Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

For today's Gamasutra feature, we present our coverage of the second annual Machinima Festival, including panel reports, the winners of the 2006 Mackie Awards, and interviews with two of the most recognized practitioners of the form: This Spartan Life's Chris Burke, and Trash Talk's Matt Dominianni.

Having started out a as fan scene of Quake videos, machinima has evolved into an art form recognized by the game and film community. Call it video game movies or a form of emergent gameplay, machinima is filmmaking using real-time video game visuals in 3D with off-the-shelf software. Because of its accessibility, machinima has become the cheap and popular way to create narratives in 3D environments, which previously would have not been possible without legions of animators or render farms. Machinima’s mainstream exposure includes “Red vs. Blue,” recently featured at Sundance, and South Park “Make Love, Not Warcraft” episode, which was partially animated in machinima.

The second annual Machinima Festival took place on November 4 -5 at The Museum of the Moving Image in Queens, New York. The museum, which archives film and media artifacts, has become a major East Coast resource of digital art. The two-day festival featured panels and workshops on the state and future of machinima, and screenings of the festival entries. Panel topics covered rendering technologies, legal and copyright issues, and artistic content. Special events included a live machinima improv with the Ill Clan, developer workshops, and the Mackies awards ceremony simulcast in Second Life.

The event attracted machinima makers (or 'machinimakers') from around the world. Most are artists, filmmakers, activists, or gamers, or any combination of the above. While many fell into machinima out of necessity, today some are using machinima for its particular game aesthetic, as well as combining it with traditional filmmaking and animation. With in-game software and support from Linden, machinima making is becoming more popular in Second Life as well.

While most machinima works have a reputation of being gamer fan videos and gag humor, the festival's films hoped to challenge that notion, with content spanning fiction, reenactments, talk shows, political advocacy, and experimental pieces.

What follows is Gamasutra's full coverage of the 2006 Machinima Festival, including panel reports, a run-down of the winners of the 2006 Mackie Awards, and interviews with two of the most recognized practitioners of the form, This Spartan Life's Chris Burke, and Trash Talk's Matt Dominianni.

Copyright and propriety are main concerns in the growing field of machinima, especially if creators want to break into mainstream distribution. Creating films from prepackaged games and existing characters is the game industry equivalent of hip hop sampling. While game companies have been slow to respond to machinima, and in most cases have been supportive of machinima, legal use of game properties are still up for debate.

“Will I Get Sued?” explored the legal ramifications of repurposing licensed properties. The host of lawyers offered advice on how machinimators can protect themselves before game companies go the way of the music industry – charge high premiums for the borrowing creative material. The panelists included (moderator) Professor Jennifer Urban of the Intellectual Properties Clinic of the University of Southern California, USC law students Amir Kaltgrad and Charles C. Koole, Fred Von Lohmann of the Electronic Freedom Foundation, and Jon Griggs, a filmmaker. The panel was an informative lesson in digital rights, yet its main flaw was, as noted by the moderator, the lack of presence of game publishers.

Kaltgrad and Koole gave briefings on what artists need to know about intellectual property, such as the life span of copyright and trademark, and the concept of fair use, the most contested term in the culture industry.

Professor Urban then explained the infringements of copyright, which includes anything copied, distributed, performed, displayed, and derivative of owned properties. Parody such as “Red vs. Blue” is permitted, while using a Halo machinima for an Iraq protest film would not. She illustrated the case of trademark protection, Marvel vs. NCsoft, where Marvel sued NCsoft’s over the likeness of Marvel characters and logos (Marvel and NCSoft eventually settled). The group warned creators to read the fine print in End User License Agreements (EULA). Optimistically, the group concluded that no machinima creators had been sued – yet.

The next panelists gave an example of a real case study of machinima artist vs. game publisher. Fred Von Lohmann of Electronic Freedom Foundation posed the question of whether machinima will be an independent art form or the subject of corporate “sharecropping,” where creators will have to beg permission for each use. A veteran defender of digital creator rights, Von Lohmann warned that without artists’ advocacy for machinima, corporate interests will co-opt the medium, and go the way of the music industry – where licensing itself becomes the profitable industry.

