What Star Wars: Squadrons can teach us about reviving classic genres

All wings report in.

In 2020, EA Motive sprung out of nowhere with Star Wars: Squadrons, a compact dogfighting simulator that followed the footsteps of Star Wars: TIE Fighter and Star Wars: X-Wing. Its release was notable not only because of how popular those games were in their heyday, but also for the fact that not many flight simulation titles have made it to market lately.

It's been such a long time since such games were mainstream that making a game like Squadrons might be considered an effort at genre revival. That made creative director Ian Frazier's GDC 2022 postmortem of the game's development all the more interesting. This wasn't just a look inside a successful Star Wars game, it also contained steps to consider when reviving classic genres.

Frazier's full talk tackled everything from snubfighter design to best practices for focus testing. Here's some highlights that exemplified what the game did so well.

Aphra-level archaeology

Frazier's talk began with some familiar patter about how the Squadrons team comprised of so many Star Wars fans (game developers, being fans of Star Wars? You don't say).

But that fandom came paired with development strategy. Frazier and his colleagues raided the archives for copies of the different Star Wars space sims from the '90s, rigged up some old joysticks, and had team members play them.

A key part of this effort was making sure that players both new and old, Star Wars fans and Star Wars fair-weather-fans, took a shot at these old games. The goal was to honestly assess what worked (and didn't work) about these old titles. Frazier said the team took it a step further, digging up old reviews and FAQs to read contemporary assessments about the flight simulator genre.

Frazier noted that the flight simulator genre had fallen out of favor in the commercial games market because their increasing complexity didn't appeal to as large an audience. It's a song we've heard over and over again—game development growing more expensive means developers need bigger audiences, and if there's a cap on the audience, it's hard to justify development costs.

Echoes of that conundrum would follow Frazier's story about Star Wars: Squadrons' development. EA and the team at Motive knew there'd be a balance to strike between raw fan appeal and accessibility, and came up with a great solution to identify what players would want out of the game.

While work on early prototypes proceeded, EA gathered a focus group of players who would participate in a "forced choice exercise." This wasn't just an act of sitting down players in a room and asking what they wanted. They actually used a kind of deckbuilding mechanic to help players prioritize what features they wanted in what contexts.

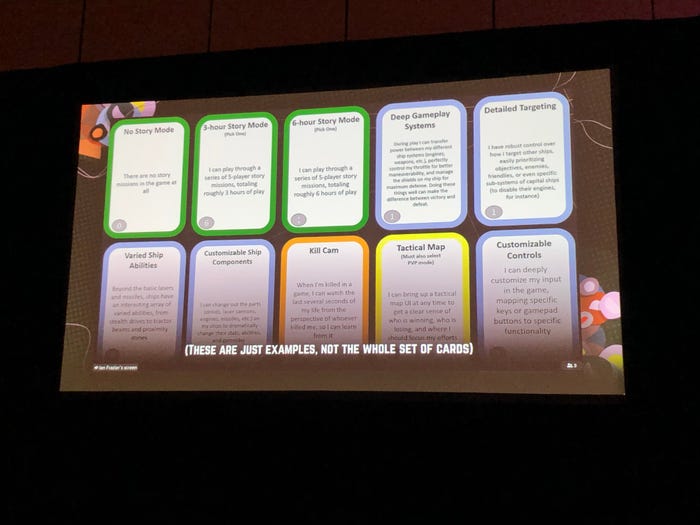

The cards Frazier shared in his talk were all color-coded to represent different categories. In the exercise, cards were given different values, and players were invited to build decks representing the game they'd want to play. Different focus groups would use different point values and budgets, adding a neat mix of creativity and interactivity to this process.

Frazier's samples of the forced choice exercise cards

(As one of our Twitter followers pointed out, it's an exercise that feels like those "you have $15, build your superhero team" memes of last year).

Frazier said that EA found this process so successful, it's expanded these forced choice exercises with the upcoming Dead Space remake, which is also being helmed by EA Motive.

