Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Baked-in lighting, mushy meshes, and high polygon counts are telltale signs of AI-generated work.

Game developers have had mixed reactions to the advance of generative AI in video game development. Some are eager for machine learning-based tools that help solve complex problems, others are tired of being told AI will replace workers or make their lives easier (when it might just make more work).

A wrinkle with the rollout of generative AI tools is the transparency (or lack thereof) of when a game or game asset was made using AI. Hiding this fact can create surprises in the hiring process or publishing side if an asset unexpectedly appears in a game. It can also create difficulties when purchasing 3D assets off of stores like Fab. It's become common knowledge that developers can spot AI-generated 2D art by "looking at the fingers" (or other common cues), but how do you do the same for 3D models?

If modelers making 3D assets with generative AI were required to tag their models as AI-made, it would be easy. But on Fab, they aren't.

Over on Bluesky, veteran 3D artist Liz Edwards answered that question. In a short thread, she broke down common traits in AI-generated 3D models—and how those traits often make said models inferior for general game development usage. She was kind enough to allow Game Developer to recreate her insights to help you learn how to spot the work of machines.

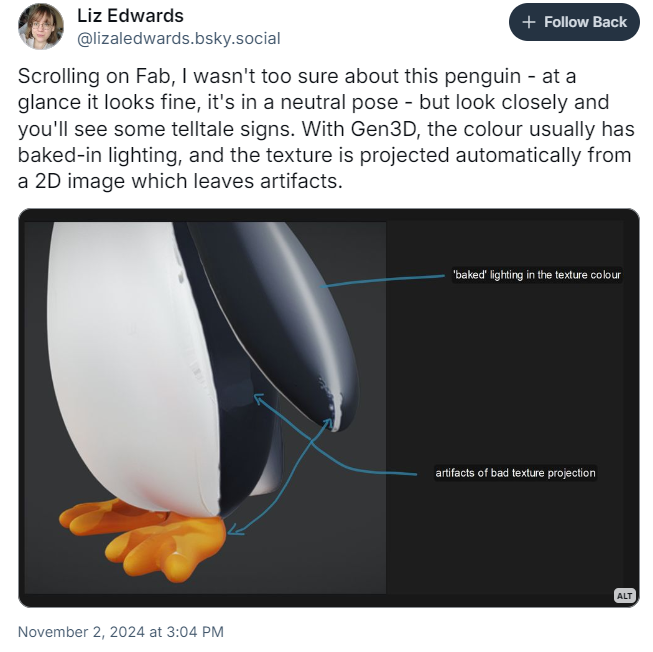

Edwards began by scrutinizing a 3D model of a penguin model she spotted on Fab, which at a first glance, may not seem that odd. Veteran developers may look closer and notice some oddities like the shape of the feet and weird lines on the stomach, but Edwards called out deeper flaws.

The model, she wrote, has "telltale signs" of AI generation. 3D generated models made by AI usually have baked-in lighting, she explained, and the textures are projected from a 2D image. Artifacts from that 2D image remain on the skin.

Image by Liz Edwards via Bluesky

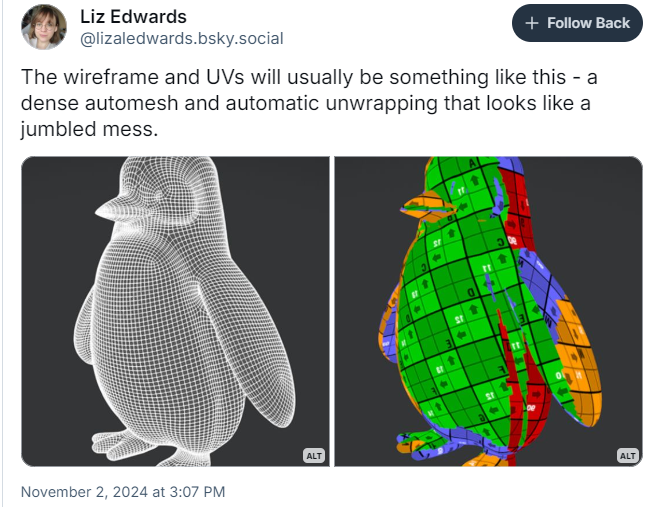

Edwards accessed the model and looked at the wireframe and UV maps, noting that the wireframe looks like a "dense automesh" and the maps were automatically unwrapped, leaving a "jumbled mess" in their wake.

Image by Liz Edwards via Bluesky

She compared it to another penguin model made by "Pinotoon," which possessed more familiar traits, such as a clean UV layout and better-positioned eyeballs and beak.

