Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Wednesday March 10, 1998. I'm the audio/video producer for Electronic Arts' hit game, Madden NFL Football for the Sony Playstation, Nintendo 64 and PC. I'm the guy who puts Madden into Madden, and today is the first of the only two days a year that we actually get to film the Great Man himself. This isn't any old football game, it's John Madden's football game, and that means something to our customers. Madden's face and voice are a key part of the experience even if they don't affect the gameplay. That's the part I create.

Wednesday March 10, 1998. It's 7:45 A.M., and I'm nervously sipping coffee in one corner of a cavernous television studio belonging to pro football megabroadcaster and Super Bowl-winning coach John Madden. I've been up since 5:30, I'm freezing my butt off, and the Ultimatte guy has called to say there's fog on I-680 and he's going to be late.

The reason I'm up at this godawful hour -- my normal workday runs from about 10 AM to 7 or 8 (or 9 or 10) in the evening -- is that I'm the audio/video producer for Electronic Arts' hit game, Madden NFL Football for the Sony Playstation, Nintendo 64 and PC. I'm the guy who puts Madden into Madden, and today is the first of the only two days a year that we actually get to film the Great Man himself. The reason I'm nervous is that I'm just about to spend around $100,000 in sixteen hours flat. These are the two most expensive days in the production year, and if I screw up - and if the Ultimatte guy doesn't show, that will qualify - I probably won't get a second chance. Somebody will eventually do it again, at great cost and inconvenience, but it won't be me. I'll be history.

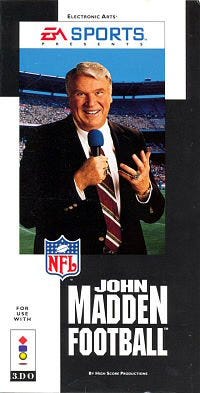

Madden NFL Football is EA's flagship sports product and its longest-running franchise. The original John Madden Football was first written in back in 1989 for the Apple II, if you can believe that. I wasn't at EA then. I joined the company in 1992, hired as a software engineer to write their next PC baseball game, the successor to Earl Weaver Baseball. Not long after I got there EA discovered they could make ten times as much money developing Genesis and Super Nintendo titles, and they dropped PC baseball with little ceremony. My producer, the legendary Scott Orr, liked some comments I had written about the design script I was working from, and he asked if I wanted to quit programming and be a lead designer in his new production group. Although sports was not my favorite genre, the opportunity to be a game designer for Electronic Arts - in any capacity - was too good to pass up. In 1993 the company began to support the short-lived 3DO Multiplayer in a big way, and of course Madden had to be on it. It was EA's first-ever sports game for a CD-ROM platform, and I got to design it.

Five years and five Maddens later, I'm watching as taciturn, muscular young men and women begin to move around the vast sound stage, warming up video gear and lighting. I don't know their names; I hired a production company, and it supplied them. I'm in charge of this shoot, but most of the time it runs itself. This is a good thing, because I don't have any formal training to be an A/V producer. The 3DO machine was the first device EA had ever supported that was capable of playing video (after a fashion), so the company insisted that Madden 3DO include a lot of it. As the designer, it fell to me to decide what to create, then script it, shoot it, and edit it. Suddenly, and without meaning to, I became my group's video guru. Subsequent editions of Madden for the new generation of consoles didn't really need a full-time designer, but they did need A/V production and I was elected.

years and five Maddens later, I'm watching as taciturn, muscular young men and women begin to move around the vast sound stage, warming up video gear and lighting. I don't know their names; I hired a production company, and it supplied them. I'm in charge of this shoot, but most of the time it runs itself. This is a good thing, because I don't have any formal training to be an A/V producer. The 3DO machine was the first device EA had ever supported that was capable of playing video (after a fashion), so the company insisted that Madden 3DO include a lot of it. As the designer, it fell to me to decide what to create, then script it, shoot it, and edit it. Suddenly, and without meaning to, I became my group's video guru. Subsequent editions of Madden for the new generation of consoles didn't really need a full-time designer, but they did need A/V production and I was elected.

Fortunately, the production company works with such quiet professionalism that its people don't require much direction, and I just let them get on with it. Right now their activity centers on a grotesque sculpture in the middle of the studio, a latex Ronald Reagan mask wearing a cheap white wig, and impaled on a tripod. Below the mask hangs a navy blue blazer on a hanger. This bizarre homunculus is John Madden's "lighting stand-in." We can't afford to have Madden standing around for hours while we get his lighting right, so this thing serves in his place - Madden's hair is completely white, and the blazer is a duplicate of the one he'll wear later. The tripod is cranked up to put his "face" at the correct height.

