Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

"Despite featuring zombies and developing a game where the foreboding sense of danger never leaves you, we choose not to mimic the artistic direction of similar titles." - Gwenaël Massé, artist on Dead Cells.

The Gamasutra Deep Dives are an ongoing series that aim to shed light on how specific design, art, or technical features within a video game come to be, in order to show how seemingly simple, fundamental design decisions aren't really that simple at all.

Check out earlier installments, like this great Deep Dive on creating a new language forPlanet Coaster, or maintaining player tension levels in Nex Machina, and achieving seamless branching in Watch Dogs 2’s Invasion of Privacy missions.

If you're chiefly interested in Art Design Deep Dives, check out this great one on the hand-drawn art and animation of Jotun, and achieving seamless branching in Watch Dogs 2’s Invasion of Privacy missions.

Hello, my name is Gwenaël Massé, and with Thomas Vasseur, we're the two artists of the indie studio Motion Twin. Among others things, I’m tasked with designing the backgrounds of Dead Cells and I hope that sharing some insights on our production process may, somehow, help someone someday.

So, let’s get to it. We laid the foundations of the artistic direction of Dead Cells on three pillars: a saturated color palette, Celtic architecture and the theme of alchemy.

We chose to use highly saturated color spectrums for several reasons. The first would be the consistency between the gameplay and the art direction. Saturated backgrounds and characters really shine when it comes to keeping the player awake and alert, drawing the attention of the eye to any new element appearing on the screen.

This leads the player to have a better understanding of the action and consequently a faster reaction time when responding to potentially lethal threats. Which feels great for a game wanting to be as fast-paced as we want Dead Cells to be.

On a pragmatic level, we’re using as much vibrancy as we can, which means we focus almost exclusively on increasing the saturation of the midtones. Complementary palettes (composed of opposing colors) are great for giving a confined feeling to a space, which is why we use them a lot in the design of our interior levels. On the contrary, we put the emphasis on analogous colors for the outdoor levels as it allows for more nuances and depth in the landscape but, even there, we still use complementary palettes to highlight the difference between outdoor and indoor areas.

Complementary palette used on an indoor level (Toxic Sewers)

Complementary palette used on an indoor level (Toxic Sewers)

Analogous palette used on an outdoor level (Promenade of the Condemned)

Analogous palette used on an outdoor level (Promenade of the Condemned)

To keep the consistency between the Lore and the visuals, we apply this principle to each and every level. We always make sure to add some unsettling background elements, which might suddenly appear to the player paying attention to the background. We really like the contrast created when a peaceful, warm environment, somewhere you might even want to go on holidays, meets the gloomy tracks left by the abominations actually living here.

This idea can be seen applied from the very beginning of Dead Cells. In the first scene, the main character rises in a glow of warm light while the cadaver of fallen giant rests in the shadow of cold colors.

Starting scene of Dead Cells

Starting scene of Dead Cells

Despite featuring zombies and developing a game where the foreboding sense of danger never really leaves you, we choose not to mimic the artistic direction of similar titles. For instance, highly contrasted and low saturated palettes are heavily used in Salt and Sanctuary or the Souls series, creating quite a dramatic atmosphere.

Random beautiful screenshots found on the Internet

Random beautiful screenshots found on the Internet

While we understand the benefits of this design, we also wanted to add our modest contribution and new touch to the landscape of hardcore games. More specifically, we wanted to prove that a violent, cryptic ambiance, does not necessarily demand desaturated colors.

As such Dead Cells tries to ally the despair and feeling of fallen glory found in the remains of an ancient, triumphant, kingdom with a lighter tone, a colorful character and some strokes of humour. We wanted something that doesn't take itself too seriously. From an artist's perspective, saturation allow us to be graphically consistent with that desire. Flashes of brilliant sunlight juxtaposed against grim dungeons and falling towers, a beautiful forest and dappled light contrasted with bloodied traps and items of torture.

Of course the art direction also had to stand out from the crowd of comparable games. We wanted to say something like; “we can do difficult, we can do frustration, we can do that feeling of achievement when you beat a particularly difficult boss”, even though it’s happening in a strangely vibrant colourful world.

The underlying practical reason remains the fact that the contrast in colour pallets really just helps the readability of the game. Threats stand out and your reaction times are naturally better when you can clearly see what’s trying to kill you.

