Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

As Hohokum heads to Steam and celebrates its 8th birthday, we sit down with co-creators Richard Hogg and Ricky Haggett to delve into the creation of the whimsical adventure.

Revisiting Hohokum after close to a decade is intoxicating. The effervescent, swirling toybox has lost none of its giddy charm, and coasting through levels as the aptly named Long Mover (yes, that is an unashamed Mighty Boosh reference) remains a uniquely therapeutic experience.

Plunging back into the frenetic, pulsating playroom is akin to reacquainting with your favorite record after months or years apart. As it spins on the turntable, the lyrics and chords will come flooding back through the crackling static, but you'll also find yourself re-discovering nuances and layers that had somehow become lost among retreating tides of memory.

I know that sounds overly indulgent. Pretentious, even. But anyone who's familiar with Hohokum will know words alone struggle to capture the heady brilliance trickling from every pore of Sony Santa Monica, Honeyslug, and Richard Hogg's ode to play. It remains a game that's almost impossible to describe using even our vast lexicon, and unfurling the ineffable mysteries that have become the title's beating heart was as much a challenge for Hohokum art director Richard Hogg and lead programmer Ricky Haggett as it remains for players.

During a recent chat with Game Developer, Haggett and Hogg explain the title started life as something altogether more conventional. The two friends had come together to work on a video game project based on some of Haggett's sketches, which, while vastly different from the finished product, contain plenty of Hohokum's offbeat DNA.

"I was literally drawing things and sending them to Ricky and going 'I don't really know what this would be in video game form, but maybe it could be something?' I was drawing all sorts of strange things," recalls Hogg.

Haggett, meanwhile, started building prototypes using placeholder art and pitching those back to Hogg. That back-and-forth, says Hogg, resulted in the duo "approaching the problem from both ends" in a bid to figure out precisely what their "something" could be. The prototypes themselves were in a constant state of flux. At one point, Haggett spent months creating new working concepts on a near-daily basis, morphing and molding those early iterations of Hohokum in an attempt to discern which mechanics worked and, crucially, which didn't.

One of the very first sketches Hogg sent to Haggett depicting a vibrant machine

"I was playing around in flash and making physics demos. In one, I toyed with the idea of getting players to fly around [in a ship] and mine materials to power up attractors that would then pull other materials towards it," he says, noting how those early versions were far more reliant on puzzles and tangible objectives.

Although Haggett acknowledges those ideas could have been made into a functional game, he says that both he and Hogg never felt enthusiastic enough about those concepts to take them any further. "Because we never had the time pressure of having to finish the game," he continues, "it meant that we could just make a thing, park it and live with it for a while, and then ask ourselves 'is this what we want to make?'"

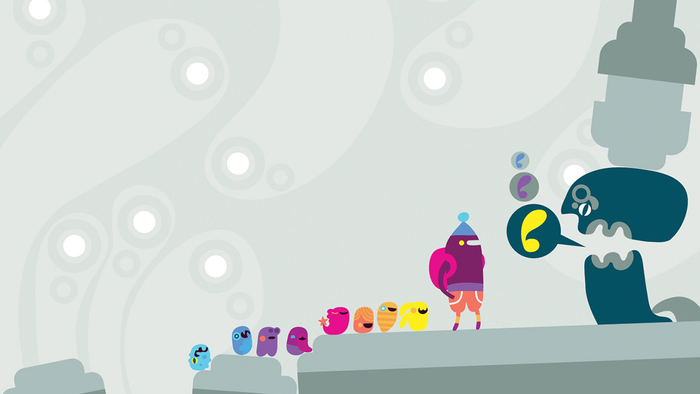

One of the earliest versions of Hohokum asked players to create networks of power and collect materials

There were other variants, too. Some included bombs and other decidedly lethal hazards. There was one with a charming golf mini game that would see players punt characters into whirling contraptions. Another cast players as a vaguely humanoid figure who had to herd up whimsical critters to unlock musical gates.

A singing door and musically infused critters that Haggett conceived as the game found its musical sensibilities

From there, Haggett started tinkering with motion and music, adding a line mechanic that allowed players to ferry diminutive denizens around via the magic of cosmic chemtrails. The evolution towards the finished product was slow but visible, but it still hadn't clicked.

