Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

In this fascinating post-mortem, the designer of Prince of Persia tells us the story of how its iconic cover art oddly played into its ultimate success.

Game Developer Deep Dives are an ongoing series with the goal of shedding light on specific design, art, or technical features within a video game in order to show how seemingly simple, fundamental design decisions aren’t really that simple at all.

Earlier installments cover topics such as how art director Olivier Latouche reimagined the art direction of Foundation, how the creator of the RPG Roadwarden designed its narrative for impact and variance, and how the papercraft-based aesthetic of Paper Cut Mansion came together with the developer calls the Reverse UV method.

In this edition, Jordan Mechner, the designer of the original Prince of Persia game, walks us through the process of conceptualizing its iconic cover, and how that key piece of art unexpectedly contributed to the game's success.

So many video games, films, and music albums I “own” now live in the cloud, and I’m nostalgic for the days when they existed as physical objects on a bookshelf. The tactile quality, size and shape, and cover art of every game box was linked to memories of how I’d acquired it—new, second-hand, or as a gift?—and of hours spent playing.

For a game developer, a shrink-wrapped box that holds the thing we’ve been working on for years brings home the reality that our game is truly done. In the pre-internet 1980s and early 90s, before downloadable updates and patches, shipped meant shipped.

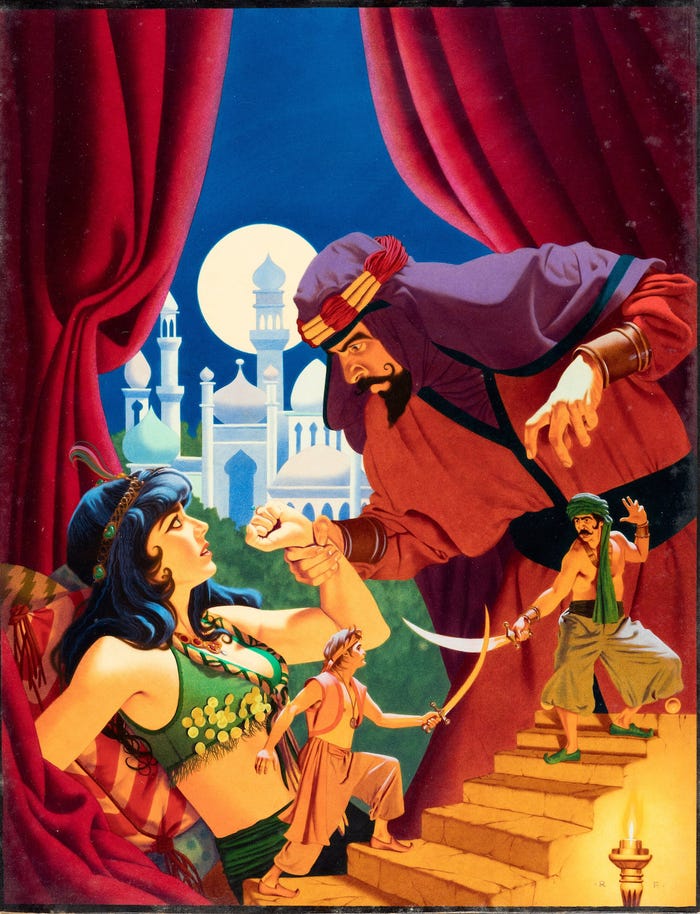

This month, the sale at auction of American painter Robert Florczak’s original artwork for my game Prince of Persia (the Broderbund “red box” edition) triggered memories of the in-house drama surrounding its creation.

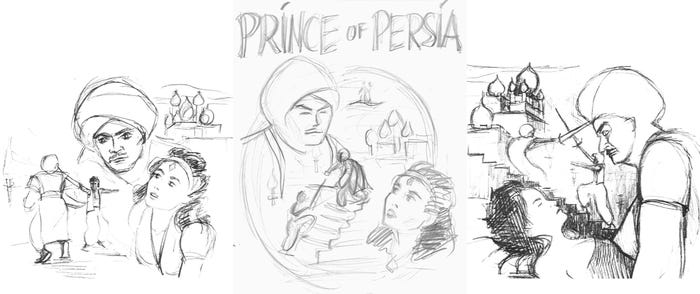

That summer of 1989, I was in the throes of trying to finish and ship Prince of Persia on Apple II, its first platform. I didn’t know if it would be a hit or a flop. Thanks to the journal I kept then (a habit since age 17), I can now recall dates and details I’d have otherwise forgotten—like these pencil sketches I did at the end of April to show Broderbund’s art director my ideas for the package:

Concept sketches for the Prince of Persia box art.

As a rule, a game programmer can expect marketing to receive creative suggestions about package design with about as much delight as a surgeon getting advice from a patient on how to operate. My pitch to do a painting in the spirit of old-school Hollywood swashbuckling film posters like Robin Hood (1938) or Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981) earned a “meh.” But I had a staunch ally in my product manager Brian Eheler. He made sure I was invited to the marketing meeting. Nine color comps were considered; this one won.

