. And they're the same guys. It's like people are controlling you. We're all these little machines that can be lit up in certain ways.

A while back, Bush was talking about Iraq and why we should go there, because they were under control of a despot. He was saying that a free country does not exploit its people, and does not develop weapons of mass destruction.

HS: A free country does not torture. This is all ironic.

He said all that crazy stuff, and it's like, you're talking about all the things that we're doing. People won't pick up on that unless there's something like The Daily Show to pick out the irony.

HS: Which is why you've got to love Jon Stewart. But the problem is that he's preaching to the choir -- people like you and me.

That's why something like this game has a lot of potential. You're preaching to the guys who play first-person shooters.

HS: That's kind of why we use the word "subversive" a lot. We don't want to be The Daily Show version of a game, or the angry liberal version of a game. We want to be a badass Delta Force shooter, where you're Aaron Pierce, who is a thoughtful but quiet guy. Slowly over time, we have characters who are gung-ho who become a little less gung-ho. Even in funny one-liners. Noah, the Middle Eastern intel specialist, is your squadmate for a while, and has to give you an injection. Someone asks, "What is this for?" and she says, "It's classified. I can't tell you." Later, Grayson jokes, "Hey, I think I'm growing a third head over here," or whatever he says, and it's just this one-off joke. Later, she says something about safe, and the line is like, "Yeah, you'd never give any dangerous shit to a soldier, right?"

I was in the military for six years, and to go to Saudi, I got shots that I don't even know what the fuck they were. Like, "What is this?" "It's GG." "It's cold. It's like syrup." "Well, we just took it out of the fridge." "Well can you rub it under your arm?" That's what the nurses would do, and then they'd give it to you, and it would sit under your skin in a lump. What the fuck is this? Is it FDA-approved? No! It's experimental, technically. Even the flu shots we got were experimental. It was part of the FDA testing, actually, to test it on soldiers.

I was kind of naive back then, so I was like, "Okay, I guess it'll protect me from something -- diarrhea in the desert, or whatever the fuck I'm afraid of." It seems like over time -- if you take into account Gulf War Syndrome and Agent Orange and the stuff in the '60s or '70s -- I can never remember that drug that they put in formula for babies that caused deformities, and the number of babies with extra arms and legs skyrocketed -- clearly, in trying to pursue profit, companies will just utterly eradicate human lives. The government is no different from that, and you just have to be on guard.

The government is no different from a corporation in many ways. We're derailing a bit, but it's tough to feel like you have any effect on anything that goes on in your life. It's like, I can elect this guy, or this guy. Who knows if my vote's going to be counted, and who knows if this guy will do what he says he's going to do? Tomorrow he'll say something else.

HS: And the commercial that I just cheered for my guy, who paid for that? Did big pharma pay for that, or did the fast food lobby that's killing everybody in America pay for that?

Another question about the squad thing -- you've got the emotions for the characters in morale. Is it an off-and-on for emotions, or is it an algorithm?

HS: It's definitely an algorithm. Points go into a pool based on the things you're doing, and how well you're doing, and whether you're giving orders, making headshots, or missing or hitting. It's whether you're letting your guys take damage. At the peak of it, their tactics change, their facial expressions visually change, and their postures change, and they will race out into combat much more aggressively. They melee more. On the backend, they start taking cover more often, firing less often, and complaining. They have facial expressions, and they blindfire over cover more.

There's a lot of cool emergent stuff in games I think that you can build systems on. We have breakable cover. We have Mini D compared to Stranglehold's Massive D. It's mostly combat cover objects. If the squad goes into low morale, they start taking cover behind stuff, like this bench, and a sniper hits it and it crumbles. You see more breakables because morale went into a low state. It's really cool and unexpected -- who thought that would happen? Similarly, we have a recharging health model.

It does do a recharging thing, but it also has a layer of armor on top of it, so if you find kevlar, you don't take any damage until the kevlar's gone. That allows us to make comments about Rumsfeld's style -- not sending the troops to war with enough armor, and that sort of thing. But what happens is, when you're badly damaged -- you're breathing heavy, the screen turns red, and you want to take cover -- you tend to crouch behind something, which causes the enemies to shoot that. So you see shit breaking all around you. We didn't expect that at all, either. The two just work together like that.

