Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

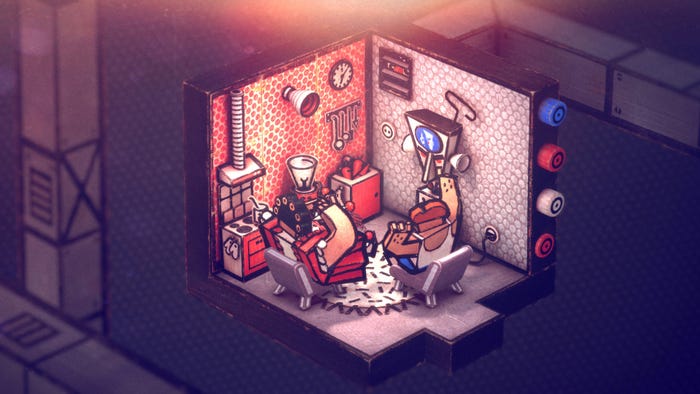

The team at Amanita Design talks about the design processes that went into building a dystopian world entirely out of cardboard.

Phonopolis takes players to a dystopian city made of cardboard, tasking them to explore its hand-crafted world to stop the rise of an authoritarian regime.

Game Developer caught up with the team at Amanita Design, creators of the Excellence in Visual Design-nominated title, to talk about the appeal of working with cardboard to design their machine-filled world, the ideas that went into designing several fashion styles for the various classes of people characters will meet, and what drew them to take this stylized look at an oncoming threat of authoritarianism.

Who are you, and what was your role in developing Phonopolis?

Petr Filipovič: I am one of the three authors of the story, and I worked on the game design with Eva and Oto. I also craft and digitally finalize the paper backdrops, animate and oversee the visual aspect of the game.

Eva Marková: As the game’s artist, I created the initial concept arts, based on which we created assets to be used in the game. With Petr and Oto, I participated in the game’s overall concept.

Oto Dostál: I am more on the technical side of things. I prepared the 3D models for our animators and texture artists, and then I turned their work into actual game assets to be used in the game engine. So, I am kind of like a bridge between the artistic and technical sides.

What's your background in making games?

Filipovič: I used to make games with my brother and my friends way back in high school. Then, I went on to study animated film, which has a lot in common with games.

Marková: Phonopolis is my very first game-making experience. Before that I studied animated films with Petr and Oto.

Dostál: For me it started as a hobby in my high school years. Back then, there were basically no options to study computer games in The Czech Republic.

Images via Amanita Design

How did you come up with the concept for Phonopolis?

Dostál: After graduating from university, we were working as a team on many small animation projects, but we wanted to make something bigger together. So, we played with the idea of a game set in some kind of a dystopian city made of cardboard, paying homage to traditional stop-motion animation. And over time, it crystallized into Phonopolis.

What development tools were used to build your game?

Filipovič: Unity 3D engine, a camera, acrylic paint, cardboard, scalpel, and sandpaper.

Phonopolis features a tactile, craft-like visual style. What thoughts went into its creation? What made this style feel like it suited your adventure game about fighting back against an authoritarian regime?

Marková: From the beginning, we basically wanted to create something tactile to take a break from working with just the computer. Phonopolis is kind of like a miniature model of a dystopian city—The Leader’s vision of an ideal place where everything works the way it’s supposed to under his supervision. Cardboard seemed to be the best option to express that. It’s also quite easy to work with and rather cost-efficient.

Images via Amanita Design

Phonopolis works with stop-motion animation and things made of corrugated fiberboard. What challenges and interesting benefits did this add in development?

Filipovič: We utilized 3D animation with frame-rate lowered to 12 FPS, which is the standard in traditional animated film. The lower FPS paired with animated textures help us achieve the feeling of stop-motion animation, which is necessary to make sure the animated elements fit into the cardboard-built backdrops.

At first, we would take photos of the entire cardboard-built scene and make use of photo sequencing, but for the sake of better interactivity, we ultimately decided to map the photographed assets onto 3D scenes.

Did the game always have this specific visual style? Can you tell us a bit about the iteration process that eventually led to this current look?

Marková: The entire art style was in development for a long time. The first ideas came spontaneously and were much bolder than the final style. We designed and glued entire paper models without having concept art first, which wasn’t very efficient. We were also making lots of preparatory drawings to settle on the stylization and general character of the game.

What ideas went into the design of the city? How did you come up with this charming, yet eerie, place?

Marková: The city is kind of like a tiered cake. It has three different districts—the Workers’ Quarter, Bureaucratic Quarter and Avantgarde Quarter. We let ourselves get inspired by avant-garde, interwar art movements such as constructivism or futurism, which, unfortunately, also served totalitarian regimes. Efforts to bring the art to the masses and influence them through it often ended not too ideally. The totalitarian atmosphere is emphasized by a limited color palette and use of the color red, commonly associated with communism. At the same time, we wanted to incorporate humor and the absurdity of socialism (that we have our own memories of from having grown up in former Czechoslovakia).

Images via Amanita Design

What thoughts went into the costumes and fashion of the characters? How did you design the looks of the regime's clothing versus that of the citizens being taken over? What did you want to express with their fashion styles?

Marková: The costumes and fashion are influenced by the city’s division into several different districts. The Workers’ Quarter is mainly occupied by workers, matrons, and agitators. The Bureaucratic Quarter is filled with clerks and the Avantgarde Quarter has avant-gardists, the highest-ranking members of the society. For costume design, we drew inspiration by a specific ballet from Oscar Schlemmer, an artist belonging to the Bauhaus movement. Our aim was to make a clear line between the “ordinary“ people and the avant-garde “elite“. It’s a quite bold and fun period of fashion, and we really enjoyed digging into it.

How did you design puzzles around this journey through the city? How do you make puzzles around overthrowing a regime and dealing with their forces?

Dostál: There are two main themes in our puzzles: one is that you use the loudspeakers around the city to command the obedient citizens to mindlessly perform determined tasks but in different contexts beneficial to the player—basically “breaking the system” and leading to some absurd situations.

The second principle is that the game world itself is made from cardboard objects, full of little drawers that can be opened, levers that can be pulled, various buttons with many functions… The player is encouraged to play with these paper “mystery boxes'' and to explore their functionality.

What drew you to take this lighthearted look at the grim march of authoritarian regimes? How did you want to explore this frightening thing in your cute game?

Filipovič: Each of these regimes, despite being gloomy and frightening, is also kind of unnatural, rigid, and absurd. This approach is natural and familiar for us thanks to our cultural background and experience with animation. We also feel a connection to the historical memory of Central Europe, which is certainly worth looking into. Phonopolis is thus a sort of advocacy for individuality and diversity against the imposition of a single idea on everyone.

You May Also Like