Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Robotron and Defender creator Eugene Jarvis needs little introduction, as one of video gaming's arcade pioneers - and in this in-depth interview, he discusses the future of the arcade medium, controversy over Target: Terror, and the XBLA legacy of his twitch game trailblazing.

Eugene Jarvis needs little introduction. As the creator of Defender, Robotron (and accompanying two-joystick control system), NARC, and the Cruis'n series, his reach in gaming, especially as concerns arcades, is incredibly wide. Even if you've never been inside an arcade, his influence can be felt in the glut of indie and downloadable games using the Robotron control scheme, such as Geometry Wars and Blast Factor.

More recently, Jarvis has returned to the arcade scene with his company Raw Thrills, whose first game was the very controversial light gun shooter Target: Terror. The game was very inflammatory at the time, and while part of it was simply an eyecatch, there's something to be said for putting a game out there that makes people consider actions and ramifications, if indeed it does.

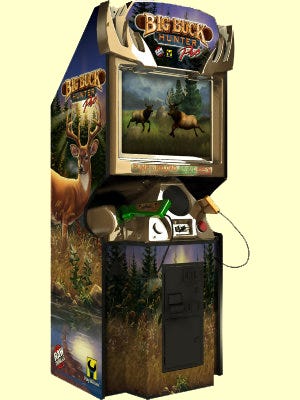

The company's newest game is The Fast and the Furious Drift, and on the occasion of its release to arcades, we spoke with the industry legend at length. Jarvis gives us a very realistic portrait of the current arcade industry, where rising costs and waning consumer interest compete. This difficult scenario encouraged a recent merger between Raw Thrills and Play Mechanix (Big Buck Hunter), which allows sharing of technology and ideas, as well as multi-team workflow.

In this interview, we discuss the changing methods of designing for arcade games, how the Wii is (or isn't) encroaching on the unique experience of the arcade, to what extent graphics still matter, why most modern arcade cabinets are basically just dedicated PCs, whether Target: Terror was a political statement, and how far the envelope can be pushed.

How different is the arcade industry now, versus its heyday?

How different is the arcade industry now, versus its heyday?

Eugene Jarvis: In some ways, it's similar to where it was in the late '70s, before it became huge. It's half show and half garage sale. It's on a smaller scale, but the challenge is still there. Trying to create a game that players care enough to pop a buck into every two or three minutes is a high bar. In the case of something like World of Warcraft, there may be 20 million people playing it, but they're not paying a buck every minute to play that game. They're paying a buck every ten hours. It's a different animal.

How do you design arcade games so that they eat dollars now, instead of quarters?

EJ: If you could tell me, you'd have a job! You have to pack a huge amount of entertainment into a small stretch of time. It's like an iPod versus Microsoft Windows. It's got to be so easy to start the game, and be very clear as to what you're doing, and have a super elegant user interface. The action has got to hit you in the face.

A lot of people associate that kind of entertainment with casual games, but you're coming at it from a more hardcore angle. They're certainly easy to get into, but the games themselves are a bit more hardcore.

EJ: There's really two huge groups of players in the arcade market. One is the group that just really wants to have some fun and go to the arcade every six months, and then there's the dedicated group of players that pump a huge portion of money into the games. You have to have some depth to the game, and have challenges beyond what the average casual player would notice.

Most of your games are getting sold to movie theatres and bars and things like that, right?

EJ: Yeah. I guess they call it the "street" market. It includes movie theatres, bars, bowling alleys, pizza parlors, Wal-Marts, and other places. There are arcades, but they're much bigger these days, like Gameworks, Dave & Busters, and Chuck E Cheese's. They're a big place with probably several hundred games, and that's more of the classic arcade environment.

Until you guys, along with Play Mechanix and Incredible Technologies came along, there weren't actually new games coming out for a number of years with any regularity.

EJ: There were new releases, it's just that the games weren't selling that much. The reason was that it was a changing marketplace. Back in the '90s it was all about fighting games like Street Fighter and Mortal Kombat. Back in the '80s it was all about character games like Pac-Man and shooters like Defender, Asteroids, and Space Invaders.