In pursuit of finding that moment-to-moment fun, Hogg posed a question. What if they simply got rid of the player character and allowed them to become the line? It was a decision that helped move Hokohum further into the abstract, but the pair were still struggling to nail down exactly what they should be asking players to do while zipping around their nebulous space.

"I remember showing one prototype to Richard, and him just asking 'Why do we need this guy? Why can't we just be the line?' So then we made it an arrow, and it was a line with an arrowhead. Then we made a prototype where you needed to help band members get to a gig, almost like a roadie," says Haggett.

"Then we started talking to my brother Rob, who was a musician, about making some music. We'd made this little prototype that had attractors and repellers [that you could interact with] as part of a race where you had to quickly fly through these gates really quickly. Then when you won the race a door would open — and the conceptual idea was that you'd go through this door into a series of rooms where you'd do tasks. But there was nothing outside the room."

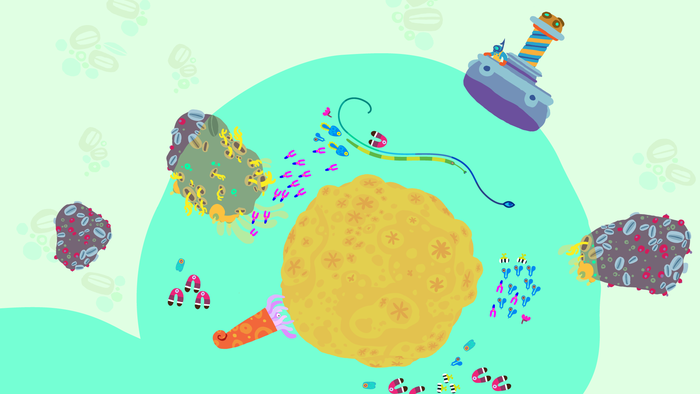

Hohokum as we know it begins to take shape

As Haggett and Hogg played that version of the game with Rob, discussing what the music he might compose for the finished version, something both innocuous and formative occurred. Rob finished the race during their conversation and became transfixed with simply being able to fly around the empty room at the end of the level.

"We were listening to that song, 'Lovely Allen' by Holy Fuck, and Rob was just in the middle of nowhere," adds Haggett. "There was nothing on screen [...] but he was just flying and doing loops and moving really quickly, and we realized this is way more fun than all the stuff we would've put in the rooms."

Hogg explains that to suddenly be free of mechanical barriers, watching Rob soar around infinite space in harmony with music, was the moment he realized "this is the game."

"The thing we were trying to make before was very contained and claustrophobic in a very video gamey way. It was like, 'oh, you have to hit this thing and then you've only got a few seconds to get to this thing,'" he adds. "All the time players were trapped inside this platform level."

After that, Haggett and Hogg iterated quickly. They created a prototype fairground level for the Eurogamer Expo that was inspired by Portmeirion in North Wales. It contained a number of characters that would appear in the final game and was stylistically far more in line with the finished article. But the duo still found themselves attempting to cram more traditional game elements — overt fetching tasks and obstacles such as bombs — into the project. Yet, as was the case before, players remained largely uninterested in those mechanics.

"At the top of the level — above where the bombs were falling — we just placed all these vines and repellers to create a little playground zone that contained all the other elements we quite liked," says Hogg.

"Yeah," chimes Haggett, " I remember watching people play [that version] and just spend the majority of their time flying around that play zone. It was like they thought 'let's just fly around among these lovely vines.' So we continued to realize that maybe the project needed to be way more chill."

Hogg describes the gradual shift towards Hokokum's final zen state as a "personal journey." At that stage in their career, both Haggett and Hogg were still attempting to figure out what sort of games they wanted to make, and perhaps more crucially, what kind of games it was acceptable to make.

The Eurogamer build is instantly recognizable, but features numerous hazards that didn't make the final cut

"You know, you're an indie developer trying to make something interesting," says Hogg, "but I think there's still, even unconsciously, a lot of pressure on you to make something that people recognize as being a video game. Maybe that means bombs falling or something else. I don't know about Ricky, but I was still figuring that out. I just knew I wanted to make something that felt emotionally different from a lot of video games."

Realizing your project is at its most engaging when shirking bread-and-butter mechanics and clearly defined pathways might've overwhelmed some developers. But Hohokum remains a unique morsel because there's a thrilling lack of direction from the outset, letting players chart their own course through a litany of mesmerizing worlds in the name of jaunty exploration and joyful interaction. As they sought to build out the title and stitch its disparate levels together, Hogg and Haggett had to learn not to care too much about how the puzzle might be pieced together.