The video people tell me that this is one of the best facilities in the Bay Area. Madden won't fly and he doesn't want to travel more than he has to - after all, he travels constantly during the football season - so rather than go somewhere else to film his commercials and other projects, he built a studio in his home town, Pleasanton. He didn't spare any expense, either: the walls and ceiling are extra-insulated so traffic noise never disturbs the recording, and the air conditioning is specially muffled. The sound stage is huge, the size of a couple of basketball courts, and about three stories high.

Today we'll be filming, or more accurately, taping, John Madden and his broadcasting partner, Pat Summerall. We're going to shoot a number of short clips of Pat and John sitting together, apparently in a stadium broadcaster's booth, discussing the game that the player has chosen to play. These clips aren't used for most regular season games, but if it's opening day, or a Thanksgiving Day game, a playoff game, the Super Bowl, or the Pro Bowl, then the player will get to see one of these intros before the game begins. Of course, we have no way of knowing in advance which two teams will be playing in the game. There will be 31 teams in the upcoming NFL season, and they can theoretically play each other in 465 possible combinations. We can't shoot 465 clips - apart from the time it would take, there isn't room on the CD to store them all - so the material we're recording has to be generic. They'll talk about the weather conditions, Madden's preference for real grass fields, the significance of the game at this point in the playoffs, and so on.

Tomorrow we'll finish taping Pat and John and move on to James Brown, our EA Sports Studio host (and actually the anchor of Fox's broadcasts). J.B. is a warm and extremely funny man, and a positive delight to work with. Harvard-educated, he occasionally does the material we've written for him in a homeboy vernacular that has the whole crew howling with laughter. We can't ever use it; in fact some of the things he says we don't even dare show to anyone outside the team. But over the years we've assembled a hilarious private collection of out-takes.

After five years of doing this it's familiar now, but I'm still worried about the missing Ultimatte operator. An Ultimatte is an expensive piece of gear that makes a person standing in front of a blue (or green) screen look as if he's standing somewhere else by superimposing, or "matting", his image onto a background image - in our case, the stadium broadcaster's booth. This "booth" is actually a computer graphics image created by our artists. It's not a single image but an endless loop so that it looks like there's a little movement in the crowd outside the windows. The crowd is deliberately out of focus so it won't be too obvious that it's just a loop.

Matting, or "keying" as it's called in television terminology, is a standard trick to save money. But an Ultimatte is a fiddly device; it takes forever to set one up and get it tweaked just right. For one thing, the lighting on the subject has to match the lighting in the background image. Otherwise the whole thing looks wrong: you see someone who's brightly lit in a dark place, or lit by yellowish light while the background is lit by bluish light. We spent all day yesterday getting this figured out, and now everything should be dialed in correctly. But we still need the Ultimatte guy here to do the shoot. I can't afford to have Madden, Summerall, and a whole video crew standing around waiting for one person.

The teleprompter operator comes over to talk to me. Her gear is ready to go, but she needs the floppy disk that contains the script. The teleprompter is a clever device, a laptop computer connected to a monitor mounted below the camera, facing upwards towards the ceiling and displaying the script - backwards. A one-way mirror in front of the camera lens inverts the words into readable text and reflects them towards the talent. The camera looks through the mirror from behind and doesn't see the words, but Pat and John can read them while looking straight into the lens. They won't simply read whatever it says, though, because we're trying to create the impression of an impromptu conversation between the announcers, the kind of thing that normally precedes a football broadcast. They'll look at the teleprompter before each take in order to get a sense of what we want, then improvise somewhat on the material I've written. We often make changes as we go along. If we find that Pat or John is consistently stumbling over a line, we'll type in something new. I was up late last night making changes to the script - as usual, at the last minute the marketing department wanted some material of their own added - which is why it wasn't ready until now.

