How improv acting and classic Asian storytelling influenced The Last of Us Part IIHow improv acting and classic Asian storytelling influenced The Last of Us Part II

Naughty Dog level designer Evan Hill breaks down the process for perfecting The Last of Us Part II's museum flashback level.

In the world of improv acting, two simple words can get you anywhere: "Yes, and…." In the world of Naughty Dog's The Last of Us Part II, those words can give you one of the most emotionally impactful moments of 2020, and make for optional content that packs as much punch as any linear story beat.

At GDC 2022, former Naughty Dog level designer Evan Hill (now at Obsidian Entertainment) walked developers through how improv, a traditional Japanese storytelling tool, and good old fashioned iteration helped build The Last of Us Part II's museum flashback.

In said flashback, protagonist Ellie and surrogate father figure Joel venture out to a history museum filled with dinosaur bones, exotic taxidermy, and most importantly, a space shuttle that briefly transports Ellie into an imaginary world where she can explore the stars.

It's a sequence filled with the kind of stuffed-to-the-gills level design and storytelling Naughty Dog is known for, minus the brutal combat and tense horror, but even big story beats have to start somewhere.

Old tools, new medium

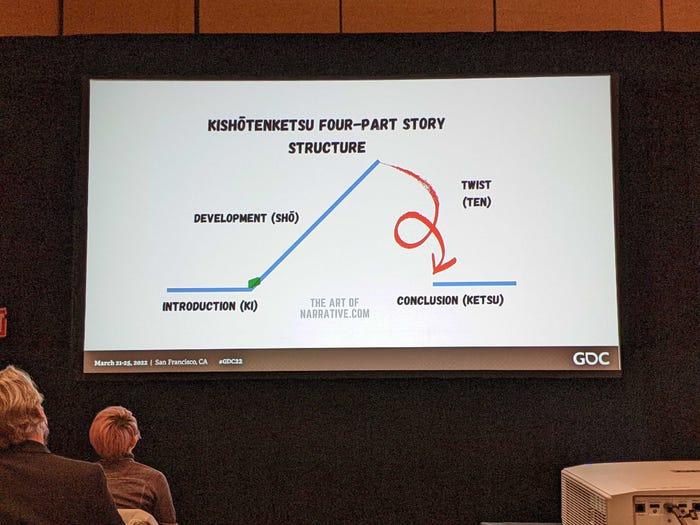

In classic Asian storytelling, writers often use the Kishōtenketsu (or "introduction, development, twist, conclusion") tool to chart the "anatomy of interesting events." It's a tool most players will recognize from the Mario series. In The Last of Us Part II, it helps set up moments both big and small and how players can interact (or miss) them.

"Even without challenging mechanics, we can give players tools to shape their experience," Hill said.

Hill wanted to reward players who wanted to linger and enable players who wanted to rush to the next beat. To do that, Hill used focal points: Unmissable parts of the experience, be it dialogue, story moments, or something else. Basically, if the story wouldn't work without it, add it to the list.

One moment Hill uses as an example of how improv-style storytelling impacted The Last of Us Part II's narrative is early on in the flashback. As an introduction, Joel and Ellie are venturing through the woods, all while Ellie continually asks Joel what he has in store for her big birthday surprise. There's your development.

Before Ellie can get a firm answer, Joel jokingly shoves her into a river. A classic twist, built upon further when Ellie gets her revenge and shoves Joel in later on. There's your conclusion for now.

Later on, when the pair finally reach the museum, Ellie turns a corner to witness a massive statue of a T-Rex. When Hill was showing off a rough 3D version of the level to a team lead, the first thing the lead asked was "can I ride that T-Rex?" Of course, the answer had to be "yes, and."

Hill notes that there are two kinds of players: The ones who want to charge through, and the ones who want to exhaust every optional activity before finally moving forward. Hill and other designers at Naughty Dog introduced one dinosaur skeleton to interact with in the museum lobby, then another in a hallway, before building to a large room full of skeletons on display.

So how do you find these moments? The simple answer is iteration. For The Last of Us Part II, the designers took more of a storyboard approach rather than scriptwriting.

Hill cites a particularly cartoonish storyboard from Knives Out as an inspiration, showing Ana de Armas' character surrounded by a throne of blades, but drawn as a crude batch of squiggly lines rather than professional artistry. Basically, don't worry if it still communicates the idea.

Hill and his fellow designers also literally acted out scenes together in an improv style, attempting to gauge the physicality and how naturally the dialogue felt when in the thick of it.

"The way we worked is we would have a short outline, and we would literally act it out as a strike team. When we get hit by a board, me or the leads would tumble onto the floor, crawl around. It's got to feel like this, just to see if the rhythms or emotions are valid. If we're able to sell it, maybe we can get the player invested. If I can't sell it even with my energy, maybe it's a bad beat."

Ultimately, Hill and fellow designers use these techniques to make anything feel possible, even in a linear space.

Read more about:

FeaturesAbout the Author

You May Also Like