Those genres hit huge, then waned in popularity. You have to follow the curve and see where the players are. You have to give them today's game, which is more of an environmental thing. You have gun-based interfaces, or driving games with steering wheels, gas pedals, and gear shifters. We have a motorcycle game called Super Bikes, and you're leaning the motorcycle. It's much more physical and control-intensive. It's play that you can't get at home. People are still going to play their Xbox or PlayStation 37 hours a week, so we have to give them something that is not on their PS3 or their Wii.

The Wii is rapidly encroaching on that area, because you can have a steering wheel or gun as control input, theoretically.

EJ: Well, I think there's a big gap between a theoretical steering wheel and a real steering wheel. You're air-steering!

The games you've released so far have been within existing ideas of what those cabinets can be. Do you envision new types coming up, or is that not necessarily important?

EJ: It's very important to keep evolving. When you're a startup company, the first things you do are to try and hit the big targets that have historically sold well, and that you think you can do a better job of. We started out with driving and shooting games, then we moved to the motorcycle. The next thing we're going to go into are boat games and skateboarding games.

We're stretching the interface, and trying different types of simulators. I hope to get into the VR space, with headset games, in the not-too-distant future. The technology there is finally getting to the point where it's beyond the hype phase. In the early '90s, everyone was hyping it, but unfortunately all it did was give you a headache at three frames a second. Now, the technology is getting to the point where you can provide a high-quality experience to the player. We want to go into some of those more immersive areas.

What made you decide to get back into this market, and how did you end up forming Raw Thrills?

EJ: The whole thing was kind of a mistake! Midway was closing down, and they decided to focus on the home market. The arcade space is a smaller, niche market these days, and it didn't make sense for such a large corporation [to pursue it].

So anyway, one of the guys from Midway asked me, "Hey Jarvis, why don't you start a new arcade company?" Somehow, they talked me into it, and here we are. We're doing very well. We just got the manufacturer of the year award from the AAMA. For a small company, it's a good opportunity. It's a small market, but you can really focus on that marketplace and design games that appeal to players. You also have to be very competitive on your pricing.

Most of the Raw Thrills guys were from the Midway arcade side?

EJ: That's right. We had a couple of guys from Microsoft and a few other companies, but mostly it was ex-Midway guys.

When you sell arcade games, do you actually get returns on the coin drop, or is it only selling the cabinets?

When you sell arcade games, do you actually get returns on the coin drop, or is it only selling the cabinets?

EJ: Traditionally, we just sell them the game, and you don't see the coin drop. Incredible Technologies -- the Golden Tee Golf company -- have an evolved business model where they are actually participating in the coin drop. I wish I could! You look at some of these games, and in three or four years, they'll make like $15,000. You just go, "Shit, where's my money?" But if some competitors are just going to sell them the game, then you'd better too. Traditionally, that's been the model. You just sell them the game. My goal is to have a game good enough that I can participate in the coin drop, but you need to have a phenomenal game in order to do that.

Who are your true competitors right now?

EJ: There's Sega, which is a very strong competitor. It's amazing how many games they release per year. They're very strong in Japan, and are a very strong competitor domestically. There's Namco, who are most famous for Pac-Man. They're still making Pac-Man in the year 2007, if you can believe it. Their biggest seller in arcades last year was [Ms.] Pac-Man and Galaga. They're very strong with their Time Crisis games, and their Wangan Midnight driving series.

There's a company called Global VR on the west coast who do the EA games like Need for Speed and Madden in the arcade. They also do a golf game with EA. They're another very strong competitor in the space, along with Incredible Technologies with Golden Tee Golf. There's some competition out there, but it's not with hundreds of companies. It's maybe ten companies out there.

What is your average budget for an arcade game compared to console space?

EJ: Our budget ranges from two to four million dollars typically for an arcade game.

Is that just software development, or does that include anything else?

EJ: That includes software, hardware, special interface boards, mechanical engineering for controls, and even the plastic mold. People want to see a new-looking game, so you have to put new plastic mold on where you sit and on the control panels. It's kind of a style-conscious business. Some percentage of it is, "Does it look cool? Do I want to sit on this motorcycle? If it looks stupid, I'm not even going to want to sit on it." You've got to make it look cool. There's a lot of 3D CAD modeling, to create these different molds.

