Take a peek inside the level design process of Horizon Forbidden WestTake a peek inside the level design process of Horizon Forbidden West

Here's what goes into designing a single major level of Horizon Forbidden West.

Horizon Forbidden West is a HUGE sequel to the already-enormous Horizon Zero Dawn. Designing any one part of this massive open world involves working on features that intersect with so many other game elements.

When building major levels that bridge huge parts of the game's story, that ask becomes even more challenging. At GDC 2022, Guerrilla Games senior quest designer Blake Rebouche did a breakdown of the quest "Death's Door," a major early level that propels the plot forward and introduces players to a number of key mechanics.

Death's Door took literal years to complete, and was constantly impacted by design improvements in different departments. Here's a small taste of how Rebouche and his colleagues managed all of those intersecting design challenges. Some of his solutions might help your team on their next big game.

Bunker Buster

Rebouche began work on Death's Door after its core narrative hook was locked down by the narrative team and creative director. The conceit of the level stayed mostly complete from start of work to finish.

Protagonist Aloy enters a massive bunker searching for a backup copy of an AI named Gaia. She passes through offices used by Gaia's creators, recovers the AI, but then is attacked by a new set of futuristic villains with new kinds of machine enemies. She flees the bunker, using new underwater stealth mechanics to avoid capture.

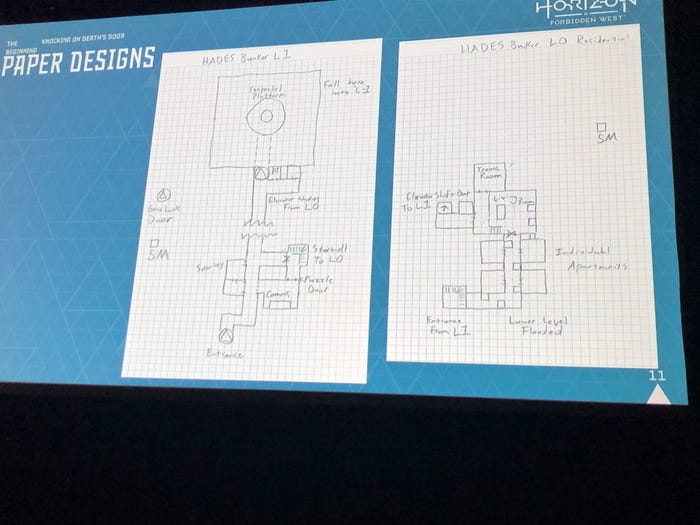

Rebouche's level design process will look familiar for seasoned hands. First, he and the team sketch out paper prototypes. Then they block out a skeleton version of the level to flesh out gameplay ideas. After that, a "first playable" version of the quest is assembled that's ready for playtest feedback. Then it's a long process of iteration and parallel development until it's time to ship.

Rebouche's top-level goals for Death's Door were built on lessons from working on the bunkers of Horizon Zero Dawn. he and his team wanted to build story-rich environments, reduce combat against human enemies (this was rated very negatively in the first game), and reduce art/lighting costs.

Before Rebouche even created the paper prototype, he created a beat sheet inspired by the narrative direction given, and spelled out what gameplay elements he wanted to create to emphasize the level's narrative goals.

When showing off the greyboxed version of Death's Door to the GDC crowd, Rebouche explained that in this phase, the level design team deliberately puts bright colors on pathways and objects required to complete the quest. Since the level is not ready for an art pass at this stage, calling out key features with bright colors helps the team understand the level's flow.

In parsing that flow, Rebouche also began writing "self-talk" dialogue prompts for Aloy that would be passed back to the narrative team for iteration. Rebouche called out that this was never meant to be narrative dialogue, but instead would organically serve to help nudge players through certain puzzles.

One challenge the level design team faced in creating Death's Door was that the Specters (the new machine enemies brought in by the game's villains) would not be finalized for YEARS in production. Though they're not combat enemies in this zone, they're supposed to be stalking and tracking the player during the climactic stake.

Rebouche didn't sweat this. "I used human enemies from the first game with lasers on their faces," he said (with a straight face). These goofy-looking goons would spend years stalking this section until the Specters were designed.