How do you transition between animations? How sudden is that?

HS: Art Mann is an AI programmer that I've been working with off and on since I was a tester on System Shock and he was a coder. He worked on Team Fortress 2 for a while, and worked on FireTeam and Deus Ex: Invisible War. He's a solid guy, MIT grad, and he's the one largely writing the morale system. It just keys into a whole bunch of states, and those states key into a bunch of animation sets, like the facial expressions, the body postures, how frequently they look for cover, and how far away from Pierce they're willing to get.

Is the transition actually smooth?

HS: Sometimes it's abrupt. Sometimes they go from, "Wow, we're kicking ass now!" to "Hey, this isn't going so well," to "Oh my god, get me out of here!" but that's like if a grenade lands on his head and knocks his squadmate down, and you're just standing there doing nothing. All of a sudden, the game gets more difficult by twenty percent.

The more stuff like that you put in, the more miscreants are going to find some really embarrassing crap.

HS: Right. [Squadmates] hiding behind a gas tank, or something.

Which is funny, to be sure, but I'm sure it doesn't make you feel great to see it happen.

HS: I've always liked that. What you've got to remember is that some huge percentage like 95 or more of people, if they like the game, are sympathetic players. They try to make it work the way it works. If you fuck them -- if the game sucks, or runs at five frames a second, or is tuned badly so it takes five clips to kill a guy -- they become unsympathetic players, and they rebel. The game gets worse for them. It's another positive feedback loop. But 95 percent of players or more are trying to play the game and get enjoyment out of it. I have been that perverse guy, too. That's one of the reasons in Deus Ex that we did the multiple solutions to problems thing.

We all wanted to try to break the systems and see how they worked. Some guy in Deus Ex figured out that you could take a proximity mine and put it on the wall and hop up on it. It had a little lip of physics. Then you could place another one and hop up on it, then turn around, crouch, grab the first mine, and put it up higher. He would just climb out of the world that way. He'd climb the side of tall buildings that we never intended anyone to be on top of. It must've taken hours. But then he would take screenshots from places he wasn't supposed to be. That guy is such a small percentage of the industry, but it's so clever, and it's such a creative use of the game. It's a metagame, at some level. You've just got to applaud that.

When they stopped making games that I really enjoy -- and I hope that they come back to those -- that's how I started playing games. Just screwing around, and getting outside of the map in Gears of War and things like that.

HS: We had this German fan for Deus Ex who read some interview or something where we said someone had somehow seen through the wall of the world. Very often, when we were building levels, the whole world was a solid, and you'd subtract a pocket and build the city street in it or whatever. Right on the other side of it, we'd subtract the pocket, and we'd put down one of every type of furniture object or whatever.

So there's this odd little cube in an otherwise solid plane of existence with stars on top and living room walls on the side, and maybe one wall that's nothing but fish swimming around, and weird pieces of furniture. It's very surreal. It's like, "This is where the god of this city street lives." Someone found something, or we told somebody about it, and we kept getting letters from this German fan looking for how to get to that in the game. Maybe there had been some mistranslation, or something. It's definitely true that there are people out there that just want to, as Will Wright put it, "Play with the possibility space."

They want to find whatever there is to find.

HS: The boundary, right.

It also plays into what Cliffy B. said in an interview I did with him, which was something like, "Never underestimate the ability of the user to undermine the narrative you're trying to tell."

HS: Yeah, totally.

If you give people stuff to do, they're going to do some weird stuff.

HS: Expectations were so low for BlackSite initially, then slowly climbed as people realized, "Oh, this is the kind of shooter they're making, and here is the feature set, and... oh, wow, looks pretty fucking good." Then people played the demo, and the demo is based on really old code, but it was five minutes of interesting, immersive shooter stuff, I think. In the demo, this giant fucking thing crashes through a strip mall and rises up and roars, and it's about to spawn all these enemies, and we fade to black. And the last line -- one of the morale lines -- is, "This is going to be bad."