How do you do in Japan? You're distributed over there, right?

EJ: Taito is our distributor in Japan. They're another competitor for us. They do Battle Gear, the driving series. They've been distributing us in Japan for the last few years. We've done pretty well. It's not our hugest market. Two or three percent of our business might be in Japan.

So most of it is here, or in Europe?

EJ: We're much bigger in Europe [than in Japan]. We probably do 20 percent of our business in Europe. It's interesting, because there is a cultural [divide]. Americans design different games than Japanese designers. It seems like American games historically have done better in Europe. Japan has a big cultural divide there.

Microsoft is always trying to figure out how to sell their Xbox in Japan. It's a very specialized market. They do their own thing, and it's been hard for American designers to get into the Japanese market. We've actually had more success in China and some of the other Asian countries like Korea. They seem to be more receptive to American games.

So the U.S. is about 60 percent or something?

EJ: Yeah, the U.S. is probably about 60 to 70 percent. That would include Canada. It's a worldwide business. Russia is a big growth area. India is a very big growing market right now. It's kind of fascinating, how it's a worldwide business.

How do you sell new games to reluctant arcade operators?

EJ: It's a tough racket. These days, it's more of a replacement business. In the golden era of the '80s, you were just filling up locations with games, and it was much easier to sell. Now, your new game has to make a lot more money than the game it's replacing. They've already paid for the old game many years ago, and they're looking at putting out a lot of money to buy a new game. They're worried about whether the game will bomb a year or two years from now, or even six months from now. If they lay out seven or eight thousand dollars for a new game, and the thing bombs, [that's a problem]. They're not a charity. They want to make money!

It's a tough sell, and you really have to pack as much as you can in the game. We just issued a new game in our The Fast and the Furious series called The Fast and the Furious Drift. We put 18 tracks in this game. There must be six or seven shortcuts on each track. The amount of material there is just huge, and you do that to make the game last a long time on location. If the players get tired of your game in three or four months, nobody's going to buy your game. There's a huge push to pack more things in there. It's a little bit similar to the death spiral in console games, where you have to throw in more and more material, and the budgets haven't been increasing to pay for all that material. The market has not really been growing that much. The market is like stealing food from somebody else.

So budgets are actually going up still?

EJ: Absolutely. The problem is that there is no market for a low budget game. You can make one, but people will just laugh at it. They won't play it.

Do graphics actually matter in arcade games now? It may matter from the operator's side, but does it matter from the player's side?

EJ: Oh, absolutely. In video games, if it's about gameplay, it's about graphics. One without the other is going to be a failure. If you have the best graphics in the world but no gameplay, it's going to fail. If you have the best gameplay but everything is a square box, nobody is going to play it. It's a marriage of the two. You try to do the best you can within your budget to make the game look as good as you can. It's hard to have the same graphic quality of a $30 million game.

If you look at our games versus the Need for Speed series, their graphics are probably better, but they only have one car on the screen for most of the game. We tweak our game. We may not put as much power on the backgrounds, but we tweak our game so we can have nine or ten cars on-screen racing. You just get a lot more gameplay out of it. In some ways, the console games can be more of a solitary experience.

One car looks really great, but when two cars come on the screen, the framerate drops. It's such a rare occurence that players don't care as much. But in an arcade game, you've only got two or three minutes to impress, and if you start dropping your framerate to 20 or 30, nobody's going to want to play your game again. It's got to be very responsive. We're biased more toward gameplay and more action on the screen, as opposed to dazzling with backgrounds.

The Fast and the Furious (Photo Credit: http://wayoftherodent.com)

What architecture are you using?

EJ: We use PCs, mostly. The PC is just such a powerful machine, especially with today's graphics cards. We also have some custom ports to drive the IO, like the force feedback steering, to manage the lean of the motorcycle. We have some custom boards for that sort of thing. For graphics, though, you really can't beat a state-of-the-art PC system.

I thought you were using Atomiswave at one point. Is that true?

EJ: No, never. Sega had used that for many years, as did Sammy. It's a Dreamcast-derived hardware. There was also the Chihiro system, and before that there was the PlayStation-based System 22. The PC is a much more flexible platform. If you need more power, you just throw on a better graphics board.

