Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

Architect: 'And remember - spaces are for people!' Brutalist: 'Those people have sinned and must be punished.'

Architect: and remember - spaces are for people!

Brutalist: those people have sinned and must be punished.

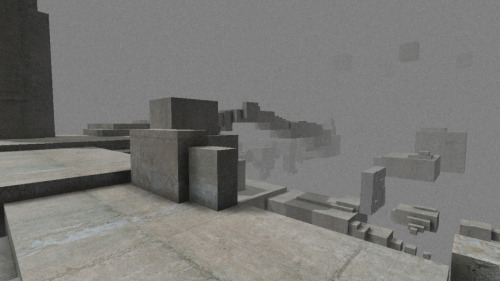

-Fig. 1

I have also created an artefact to accompany this. You can see some screenshots of it, or download it and play it, here: [Link]

Brutalism is a brilliant yet simple aesthetic and architectural style for games by design. Often criticized as being crude, threatening, and lacking decoration or flair, it fits within both the aesthetics of video game art, and within the context of level design and play. There has been recently a revival of the Brutalist movement within the game space in the form of Kairo, NaissanceE, a small mini-game found within Assassin’s Creed: Revelations known as Desmond’s Journey, among others. What makes these games stand out is the atmosphere and sense of wonder they project onto the player, and it is their Brutalist architecture that evokes this feeling. Brutalism works as both an aesthetic decision for games and as a functional one due to its raw, no nonsense construction. Its threatening forms confront the player and add a sense of challenge and accomplishment to level design that few other architectural styles can match.

Brutalist architecture is characterized by harsh, imposing forms, exposed concrete, and often with the silhouette of the moulding material. Buildings of this style are usually large structures, and have exposed functional elements. The Brutalist movement came about during the late 1940s as an expression of atmosphere and seriousness, and as a retaliatory decision to sway away from the architectural styles of the 1930s and early 1940s, and was quickly used to rebuild areas after World War 2 due to its low-cost construction materials and forms (“The Rise and Fall of Brutalist Architecture”, 2011), though it did not have a formal name or style until the middle of the 1950s when the Swedish architect Hans Asplund used ‘The New Brutalism’ to refer to the Villa Goeth (lansstyrelsen, n.d.). It evolved over time into the repeated modular elements, imposing forms, and deliberately raw concrete that characterises it to this day, with architects requesting the pouring of the concrete be done deliberately and coarsely so as to press the building materials into the concrete forms (in situ), creating harsh textures.

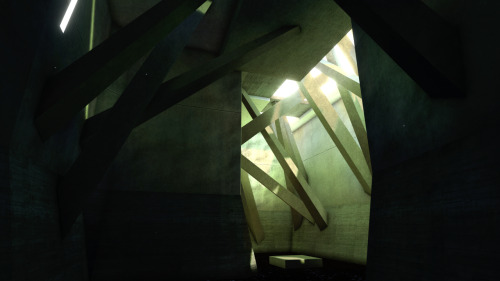

-Fig. 2

Brutalism is closely related to Deconstructivism, Supremism, High-Tech Architecture, and Structural Expressionism, but differs in its lack of external creativity. Instead, Brutalism becomes its own entity instead of expressing an idea or form from its architect. Chris Priestman for Kill Screen said in his piece for brutalism in games: “Brutalism is an idiom for architecture as its own body; it becomes an entity separate from its maker’s touch; it is alive and it is daunting, a creature formed of the city that towers with sharp muscles of rock, a hulking concrete mass.” (Priestman, 2014). The buildings themselves express the ideas through sheer force of presence and imposing will rather than being an outlet for an architect’s ideas.

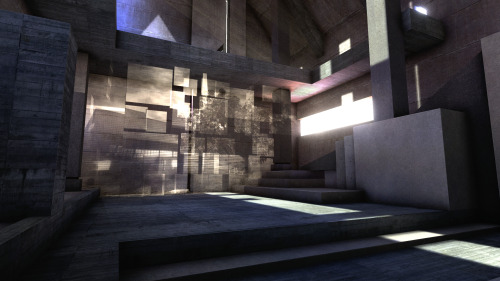

-Fig. 3

A very successful video game called NaissanceE (Limasse Five, 2013) uses this style perfectly to convey its world’s atmosphere and level design to the player. Dan Solberg for Kill Screen describes NaissanceE as “Beguiling, Sketch-Like Beauty.” (Solberg, n.d.). Its shapes and forms are constructed from primitive cubes and cylinders, yet have the character and personality of an entity in and of itself. The simple shapes and clean colouring allow the player to know exactly what to expect from the current environment without any ambiguity regarding what parts of the world are functional elements and what are just for show, yet at the same time has enough mystery in its design to make turning each corner an experience, each new room is different and full of surprises. NaissanceE doesn’t cover its design elements up with high-resolution textures or computationally intensive materials or meshes because it uses those design elements to convey its concepts directly. The core ideas are ingrained directly into the silhouettes and forms of the world of NaissanceE and the player fills the gaps with their experience of it. NaissanceE is narrative Brutalism at its finest; pure visual storytelling without any of the fluff that makes up other more traditional titles.

