Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

For some time I was working on an MVC system for Unity, trying to bring some structure in the coding workflow of my projects. As it really helped me, here's a write-down on working with MVC in Unity.

One of the beautiful things about Unity is, that it helps you get startet with your game very fast, even if you have little to no experience in developing games.

But as you get better in coding you sometimes wish to implement stuff, such as for example design patterns, that don’t really work too well with Unity’s built in infrastructure. For some time I was working on an MVC system for Unity, trying to bring some structure in the coding workflow of my projects.

Like I mentioned, MVC doesn’t fit too well in Unity’s environment, especially the often used MonoBehaviour gives me headaches when I’m coding. So why even bother trying to fit MVC in my Unity project? MVC solves one of the problems I struggled a lot with in the last years: Unit tests. As a game grows in size and complexity, it gets harder and harder to test your new stuff or check if the old things still work when you worked on them. Unit tests are a simple way to test calculations and mechanics without the need to start and play your game. The problem with Unity is that it is object oriented and that it is often impossible to test something if those objects don’t get instantiated by the game. Unity’s unit tests allow you to fake your objects to test something, though this functionality is very limited and messy in my eyes.

Whit a MVC design pattern you can separate your calculations and mechanics from the objects in your game and thereby let’s you test them properly.

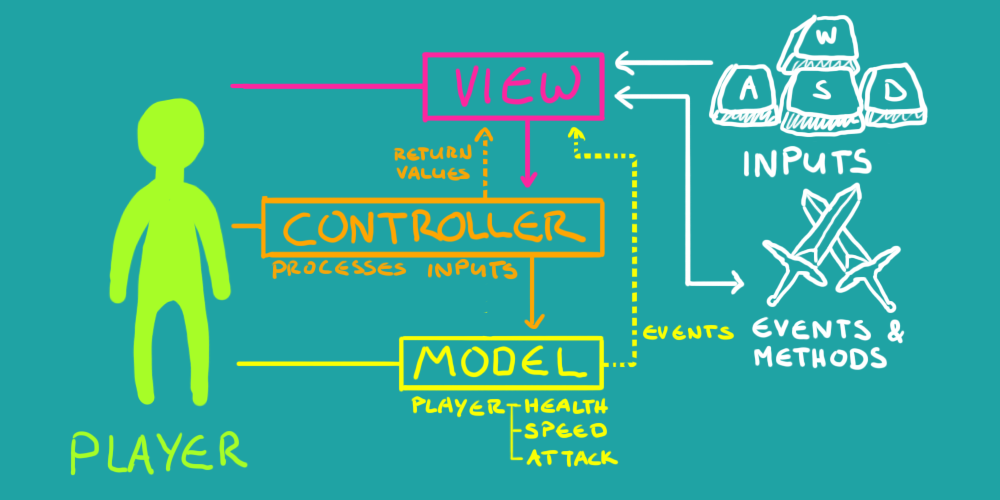

The MVC design pattern splits your software into three major categories: Models, Views and Controllers.

Models store values. In a game related example the model of the player would store their total and current health points, their speed, attack power and so on. Models do not perform any calculations or decisions, nor do they interact with other units or components. They just handle data.

The view is the interface of the MVC trio. It handles inputs and events and is in charge of graphical representation or objects in my concept. The view also is the only part of the MVC unit that communicates with other scripts outside the unit itself.

Finally the Controller is the brain of the unit. It handles information, makes calculations and decisions with it and sends it to the model or returns it to the view.

The communication between the three MVC parts is also strictly regulated. To keep it on a relatively simple level, I designed the view to create the controller and the model. The view needs to have access to both of them, to send inputs to the controller and to check the stored values on the model and for example displaying them.

Both model and controller don’t have references to the view. Thereby the construct stays flexible and modular. To demonstrate the benefits of this, let’s say we want to code a clock. While the controller and model would mostly be the same for every clock – the model stores the current hours, minutes and seconds, while the controller calculates the current time and keeps the clock running – the views can differ. The view could be an analog clock with clock hands and a beautiful baroque clock face, or it could as well be a simple and minimalistic digital design. So with this MVC concept, we could make both clocks with the same model and controller, and simply switch the view for the different designs.

[System.Serializable] public class BaseModel { }

I made three classes, from which all my MVC scripts are inheriting. The model does look very basic, since it only stores values. The only special thing about it is that it is serializable. I did this for one particular reason. I want some values in the model to be accessible from the editor. To make an example: The speed of a car would be stored in its model. But surely you want to tweak it in the editor or make several different cars with the same behavior but a different speed. By making the model serializable, we can access it through the view, which is a MonoBehaviour and will be added to an object.

The model does not have any references, neither to the controller nor to the view or other scripts, we only want it to store values. It is the "dumbest" part of the MVC unit.

public class BaseView <M, C> : MonoBehaviour where M: BaseModel where C: BaseController, new() { public M Model; protected C Controller; public virtual void Awake () { Controller = new C (); Controller.Setup (Model); } }

Here we have the view. It inherits from MonoBehaviour, which allows us to add it to GameObjects. The model is public here, which also is to keep it accessible from the editor. The controller on the other hand is protected, so no external scripts can access it. It is important, that only the view has access to its model and controller, since otherwise we are prone to zombie scripts. If the view gets destroyed, so should its controller and model. If any other scripts do have access to either the controller or the model, they won't be picked up by the garbage collection and you will have instances floating around uncontrolled. So be extra careful here, as the model is public and therefore theoretically accessible from outside our MVC unit.

While the model is created way earlier, the controller gets created and instantly provided with the model in the views Awake method, which is all we need to get our MVC unit up and running.

public class BaseController where M: BaseModel { protected M Model; public virtual void Setup (M model) { Model = model; } }

Last but not least, the controller. It also is quite simple, as it only has one method, to give the controller access to the model. Everything else can be added later, as you need it.