Have you looked at Taito's Type X? That's basically a PC.

EJ: Yeah, it's officially a PC, so it's just kind of a name. I think the Lindbergh is just a PC with a fancy name. Everyone has to have a fancy name, but you pull off the cover and look inside and it's just a freaking PC!

Do you feel like the age of arcades is returning?

EJ: I would have to disagree. Being in the trenches myself, I'd have to say that it's like cannibalism. You're just fighting to survive for the next day. It's a fun business for game designers because you can work on a smaller team and have more freedom and have more impact on a game, but it's a very rough market. The toughest thing is that when you're selling a CD for an Xbox for $70, that CD costs about 47 cents. There's some profit margin there.

When you're making an arcade game, you're selling it for $5,000-$6,000, and the thing might cost 80% of that [to produce]. Your profit margin is a much lower percentage, and from that you have to pay all of your costs and everything. It's a tough business. You really have to know what you're doing and it's a constant struggle between creating a game that can appeal to a player while working with a low budget, so you really can't make mistakes.

Are licenses important to that at all?

EJ: I think so. I don't think it's as important in the arcade area. In the console space, it's almost do or die these days. It's either a license or a sequel. It seems like only five or ten percent of new releases are new IP, probably. The average marketing cost to get people aware of your game is so high that you have to end up going with a license or a sequel.

In the arcade space, it is important to get peoples' attention on a game. The Fast and the Furious has been an amazing license for us. You've got attention. The problem in the arcade space is that if a game's a buck or 50 cents or whatever, that's all you get. The guy sees your license and puts in his money, but if the game stinks, he's not going to be back, so all you're left with is 50 cents or a buck.

In the console space, if you're hyping up the latest Harry Potter game or whatever and it turns out to be a stinker, maybe two million guys bought it anyway. They put it in their computer and found out that it sucks, but maybe they're too lazy to return it or whatever. The company still makes 100 million dollars, even though the game stunk, because it had a great license. In the arcade, you're going to get the guy's fifty cents, and he's gone. Gameplay is more important. Look at Need for Speed, which I guess is the number one game forever. In the arcade, it was only marginally successful. The Fast and the Furious destroyed it. It was really about gameplay and entertainment. The license was important, but at the end of the day, you really have to provide a fun experience.

How long do you think it's going to be until the arcade is no longer viable?

EJ: I wouldn't be in this business if I believed that! I think it's like a jukebox. We can all play CDs at home and we all have iPods, but at a bar, there's still a jukebox. I think when you're waiting for your pizza, you're going to want a fun arcade game to play, and when you're sitting at a bar drinking beers and want to kick ass on your buddies, you'll play Big Buck Hunter. It's about being at other places, not being at home.

When you're at another place, it's something fun to do, and you have all the environmental aspects. You've got a gun, a steering wheel, force feedback, or a motion cabinet. These things are very hard to do in the home environment, and I think the arcade still has that working for it. I think it will always be a part of the entertainment spectrum. You've got radio, TV, the Internet, and books, and they always continue to exist in their area even as technology goes on to create other platforms.

How big is the company? Do you have to have a separate R&D department?

EJ: We have about 50 employees, and two studios. We have the Raw Thrills studio, and last year we merged with the Play Mechanix studio. Play Mechanix has their own studio and facility. Their focus is the Big Buck Hunter series, and they've been doing other stuff lately. They've done a game based on Deal or No Deal. It's a fun arcade piece. We have those two different studios, and we're having a lot of fun.

Do you have to have separate people working on the hardware stuff?

EJ: Yeah. We've got a dedicated hardware department. The PC is a wonderfully flexible platform, but you have to have a full-time hardware department to keep up. The lifetime of a graphics board is like three days. You can design your whole game around this great new graphics board, and two weeks later, you can't even buy it. There's a whole new one, and of course your game doesn't work with that one.

You constantly have to re-engineer your drivers and your graphics to adapt to the latest PC technology because it keeps evolving and evolving. You really have to be on top of that, with the latest versions of Windows embedded, and if you're using Linux, you have to be up on all the latest Linux drivers and releases. It's amazingly challenging to make a production line run with things constantly changing underneath you.