Embodying the energy of Incom, Sienar, and Industrial Light and Magic

EA Motive spun up the first Squadrons prototype in 2017, using tech built by Criterion for the Battlefront reboot's flight modes. The first prototype shown looked shockingly close to the final game. A week after it was made, the team would also get it working in VR.

Support for VR headsets remained a priority for EA Motive, even though the team knew it was for a fraction of a fraction of the total userbase. As work on the game progressed, every feature implemented in the "2D" game had to also work in VR. This thinking would also lead to the support of HOTAS and HOSAS flight sticks on PC and console.

Nailing the "feel" of Squadrons meant reconciling a number of different priorities. The top-level guidance Frazier led with was that player ships had to be "powerful yet vulnerable." Speed would be a key sensation, even when ships like Y-Wings, TIE Bombers, B-Wings, etc. would all trundle along compared to the faster A-Wings and TIE Interceptors.

All of the games' ships would be designed to be hypercapable, but also fragile. "You can do amazing things, but it doesn't take a lot to take you out of action," Frazier said. As development began to align around a MOBA/hero shooter-inspired objective-focused game mode, this meant making sure all ships could play for combat or the objective, but could be blasted out of the sky in a heartbeat.

Power and vulnerability can be conveyed in more than raw statlines as well. Frazier said the team worked to engineer the sensation of being a fragile creature with only a thin layer of hull between you and the void of space. The player camera was anchored as the pilot's POV, meaning moving it around would look around the cockpit. A subtle bit of reverb was added to all of the players' voice lines, to make it sound like their voice echoed off the hull.

The cockpit of a T-65 X-Wing

Expanding outward, Frazier explained that the UI team engineering the cockpit controls worked with Lucasfilm Limited to both mirror depictions of the different consoles as seen in the films, and make sure they were readable for gameplay. "We were pretending Incom, making X-Wings, or Sienar Systems, making TIE Fighters," he said. "We also pretended to be Industrial Light and Magic working in 1977."

That meant using cathodes, metal plates, and material that all looked like they were stored in the back of a Van Nuys warehouse in the late '70s to answer questions that the fictional Star Wars engineers might be asking. Frazier called out that the computer screens in the different ships (even ones that weren't around for the first film) particularly embodied this philosophy.

If you play Squadrons in the highest resolution in VR, you can lean in and see the individual dots creating images in the interface. Similar details were applied elsewhere. Peer closely enough where the canopy and hull meet and you'll see scuffs in the paint that line up roughly with where a pilot would be repeatedly grabbing the hull to pull themselves in and out of the ship.

This immersive focus was flipped on its head when designing the hangar system. In both story and multiplayer modes, the hangar is where players can customize their ships' look and upgrades. Instead of an in-universe, diegetic interface, the Squadrons team made this a more menu-focused experience.

The team implemented a post-processing filter that would overlay ships while diving into menus, and didn't allow free movement in the hangar. Why? Free movement in the hangar "fought against the focus" of Squadrons, Frazier explained. It opened doors in players' minds about what might be in the different hangars, how explorable the capital ships might be.

Frazier described the decision to not develop down that path as being based in the core fantasy, but it's also not hard to imagine how expensive free roaming movement might have wound up being. He did say that when players finally encountered the hangar system, veterans of the '90s flight sim games described it as having an "old school feel." This wasn't fully intentional, but a nice bonus.

Better VR than the Star Wars Holiday Special

As mentioned above, Squadrons' VR development took place alongside the overall game development. This meant it wasn't added as a last-minute feature, but rather something that impacted the game's core development.

For instance, ship models for the game environment couldn't rely on normal maps, they had to be hand-modeled. This got especially challenging when creating the models for the several-kilometers-long capital ships.

Screen shake is a great tool for registering hits on a players' ship, but in VR that's a good path to making your players motion sick. EA Motive's solution was to keep the player camera view stable during impact, but have the cockpit shake around it.

And if you've played Squadrons in VR, you'll know that this development feature meant the team had to expand how much of the cockpits it modeled, showing areas of the ships that never appeared in the various films.

