Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Lorenzo Redaelli talks about pandemic effects and trauma for Generation Z youth and how he explored those feelings of broken identity through a boiling hot vacation for three friends.

The IGF (Independent Games Festival) aims to encourage innovation in game development and to recognize independent game developers advancing the medium. Every year, Game Developer sits down with the finalists for the IGF ahead of GDC to explore the themes, design decisions, and tools behind each entry. Game Developer and GDC are sibling organizations under Informa Tech.

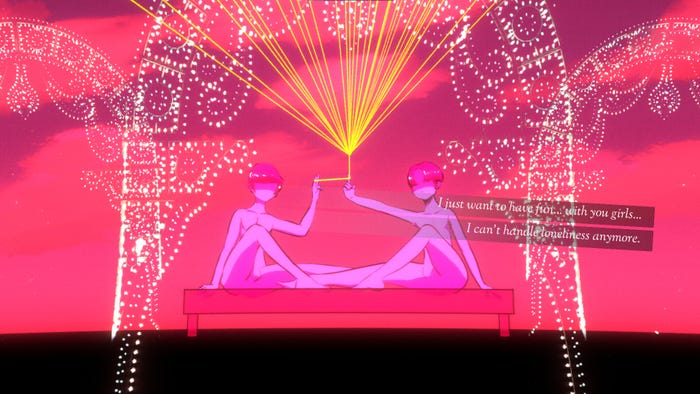

Mediterranea Inferno delves into the lives of three friends in their early twenties, joining them on a steaming summer trip in Southern Italy as they try to recover and reconnect after the pandemic.

Game Developer caught up with Lorenzo Redaelli, the creator behind this multi-IGF award nominated title, to discuss the use of a vibrant, nearly-painful color palette to capture a sensation of fun, but also dangerous, heat, the thoughts that went into the crafting the heady (and sometimes horrifying) mirages that explore the characters’ fears and desires, and what drew him to explore time lost for Generation Z youth during the pandemic and the effects of losing that particular chunk of their lives.

Who are you, and what was your role in developing Mediterranea Inferno?

I'm Lorenzo Redaelli, also known as EYEGUYS, a multidisciplinary artist based in Milan, Italy. I mostly make music and video games. I'm the creator of Mediterranea Inferno. I made all the illustrations, composed the whole soundtrack, wrote the story and I roughly programmed the game. The team at Santa Ragione helped me polish it all, preserving the vision of the project.

What's your background in making games?

This is my second game. My first one, Milky Way Prince - The Vampire Star almost followed the same production style. I guess I'm still in my "background" phase as an author!

Images via Santa Ragione

How did you come up with the concept for Mediterranea Inferno?

I knew I wanted to write something about today's Italy. My grandfather was born and raised in the Puglia region where I spent all my summer holidays with my family since I was little. But every year everything was getting worse, older, and more boring.

I started by considering the most common and widely accepted stereotype about Italy, which is the Italian summer. This stereotype has become a narrative genre that has been explored through various media forms by both Italians and foreigners. However, as a stereotype, it oversimplifies the complexity of the Italian experience and serves as a precedent or common starting point.

The myth of the Italian summer is prevalent among tourists who imagine Italy as a theme park. It is also a myth for Italians, as summer holidays bring back the carefree and prosperous times of the 60s when national production could afford to shut down for a while, and the new bourgeoisie (and not only them) moved to the beaches. The measure of this myth is the pause, the closed bubble, in which everything is brought to the limit of opulence. There is something that needs to be demonstrated in this attitude, which creates expectations, and it is from those expectations that the ritual of the Italian summer is born.

As a writer, I find it interesting to explore the tension between myth and ritual. Something is broken; despite the economic downturn compared to 50 years ago, Italians still tend to take a break from work commitments in August, leading to either a deserted country or a crowded and dysfunctional one. This affects the places themselves, which lose their authenticity and become commercialized, souvenir-cities with high season prices for those seeking genuine human and historical experiences.

So, I understood that the Italian vacation, in its most romantic sense, could become the right microcosm to talk about Italy today—to make a game about the present also by exploiting some allegories.