I heard that you and your Play Mechanix cohorts are working on some kind of new online platform. Can you talk about that?

EJ: Yes! We're trying to bring the online tournament experience to the Big Buck Hunter franchise. It's a very competitive game, and players around the country are itching to prove that they can bring down more bucks than the next guy. It's a big push to get us into that online tournament space. The Play Mechanix guys have been in existence longer than Raw Thrills, and Big Buck Hunter was one of their first games back in the late '90s. They've been constantly improving that game, and it keeps getting better and better.

Didn't Sega release that for a while?

EJ: Sega did a competitive game called Extreme Hunting on the Atomiswave. They've got Extreme Hunting 2 out now. They're the big competitor with Buck Hunter. Buck Hunter was originally released by Incredible Technologies. Buck Hunter Pro is steps ahead of what came before. The designers did an amazing job.

How do you feel about so many indie games like Xbox Live Arcade games basically being Robotron clones at this point?

EJ: As they say, imitation is the height of flattery! The Robotron play mechanic -- with independent firing and motion -- is such a natural mechanic, and it has become a standard in the industry in the last 25 years. It's ideal for an arcade-type scenario on Xbox Live. The gameplay on games like Geometry Wars is just wonderful. Guys are just taking it miles ahead where we were at with Robotron, and I think it's fabulous.

Arcade classic Robotron pioneered the two-joystick control system

Have you considered entering that space at all?

EJ: We have, and it's something we've been tossing around and would like to get involved in. We've just been so booked up on doing real arcade games that we haven't had the chance yet, but we hope that maybe some day we'll have some of our arcade releases show up on Xbox Live.

The budget would be even smaller in Live Arcade than in real arcades, so it would be interesting to see the parallel there.

EJ: Yeah! If you look at a lot of the guys doing casual games today, there's some great stuff going on out there. It's a golden age to be a player, because the variety of games is just tremendous. There's a countless amount of titles. Anybody can throw up a website and have a downloadable game. It's amazing, man! I wish I didn't have a job! I'd get to spend more time playing games.

Do you actually play many games now?

EJ: One thing that I play a lot is the Age of Empires series. That got me hooked. Recently, I got my 360 and have been playing Gears of War, and that's pretty crazy. There's some funny stuff on the Internet, too. My son is 14, and it's funny to see the stuff he gets into too. He was into Club Penguin for awhile. It's amazing that there's so many nutty, nutty games on the Internet now. Miniclip has some interesting stuff going on now, along with all the other casual gaming sites.

What is your actual role in the games that are made at Raw Thrills? Do you do any actual design work anymore, or do you oversee everyone?

EJ: I'm kind of the guy who tastes the food in the kitchen. I'll create a two or three page design spec, and the guys are so creative that I'll just let them run wild with what they want to do with the game. It's really stifling to creativity when a company comes down with a 300-page description of every screen of the game, and everything's going to happen before anyone's played a single level.

There's a feedback process where you want to see what works and what doesn't work, and the design may move toward a different direction than what you intended. We give our guys a lot of latitude. We start with a two or three page description of the game, and then they'll just run with it. We try to get the game up and playable within a couple of months, because you just want to be playing that game constantly, to refine the gameplay and make it a lot of fun.

So you do a lot of prototyping and iteration, then?

So you do a lot of prototyping and iteration, then?

EJ: Yes. It's more of an iterative process. There's this new buzzword out: Scrum. It sounds a lot like what we do. The idea is to have short goals. Implement the goal, play the game, get feedback, then go to the next level. Say you're designing a driving game and you're designing 27 tracks.

Now, if you're a console company, you really are prisoner to your one-year deadline. They pretty much have to decide everything they have to do up front, and then just do it. If it turns out that it wasn't a good idea, then so be it. Hopefully, it was a good license. In our situation, we have a little more time. We'll run a two year project, and spend the first six months trying to get one level or one track to be where we want it to be. We hone that one, tweak it in, and get the car handling and the trick system. Then, once you've got that, you can design the other 15 or 20 levels and know that it's going to be a good game, because you've been playing it all along. The longer development cycle helps you do that. It helps you emphasize the gameplay, as opposed to having everything defined up front and hoping that you're right.