Frazier referred back to the partnership with Lucasfilm Limited, noting that they had to work closely with the Star Wars IP holder to nail these environments while making them gameplay-friendly. This apparently led to the team getting to look at concept art and photographs of different Star Wars ships that were never shown to the public.

One neat detail from this part of the process? While some iconic on-camera ships like the T-65 X-Wing had very visible control schemes that needed to be preserved, others like the TIE/ln didn't. Even across other forms of media, there wasn't a "canon" depiction of the standard TIE Fighter controls that the team could draw from.

That meant the partnership with Lucasfilm led to the creation of a unique (and very cool-looking) interface that mirrors what little of the controls is seen in the films with what works in Squadrons' gameplay.

The final TIE Fighter interface

Frazier couldn't share full numbers on how many Squadrons players experienced the game with VR headsets, but he did note that the percentage of VR users was much higher than any market research indicated.

"Expand your audience, don't replace it"

Frazier closed out his talk with a reflection on the process of making a niche game targeting players familiar with a niche drama. Looking at his overall talk, you can see echoes of the decisions EA Motive had to make to keep the game in scope for a title that probably wouldn't match the Battlefront series in terms of revenue.

A development process that wasn't anchored to the '90s flight sim genre likely would have chased that larger audience, possibly at the expense of those flight sim players. "We did need more players than just '90s flight sim fans," he admitted. But Motive wanted to expand the audience, not replace it.

You can see some of these compromises in the decision to include more modern game conventions, like a MOBA-flavored multiplayer mode and a campaign that's almost a full-length tutorial for the multiplayer. Frazier noted that a co-op mode for the campaign was cut because tossing wingmates into the story experience began to interfere with players' abilities to learn such complex systems.

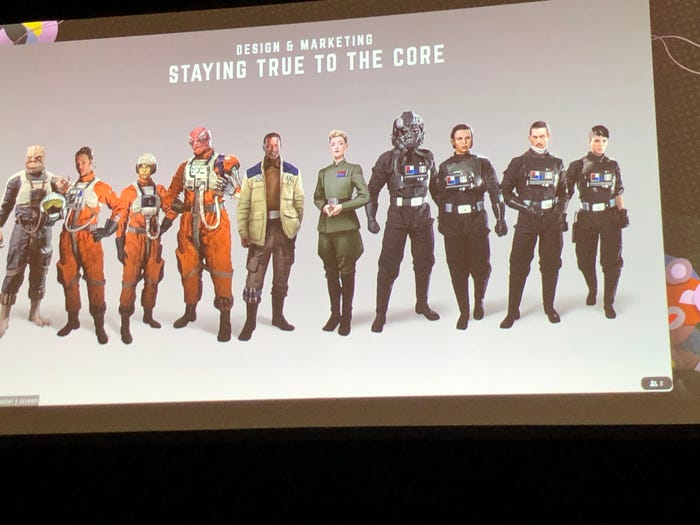

Frazier also nodded to the expanded push for improved accessibility and inclusiveness in such complex games. He didn't dive into full detail on some of the accessibility choices the team made, but called out the use of diverse characters in the story across both factions (and a very inclusive character creator) that helped more players feel represented in the game.

Squadrons' cast included characters of different races, genders, and sexualities

Looming over all of the incredible details in bringing Star Wars: Squadrons to life was the specter of compromise. It seems clear that in order to pitch the game to EA, Motive had to manage expectations and position market data as both an argument that a flight sim revival game could do well, but not "billions in revenue" well.

Working in those narrow confines meant every development decision—whether tilted toward the core fanbase or a less familar one—needed to be weighed carefully. "When we considered changes [to the game], we weighed them against the core fantasy," Frazier said.

It's an impressive feat to see that in an era of big games and big uses of IP, the team at Motive found a way to create not just a neat Star Wars game, but a revival of a genre that once dominated the world of PC game development.

Read more about:

FeaturesAbout the Author

You May Also Like