Josh Wardle reflects on the the unconventional road to Wordle's successJosh Wardle reflects on the the unconventional road to Wordle's success

The story of Wordle is a tale built around doing several things that game developers generally are not meant to do. Here's how breaking the "rules" allowed Josh Wardle to create a simple but clever game that had a surprisingly huge impact on its players.

"I don't think of myself as a game developer at all. So I kind of want to be upfront about that."

That's one of the earliest bits of insight shared during Wordle creator Josh Wardle's talk at GDC 2022, a talk that nonetheless had a room of game developers routinely nodding along in agreement and eager to hear Wardle's thoughts on everything from monetization to the ways in which games exist and interact with the world around them.

Still, Wardle maintains that the game's creation, and his own unlikely path to a stage at a conference about the ins and outs of being a game developer, really only came about because he ended up doing "a bunch of things that you're really not meant to do at all."

Wordle itself is a charming little word game that exists across audiences and generations, first starting out as something Wardle made for his partner's entertainment and later becoming a game tweeted about by celebrities and eventually sold to the New York Times for a figure "in the low seven figures". In it, players have six guesses to figure out the word of the day, with a straightforward, color-coded feedback helping to craft their guesses along the way. All in all, Wardle says its an admittedly simple game, but still calls out the core premise as one of those so-called mistakes.

"This is the first thing I did that I think you're not meant to do: I made a word game," said Wardle. "I think when you think about viral, exciting games you don't think about word games. Which is kind of sad to me."

However, he argues that word games have an inherent advantage over other kinds of projects. To illustrate that, he calls back to a quote from the literary theorist Terry Eagleton, which reads "language is the very air I breathe."

"What he means by this is that humans are creatures of language. Every experience we have is mediated through language, every thought we had is through language, and words are a subset of that," says Wardle. "So the way I think about that in terms of a game is that imagine if you make words the core mechanic of your game, everyone comes to your game already having a deep, deep understanding of the most fundamental part of your game."

From concept to prototype

The idea for Wordle came back in 2013 originally when Wardle, like many of us, were head over heels for Words with Friends. Wanting to try his own hands at making a word game, Wardle thought back to a game he'd played as a child called Mastermind that tasked players with guessing a sequence of colors, giving them small bits of feedback after every guess to steer them toward victory.

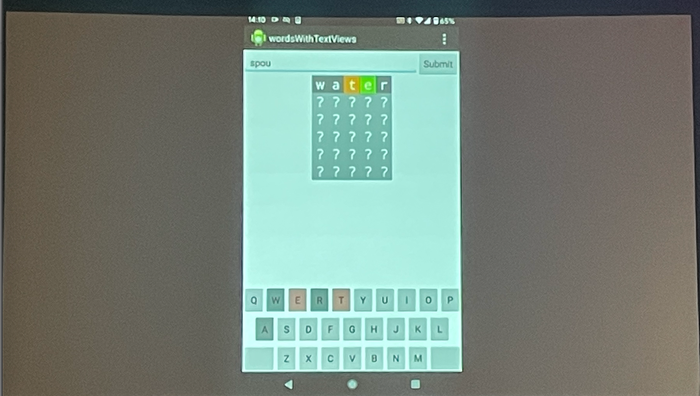

That simple merging of ideas lead to the very first prototype of Wordle ("I tried to teach myself android development; it looks like garbage."), which Wardle notes is visually similar to modern Wordle but features two key differences: endless play, and a excessively expansive library of potential words to guess.

"There are around [13,000] 5 letter words in the dictionary that I'm using," he explains. "And the way this version works [is] it just picks one of those at random and that's the one you're guessing."

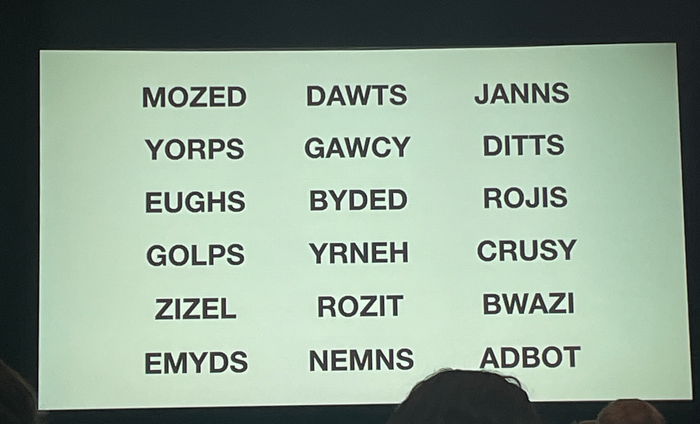

"It turns out that these are all valid five letter words in the English language. I have no idea what any of them mean, and I kind of love that. But at the same time, it was kind of clear to me that if you were trying to guess a word that you'd never heard of, the game became more like Mastermind right? When you're guessing that color pattern, and the colors don't have any relationship to one another."