How many games do you have to release yearly in order to maintain success?

EJ: Just to keep the company going?

Yeah.

EJ: I guess we've done maybe one or two games a year. We're a very small company, so that can work for us. Obviously, if the company got bigger, we'd probably have to release two or three games a year. You've got to make sure they're good. The other thing you've got to do is realize that we're all human, and some games just stink. You've got to kill the stinkers, and you've got to stamp out those nasty, slow-death games. You've got to kill them before you use too much budget, otherwise it can sink your company. You've got to be vigilant, because some ideas are just not good. There's always that tendency to keep fixing them and fixing them, but some things are just not going to go. There's inherently flawed design concepts. The real challenge is to know when to just kill a project.

Have you had anything like that recently?

EJ: I would say probably about half the projects we do end up getting killed, because you realize that some point on the way, it's just not going to make it.

So are you generally the chief originator of those ideas?

EJ: On the Raw Thrills side, I've been doing a lot of the original designs. At Play Mechanix, it's George [Petro] and his designers. We have to bring on more guys and get some more ideas going.

It's interesting, because both seem to be designer-lead studios.

EJ: Yeah, but you have to stand back and let some of the new kids go with their ideas. Otherwise, you can get a little fossilized. That's a challenge. Me, I've been at it for 30 years. You don't want every game looking like Pong. You have to give some of the new guys the reign to kick out some new ideas.

Speaking of the fossilized type, you've worked with Jeff Minter on Defender 2000, right?

Speaking of the fossilized type, you've worked with Jeff Minter on Defender 2000, right?

EJ: Yeah. You know, Jeff also did Llamatron, a version of Robotron. He's an amazing guy. I guess he's doing stuff with Xbox Live Arcade now?

Yeah, he's got a game coming out called Space Giraffe.

EJ: That's guy's great. He's got to be one of the most creative guys in the industry, and I hope that he hits it big.

How do you feel about the way the game violence debate is going now? I know you've had some thoughts on that in the past.

EJ: It's funny, because we've kind of been off the radar. I haven't heard, but with the tragedy in Virginia, I'm sure that guy played video games...

They tried that angle straight off, actually. They said that he played Counter-Strike in high school and that meant something.

EJ: The problem is that every kid has played video games, so that's pretty irrelevant. The issue was much more at the forefront a few years ago. Part of it is that extreme violence is kind of like pornography. The first times you see it, you go, "Wow, that's pretty hot." Then the 37th time a guy gets his head blown off and blows blood all over the screen, [it just doesn't have that same impact]. We've seen it. We've been there.

It's more about gameplay now. If you have violence, your challenge is working it into the gameplay, and not just splattering blood all over the screen every two seconds. It's about how to make it more artful, more theatrical, and more suspenseful. I think we're maturing as an industry, and I think that's cool.

Was Target: Terror in any way a political statement?

Was Target: Terror in any way a political statement?

EJ: No comment!

That's cheating!

We were just having fun. At the time, there was quite a bit of hysteria. I think there were mayors of small Midwestern towns saying, "I need security! What if the terrorists attack? I need an FBI armored car at all times!" I think Target: Terror was going off that kind of hysteria, with what would be the worst case scenario. I remember there was a controversy with 300 guards on the Golden Gate Bridge…

So it was a bit of a social commentary on the hysteria of the time, but sadly, who would've envisioned the 9/11 attacks? That was the worst-case scenario, something even a paranoid schizophrenic couldn't envision, and it actually happened.

When you designed the plane bit…

EJ: This was all after 9/11, so the plane was actually inspired by the one that went down. To me, it's got to be one of the most gripping dramas ever, what happened on that plane. We'll never really know what did happen there, but it's an amazing scenario for an action game.

Would you say it's a semi-ironic look at it? Whenever I look at it, I can't tell if the vision is ironic or reactionary.

EJ: That's the beauty of it, I think. It's whatever you want it to be!

I think that it would be interesting to do topical arcade games like that regularly. It'll be interesting as social commentary and also as a money-making tactic.

