Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Making Alto's Odyssey isn’t just about designing great flow, it’s also about improving the workplace culture for the people who make it too.

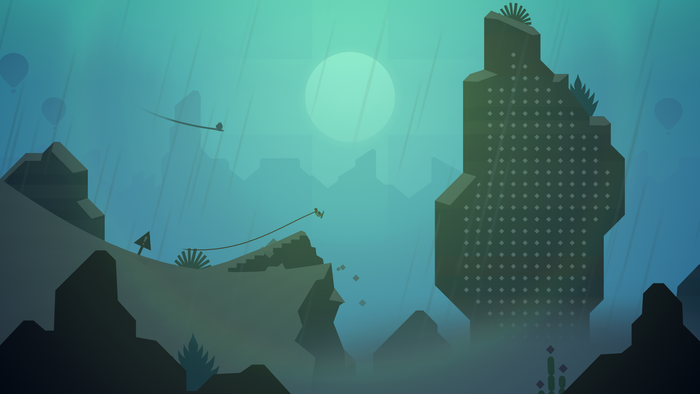

Snowman's Alto series, which now includes Alto’s Adventure, Alto’s Odyssey¸ and the Apple Arcade-optimized Alto’s Odyssey: The Lost City, has stood out as a leading series in the endless runner genre just based on how much it transcends the genre’s time-killing roots.

Though the Alto games have high scores, power-ups, and goals to drive gameplay as you board through endless runs, the series has carved out a space in the genre by not just being about high scores or high performance, but easing players into the kind of calm state of mind that makes better performance (and quality of life, really) possible.

Alto’s Odyssey’s success in succeeding not just on the traditional mobile market, but in jumping to new subscription world of Apple Arcade, had us wanting to talk to the folks at Snowman and Land & Sea (A partner studio founded with the goal of creating artful, hand-crafted experiences that resonate with a wide audience about their process for continuing work on the game.

Snowman co-founder Ryan Cash, as well as Land & Sea producer Jair McBain and lead programmer Joel Herber were gracious enough to chat with us about where Alto’s been, and why there’s a lot more than you might think going into the making of one of the most popular endless runner games on mobile devices.

When running just becomes vibes

The endless runner is a hit genre on mobile now, but it also thrived in the heyday of Newgrounds, and even on the TI-86 calculators used by middle schoolers everywhere. It’s a genre whose fundamental principles work even in the most simple environments, making it easy to expand outward with different kinds of theming, aesthetics, and goals.

To Cash, that’s been a huge inspiration for not only Alto’s Odyssey, but for finding and connecting with other developers working in the space. “It’s interesting to see just how much the genre can be explored,” he said. “I feel like it’s become more of a genre than just one type of game in the same way first-person shooters have.”

He described the current moment for the genre as feeling like those years when first-person shooters drifted further and further from Doom and Quake, evolving into games with their own identities while retaining the genre moniker.

So why has the genre done so well on mobile devices? “One of the reasons why it’s such a great fit for mobile is that it really lets you get into a flow state—which is just a beautiful state to be in a person, especially these days.”

With “these days,” Cash alluded to the real-world stresses his team is all-too-familiar with. A pandemic. Economic inequality. The impacts of climate change. Snowman started out trying to push into the world of Productivity apps like Checkmark, but became a game developer when it realized the endless boarding genre could accomplish a similar goal.

After Alto’s Adventure, that effort became doubly important with the development of Zen Mode, a mode for the Alto series that strips away the coins, goals, and score tracking of the core experience. It’s just the player, the board, and the environment. “I think it’s just important to have a moment of quiet,” he explained.

Herber also attributed the success of the Alto series to its primary focus on mobile devices. “Endless runners are an excellent format for mobile—what they ask of the player is immediately clear to most people. Your objective is to go from A to as far as you can.”

But in a more detailed analysis, he pointed out that the versatile set of mechanics emerging from that goal have been able to evolve and adapt as the mobile market’s shifted. In the move to free-to-play games, it’s a playstyle that adapts to simple free-to-play elements. But the game could simultaneously bend to the design of what works well in premium mobile titles.

There’s also the fact that the Alto games rely on what Herber called a “premium aesthetic.” It’s a look inspired by games like Journey and Monument Valley, and he said it allowed the team to match how Apple’s tweaked and shifted the iOS App Store. “It’s very easy for us to target new devices,” he explained. “It’s very easy for Apple to continue to feature our titles because we can reflect the values they’re looking to bring to the market as well as through their products.”