First Playable Problems

Moving from the skeleton prototype to the "first playable" version, Rebouche brought up the many changes made to the level's final encounter. After recovering GAIA from a spider-like computer machine, Aloy is attacked by an invincible opponent, and overcomes them by tearing the spider's legs off the wall and sending it collapsing to the ground.

Playtesting in the first playable level illustrated an early problem with this plan. All of the first prototypes for attacking the spider locked players' focus on this big machine, meaning they didn't interact with the boss.

Rebouche tried moving the tear points to the nearby walls to fix this problem, which kind of worked, but over time he would realize players didn't get any chance to interact with this one-of-a-kind creation that felt true to the world.

Pulling down the spider's limbs required use of the Pullcaster (a new tool introduced in the game's first hour that lets players grapple to objects or pull objects toward them). Using the Pullcaster to solve puzzles became a central focus of all of Death's Door, but further playtesting illustrated a problem that's likely familiar to open-world designers: Players sometimes forgot how to use this tool, even though it had been in their inventory for hours.

That's because in an open-world game, players could easily have spent hours not using the tool by now. Here Rebouche shared one of his new golden rules for level design: "The Golden Nugget."

"Nuggets" in Rebouche's vocabulary now refer to little "teaching" moments that help players remember how to use game mechanics. Rebouche would go back to the level's start to add these nuggets for many tools that came in during development, including the Shieldwing Glider.

He credited the "nugget" idea as coming from one of his colleagues who joined the team from Eidos Montreal. One of these implemented puzzles was a "charged spear" system that would later evolve into a battery puzzle, where players had to charge up empty batteries and pull objects into place to carry them across water to a receptacle.

This puzzle served as a "nugget" for both the pullcaster movement and charge system. But the space it lived in would become dramatically reshaped by what happened next.

The costs of iteration

Rebouche's electricity puzzle lived in a section of Death's Door he referred to as the "underwater labs" section. For a long time, it was anchored around underwater navigation, and was meant to feel like "cave diving" in this tech-filled bunker.

It was cut for two reasons. First, Rebouche received higher-level direction that they wanted more Pullcaster and Shieldwing Glider segments (this happened right as the COVID-19 pandemic started).

The Shieldwing Glider in action in a later section

Second, the underwater level environment in this space was so poorly rated by playtesters, that footage of Rebouche's level was used in an internal document spelling out how not to do underwater traversal.

Rebouche's design space was also impacted here by other art and design departments completing assets or mechanics and having them inserted into the area. Hallways were stretched and shrunk. Traversal tools were added, and playtesters began telling the team where they had no clue what was going on.

This iteration helped Rebouche solve the aforementioned problems with the spider room boss. Tech artists and other designers came in to create unique objects on the spider-shaped machine that could move around the space.

Rebouche called out that this actually reverted the overall boss fight to a state close its original prototype, where players ignored the boss in favor of the machine. But because of improvements to the boss AI and more dynamic movement in the machine's shootable parts, it came together in an unusual fashion.

This was slightly unusual, Rebouche noted, because most design iteration takes developers away from flawed prototypes and toward fun interactions. But here, the flawed prototype had the bones of the "right" encounter...they just weren't obvious without other departments.

The level's underwater stealth climax finally received much-needed attention too, as the Specters' design was finalized and they were added to the level. Though most underwater traversal for the level was cut, Rebouche kept one very useful trick here.

The players' oxygen meter for underwater traversal allowed them to stay submerged for a fixed length of time. By timing the hallways' length to match that meter's maximum level, players were forced to surface for air in a room filled with Specters. It was a great tool for ensuring the new creatures had their time to shine.

By the time Death's Door was ready to ship, it had seen so much evolution even though the story beats it communicated stayed the same. Looking back at the process, Rebouche said he appreciated the fact that the level's story had been so consistent, that the level's early prototypes had been so readable and representative, and that his team could shift so well when larger design changes came to the game.

And with so many cut ideas reappearing elsewhere in Horizon Forbidden West, Rebouche ended his talk with one final thought for level designers: "Good ideas are like boomerangs," he said. "Even when you throw them away, they often come back."

Read more about:

FeaturesAbout the Author

You May Also Like