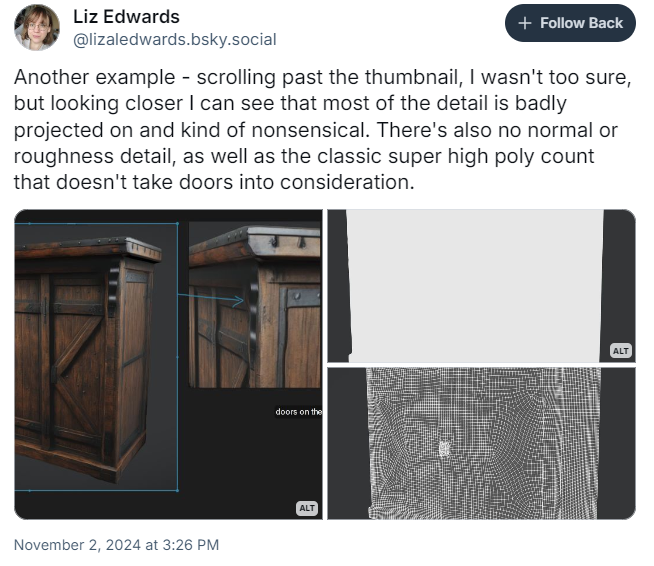

Edwards used another example of a strange cabinet hybrid to illustrate a common trait with 3D generated models: an insanely high polygon count. Elsewhere on Bluesky, she's spotlighted how the creators of genAI 3D models will put objects like crates on the Fab marketplace that have 50,000 triangular polygons, where the average crate in a video game only needs 500 triangular polygons at the very upper end.

Image by Liz Edwards via Bluesky

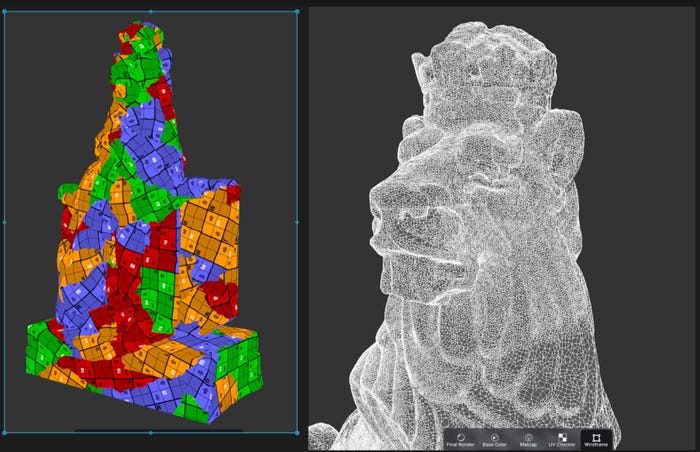

Edwards warned, the traits above alone don't automatically identify a model as being generated by AI tools. For instance, 3D models captured using photogrammetry share the same traits. The difference is that those models have natural textures, are usually free of artifacts, and have coherent, naturalistic details.

Image by Liz Edwards via Bluesky

If you aren't animating a given 3D asset or aren't bothered by its polygon count, you might shrug off a model that looks like it was created with photogrammetry—but beware. As Edwards showed, those models can still have incoherent details that look unsettling or inappropriate when viewed up close.

Image by Liz Edwards via Bluesky

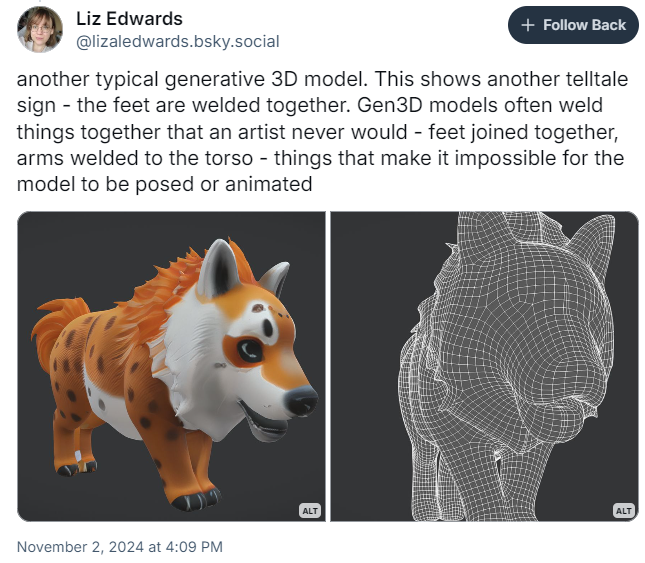

She also explained that meshes on generative AI-made 3D models are "rarely" symmetrical, and are often melded together into "featureless blobs." Those "blobs" often weld together feet or arms, on animals, monsters, and humanoids, making it impossible to pose or animate them.

Image by Liz Edwards via Bluesky

This problem spotlights a major risk of using models that trade quality for efficacy in creation—if the object looks "good enough" but either has too many polygons or is impossible to animate, an object could interfere with the rest of the work a team needs to make a great game.

Should game developers have to make their own Voigt-Kampf tests to identify if visual art is made by generative AI? For now, that would be a "yes." There all kinds of ways that an art asset made with generative AI might slip into your pipeline, and if it's not caught quick, it could cause problems for a team not ready to catch them.

Not all generative AI tech is made with deception in mind. But it's been pointed out that a broad usecase for generative AI is to deceive others, especially when using image, text, or video generation.

A developer in search of a solid penguin model might waste valuable time trying to get this flawed version to work. A recruiter inexperienced in 3D modeling might forward a candidate with AI-generated models if they can't see the machine-made imperfections. For now, all developers can do is arm themselves with the necessary tools and make a judgment call if an AI-generated model fits their needs.

If you need to do your own sorting a little bit faster, make sure to review Edwards' full thread (and other posts about 3D art) over on Bluesky.

You May Also Like