"We were just making these places and putting them together in a. world. It took us a long time to hit upon a framing or story to explain why you're going to all these places, but we weren't that concerned about discrepancies between them," says Hogg. "Even though the game is quite abstract, we wanted it to feel authentic and like a real place."

Hohokum's levels are kaleidoscopic in nature

In the world of video games, realism is often achieved by reducing the uncanny valley to rubble using technology like physics and lighting to create a world that behaves and looks like our own. On the surface, there's nothing 'real' about Hohokum, but Hogg and Haggett felt they could give players something that felt authentic by refusing to hold their hand.

"In real life, you could go on holiday to Paris for a weekend, and it's not like a video game right? You can go anywhere you want in Paris," says Hogg. "You know, [in the real world] you don't have to visit certain things in one area before another unlocks.

"Hohokum is a bit like that, right? You can go anywhere you want in the game in any order. You can get very lost. You can find yourself circling back to the same place, and you can just go experience the bits you like and not bother with the bits you don't. The game doesn't really care. In that sense I think there's a sort of realism to it. I replayed it recently because of the PC launch, and I found that really refreshing."

Although he found that sense of freedom liberating, Hogg concedes it might leave some players feeling frustrated. Talking about his latest playthrough — almost eight years after the title launched on PlayStation 3 — Hogg suggests the game could, perhaps, have used more effective signposting.

He acknowledges the game doesn't make it clear which interactables will deliver an outcome and which are simply there as set dressing. "The game was really inconsistent in that sense," he says, "and I remember feeling quite strongly about it at the time but I can see that, from a player perspective, that inconsistency might undermine your confidence."

For instance, Hogg claims there are still some hidden secrets in the game that have yet to be unearthed by players. "If anyone has found them, they didn't put it on social media," he explains. "As far as I know, there's stuff in the game that nobody has ever found."

Haggett is less critical of those perceived shortcomings. For him, those inconsistencies are part of the experience, and to add clarity might detract from what made Hohokum so special in the first place. "I definitely wouldn't change any of those things," he says. "For me that's what make's Hohokum feel unlike anything else. Even in games that are more obtuse, it's still clear what you're supposed to care about and what you're not. Hohokum literally makes no distinction between a thing that's just an irrelevant toy and a thing that's a core part of gameplay. I think there's enough people who love Hohokum for the fact it's a game that will just trust you to figure it out."

The concern for Hogg is simply whether people can get on board with that seemingly radical notion. He talks about valuing the player's time, and worries that people who perhaps don't understand Hohokum's playful nature will feel like they're just banging their head against a brick wall. For instance, he claims that Hohokum was never going to be satisfactory for completionists and laments that the game had to include achievements, which ultimately serve as arbitrary goals that exist simply for the sake of existing.

"I do think the game is really rewarding," continues Hogg. "I just think in that particular use case — with someone who feels the need to have done all the things and tick all the boxes — then it's probably going to frustrate those people. Maybe 10 years ago I would've been like 'fuck those people,' but now I have more sympathy for them."

Still, Hogg would never dream of tweaking Hohokum in a bid to satisfy those players. "We made a decision not to change the game," he adds. "We didn't want to change anything about it, because you can't do that with art. George Lucas has proved what a fool's errand it is to do that."

Sony Santa Monica, which signed Hohokum shortly after the project made an appearance at Indiecade — even though Sony rep Nathan Gary couldn't actually play the title at the expo because of the fervent dedication of a young superfan who came back three days in a row specifically to play Hohokum — was also incredibly supportive of Haggett and Hogg's trippy vision.

Haggett says the pair spent a lot of time talking with Sony Santa Monica about the title, noting how the publisher went above and beyond to ensure they felt supported in following their more outlandish ideas. Hogg agrees, explaining how he'd often feel the urge — even further down the line — to make something a bit more conventional because of concerns about player perception, and how the reps at Sony Santa Monica would push back and encourage them to chart their own path.

"Making Hohokum really felt like going out on a limb in a lot of ways," says Haggett. "We just made so many mechanics and characters and places and animations. You know, making all of that work to the extent that it makes sense, and then figuring out how you get players into levels that complicated — it all just felt really terrifying at times. It was really good to be working with people who weren't trying to give us loads of weird artificial pressure and trusted us to figure it out."