EJ: I would like to see more of that. The last game that I did in that vein was NARC, back in the 1980s. I expected to see a lot more of those social commentary-styled games, along with satires and political cartoon-type games. It's amazing how little we've seen in that space. I don't know, maybe video game designers take themselves too seriously.

I wonder if the idea is as thought-provoking if it's open to interpretation, and it's not clear what your goal is, as in Target Terror.

clear what your goal is, as in Target Terror.

EJ: I think it is. I think the open-endedness really helps. You put your own meaning on it, and different people take away different things. There's more discussion, and there's more debate. If you're preachy, what's the fun in that? You want to have the latitude to play games from different angles and come away with different ideas. That gives the game a lot of staying power.

Was that actually intended with Target Terror?

EJ: That was our first game, so we just wanted to do the most outrageous thing we could think of, to get people to notice. There's so many demands on peoples' time that just to get noticed in the media for a new creative title is really tough. It helps to be the most outrageous you can.

You guys should get back to that.

EJ: We should, man. Maybe if we fuck up a few games, we'll get desperate enough to do something like that again!

Well, it seems like a good thing. The game sold, right?

EJ: Yeah, it was a good seller. We have some great designs for a sequel to Target Terror. We want to take it into Las Vegas and have some crazy stuff going on.

Do you find that people know you more for your legacy stuff than for your current work?

EJ: You know, I think so.

Does that bother you?

EJ: It's funny. As people get older, they always think of the games of their youth. It's kind of like the songs of your youth. The whole video game thing was new in the '80s. It was like the birth of rock'n roll, or the birth of cable TV. It was a big deal, and it made such a huge impression. Some of the newer kids who are a fan of the Cruis'n games I did at Midway, or The Fast and the Furious, Target Terror, or Big Buck Hunter, will remember those games. It's like a generational thing. You remember the games from your youth. A young kid who is into The Fast and the Furious might not have even heard of Defender. It's just like, "Whatever."

Some of us are snobbish and don't approve of people not having heard of Defender, but I guess there's nothing you can do about that. Except with the Xbox Live Arcade and the Virtual Console with all the old stuff coming back.

EJ: That is cool. I always think that MAME has been a wonderful thing, too, in preserving the heritage of games. Graphics have moved on and gameplay has moved on, but it's fun to see and play [old games] and see the history of the business. It's a history lesson that's great entertainment in its own right.

What do you enjoy about making games that's made you stay in the business? It's still a hard market.

EJ: It's a challenge. It's a challenge of making something, putting a smile on someone's face, or seeing a kid get excited about your game. There's nothing better than seeing some kids playing Target Terror and laughing when you shoot a guy in the balls and he crumples over. For a designer, that's the ultimate reward, seeing people enjoying your game and fighting over who puts in the next quarter.

Ultimately, it's all about shooting guys in the balls.

EJ: [laughs] But yeah, that's the challenge. I think in the back of the heads of all game designers, once your design becomes a reality, no matter how good it is, [you want to make it better]. I mean, look at Will Wright. The guy has done SimCity and The Sims, and other amazing stuff. But now he's killing himself doing this Spore game. He wants to do the ultimate game. It's not enough to have 10 million people playing his games, he wants 100 million people playing his games. It's that never-ending challenge to make the killer game.

I feel like everyone's too afraid of sensationalism these days.

EJ: I think the problem is the budget. The smaller the budget, the more outrageous you can be. It's like with the big-budget Hollywood stuff; it's typically not that controversial. It's the lower-budget films that will take the risks, and it's the same thing in the games business.

I love doing this (game) stuff, and I always want to do something that will push it further and further. I'm always trying to duplicate the success of Defender. It's like I'm kind of doomed to never have that level of success again, and I keep dreaming.

I love doing this (game) stuff, and I always want to do something that will push it further and further. I'm always trying to duplicate the success of Defender. It's like I'm kind of doomed to never have that level of success again, and I keep dreaming.

It's possible! There aren't a lot of guys out there willing to push the envelope, and you seem like you're still ready to do it at some point. I'm still waiting to see what you come out with.

EJ: Alright, hopefully I won't disappoint you!

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like