Von Lohmann and EFF represented the fourth speaker, Jon Grigg, a filmmaker who had dealt with an unresponsive game company, Valve. Grigg had contacted Valve numerous times to get permission for Counterstrike machinima for his film Deviation, with no response. He needed the permission in order for Atom Films to carry and distribute his work, and for him to be able to make a profit. While Grigg ultimately received permission, Von Lohmann noted that game companies do not have a stance on machinima yet, and it’s up to the machinima community to sway things their way.

Von Lohmann reminded the audience that game companies have been supportive of machinima in the past, but its creators should seek to convince jurors and game companies that machinima does not compete with game sales. Another step creators can take to protect themselves from copyright infringement suits is to closely read the EULAs, and complain if they restrict machinima. Von Lohmann recommended looking at clauses forbidding creative and derivative work, and clauses that force the loser of any court case to assume legal fees of the corporation. Von Lohmann also recommended creators approach the marketing branches of game companies and remind them that machinima can promote sales and the brand.

Much of machinima is for and by gamers, about games or game parodies. But a small contingent is using the medium for provocation and even social change. The panel, “Machinima with Issues" highlighted a few of these works, ranging from reenactment of historical events to culture jamming. The three panelists brought on a lively discussion of art, hacker culture, and politics in machinima. Moderated by curator of the Museum of the Moving Image, Carl Goodman, the panelists included Eddo Stern, an artist known for game installations such as Tekken Torture Tournaments and machinima Vietnam Romance, Chris Burke, creator of the Halo machinima talk show, “This Spartan Life,” and Alex Chan, first time filmmaker and creator of “The French Democracy.” Screenings of the works were followed by the discussion.

Eddo Stern screened “Sheik Attack”, his 1996 work. “Sheik Attack” featured scenes from a strategy wargame, troops into battle, and at the end, the killing of hostages. With its juxtaposition of Israeli guitar folk music and game violence, “Sheik Attack” is jarring but effective. Stern created “Sheik Attack” out of his discontent with modern wargames perpetuating the fantasy of war, commandos, and real-attack situations. He believes wargames desensitize viewers to killing on-screen, in-game, or even in real-life. His goal was to create a scenario (the end killing scene in “Sheik Attack”) that would re-sensitize audiences. Eddo Stern is currently working on a piece on slum lords in Los Angeles called “Landlord Vigilante.”

Chris Burke, the second speaker is the creator of “This Spartan Life,” the popular talk show that takes place inside an Xbox Live Halo 2 game. Burke screened a PSA on net neutrality using Halo machinima. When the piece was made, net neutrality was the most Googled item of the week; TSL was able to attract a huge audience. Burke also noted that the TSL episode on gun control spawned hotly debated message threads on their forum, and was glad to know that 15 year TSL old fans were debating gun control, and more specifically, was happy to find that TSL exposes world and non-gamer issues to a traditional gamer audience.

The third panelist, Alex Chan, presented his timely work, “The French Democracy.” Certainly the speaker with the most agency, Chan, a son of Chinese immigrants created the work from being personally impacted by the violence and ethnic tensions in France. “The French Democracy” is a recreation of volatile events leading up to last summer’s Paris riots. Chan was incensed by the media’s gross misrepresentation of the rioters, who were depicted as monsters. He decided wanted to challenge that notion and tell a story of marginalized, working class North African immigrants of Moroccan and Algerian decent, and depict them as “more human.”

In the film, the rioters are three male Moroccan youth who are assaulted with blatant, unbearable racism. One man is turned away from a job because an employer does not want to hire blacks; another man is beat up strolling with his white girlfriend. The third man is turned down for an apartment because he is black. The men are infuriated by a society that constantly puts them down, and retaliate with Molotov cocktails in the streets. The moderator mentioned that the work paralleled Do The Right Thing, and panelist Burke noted that the work reminded him of the French classic, The Battle of Algiers. “The French Democracy” also cuts back to scene with a white French family gawking at the riot violence on their TV. The film attempted to represent multiple positions in the riots, demonstrating that every side has a rational story.

Chan was a prime example of someone who turned to machinima out of necessity and accessibility. With no filmmaking experience, Chan created the narrative from Lionhead’s Sims style game, The Movies. Without voice actors, the dialogue conveys with subtitles. Chan disseminated “The French Democracy” on the Internet, and since then it’s received global media coverage.

To end the discussion, the moderator asked when machinima becomes a necessity or a choice. While Chan created from necessity and agency, Eddo Stern found that creating machinima content is an improvisational process. He observed that machinima is at the crossroad and will bifurcate – become either a developed fan and hacker culture, and expand as the medium for gamer fan works, or become a co-opted by corporate interests as a commercial aesthetic and style used to sell things.