-Fig. 4

As perhaps an evolution from the pure narrative experience of NaissanceE, Kairo (Locked Door Puzzle, 2013) uses the Brutalist movement to expose its puzzle elements without breaking the lore of the game. Because Kairo features no tutorial sections, speech, text, or really any form of communication other than the audio and visual feedback loop from the game play itself, Kairo almost solely relies on the simplistic, no nonsense language of Brutalist architectural styles to not only tell the player about the world of Kairo, how it came to be, what it all might be for, or where to go next, but also to teach the player in the most perfect way what to do to progress through the game. The exposed elements of Kairo’s puzzle design blend perfectly with the Brutalist designs and harsh shapes, making learning how to play the game synergistic within the game itself: both the player and the avatar being played are trying to understand Kairo, trying to progress further to understand what it is all for. This digital archaeology is framed within an almost Egyptian setting; referencing Neolithic architecture as well as ancient Egyptian, both of which are precursors to the Brutalist movement. Almost as a metaphor for the rediscovery of the ancient Egyptian world by western civilization, Kairo uses harsh lines, simple shapes, and exposed functional elements characteristic of Brutalism to lead the player, entice them into exploring more of the world. The lack of any supporting material or supplementary information makes the world of Kairo expressive in its own right: it is the story.

-Fig. 5

Priestman said “The Pharaohs and ancient Mayan kings understood the commanding might that

Brutalist forms have… these are buildings as monolithic threats,” the architecture of Kairo is expressive and understandable without flair or unnecessary decoration, and expresses instead only its purest intensions: to challenge the player, to provide a difficult puzzle for the player to uncover through exploration and discovery.

The logical culmination of this style of game space narrative symbiosis, and the only game discussed here developed by a large studio: Assassin’s Creed Revelations.

-Fig. 6

Assassin’s Creed: Revelations (Ubisoft, 2011) might not at first be one of the games that comes to mind when discussing Brutalist architecture, but what one needs to understand is the context within which Assassin’s Creed takes place. The first game in the series, titled simply Assassins’ Creed (Ubisoft, 2007), is set in a reality where the main protagonist, Desmond Miles, is abducted and subjected to experimentation through a device called an ‘Animus’ – allowing the person using the device to experience the lives of their ancestors via the manipulation of memories hard coded into the subjects genetic information. In the first game, this device manifested within the core of the game as glitched moments that could be manipulated for a better view of events, and over the series’ releases evolved through different iterations on minor additions and collectibles in the worlds Desmond experiences. In Assassin’s Creed: Revelations, the Animus reaches its apex within the game space. Desmond’s Journey is the name given to the first person exploration / puzzle platforming mini game the player can do as an optional side mission set. Unlocked by finding the requisite number of ‘Data Fragments’ scattered within the simulated world of Constantinople, Desmond’s Journey is by far the most alien thing Ubisoft has ever put into the franchise. Perhaps created as a reference to the First Civilization, a fictional race within the lore of Assassin’s Creed, whose architectural style is similar to Brutalism, and Desmond’s DNA which contains some of the First Civilization’s genetic information, Desmond’s Journey takes the player through his subconscious mind in an attempt within the game to wake him up.

-Fig. 7

A review by Daniel Golding for Crikey entitled ‘The Memory Palace of Desmond Miles’ (Golding, 2012), discusses the architecture of Desmond’s manifest subconscious as reflective of a ‘Mind Palace’ – a thought exercise used to take advantage of the strengths of the human mind to store thoughts and memories using spatial thought patterns. Within the context of the animus, this Mind Palace makes perfect sense: the Animus was designed to explore memories, but Desmond’s Mind Palace is incomplete; his memory of a barn is fractured and expressionistic, and as we delve further into his trauma the memories become more and more obscure, but there’s no doubt that the aesthetic Ubisoft was going for when creating the Mind Palace was Brutalist architecture. The simple forms, the imposing shapes, the repeated structures, the raw textures, it’s definitely Brutalism, but Brutalism as the entity representing the memories of Desmond.

-Fig. 8

A game similar in core concept to that of Desmond’s Journey is Memory of a Broken Dimension (XRA, 2016). MOABD is similar in that the world of the Relics Operating Environment is the character that is interacted with and it is just as fragmented and broken as Desmond’s Journey, but it does so by directly affecting the player’s view of the world. Brutalism is large and monolithic; it doesn’t have to rely so much on directly affecting the play space, it is confident in its design to wait for the player to make the next move. This raw aesthetic that Brutalism embodies is what makes it so fitting for Desmond’s Journey; Desmond’s mind is broken, fractured, and raw. His body is almost dead, having succumbed to the effects of the Animus at the end of the previous instalment in the franchise, leaving his mind nowhere to go, so it retreats into itself; the last fragments of Desmond’s mind yet to break completely are left with their cores exposed in much the same fashion as Brutalism exposes the functional parts of a building. The space of Desmond’s Journey is spatially similar to the memories the Animus is trying to simulate, but it’s running on low power and so the forms it constructs are deliberately simplistic and crude in an attempt to save energy; similar to the choices made by council buildings to use Brutalism as their architectural style as it is cheap and efficient.