The Alto team’s relationship with Apple and Apple Arcade extends outside this particular series. Cash and the Snowman team helped launch Skate City and The Game Band’s Where the Cards Fall as Apple Arcade launch titles, while McBain worked on Mini Motorways with developer Dinosaur Polo Club before joining Land & Sea.

Cash and colleagues played coy when asked about what technical challenges remain when developing for Apple’s Arcade program, but he did share that the Alto team has paid close attention to the user interface and user experience of Alto’s Odyssey when they reworked it for the subscription service.

Grinding away

Just as Alto and pals pick up speed in the different Alto games, the series’ success has built momentum for Snowman to grow as a company. But when you’ve started building your company on a somewhat simple endless runner, and you find yourself needing to staff up to sustain operations and make new kinds of games, you run into the new challenges facing game developers at all studios big and small.

Those challenges include not only increased calls to improve work-life balance in game development, but also pushes to reduce toxicity in the workplace, and create professional environments that can foster diversity in the ranks.

Cash, McBain, and Herber (who admittedly, all happen to be white men), were all fairly frank about the challenges their end of the industry still faces. Diversity at mobile game studios hasn’t caught as much attention as the stories of what’s allegedly happened at Riot Games and Activision Blizzard, but they’re still there.

“It’s easy to say ‘hey, if anyone’s ever making you feel uncomfortable, you can come talk to me, this is a safe space,’” Cash said. “but I think actions speak louder than words there. It’s not always as simple as that.”

As Snowman has hired up, Cash said team has tried to emphasize finding people who can help maintain a safe, professional environment, even if it means passing on candidates who seem to be a 10/10 skill fit.

If you’re prioritizing culture fit over skill, even in the name of maintaining a safe work environment, can’t that create similar problems?

Cash took the question head-on. “The key to solving all these problems and making sure that your studio evolves in the right direction…is laying out really solid company foundations at the outset,” he said. “I think a lot of companies from the early days set out to make great games, or they set out to sell to investors within five years, or they set out to have an exciting party culture…you absolutely have to set out with people in mind first.”

“That way, when the culture does inevitably evolve beyond what you’ve set up—because you can’t ever control it all the way through—everyone who comes on can bring something new to that.”

Herber was quite frank about some of his experiences at prior studios. “Some of the biggest problems that I’ve had in games companies is that they treat this as a solved problem,” he explained. “They say ‘oh, we’ve solved the culture problem, we didn’t have to strive to be better.”

He talked about how companies might let their action on the subject be a thing of the past, rather than a consistent process. At Land & Sea, he says the team is prone to talking about this problem “all the time."

Even with a small team right now, he says the company is aware that if they expand, it’s possible that they might not learn problems exist until it’s too late—unless you’re consistently talking with people, and giving employees forums to voice concerns.

The rest of this conversation took a spin toward discussing how much has changed in the game industry—and what needs to still change with regards to representation and opportunity. Cash did follow up in an e-mail after our chat though, saying some of what we’d talked about was still at the top of his mind.

“At Snowman we’ve built a culture that very transparently stands against all forms of harassment. We hire new employees very carefully and thoroughly to ensure new hires also share these values,” he wrote, before owning up to the fact that the team still had room to improve on how diverse its staff actually was.

“While we care deeply about both subjects, we've got a lot of room to improve and it's something we will be keeping top of mind as we grow further.”

There’s a direct connection between the Alto team’s desire to make games that help people’s moods and its own reflection on building better workspaces. It’s difficult to build products meant to have a positive impact on players if you’re not also reckoning with the values meant to shape that positive impact.

And to their credit, these are the same issues affecting developers working in more conventional spaces too. Starting a company with your friends, then growing to hire people you might only ever meet on Slack (especially in a COVID-19-shaped world), means you don’t just get to have fun jam band sessions forever.

We did say there’s more than meets the eye in making an Endless Runner like Alto’s Odyssey. Some of that’s in evolving the simple genre. Some of it’s also in making sure you’ve got the right people doing the shaping.

Updated 9/7 with corrections to Joel Herber's name, a paragraph that mistakenly said Snowman began working on apps such as Calm and Headspace, other grammatical issues.

You May Also Like