Best Picture

The Adventures of Bill and John: Danger Attacks at Dawn

KBS Productions

Best Direction

Edge of Remorse

Jason I. Choi

Best Virtual Performance: Puppeteering

Tra5h Ta1k

The ILL Clan

Best Virtual Performance: Custom Animation

Company of Heroes

Relic Studios

Best Voice-Acting Performance

Deviation

Hardlight Films

Edge of Remorse

Best Visual Design

Edge of Remorse

Riot Films

Best Cinematography

The Adventures of Bill and John: Danger Attacks at Dawn

KBS Productions

Best Original Music

Stolen Life

Phillip Johnston

Deviation

Best Sound Design

Deviation

Neil Fazzari, Tom Efinger, John Moros

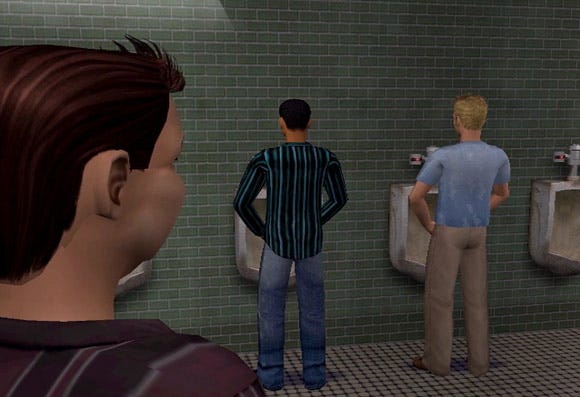

Best Writing

Male Restroom Etiquette

Phil Rice

Best Editing

The Adventures of Bill and John: Danger Attacks at Dawn

Bertrand Le Cabec, Frederic Servant

Male Restroom Etiquette

Best Technical Achievement

Company of Heroes

Relic Studios

Best Commercial Machinima

Silver Bells and Golden Spurs

Eric Call

Best Independent Machinima

The Adventures of Bill and John: Danger Attacks at Dawn

KBS Productions

Best Off-the-Shelf Machinima

Just A Game

Mu Productions

Best Machinima Series

The Fixer

Todd Stallkamp

[A full list of the Mackie Awards nominees as well as winners can be found via the Machinima Festival's official awards site.]

Popular and acclaimed Machinima series “Trash Talk” and “This Spartan Life” combine the live interview format with machinima, swirling the spontaneity of real events into simulated machinima. Not quite video game but not completely Larry King Live, both shows have growing audiences of gamers and the internet community as a whole, and continue to push limits of the possible content of machinima. At the festival, I chatted with Chris Burke of “This Spartan Life” and Matt Dominianni of “Trash Talk” on their reasons for choosing machinima, their audience, and the future of machinima.

GS: How and why did you first start This Spartan Life?

Chris Burke: My co-writer John Keats and I were working together on some sound work. We had seen a bunch of Machinima and were really interested in it as a form. I wanted to do something like an art piece. When I first come up with this idea, I thought it would be something the Rhizome.org people would be interested in and I might post it there; a few artists might think it was kind of cool. I knew about Eddo Stern’s stuff. I had seen Red vs. Blue and wanted to do something different. I had just gotten Halo 2 and Xbox live at that point, and realized [Xbox Live] is really a social space. You’re in there and killing each other, but if you stop killing each other for a second, it’s a social meeting place. You can walk around, you can show people things.

There’s really a whole community there of people who specialize in breaking the game or extending the gameplay into areas that were not intended in the game. I got inspired by that phenomenon. I thought a talk show would be the most rewarding thing you could do there with the way that technology is now. You have the headset, you can communicate with each other verbally. While the avatars are limited in their movement, you can walk about and respond to the 3D environment, do things in it. I thought it would be an interesting to have a combination of a talk shows and documentary, like Bill Moyers, where he interviews someone while he's walking.

GS: What have the responses been for TSL?

CB: We posted TSL on the web in July of 2005. It was received very well from a whole difference audience that we never considered. Several different audiences; one of which was gamers. G4 TV did a story about it, and our site was knocked down by the hits that we got. It got us out there to a lot of people that wouldn’t have seen it. We had this really eclectic demographic. Half of the audience was 15-20 year old gamers, and the other half of the audience were media professionals and academics. It was weird walking that line where we wanted to appeal to both of those sets of people.