There's a legend around EA that the first time somebody wrote an audio script for John Madden, they didn't put much effort into it: just wrote a lot of generic football commentary. Madden took one look, threw it down, and said, "I'm not going to read this s---." For several years after that, all the voiceover audio in the game was ad-libbed. Because it consisted only of "Maddenisms" - short interjections like "Boom!" and "Where'd that truck come from?!" - on the Genesis and SNES, this didn't matter much. But when the time came to do the 3DO edition, we needed a lot more material, and that meant a real script. In order to produce something that he would be willing to read, I became an expert on the Madden persona. I transcribed three entire football broadcasts word-for-word. I studied his vocabulary and grammar, his inflection and pacing. Finally, in great fear and trepidation, I gave him my script. The work paid off. He read it, performed it, and didn't complain. Madden seldom praises anything. He's still a football coach at heart; you can tell he's pleased with you if he's not tearing your head off. Once I accidentally typed "backtracking" when I meant "backpedaling" - the motion linebackers make when they're backing up and watching the quarterback at the same time. John stopped short and spent the next two minutes telling me in no uncertain terms that "backtracking" was not a word he ever had, or ever would, use in his life.

The wardrobe and makeup staff arrive. They didn't have any trouble with the fog. I hurry off to select shirts and ties for John and Pat. We decide on light blue for John, but light yellow for Pat because he's rather pale and we're hoping to warm up his complexion a little. And no printed ties. The ties must be solid; I told the lady that, very firmly, on the phone when we made the deal. The first time I did this job, some idiot (me) allowed John to wear a patterned tie. The early video compression algorithms worked by detecting areas of low and high detail in the image, and saving disk space by making the areas of low detail blurry or blocky, under the assumption that people aren't looking at those regions. But the compressor doesn't really know which parts of the image are important and which aren't. The damned algorithm for the 3DO took all the available detail and gave it to Madden's tie instead of his face. John ended up looking like The Thing in a suit.

Our audio engineer walks in. In addition to miking up Pat and John for the video shoot, he'll be spending a lot of time in the nearby audio suite. Video recording is only a small part of what we're doing here. For several days after the video shoot is done, we'll have Madden or Summerall in the audio booth, recording play-by-play, color commentary, and voiceover narration for movie clips. I've spent the last several months writing this material. I've researched the current status and future prospects of each team in the NFL, and my assistants did the same for dozens of star players. Then we wrote color material in Madden-ese for him to record about both the teams and the players. ("Warren Sapp is one of those guys that, even when he's double teamed he's still gonna cause you trouble.") For Summerall's play-by-play, we've written and re-written hundreds of pages to try to cover every reasonable eventuality that can occur in a football game. One year I forgot one: turnover on downs. It doesn't happen that often, but when it does, you need to say something. I left it out of the script, and whenever a turnover on downs occurred, Summerall was strangely silent.

You would think we could just re-use all the material every year, but we can't. Players come and go, team names do change sometimes, and besides, we need to write new Maddenisms to keep the game fresh. The problem is, you can't use audio from different recording sessions. People's voices change from year to year, and the recording conditions are never exactly the same. If we mixed material from different years, the customers would notice it immediately, and it would quickly become distracting. We're trying to create the illusion of a live football broadcast, so it needs to be seamless and unintrusive. That's why we want to record all the material during several days in succession, to keep the recording conditions as stable as possible. It's long, grueling work, especially for Pat Summerall. He has to record the names of all the key players in the NFL, hundreds and hundreds of them, three times with three different inflections: one each for the beginning, middle, and end of a sentence.

Here's the Ultimatte guy. It's nine o'clock and John's due on set in half an hour. My stomach unclamps enough to admit a bagel. There's quite a spread here: doughnuts, pastries, bagels, and several flavors of cream cheese along with coffee, tea, and fruit juices. That's one great thing about filming at Madden's: the food is wonderful. Madden is famous for believing in eating well and it's not just a gag. In between the sound stage and the rest of his offices is a first-class kitchen, complete with Wolf range, giant Sub-Zero refrigerator and everything a professional chef could need. And in fact, at this very moment a professional chef is busy in there, cooking and assembling a six-legged turkey.

This is sort of an expensive joke. Madden always broadcasts one of the Thanksgiving Day football games. When a player does particularly well, he says, "Give that guy a turkey leg!" But he often says it more than twice a game. Eventually he got someone to make up a six-legged roast turkey (the extra legs are held on by hidden wooden skewers), and served the legs to the players after the game. One of our pre-game clips is for a Thanksgiving Day game, so I'm having a six-legged turkey made, and after we finish shooting it, we're going to eat it. Everybody - Pat and John and James Brown, along with all the EA people and the video crew - will sit down together on long picnic tables in the studio and have a whopping big lunch.