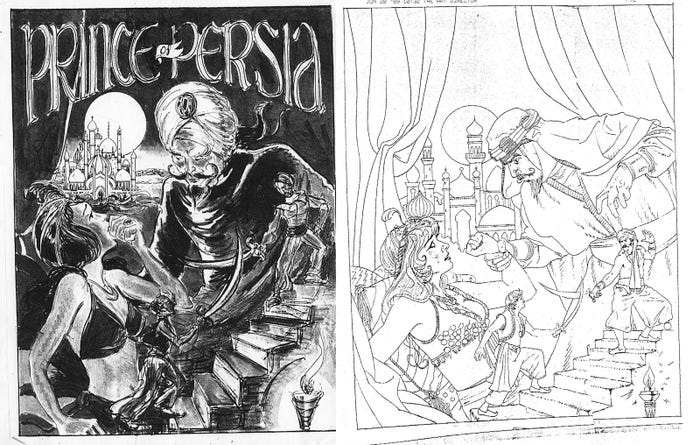

Florczak, our first-choice artist, developed the idea into a detailed sketch (which he sent by fax—this was before e-mail). Things went smoothly until the head of marketing balked at the $5500 price to execute it. My June 7 journal entry records my angst: “After making the rounds and lobbying everyone, I think they’ll OK it, but the whole thing was a really disturbing vote of no confidence in POP.”

While I crunched to ship the game I’d been working on for three years, the general feeling at Broderbund was that it wouldn’t sell. Foolishly, I’d built Prince of Persia on the Apple II, a decade-old machine that even Apple had stopped supporting. My game had fans at the top and bottom of the company but not in the middle, where the actual marketing got done. Apart from Brian, the QA testers who were playing Prince of Persia daily, and Broderbund’s CEO-founder Doug Carlston, few people believed in it.

In the next four weeks, while Florczak painted (his friend Kevin Nealon, an actor and Saturday Night Live comedian, posed for the vizier Jaffar), I fixed bugs, added features, and spent four days in New York with my dad, adding his newly-composed music to the game.

In July, Florczak delivered a lovely painting in 1980s movie-poster style—exactly what Brian and I had hoped for. But seeing the finished work, marketing thought it was too pulp-sexy. Broderbund had started as a game publisher; by 1989, its emphasis had shifted to educational and productivity software like The Print Shop and Carmen Sandiego. Prince of Persia was out of sync with the company’s new family-friendly direction.

Marketing sent the painting back to Florczak for revision. I can imagine with what enthusiasm he duly added a green Persian sports bra to the princess’s decolletage. Personally, I preferred the original; but as I wrote in my journal on July 25: “There are battles you win and battles you lose, and in the big picture, this one is pretty meaningless.”

Then the whole thing nearly crashed at the final hurdle. The box was shown at a company-wide meeting. A group of employees wrote to the CEO, saying the package condoned violence against women and requesting that it be scrapped. Doug gave a balanced two-page reply, acknowledging their valid concerns (“We don’t want Broderbund ever to be seen in such a light”), but defending Jaffar’s threatening gesture as nonetheless appropriate for a villain in a game whose hero could be “impaled, sliced in two, squashed and otherwise discomforted for relatively minor lapses in behavior.” After a tense week of debate, the box was approved.

.jpg/?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

The rest is history... sort of. Prince of Persia shipped on Apple II in September 1989, PC in April 1990, then Amiga. It got rave reviews on all three platforms. And it was a flop.

By July 1990—ten months after launch, three months after the much-anticipated (by me) PC release—fewer than 10,000 red boxes had found their way into gamers’ homes. I recorded in my journal: “POP sold 500 units last month on PC, 48 on Apple. That’s about as dead as can be.” In August, the major chain Electronics Boutique de-listed Prince of Persia due to lack of sales. Chilled, I visited the local mall where my game could no longer be found and was told by a saleswoman: “It’s a great game, but the box was horrible.”