With those base classes set, let's make an example.

[System.Serializable] public class WeaponModel : BaseModel, IWeaponModel { [Header("Shooting")] public float shotCooldown; public bool isSingleShot; public bool isTriggerDown { get; set; } public float NextShotAvailable { get; set; } [Header("Physics")] public float recoil = 0f; }

The model stores all the essential values of the weapon. How long the cooldown is between shots, if the weapon shoots in salves or only single shots, and how much recoil the weapon has.

It also stores values that are important to the controller for its calculations, like if the trigger is currently pressed or at what time the next shot will be available.

To determine, if something belongs in the model, ask yourself the following questions: Is it a method, a decision or a calculation? Is the variable related to an object, is it for example a Transform, GameObject, Rigidbody, AudioClip and so on? If you can answer those questions with no, then the variable most certainly belongs in the model.

public class WeaponController : BaseController, IWeaponController where M: WeaponModel { public bool HasNoCooldown (float currentTime) { if (currentTime >= Model.NextShotAvailable) { Model.NextShotAvailable = currentTime+Model.shotCooldown; return true; } else { return false; } } public bool ShootTrigger (bool isPressed, float currentTime) { bool doShoot = false; if (Model.isSingleShot && isPressed && !Model.isTriggerDown) { if (HasNoCooldown (currentTime)) { doShoot = true; } } else if (!Model.isSingleShot && isPressed) { if (HasNoCooldown (currentTime)) { doShoot = true; } } Model.isTriggerDown = isPressed; return doShoot; } }

The controller calculates, if the weapon is currently able to shoot. It gets all the necessary values from the view, such as the current time. It is very important that the controller does not get Time.time by itself, since we want it to be testable. This way we can give the controller a time value in the unit test, and the controller stays independent from the game.

If there is currently no cooldown, the controller will return true to the view, which will then handle the instantiation of the shot.

Now both of those methods are public. Since HasNoCooldown only gets accessed by ShootTrigger, this might be strange at first glance. But this is for unit testing. I want to test all my controllers methods to be tested, so they all need to be public.

The controller does not have any variables or references. It gets provided with them by the view or can get them from the model.

To decide, if something belongs in the controller, ask yourself these questions: Is it a calculation or decision? Can it be stripped from any objects or variables that only exist if the game is running? Can I simply replace arguments with simple values, such as floats, bools, Vector3s and so on to test the method? If yes, it probably belongs in the controller.

public class WeaponView <M, C> : BaseView<M, C>, IWeaponView where M: WeaponModel where C: WeaponController, new() { [Header("Prefabs")] // -------------------------------------- public Transform shotPrefab; // Rigidbody --------------------------------------- public Rigidbody Rigidbody { get { if (_myRigidbody == null) { GetRigidbody (); } return _myRigidbody; } } private Rigidbody _myRigidbody; // ---------------------------------------------------------- public void Update () { if(Input.GetButtonDown("Shoot")) { ShootTrigger(true); } if(Input.GetButtonUp("Shoot")) { ShootTrigger(false); } } public virtual void ShootTrigger (bool isPressed) { if(Controller.ShootTrigger (isPressed, Time.time)) { Shoot(); } } private void Shoot () { if (Rigidbody != null) { Rigidbody.AddForce (-transform.forward * Model.recoil, ForceMode.Impulse); } InstantiateShot (transform.rotation); } public virtual void InstantiateShot (Quaternion rot) { Transform shot = Instantiate (shotPrefab, transform.position, rot) as Transform; } private void GetRigidbody () { _myRigidbody = GetComponent ()<Rigidbody>; if(_myRigidbody == null) { Debug.LogError("Wanted to get rigidbody on weapon, but couldn't find one on: "+this.gameObject); } } }

To round it up, here we have the view. This example perfectly shows how the view handles input and objects. In its Update method, the view checks if the Shoot button is pressed. If so, it asks the controller if a shot can be instantiated. It will handle the instantiation of the shot, as well as the recoil which will be added to the rigidbody.

The view will not execute any calculations by itself. It only handles the objects with the decisions made by the controller.

To test if something belongs in the view, ask yourself the following questions: Is it an input or a method that will be invoked from outside the MVC unit? Is the variable a reference to an object? Does the method interact with any object? Can the method only be executed on runtime? Does the method interact with something outside the MVC unit? If yes, it belongs in the view.

With the example above you can already see how much cleaner and structured a class can get by splitting it up into those three parts. Not only that, you also can test its core in a mater of several seconds, without having to run the game. Now of course, it can get quite tedious to split every single class into three parts. So I only do it, if unit tests will bring a benefit. For simple scripts, such as for example a MonoBehaviour, that only rotates a wheel or a propeller with a certain speed, I don't need tests, so I don't need MVC. And for smaller classes I like to keep model, view and controller in the same .cs file, to keep the overview.

So knowing when it is beneficial to use the MVC pattern is key here, because it also has some downsides. It probably takes more time to set up, and there is the chance to create zombie instances which might not only affect the performance of your game, but also can produce some ugly bugs.

What I struggled with the most are the generic classes. They are super useful, but they also create some nasty situations from time to time. See my short guide about generic classes for more details about the downsides of generic classes in Unity.

Now there surely are some things that I didn't touch in this post. I'd like to write a small tutorial for unit tests some time in the future. Also please tell me if you are interested in something in particular. I'm writing those posts to share the things I wish somebody explained to me when I was starting to code in Unity, because it sometimes is very hard to figure it out by yourself.

(Note: this is a copy of a blog post on my website.)

Read more about:

BlogsYou May Also Like