Madden divides all food into "sinkers" and "floaters." Salad, bread, and vegetables will float, so they're no good for football players or tailgate parties. Things like sausages, barbecued ribs, and potato salad are sinkers, food that keeps you anchored to the ground. In addition to the turkey we'll be having something Madden discovered on one of his journeys in the Madden Cruiser: terducken. A terducken is a boneless turkey stuffed with a boneless duck stuffed with a boneless chicken stuffed with - stuffing. It's very tasty, and definitely a sinker. Tomorrow I think we'll have a barbecue, cooked on a grill so large it can be towed behind a car.

Pat Summerall's limousine pulls up. Pat flew in from his home in Texas yesterday and spent the night in a nearby hotel. Pat's a down-to-earth guy and I think he would have been content with an ordinary taxi, but we want to do everything we can to make him comfortable and happy to be here, since he likes to travel even less than John does. Pat in person is exactly like Pat on TV: a tall, imperturbable man with a dry sense of humor and a wonderful speaking voice. He also has a fund of sports stories that go back decades, including some truly scurrilous ones about Howard Cosell. The only problem with working with Pat is that, without the excitement of a real game going on, his voice doesn't have the same energy that it does when he's broadcasting live.

This isn't an issue with John. When we need for John to be energetic, he's energetic. The loud, boisterous Madden we know from football and TV commercials is a created persona that he switches on and off along with the microphone. It's not phony - it's the real Madden, sui generis - but it is to some extent a performance. If he were like that all the time, he'd be intolerable.

One of the things I realized in the course of working with these guys is that they're broadcasters, not actors. Their job is to describe and discuss a football game in real time. In live television, you do your best at each moment, but if you make a mistake, you shrug your shoulders and go on. They're not used to doing take after take until it's perfect, and they get frustrated if they have to do something more than four or five times. In certain respects it would be easier - and far cheaper - if we could use sound-alike actors for the audio material, but John would never sit still for it and the customers would almost certainly spot it if we tried. There's only one Madden.

Pat disappears into the makeup room for a quick haircut and to change into his broadcasting outfit. Unannounced, Madden comes into the studio from his office in the front of the building. He's even bigger in person than he seems on TV, and everywhere he goes he walks with the same slow, heavy tread. He's wearing a nylon track suit, running shoes, and a baseball cap. He'll keep the running shoes on throughout the shoot, even while he's wearing his blazer and slacks on camera. They won't show and they're more comfortable. "Morning, Coach." I say to him, and he replies "Morning, Ernest" and that's it. We don't normally make small talk with him unless he seems like he's in a mood for it. He's one of the most famous faces in America; he meets a zillion people a year and most of them want a piece of him somehow, so we leave him alone. He looks around a bit at all the activity and then wanders off to say hi to Pat, whom he hasn't seen since the Super Bowl.

Madden always seems slightly bemused to see me. Once glance can tell him I'm not a football guy or a jock of any sort. This year I've allowed my assistant producers, who've written a lot of the audio material, to come along and sit with the audio engineer in the sound booth. They're more John's kind of guys: lively, cheerful, profane young men, all very knowledgeable about football and looking forward to the upcoming NFL draft. I'm hoping John will enjoy meeting them.

I'm not really a central member of the Madden team. The executive producer, the technical director, and all the many associate and assistant producers - to say nothing of the huge development staff - are the truly vital people. They're constantly worried about the code and playbooks and player AI, physics, user interface, athlete ratings, motion capture, animations, textures, and testing, testing, testing. The essence of the game is the gameplay - a carefully-tuned balance between fun and realism, and the guys who make that happen are the heart and soul of the team. The A/V producer is on the fringe. What I make is the façade of the game, its outward image.

It's important all the same, though. Without it, we wouldn't have Madden, we'd just have a football simulation. This isn't any old football game, it's John Madden's football game, and that means something to our customers. Madden's face and voice are a key part of the experience even if they don't affect the gameplay. That's the part I create. Most of John's color commentary consists of whole sentences, chunks of audio that are played whenever circumstances merit it. After each play the software checks to see if one of a long list of events has occurred, from most important (a score) down to least. If one has, it plays a suitable audio clip for the most important event. For example, if a receiver was wide open when he caught a pass, John might say, "The defense had better find some way of stopping that, or they're gonna run it all day." Then that remark will be checked off the list and won't be played again for a while so the players don't get tired of hearing it. For each event there are usually five or six clips that the software chooses from at random.