We had a meeting at midnight one night before released it, where we said, "Should we end our demo on a line that says, 'This is going to be bad?'" And somebody went, "Fuck you! That's a trivial concern," I don't know whether I thought it was that big of a concern, either, and it actually wasn't. But somebody, invariably, will point out that's probably not a good way to end your demo. It's like, "Well, you're part of the 0.1% of people who would think that, and you probably didn't dwell on it very long anyway."

Someone could make a YouTube video [out of that].

HS: The YouTube video I wanted somebody to make so badly is all footage of President Bush at a press conference, and a fake reporter in the crowd saying, "Sir, do you realize that your popularity rating is as low as any President in history? Currently as low as Nixon. Do you realize there are even video games that are mocking your administration?" Then you'd cut some footage of Bush together where he's like, "What are you talking about?" And the guy's like, "Well sir, there's this game called BlackSite. Have you played it yet?" And then go back to Bush and he's like, "No, I don't think I have. I don't think I know what you're talking about." Just putting together a fake press conference. If I had time to do that, it would be so awesome.

Get the marketing people on it!

HS: Nah. I think it would be fantastic, but it's not going to happen.

It would be! I think it's good to be going for that kind of stuff. Was it your idea to turn it into this sort of thing?

HS: Yeah, like I said, a year ago, this project was in trouble.

Until you said, "Just give me carte blanche to do this weird thing?"

HS: Not necessarily carte blanche, because I never get that, but I said, "Hey, look. This is a one-page story treatment. Do you like it, or not?" And all of the execs were like, "Wow, this is the most exciting thing we've heard around this game." I said, "Here are the four or five things that I think are going to be important." I kept driving to those points, and sometimes people don't get it. Some people can see it, and some people can't. When we could demonstrate it, everybody got it. It was like, "Oh, it's this kind of shooter with Unreal tech, and I get why squad morale with one single button is as easy to use as a pistol."

Initially, they were like, "Squad, oh god, terrible. Serious hardcore military shooter menus, confusion, not mass-market, and yada-yada-yada." That's not what we were talking about. And then morale... some U.S. journalist thought we said "moral," and wrote an entire article about how we were going to have a moral system in the game. We were getting on the phone saying, "Correct this guy, please. Don't set up false expectations for what kind of game we're making."

Those are not all my ideas. Those come from working with a cabal of people on a team who are pushing certain things. Often, I drive an idea or come up with an idea, or as soon as I hear it, I steal it. I'm like, "That's important!" "How do you know it's important?" "I don't know!" It's just a compass that I have that says, "That's important," and I could be wrong, or I could be right, but that's the way we're going. As long as I can control the steering wheel to some extent, we're going to go for that.

There are people on the team who are like, "That's going to be offensive," or "That's going to cause problems," or "The squad morale is not going to be cool or interesting." Everybody points out every possible problem. "Well, if the game makes it harder when you're doing poorly, doesn't that make it even harder and then you do more poorly?" "Yes, that's called a positive feedback loop. We'll correct for that, don't worry." But then there's like a hundred reasons not to do any one thing, and you have to pick the five. If somebody's not driving to a vision, your game just ends up some random bullshit video game.

There are a lot of those. With the squad thing, it seems like component by component, people are taking previously difficult elements of gameplay and making them work for a larger group of people. It doesn't really seem to be making the market casual or not hardcore enough, necessarily. It doesn't give you that crazy ridiculous level [of detail], but those [hardcore] people are such a minority anyway in some ways.

HS: Yeah. The two games I'm playing right now are Dungeon Runners -- the most casual game ever, in terms of being in an MMO you can play right now -- and S.T.A.L.K.E.R., the hardest-core PC game that you can be playing right now. Those are the two games I love right now. Last year, my favorite game was Dead Rising. There was something else in the list from last year, too. I always cited three things last year: Dead Rising, Gears of War for its art direction, and something else.

Resident Evil 4 has been my game of the year for about three years now.

HS: A lot of people love Resident Evil 4. S.T.A.L.K.E.R. right now is so awesome, but you know, there are a very small number of us who would actually go through the lengths of getting in the vibe of S.T.A.L.K.E.R., and the main thing I get out of it is this sad, sad atmosphere.