What development tools were used to build your game?

Mediterranea Inferno is a pretty simple game, technically speaking. It's made with Unity and the different story paths are managed by a plug-in flowchart system. All the drawings are handmade on Photoshop with a Cintiq.

Mediterranea Inferno makes use of a dizzying, near-overwhelming visual style as it follows three friends on a Summer retreat. What drew you to this art style for the game? What mood and feeling were you using it to express in the game?

I wanted to give that hyper-saturated effect you get after staring at the sun or after sunbathing with your eyes closed on a hot summer day. From this comes the idea of using an extremely vivid color palette, which almost hurts the eyes. It's "Inferno" after all, and Hell can be hidden even in Paradise if you're there in the wrong mood or with the wrong people.

I wanted to show the typical elements and situations associated with happy feelings, vacations, and fun, but always with a disturbing undertone—an omen that is impossible to escape from. It also relates to the idea of mirage, a key element of the game—the hallucination given by staying in insolation that blends reality with our inner desire. In the past, people hallucinated oases of freshwater in the torrid desert. Today, even when dying by dehydration, they would see their ideal version of themselves—so unattainable, so refreshing.

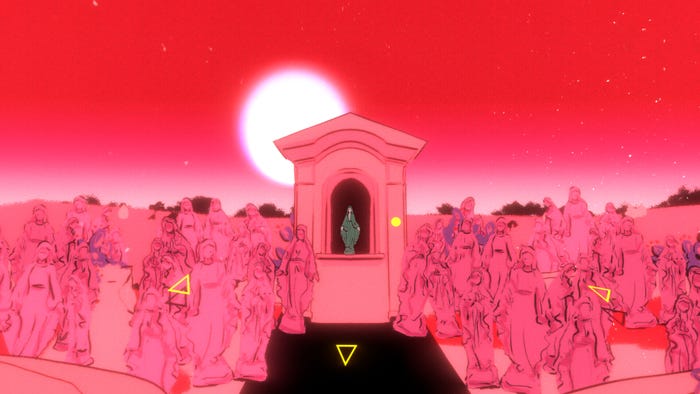

Symbolism through art and religious iconography appears to permeate the visuals of the game. How did these serve the feelings you were hoping to stir with the game? How did they capture the emotions and experiences the friends were going through?

To me, it is impossible to think of Puglia without recalling the religious iconography. Literally, in my great aunt's bedroom, there is a life-size statue of the Virgin Mary that lights up. This is also true for most of the South of Italy, and indeed, for Italy in general. It doesn't matter if we declare ourselves as a secular state, Catholicism is still part of our daily lives, especially passively.

We are constantly surrounded by symbols and ways of thinking that derive from Catholic morality. However, these symbols do not hold the same value for me as a non-believer, nor will they for future generations as they did for the Italians who created them or for those who still believe.

It came naturally to me to explore this game of Catholic elements, especially related to votive production Statuettes, holy cards, holy water stoups, and other items that are part of our religious tradition—I saturated these elements so much that they created a situation where the surplus of symbols paradoxically evoked a hellish scenario. It denounces the weight of all this baggage that we carry around as Italians, which we do not understand, nor do we care to understand.

The characters in the game have a strong desire for redemption, to expel their guilt, and are a reflection of post-COVID society. Very Catholic. The central theme of the narrative is the figure of the martyr. This is what the friends, who belong to Generation Z, are actually after. However, this is also the root cause of all their problems. The world today is highly dysfunctional, and deep down, I guess, what we really want to do is express the suffering it causes us—to show it we want to be pitied. We are not ready to be contradicted even if it means creating more suffering for others and ourselves.

Images via Santa Ragione

Mediterranea Inferno explores a story of three friends making up for lost time—time that was lost at one of the most important times of their young lives. What interested you in exploring this particular kind of loss?

Covid and its endless lockdowns in Italy struck me just as I was moving from being a student to an adult, and a "professional," since my first game had just come out and was receiving numerous nominations and awards around the world, being selected to major events that I could not attend.