Pat Summerall's play-by-play is considerably more complicated because it's full of names and numbers. We're perfecting a technique that I pioneered at my previous job, assembling sentences on the fly out of fragments. In order to make this sound natural, the inflection has to be just right in each fragment. You can't get that by recording the fragments individually; you have to record each one in the context of a complete sentence, then cut away the extraneous material afterwards using a waveform editor. But as people speak they tend to slur their words together, and this can create problems when we're trying to cut up the audio. In order to create a distinct break between the part we want and the rest of the sentence, we make sure that the last consonant before the beginning of the fragment and the first consonant after the end of it is a T or a K-sound. For example, if we want to record the fragment, "Ball on the…", we'll record it by having Pat say "Ball on the two yard line." If we had him say "Ball on the nine yard line" the word "the" would slur into the word "nine" and we wouldn't get a clean cut. Similarly, if we had him say "Ball on the eight yard line," Pat would pronounce "the" as THEE rather than THUH, which wouldn't work with the other numbers. This occasionally means writing some odd sentences, but the odd parts will never be heard. Only the needed fragments will be used, and if we do it right no one should be able to tell that they're fragments at all when we actually hear them in the game. All the customers should hear is seamless, uninterrupted play-by-play. That's the theory, anyway.

In addition to the game itself, the PC version will have a second CD full of "football stuff." PC players tend to be older and demand more for their money than console players, so the previous year we created something called Madden University. We'll have a little movie about each team that discusses their prospects for the coming year. I've written the voiceover narration for this, and Madden will record it in the audio booth. I'll be spending the rest of the spring and summer looking through hours and hours of footage from NFL Films to select the best clips to illustrate it.

We're also trying something new this year: recording Madden while he uses the Telestrator, the device that lets him draw on the video image during games. The Telestrator is very much a part of Madden's on-air persona, and we wanted to get it into the game somehow. He'll use it to explain basic football terms: zone defense, trap plays and so on. We'll record his explanations in the audio booth. Capturing video from the Telestrator is much easier than a full-scale shoot because we can send its output directly to videotape. For that part of the work we won't need the cameras, lighting, Ultimatte, and all the people that go with them.

It's now 10 AM. Pat and John are dressed and they come in to take their places, side by side in chairs in front of the green screen. We're already half an hour behind, but I've built in a margin for delays and we're well within it. We make a last few lighting tweaks, and I go around to check that everything is where it needs to be. Even though I'm nominally the boss, when I'm not actually directing I find that my real role is to make sure that everyone else has whatever they need to do their jobs properly. For example, I make certain that the wardrobe and makeup ladies can sit where they can clearly see the talent. If Pat or John starts to sweat a little under all the lights, the makeup lady will dart in and put some powder on his head so that it won't shine, and the wardrobe lady will straighten their collars and ties occasionally. She tells me she's never had a producer get her a chair before, but I want everything to be as easy as possible for everyone.

I think we're set. Pat and John each has something to drink (out of shot, of course) and the crew are in place. I take up my position, standing slightly behind and to one side of the camera, then make a final roll call. "Video?" "Ready," comes a voice from somewhere behind all the lights and cables, echoing slightly in the vastness of the studio. "Audio?" "Ready." "Teleprompter?" "Ready," and so on down the line. As they would say at NASA, we have a green board.

"Quiet please, everyone. Roll tape."

"Rolling tape…we have speed."

I've got my script in one hand, one eye on a preview monitor and another on Pat and John themselves. After months of work, it's the moment of truth. Deep breath.

"Action."

Pat: Well, John, it's the beginning of a brand-new NFL season, and our eighteenth year broadcasting together.

John: Yeah, this is the greatest feeling, Pat. Everybody's excited. The teams are here, the fans are here, and it's a whole new beginning. It doesn't get any better than this.

Epilog

Production of Madden NFL Football was transferred out of the Redwood City office of Electronic Arts in the summer of 1999, and with it my job. However, I saw it coming, and on August 2nd I took up a new position as lead game designer for Bullfrog Productions in Guildford, Great Britain… on a product that had nothing whatsoever to do with football.

In February of 2002, Fox Sports refused to renew Pat Summerall's contract, breaking up the famous team that had broadcast together for 21 years. Madden immediately left to join "ABC Monday Night Football" with Al Michaels, where he says he wants to remain for the rest of his career.

Thanksgiving doesn't fall on a Monday, so he's eaten his last six-legged turkey.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like