"What's fun about Wordle I think is where you can kind of tease out based on what you know about language what the word should be."

The next step then became finding a way to whittle down a list of 13,000 words into ones that were familiar enough to support the very familiar and language driven premise of the game. Wardle first took a stab at using algorithms to curate the word list, but he wasn't happy with the result and abandoned that approach.

The solution, oddly enough, was to create what arguably could be another game. Through another expertly developed app, Wardle set up a system that would take all 13,000 of those 5-letter words and present them one at a time, allowing his wife to categorize each as either a word she'd heard of, one she'd didn't know, and one that sounded familiar.

"I think often people look at Wordle and the reasons for it being successful," says Wardle. "But the thing where you know, when you're playing the game, that the answer's going to be a word that you've likely heard is really, really important. Especially for a first time player. If you come to the game, and you're trying to guess a hidden word and its a word you've never really heard of before, I think you feel like you've been cheated by the game. This is something I thought was really important."

The other notable change to the Wordle formula came in 2021 (after the original project was briefly abandoned) and was interestingly prompted by the way the New York Times handles its word games. For both the NYT Crossword and for a game called Spelling Bee, you're only able to play them once per day.

"I think that's something you're not meant to do, especially with mobile games, right? Like I think that there's this expectation that you just give the person what they want, which is to play endlessly, and as soon as they're done move on to the next one, and the next one. I don't really like that."

"I just wanted a game that was just three minutes of your time a day, and that's it. That's all it wanted from you."

He goes on to explain that this one limitation actually very subtly introduced a social element into the game. Players could talk to others about their experience playing, share their triumphs or bemoan the double L that kept them from solving the puzzle.

"That ended up being a huge part of the game and something, frankly, that I wasn't intentional about it."

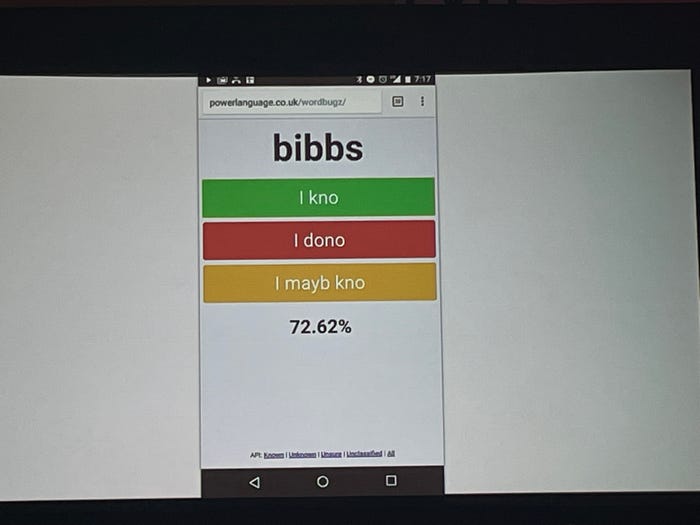

Armed with those two principles, and a newfound skillset in web development, Wardle created a new prototype for Wordle that's visually much more similar to what most of us have seen on our computers and phones.

Building on Wordle's social elements

On the wider web, Wordle was something like a secret sensation. All at once, Twitter timelines and Facebook feeds were speckled with a cryptic series of words, numbers, and emoji, with no further context or no link trying to use viral sharability to pull you into the game. Those messages were a grid of square emoji, where grey, yellow, and green shapes identified how a player had fared in that day's daily Wordle puzzle. Like within the game itself, yellow implied a letter should be placed elsewhere, grey meant that the letter wasn't present in the word, and green told players their guess was correct.

Way before that, however, Wordle was still a game played only by Wardle and his partner. There were no specific social features built into it, and no clever way to share that day's results. After six months of playing, they started introducing the little web-based word game to their families.

"I told my family about it and they started playing, and something really interesting happens with my sister-in-law. Her family have a group chat, as I'm sure most of us do with our family, and it kind of died down. Wordle reinvigorated it somehow."

On that small scale, Wardle saw the social elements of Wordle spring to life as family members routinely started starting their daily conversations with a quick "oh I solved today's Wordle in three," but he admits he didn't fully understand the implications of that sharability at the time. Interestingly, the game's early community was the first group to truly tap into the sharable nature of the game, with one such player inspiring the grid-based social sharing system that has now become so synonymous with the Wordle experience.