I was about 24 years old. I think at that age there’s a voracious need in us to prove that we’ve become the adult we were hoping to become as teens because you are afraid that if you do not immediately take the right path then it will become practically impossible to realize your dreams and your vision. Plus, you feel the pressure to switch to an adult life fearing that all the experiences—ones that you see romanticized in the movies—you have missed will turn into unbearable regrets as you grow up. It may seem exaggerated if you are no longer in that situation, but I remember being totally paralyzed in this dilemma, frozen by the impossibility of taking these experiences that were rightfully mine. And I remember my friends and peers being devoured by this sense of helplessness, frustration, and fear, too.

All of this has led to broken human relationships, brought out a toxic individualism, and some people simply disappeared from each other's lives. So, I wanted to explore this new society that was emerging—these new dynamics. In the end it was not about lost time, but more about the frustration born of the impossibility of meeting our desire. As a writer I wanted to explore all this to intercept the times that would come with the end of the emergency, when we would return to a "normalcy" that could never be the same as before.

How did the story expand outward from this theme of exploring lost time for youths during the pandemic? Can you tell us how this tale shaped itself for you?

After the lost years, each of us felt a personal thirst for a payback. It was quite immediate for me to translate it into a proper competition—a sort of battle royale. I wondered how far certain characters could go if they were given the chance to achieve ultimate personal fulfillment. So, I needed participants, a "not-so-fair" judge, and an inspiring metaphor that truly captured the essence of the competition's supreme goal.

An Italian holiday after restrictions seemed to me the perfect allegory, and we all experienced, at least once, tensions on a holiday with friends, both because everyone wanted to do something different, and for the debated management of the shared "common funds," something I never quite understood. When I was younger, my friends loved using that system to share expenses. I always went along with it even if I still don't get it.

Since I wanted to talk about achieving our most intimate fantasies, I decided that instead of actual money players would manage an "inspiration" budget. Much like the real-world holiday "common funds," the management of the summer coins gives rise to social tensions between the protagonists. This is how the idea of an in-game currency, and the basic mechanics of the game, were born.

At that point, all that was missing was something to buy. I decided to use an approach related to the exploration of desire, which would be maximalist and baroque. I first thought of insolation and then of mirages, but I needed a symbol to represent them. The prickly pear was the perfect choice. It's a forbidden fruit of Catholic inspiration, but also a fruit that requires accurate peeling to be consumed.

Has weaving this story had any effect on you and your own feelings about lost time? Has creating this game had an effect on you throughout development as well?

I honestly don’t think this project had a cathartic effect on me—not as much as Milky Way Prince did. In fact, I could not write a happy ending... I think that similarly to the characters in the game, I also did everything to recover all those experiences living at twice the speed after the restrictions, mostly screwing things up at the beginning.

But working on Mediterranea Inferno has allowed me to order my thoughts about social and political dynamics that I used to accept passively and unconsciously. I like to say that this game did not provide solutions or answers, but it raised problems and contradictions. With the next projects, I would like to offer some solutions.

What thoughts went into creating the game's three main characters? What ideas went into designing their visual styles and personalities?

Crafting the characters served as the game's central focus and initial spark. With Mediterranea Inferno, I embarked on a journey of discovery, dismantling, and insight, with the aim of capturing the essence of Generation Z within the unique context of the present moment.

To chart the course of the project, I needed some key guiding principles. From my perspective, the primary concerns plaguing the older Generation Z cohort revolve around the fear of missing out, narcissism, and disorientation, each intimately tied to the concepts of social connection, influence, and self-definition. Each character embodies one of these themes, and depending on the player's choices, we can witness the intricate interplay and mutual influence of these underlying currents. Ultimately, it becomes clear that they are intertwined facets of the same complex tapestry, complementary in their impact and serving as catalysts for each character's journey.