I love playing cat-and-mouse with their AI, and I'm totally into the fiction. I love power-balancing the artifacts that you can carry. But that's a small number [of people], you know? I really do believe that with every generation of games, we have the opportunity to open up somebody's eyes again, the way mine were when I was ten and my neighbor got a Pong machine or something. One thing after another was just eye-opening, and there's never a shortage of new gamers who probably haven't played a story-based shooter before. They weren't there to play speakerphone Doom like I did with my office comrades, so co-op games to them with voice chat is really powerful. To me, it's like, "Yeah, this is a familiar experience I love," and then I'll run out of steam for other things. I can't play another RTS for maybe ever, because I went through all of them, and worked on one for awhile.

Having been in the military, did that affect how you saw this?

HS: I don't know. I spent six years as a satellite communications guy in the Air Force. I lived in a German farming village three and a half years, which was super fucking cool. I went to Saudi for a month, over Thanksgiving one year between the two Gulf Wars. I was in Germany during the first Gulf War, and I had a great fucking time. I didn't get along with the establishment, but I got along with plenty of the people that I worked with, because they're just fun guys, at the end of the day.

It wasn't the kind of bullshit that people are having to deal with right now?

HS: No. It was also the Air Force, which was very different. I deliberately went into the Air Force, because it wasn't being a ground-pounder, or whatever. You're allowed to have a personality in the Air Force. I was also a satellite communications guy, which is one of two jobs: it's either all about being in a concrete bunker five stories underground -- there's a metal shack with an elevator, and the ground above it is concrete blocks the size of a Volkswagen, broken up in irregular pieces so that if a nuke goes off, they shuffle and distribute the force, instead of fucking up the base underground.

It's either that job, digging a ditch, or it's driving a van to this hotel somewhere, going up on the roof, setting up a dish, running a cable down to a general's office, running another cable from the radio to the van downstairs, and he's got a phone line now where he can turn a key and talk to anyone in the world, totally secure. That's the tactical part of the job. That's what we did in Saudi.

We did the other one in Germany. I had a great time. I'm from a really poor blue-collar family. There's all this shit in my family that's unbelievable. So I didn't go to college or anything. But I was an English Lit major with the University of Maryland because of the Air Force. Five years on it are very different than the trust fund kid who went to Berkeley and now looks down his nose at the military or whatever. Hope you're not a trust fund kid who went to Berkeley!

I was actually born in Berkeley, but I was very far from a trust fund kid! We were on food stamps till I was five, so don't worry. Our narrow view on the military comes from my parents being hippies their whole lives.

HS: My dad was a redneck. My mom was a wild child, hippie '70s girl. That led to a lot of interesting culture clash in my life, very early on. But I feel like I have a grounded view of it. Like I don't have the "baby-killer" view of [the military], but I don't have the "rah-rah patriotism" view of it either.

Do you think if someone played this game, or a game like it, when they were 16, would they understand what they were getting into? There's a lot of people who think, "Yeah, we're fucking America!"

HS: No, I think that almost all action movies, novels, or games, at the end of the day, they romanticize to some extent the role of the warrior. It's hard not to. Even in some of my favorite books -- you can take a book like Lord of the Flies, which is about, "Is violence inherent in man? Without order, here's what we devolve into." You can actually read it as a middle-school kid going like, "I want to be like Jack on the island! I'm the guy with the spear kicking ass on Piggy!" You can take that away from it if that's what you want.

It's tough. You can't make people into something else, which is one reason why I don't think this whole video game violence thing holds too much water. There's something to making people think that it's easy to kill, because it is easy to kill.

HS: One of my favorite examples comes from Warren Spector, who always points out that there's a big difference between violence and aggressive play. Aggressive play is something that everybody engages in. When you're a kid, you swordfight, or run around playing Army, or you wrestle. Lion cubs bite each other and roll around. They're not trying to hurt each other, clearly. Violence is trying to hurt another person, and aggressive play is a healthy, natural part of life. Violence is also a part of life, but is not healthy, and we should watch out for it. Video games are aggressive play. That's the way I look at it. The military, actually, is violent!

It's weird when those two meet. You've got politicians saying that it's really bad, and then you've got the America's Army game funded by America's Army, and getting kids to be interested in being in the Army.

HS: Or even worse, accepting a particular world view. It goes deeper than that.

There are some difficult issues there, that's for sure.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like