"A player who's playing the game comes up with this way of sharing her results where she goes to the emoji keyboard and types out the grid on the board. And I see a bunch of other people popping up, doing the same thing: taking the time to open the emoji keyboard and typing out their grid. So I Implemented it into the game."

"What's interesting here is previously you have the shared experience with Wordle; you're all playing the same game, the same word every day. But when you play Wordle by yourself you go on a journey. There's a series of steps where you think you're going to guess it and then you don't. And this emoji grid becomes a way in which you can share that story really easily with others."

Wardle points out that he did receive some criticism via Twitter along the lines of "What is this guy doing?" for not baking the URL for the game into the emoji grids that players could push to social media. To developers designing specifically to try and capture a viral audience, doing so would seem like a no-brainer. But for Wardle, adding a URL into the system wasn't really something he considered a good idea for a couple of reasons.

When you play Wordle by yourself you go on a journey. There's a series of steps where you think you're going to guess it and then you don't. And this emoji grid becomes a way in which you can share that story really easily with others."

"One, the grid has this really beautiful, simple aesthetic and if you throw up a link there It kind of looks crappy in my opinion," he explains. "The other is one is that I felt really uncomfortable that if the game has an agenda to get you to share, because it means more people will come and play the game... Like why am I encouraging people to share? Am I encouraging them because they want to do it? Or am I encouraging because it's good for the game."

"But it had this flip side, in that these cryptic things started appearing over Twitter and people were like 'well what is that?' and it kind of became a club that you're either part of or not part of."

Things You Are Not Meant To Do

The end to Wardle's time with Wordle of course came via a flashy sale of the game to the New York Times, an apt conclusion given that NYT puzzles were so central to the game's very creation. But, similar to Wardle's claim that he's not really much of a game developer type, there were a good handful of other reasons he ultimately decided not to hold on to the game and manage it going forward.

"I made this game but I had no interesting running a game business. I think of myself as an artist, I really enjoy creating things. Running a game business is not interesting to me." Despite not wanting to monetize Wordle himself, he still says there was a "deeply unpleasant" feeling for him surrounding the number of clones that copy-pasted the game and added in monetization schemes to make a quick buck. He didn't want those games to eek in on what Wordle meant, but he couldn't see himself getting involved in legal work it would take to combat them. Clones weren't the reason for his decision to sell, but the "a way for me to walk away from that."

Clones aside, he does have many fond things to say about the game's playerbase and the way it has been able to become such a core part of people's lives and experiences. During the talk, he shared heartfelt messages he'd received from players who were able to reconnect with estranged family members through playing the game, different creative spins on the Worlde formula created by other game developers, and a video where a room of third graders erupted into cheers when they solved a projected game of Worlde in the classroom.

Running a business ranked among Wardle's list of Things You Are Not Meant To Do throughout his presentation, outlining ways in which Wordle shouldn't have really found the success he did or why it was fundamentally strange for Wardle himself to be at the center of it. But despite not considering himself a game developer, or never wanting to be at the center of a game business, he seems genuinely happy with what something like a simple word game has become for so many people in the world.

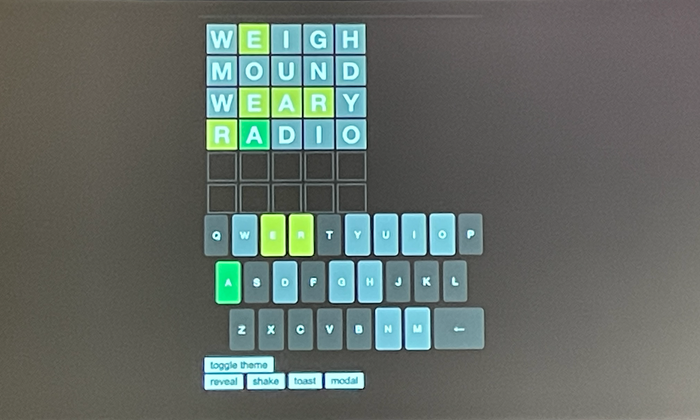

And, just so other game developers know what not to do, here's Wardle's list of Things You Are Not Meant To (that he for sure entirely did):

#1 - Make A Word Game

#2 - You Can Only Play Once A Day

#3 - Host on a Website, not an App

#4 - Have a Terrible URL

#5 - The Game Did Not Promote Itself

#6 - Did Not Want to Run A Games Business

#7 - Did Not Monetize The Game

Read more about:

FeaturesAbout the Author

You May Also Like