Chris Burke (right) interviews Malcolm McLaren (left)

GS: In the piece that screened at the festival, you interview media provocateur Malcolm McLaren. You use your medium to appeal to 15-year-old gamers, a population that might not have been exposed to McLaren. What do gamers think of your content?

CB: To the extent that it’s successful, it’s hard to say. We definitely lose some of the gamers with the stuff we do, and we lose some of the academics with the stuff that’s more game-centric. There’s a lot of Halo in-jokes in the show, gamer in jokes, L33t speak. Some of the academics don’t really get it or aren’t interested in it. We try to balance around the middle. We’ve had a lot of our fans say, "interview this game designer, interview that guy who did the voice for Master Chief in Halo." While we’re very interested in that, I feel like that’s the easy way out. That would be limited what we do.

I want to interview people who have nothing to do with games, or would be fascinated with what you can do in a game. People like Malcolm [McLaren] walk around that game, and was like, “This is weird!” He doesn’t really come across like that in the show but during the interview he would say, “I seem to be lost, the whole place is falling down!”

GS: How and why did you choose to do a talk show like Trash Talk in machinima?

Matt Dominianni: In 1998, myself and the other guys in Ill Clan wanted to get involved with video games. We were also filmmakers. But at that time, making movies was nothing like what it’s like today. There was no such thing as getting a Mac with iMovie. Video editing was very expensive, and there was no way to do simple animation. We were Quake players together and we decided, why not give it a try and see if we can use [Quake] to make a movie.

And this was 1998, where one or two other people had made a machinima movie before us. We made a movie called Apartment Hunting (.mov), and ever since we’ve been continuing with that. We took the character in Quake who, if he’s not holding a gun is holding an axe, and we made him look like a lumberjack. So our characters were Larry and Lenny lumberjack. And basically the show was they walked around one of the Quake maps and talked about how they were getting an apartment there. It went over really well; it’s still on Wired’s Animation Express. Since then we’ve continued with it. We now we do it a little bit more professionally. We do some commercials and things like that, and we perform live in front of an audience.

GS: How do you make Trash Talk? What kind of software and technical constraints you have?

MD: Unlike other machinima filmmakers, we don’t use existing game assets. We create all our own assets and do all our own programming. We’ve created our own virtual television studio with a camera that can teleport to one location to another, and characters can be controlled in real-time. They have facial animation and other gestures, and we actually control them like puppets, and interact with the audience. We’re one of the few people who do Machinima that way.

GS: What software do you use?

MD: We use the Torque game engine by Garage Games. It’s one of the few game engines where, for 100 bucks, you can down get into the source code and change whatever you want. Whereas with some of the other games, you can only make mods. We used to use Quake and Quake 2, but now we use Torque because you can really get in and change things.

GS: Are there copyright issues with Torque?

MD: Basically with Torque, it’s not a game. It’s just a game engine, and every asset we made ourselves. Ill Will is a character we made just for this show. We did that with intellectual property in mind. We don’t want to turn around one day when it’s time to sell DVDs, or time to move on, and suddenly Microsoft owns our characters.

GS: What are the most popular episodes of Trash talk?

MD: We did an episode in which Ill Will takes a vacation in Second Life. That was a funny one because we got to see that crazy sex, S&M, bondage stuff that goes on in Second Life. So that went over well! And our most popular episode was the music video (.mov) we did for Jonathon Colton’s Code Monkey’s song. And that song is up for best original music today.

GS: Who is your audience? Does Trash Talk crossover to non-gamers?

MD: That is a damn good question. I have no idea who my audience is. We have a place you can make comments on our website. We found because we do a talk show on games, a lot of times what will happen is fans of that game will come and comment. Of course, what happens is that the Counterstrike players come, and they’re all a bunch of 13 year olds, who don’t have anything good to say.

But then we did an episode on Red Orchestra, a WWII game. I think most of the players of that game are a lot older, and their comments were written in proper English. They seemed to enjoy the humor. I think we've got a bit of gamer crowd, but it’s an older gamer crowd. And we’re crossing over. The last episode wasn’t on games at all; it was about Youtube. We’re trying to branch out from having it be a gaming talk show to having it be an Internet culture talk show. It just happens to be hosted by a video game character.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like