Those animations, in particular, proved to be one of the most grueling aspects of production. Hogg was essentially tasked with drawing the entire game, and admits that by the time it launched he was "quite burnt out [...] because I was the bottleneck." Although he had people to help with the animation — professionals brought in from the world of film and television — Hogg still needed to stay ahead of them, because in order to draw the world and characters it was important to figure out how those elements would animate. According to Haggett, that specific part of production was like driving a train while frantically trying to lay down track in front of it.

During our chat, we inevitably begin discussing Hohokum's musical credentials. The title plays out in tandem with a syrupy soundtrack that features artists like Matthew Dear, Tycho, Com Truise, Ben Benjamin, Kiln, and more.

From minute one, Hohokum becomes a ritualistic dance between player and maestro, letting them plunge into oceans and soar among the stars in tandem with ethereal melodies that are stitched into the very fabric of the game. It feels like one couldn't — or at the very least, shouldn't — exist without the other, and it seems like Hohokum's now-iconic soundtrack was fated from the beginning.

"There was a process at the start where we made a playlist of tracks that we liked, and then we showed that to the music licensing person at Sony," explains Haggett. "He was like, 'oh, a bunch of these artists are signed with Ghostly. I know the person who runs Ghostly, why don't we talk to them?"

Ben Benjamin created the track Air Parsing specifically for the pottery level

After Sony made contact with the label, they were sold. A deal was struck that would allow Haggett and Hogg to use anything they wanted from the Ghostly back catalog, as long as the artists themselves had access to all the stems. Those were required so each track could be layered into Hohokum to respond to player movement. Hogg and Haggett also managed to get their hands on some unreleased tracks after speaking with the artists themselves, including perhaps Hohokum's most famous piece of music.

"Some of the artists [like Tycho and Shigeto] offered us some demos. Almost the most famous piece of music in the game — 'L' by Tycho — was unreleased when we were working on the game. By the time the game came out I think it was in an Apple ad," laughs Hogg, "but I still feel like it was our track."

To get those artists onboard, Hogg and Haggett sent out concept art to hopefully sell the idea. That resulted in some musicians creating tracks specifically for the game. "Ben Benjamin was super into it, and he made his music for the pottery level (a track called 'Air Parsing') with reference to some of the PDFs that Richard sent over — become some of the levels didn't really exist at this point," says Haggett.

"Then for a bunch of the levels that didn't have custom music, we'd have a shortlist of tracks that we really liked and we'd try them here and there, shuffling them around. Towards the end of the game there was a bit of a shuffle where we cut some levels and repurposed a lot of assets into other levels. So the wedding level features characters from one level and assets from another level, so it was a case of mixing [things up at times]."

Balancing movement in Hohokum also required a similar amount of iteration, and even though the basic control scheme never really changed from the very first prototypes, delivering the sense of kinetic nirvana that has become Hohokum's signature required plenty of tinkering.

"We were constantly finessing the whole time," recalls Haggett. "Gravity changed a lot. The wiggle boost stuff — where you can sort of wiggle through the air to get a speed boost — changed a lot. We were just constantly tweaking numbers all the way through development." Hogg jokes that movement was only finalized the day before they shipped, and says they didn't really know exactly what they were shooting for until, one day, it "just felt right."

With Hohokum now on Steam almost a decade after it debuted and well over a decade since development started, I'm curious to hear whether Haggett and Hogg feel the weight of expectation as some people presumably prepare to play the title for the very first time.

The short answer is 'no.' Sounding laid back about the title's prospects on Steam, Haggett suggests that if Hohokum was making its full debut in 2022 it might've actually had an easier ride in terms of getting people to buy into its weirdness, and says that one of the biggest wins of launching on Valve's marketplace is being able to preserve the title's legacy by ensuring that more people will be able to jump in.

"I can think of people in real life who've never had a PlayStation but who can now play Hohokum," agrees Hogg, who added that he's approaching the title's multi-platform pivot without any real sense of expectation. "I think Hohokum just finding an audience [is a win], particularly because I think a lot of people that Hohokum might appeal to are probably people who aren't big gamers — just normal people," he continues. "So hopefully those kinds of filthy casuals are going to find it's more accessible to them now."

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like