In 2020, Italian cinema experienced a mini-revival sparked by the release of Call Me by Your Name (directed by Luca Guadagnino) three years prior. It was nearly impossible not to be drawn back into the film's [imagery], and equally fascinating to observe how it resonated with foreign audiences, younger generations, and the general public despite its essayistic nature and deliberate pacing. Guadagnino, no stranger to portraying Italian summers, also explored similar themes in A Bigger Splash (2015). What frustrates me about these films, and Guadagnino's approach in general, is their focus on Americans vacationing in Italy. Often, the Italian characters are depicted as rustic peasants lost in their countryside or farms. I wanted to reclaim those roles a bit.

Nonetheless, there are two elements I genuinely admire and find deeply inspiring in these films, which directly influenced the story and characters of my work. Firstly, the element of boredom, temporal dilation, and the languid pace typical of a summer bubble. These stories often unfold with little plot advancement, instead focusing on character interactions and dialogue. Once the characters are well-defined, they can organically express themselves in various situations. This approach presents a challenge for both the writer and the audience, but it's one I find immensely rewarding.

Secondly, the portrayal of bourgeois characters. Guadagnino's films predominantly feature wealthy, privileged individuals who can afford the luxury of boredom. While his works subtly critique this class, their lifestyle is never truly challenged or disrupted by the realities of life outside their bubble. In contrast, I wanted to explore the opposite. Italy's contemporary crime, as I see it, is pretending to still be a bourgeois nation when most can no longer afford it. Therefore, I chose to make the protagonists of my story three privileged Milanese, individuals reminiscent of those I encountered during my years in Milan's nightlife scene.

Images via Santa Ragione

How did you choose the activities and paths players could take through the game? How did you design what the three friends could do?

I just started thinking about the activities I always did on vacation with my family, especially when I was a kid. I felt like I wanted to recall romantic memories and places but update and desecrate them with disillusioned characters. The places and activities that are proposed by the characters not only reflect their ideal of a perfect vacation but contain a set of requests related to the fear of quitting their comfort zones or their desperate desire for reparations.

Mida does not want to be in crowded places because he fears not being able to receive the right appreciation from crowds in front of his friends and is therefore worried about not maintaining this new untouchable celebrity aura that he has earned and created. Claudio wants to show all his knowledge about those places by showing cultural and historical locations and over-explaining notions and trivia to prove that he belongs to something and that he's got a strong sense of identity. Andrea just wants to hang out in places with a very high probability of having physical and human interactions to prove he can still connect to others.

I think it’s a very interesting way to bring out some narrative elements in a more veiled way and closely linked to the mechanics of the game. Of course, all the places and activities the player can choose are like mystery boxes that might contain the real goal of the game, which is ultimately what Mirages are. And so we can say that each place provides the context, the semantic field, and the pretext for the hallucinatory trip that the character can buy.

What ideas helped shaped the various mirages the characters experience throughout the game? How did you create these journeys into teenage desire, need, and deep personal fear?

As with all addictions, in the beginning, mirages are an accumulation of satisfying, creative, sparking sensory stimuli, but gradually they become gloomy theatrical landscapes—a theme park at closing hours and an empty film set in which it's easy to get lost forever.

While Milky Way Prince explored the theme of idealization, Mediterranea Inferno focuses more on stripping down the protagonists. Initially, the characters in the game are mere personas, playing predefined roles and appearing theatrical. However, as the narrative deepens and complexities arise, they transform into authentic individuals. This shift allows players to delve into their vulnerabilities and wounds, fostering empathy for them even as they reveal their darker sides. It's a descensio ad inferos, and this is where the "Inferno" of the title comes from. Mirages are playgrounds modeled on character psychology, and the more they lose consciousness of themselves and others, the more these become prisons.

I have always been a huge fan of horror movies. While science fiction is the best genre to discuss politics related to society and bodies, horror is the best genre to talk about individual and collective psychology. Therefore, I decided to create a game with horror undertones. When you think of Italy and horror, you immediately think of Dario Argento, Mario Bava, Lucio Fulci, and other directors who are famous for their neon colors, fluorescent blood, satanism, serial killers, and more. I incorporated these elements into the game, especially in the latest chase sequences where I wanted to create an exaggerated atmosphere that is campy and grotesque.