Lastly, when you start a project like Dead Cells you hope that you’ll be done in a year and a half, in and out, but you know, somewhere in the back of your mind, that this game is going to be your world, your day job, your after hours, you conversations for years to come… So you want to build somewhere that you’re happy to hang out for a long time!

The events in Dead Cells take place on an Island inspired by Skye Island in Scotland, particularly the architecture from the X to XIII centuries. Mainly influenced by Celtic Christianity, we chose this architecture as a reference to the cold and harsh nature of its old buildings as well as for other iconic features of this style, notably its basalt columns.

We tried to reproduce the troubling atmosphere established by these elements in Dead Cells, again, with the same idea of reminding the player of the hazardous world that their exploring. The more organic details of this architecture then serve as a link between this bleak setting and the occult side of Dead Cells’ lore: alchemy.

One of the photos used as a reference for the Island of Dead Cells

One of the photos used as a reference for the Island of Dead Cells

Basalt columns which inspired a concept art for Dead Cells

Basalt columns which inspired a concept art for Dead Cells

You can see more photos used as references for the game here, if that’s your thing.

You can see more photos used as references for the game here, if that’s your thing.

This third pillar ties the whole thing together, the Lore and background, monsters, gameplay, biomes, etc. For instance, the Collector belongs to the magical aspect of Dead Cells and is a key element of the meta progression system, allowing the player to infer a little more about the world.

A very pronounced graphic charter, relying heavily on specific materials like copper, glass and magical runes allows us to convey the alchemic nature of the world to the player at the same time as drawing a clear distinction between the background and crucial gameplay elements (power upgrade, teleporter, chest, etc.).

These three leitmotifs form the foundation of the art direction of Dead Cells. On top of that, several rules tied to gameplay and technical limitations (legibility of the action, level design, camera, etc.) are then added over the base with the same old goal in mind: ensuring the consistency between the levels and a fluidity to the eye of the player.

The fast-paced orientation of Dead Cells requires giving the player the opportunity and the ability to react quickly, failing which, the game would seem unfair and frustrating. To help the player “read” the screen easily, the visuals have to reflect the degree of importance of each information.

Our first concern is to properly indicate the possible ways of progressing to the player. In order to do that, the background of the levels and the collisions have to contrast as much as possible, while the colors used to design the background have to fade into each other, creating no discernible rupture.

After the collisions, the second thing the player must see is the various gameplay elements with which he may interact: ladders, platforms, etc. These have a degree of contrast somewhere between the backgrounds and the obstacles.

Finally, we need to make the player understand the potential threats, even if it’s an unconscious realisation. The enemies, their projectiles and any spells they may eventually cast are treated with high levels of saturation, contrast and brightness so the immediate danger is quickly identifiable.

Some gameplay components are found in each levels, so they have to be recognisable by the player each time one of them appear on the screen, no matter the specific graphic charter of the level or if it’s an indoor or outdoor one.

To this end, we designed a specific visual language similar for all these gameplay components.

Comparison between the fountain of youth and an elite’s grave.

Comparison between the fountain of youth and an elite’s grave.

The structure here is fairly identical, with the gameplay element located at the center of vertical flags, and a circular stone symbol behind. As always, the main point of interest of the scene (the fountain and the grave in this case) stand out with a more pronounced shape and a higher level of brightness.

If the levels are procedurally generated, it’s not the case of the world itself: the sequence of the levels is hand designed and carefully thought out. It allows us to link the biomes in an immersive and believable way, ensuring that the player never has a “that makes no sense” moment. For example descending into the depths of the sewers in order to arrive at the ramparts (the top of the castle) without a logical transition would make no sense.

To counter this issue, we added a mandatory elevator before you access the ramparts, as well as a long tunnel before the sewers, this visually signals direction and location to the players.

The exit to the ramparts is always preceded by a lift

The exit to the ramparts is always preceded by a lift

As I mentioned before, we tried to make the differences between an indoor and an outdoor level as striking as we could. We think it adds to the visual richness as well as the feeling of a more credible, complex world. Beside, the feeling off bursting out of a darkened room into blinding sunlight is always nice.