-Fig. 9

Now, if these games used another form of architecture to display their content, the experience would be vastly inferior. NaissanceE relies on the forms and structures of Brutalism to convey its sense of wonder and exploration; Kairo uses it as an entity to convey story and seamlessly expose its puzzle elements without making the player feel like they’re being condescended. Desmond’s Journey uses Brutalism as both a narrative device to show the fractured memories of Desmond Miles and as a simulation of the experience Desmond is going through. Brutalism is a perfectly tuned architectural style for meaningful video games because it creates a sense of imposing wonder, it is its own entity in that respect. Its forms and shapes expose its functional design without catering to the weak minded, and this promotes exploration from the player: The forms are harsh and challenging, but the goals are not insurmountable. Brutalism works as a design aesthetic because it does not detract from the core gameplay mechanics or hide the functional elements of play and level design behind fluff and functionless designs. The lack of any supporting shapes and forms also allows games to sit comfortably in an aesthetic style just less than photorealism that is timeless, and so games that use this design often age better than other games attempting to push the boundaries of the technology at the time of their creation, and lets the player use their own imagination to fill the gaps should they so wish without feeling like the game is forcing it on the player.

-Link: http://blog.jhgrace.com/post/133560100012/the-final-result-of-my-brutalist-architecture

·Golding, D. (2012, January 25). The Memory Palace of Desmond Miles [Journalist Article]. Retrieved from: http://blogs.crikey.com.au/game-on/2012/01/25/the-memory-palace-of-desmond-miles/

·Locked door Puzzle. (2013). Kairo [Computer Game]. Bristol, England: Locked door Puzzle

·Lansstyrelsen. (n.d.). Villa Goeth. Retrieved from:www.lansstyrelsen.se%2Fuppsala%2FSv%2Fsamhallsplanering-och-kulturmiljo%2Fbyggnadsvard%2Fbm%2Fvilla-goth%2FPages%2Fdefault.aspx&t=ZDRjMDQ1ZTE1NzY2MDVjYTkzMGM2MzI3MjI5OTNkYjEwNDUxNDY4OCw0N0EwelN6YQ%3D%3D">http://www.lansstyrelsen.se/uppsala/Sv/samhallsplanering-och-kulturmiljo/byggnadsvard/bm/villa-goth/Pages/default.aspx

·Limasse Five. (2013). NaissanceE [Computer Game]. North America: Limasse Five

·Priestman, C. (2014, November 23). Videogames Realize The Full Daunting Potential Of Brutalism [Journalist Article]. Retrieved from: https://killscreen.com/articles/singmetosleep/

·Solberg, D. (n.d.). THE BEGUILING, SKETCH-LIKE BEAUTY OF NAISSANCEE [Journalist Article]. Retrieved from: https://killscreen.com/articles/beguiling-sketch-beauty-naissance/

·The Rise and Fall of Brutalist Architecture. (2011, October 1). Voices of East Anglia [Journalist Article]. Retrieved from:www.voicesofeastanglia.com%2F2011%2F08%2Fthe-rise-and-fall-of-brutalist-architecture.html&t=NmRjMTk1YjU4OWZjMjkzZjkwNDU3MTJmOTY5ZjRiOTQ4MjQyNDZlNSw0N0EwelN6YQ%3D%3D">http://www.voicesofeastanglia.com/2011/08/the-rise-and-fall-of-brutalist-architecture.html

·Ubisoft. (2007). Assassin’s Creed [Computer Game]. Quebec, Canada: Ubisoft

·Ubisoft. (2011). Assassin’s Creed: Revelations [Computer Game]. Quebec, Canada: Ubisoft

·XRA. (2016). Memory of a Broken Dimension [Computer Game]. Steam: Valve

·Fig. 0 - Retrieved from:http://static.zerochan.net/Assassin’s.Creed.Revelations.full.933166.jpg

·Fig. 1 - Retrieved from: http://blog.jhgrace.com/post/132819489317/

·Fig. 2 - Retrieved from: http://cyborgpresident.tumblr.com/post/133293245495/

·Fig. 3 - Retrieved from: https://killscreen.com/articles/beguiling-sketch-beauty-naissance/

·Fig. 4 - Retrieved from: http://blog.jhgrace.com/post/132703047792/

·Fig. 5 - Retrieved from: http://demowebsite5.digipower.vn/Data/imgMedia/banner1-5fa3cb46-424c-4a58-84fa-2b708acc75a4.jpg

·Fig. 6 - Retrieved from: http://blog.jhgrace.com/post/132714554522/

·Fig. 7 - Retrieved from: http://imgur.com/a/bxST2

·Fig. 8 - Retrieved from: http://imgur.com/a/bxST2

·Fig. 9 - Retrieved from: http://imgur.com/a/bxST2

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like