However, this wasn't the starting point. As I've mentioned before, the Italian imagination is infested with a sense of the grandeur of the past. This is what Mark Fisher defines as hauntology, a play on words between ontology and haunting. Shadows, residues, and forms from the past still permeate reality, and we must interact with them. Therefore, I wanted to make it mainly a ghost story, with ghosts representing the collective past and personal fears, anxieties, and expectations of each character.

It wasn't easy to find an aesthetic that resonated with the August holidays and the glossy luster of bourgeois characters while still maintaining the cemetery and gothic nature of the genre. I found the answer in what I believe to be the greatest Italian horror film ever made, Juliet of the Spirits by Fellini (1965). It is a truly unique work that blends ghost stories with psychoanalysis and psychedelia. The ghosts in the film are remnants of the main character's childhood education, her expectations of interpersonal relationships, and the social patterns she came into contact with. The aesthetic of the film is brilliant, mixing jump scares, pale faces with glassy eyes, hooded figures, circus aesthetics, art deco, and colorful Fellini. It's a very different form of horror from what we are used to—very Italian in the positive sense of the term.

How did you create the soundscape for Mediterranea Inferno. What thoughts went into capturing the whirlwind of feelings and the scorching heat of their Italian retreat?

The soundtrack production draws direct inspiration from the vibrant Italian new wave music of the 70s and 80s, the nostalgic allure of vintage Italo Disco, and the timeless charm of Italian Summer Songs that helped shape the myth of the "Italian Summer." This serves as a potent narrative device to prompt political and social introspection on the disillusionment surrounding the failure of the Italian dream.

Throughout the plot, there are numerous nods to iconic Italian songs by luminaries such as Franco Battiato, Matia Bazar, Giuni Russo, and Milva. By choosing sounds, synths, and melodic patterns that come from that world, I wanted to evoke that vintage mood, but it was a difficult solution to handle sometimes because with very synthesized audio elements there is always the risk of falling into that basic, horrible MIDI karaoke effect (which sometimes I’ve kept it, but only when I deliberately needed it to be cheesy!).

There are some organic music features to express the ancient, material, and multicultural soul of the Mediterranean area, like plucked strings, mandolins, wooden percussion, and even the sitar. As the game takes an introspective and gloomy turn, I started to mix all this with a more personal approach that draws from contemporary alternative electronic and IDM music to convey a more hypnotic and psychedelic experience.

Obviously, I had the most fun when it came to crafting music for the game's most unsettling sequences, particularly the climactic chase scenes. Here, a playful and campy approach was adopted to create a chaotic atmosphere that simultaneously unsettles and entices the player to dance amidst the unfolding chaos. Hyperpop elements and exaggerated perreo-like rhythms were incorporated, akin to a summer anthem gone awry.

Through your mixture of visuals, story, and sound, the game feels like it drags players deep into the emotions the characters are feeling—letting them brush up against those moments of overwhelming teenage emotion heightened by global, unrelenting trauma. How did you set out to achieve this deep connection between player and character using all of your tools as an artist?

I have to be completely honest in answering this question and say that it's not something I can intentionally do or control. I believe that the most successful moments in my games are the result of real "meditative" sessions where I can connect with myself on a deeper level, lowering my ego.

That's the only way I can fully embrace the complexity of certain aspects of being human, even the unpleasant ones, and convey my observations to the world through any media. I don't overthink it. I just strive to be authentic.

In the case of Mediterranea Inferno in particular, I think there is a whole dialectic layer of sadism and catharsis, which acts very powerfully on the audience at a traumatic moment like this. Catharsis is an important social function of art, but it seems to be often overlooked these days in favor of a more wholesome approach. I think I’ve experienced at least once all the emotions and thoughts that my vile and horrible characters have in the game, and I know I'm not the only one. Digging through art into our most uncomfortable aspects can really allow us to understand who we are and the world we live in—to develop empathy and compassion, and to build a values scale to survive today's mess and noise.

You May Also Like