To trick the eye and add depth to the landscapes, the main tool is using analogous color palettes. We also rely heavily on parallax textures, particle effects giving more density to the air, clouds placed in the foreground, etc.

Concept art for the graveyard

Concept art for the graveyard

Interior decoration

One of the main issue we had with designing the decoration of Dead Cells’ levels comes from the procedural generation we use to build them. To ensure consistency inside a biome and to maintain realistic placement of decorative items (doors, alcoves, torches, etc.) in spite of the randomness created by procedurally generated levels, we begin by dividing the background into sections of variable sizes. Each element of decoration has a specific set of rules applied to it: for instance, torches have to be located near an alcove or a door.

Each color represent a different type of section.

Each color represent a different type of section.

Color palettes and gradient maps

The workflow we went with is thought out to save us time when we inevitably change our minds about which direction is best for the game. First we draw the textures of the parallax in the background with grayscale colors before applying a gradient map. Modifying the gradient map is then all we need to do in order to change the color palette of a biome.

Texture for the trees in the background

Texture for the trees in the background

Gradient maps

Gradient maps

This has proven to be quite useful on several occasions, for example; we can have variations of the same levels, or we can rework a biome if needed. The promenade’s biome was originally orangey and reminiscent of fire, which became an issue when we decided to switch the place of this level with the one just before the ramparts for gameplay purposes. We found the two biomes visually too close to be be next to each other...

First version of the Promenade of the Condemned The Ramparts

But, thanks to our workflow, we were easily able to change the gradient map and voila, it’s a completely different feel.

Second version for the Promenade of the condemned

Second version for the Promenade of the condemned

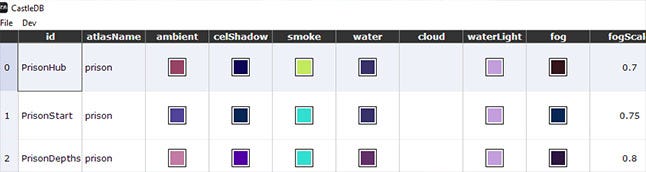

Obviously, we’re using heaps of others variables to polish the ambiance of each level: color of the lighting and shaders, smoke, water, mist, vegetation density, etc.

Our little homemade tool to tune the variables

Normal Maps

Fun fact: Motion Twin is probably one of the only videogame studios to draw our normal maps… by hand. Roughly, a normal map is a second texture applied to the base texture to adjust how the elements will react to lights (be it the light from a torch, a spell, etc.). usually, normal maps are generated in 3D software or through some specific Photoshop plug-ins. However, every plug-in we tried was a bit of let down, often rendering something a bit too flat, blurry or with an emboss effect similar to a coin. Not really what we were looking for.

This led us to draw the normal maps by ourselves directly into Photoshop. Indeed it costs us some weekends and big cups of coffee, but we feel it’s worth it to get a custom super satisfying result. It let us play easily with the volumes, quickly put the emphasis on some parts of an object and we can improve the legibility of a background by tweaking the opacity parameters of the various layers.

This is how a texture of Dead Cells looks like in Photoshop.

This is how a texture of Dead Cells looks like in Photoshop.

The backgrounds of Dead Cells started out with a few simple ideas. The ancient, enduring shores and architecture of the Scottish island Skye and our own interpretation of an alchemic bestiary, splashed with luminescent colours and given life through attention to detail. All of this underpinned by a workflow designed to minimise the cost of retakes, while allowing for fine control of colour palettes and lighting effects and topped of with a decent dose of iterating over everything.

Overall I think the process we used and the direction that we took allowed for a lot of flexibility and really helped us add and modify levels quickly and easily. It’s definitely allowed us to achieve that “retro-modern” feel; pixel art style and “square” looking level design contributing to the old school feel on one hand. While on the other; heavy saturation, dynamic particles, normal maps and 3D lighting give us the contemporary touch.

In the end I think it’s worth noting that we were always walking the line between the temptation to really go for it with effects, dramatic scenery and having a great time as artists and the demands of the gameplay. While we may have made some compromises for dramatic effect here and there, we’ve tried to stick to the guiding principles that we laid down at the beginning and honed throughout production.

I hope this little article might have interested you or helped out in some small way. Of course if you have any questions or something is not quite clear, feel free to spam Thomas or myself on Twitter.

Cheers!

You May Also Like