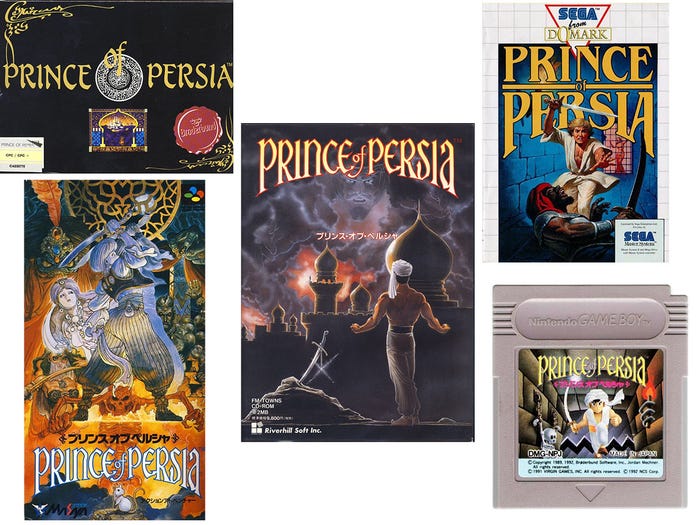

Over the next two years, in a miraculous turnaround that would scarcely be possible today, Prince of Persia was gradually, then suddenly, saved by a confluence of events. First, foreign and console versions, which Broderbund had sublicensed in a dozen different countries on platforms like Nintendo NES, Sega Master System, and NEC 9800, began to ship. There was no coordination; it was the Wild West. Each sublicensee did its own packaging, marketing launch, PR, and distribution, not overseen by Broderbund. The U.S. release flopped, but some of those overseas and console ports became hits.

Some licensees used the red-box artwork, others created their own. For the most part, I didn’t see packages until they shipped. Domark’s box art for the UK Sega version made me wince; I still find it offensive, even by that epoch’s standards. It was too late for them to redo the package, but Brian made them promise never to use it outside the UK. (They promised, but forgot.) At the opposite extreme, I loved Katsuya Terada’s gorgeous illustration for the Japanese Nintendo Super FamiCom version. It’s a fan favorite as well; French book publisher Third Editions used Terada’s artwork for the cover of their deluxe collectors’ edition of my old journals.

The second unanticipated factor that saved Prince of Persia was that the Mac port—which I’d subcontracted to friends at Presage Software—ran two years over schedule. Between 1989 and 1992, Apple released a series of new Mac models: black-and-white and color, with different-sized screens. The Presage team, wanting to take advantage of the latest capabilities, went back to the drawing board and redid the graphics sprites three times. (Each time, I tore my hair out.) By the time the Mac version was finally ready, Prince of Persia’s overseas successes had given Brian and me ammunition to persuade Broderbund marketing that the game had untapped potential. Doug okayed our proposal to combine the Mac release with a PC re-release in a bigger, solidly constructed 1990s-style “candy box,” which we hoped retailers and customers would perceive as denoting a higher-quality product than the flip-top, flimsy-cardboard red box (even though the .exe file on the PC disks hadn’t changed).

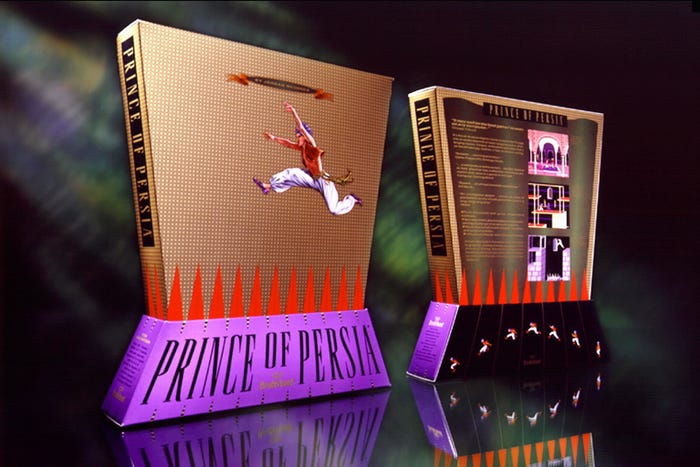

San Francisco designer Hock Yeo, of Wong & Yeo, designed a two-piece candy box with an unusual shape reminiscent of an hourglass. If you’re a PC or Mac gamer who played Prince of Persia in the U.S. in the 1990s, this is the box you most likely remember.

The new box designed for Prince of Persia's re-release on PC and debut on Mac.

The dual Mac-PC release in the oddly-shaped box turned the prince’s fortunes around. A previously untapped cohort of gamers—among them, journalists and editors who used Macs for desktop publishing—were excited to have a game they could play on their new color screens. Prince of Persia became the #1-selling Mac game at a time when most game publishers considered the Mac market too small to bother with. Prince of Persia went from ice-cold to hot on PC as well. Two years after its failed first PC launch, Prince of Persia became a hit.

I was reminded of all this when Florczak’s artwork popped up on an auction website in December. (Doom co-creator John Romero, an Apple II aficionado, spotted it and sent me the link.) The last time I’d seen the full painting unobscured by a title, logo and stickers, it was propped on a desk in Broderbund’s marketing office. It hung for 33 years on Kevin Nealon’s wall, a thank-you from the artist for modeling the Vizier.

Seeing it again, now that its role in the drama of that summer of 1989 is ancient history, I can appreciate the painting as an artwork in its own right. The green stripe still bugs me. But a flaw in a Persian carpet only makes the whole more beautiful. And if there’s one thing video games have taught us, it’s that timing is everything. (The collector whose $63,000 bid won last week's auction would surely agree.) Florczak’s painting joins the ever-expanding collection of diverse physical objects, of all sizes and shapes, that form the tangible record of a video game character’s intangible digital existence.

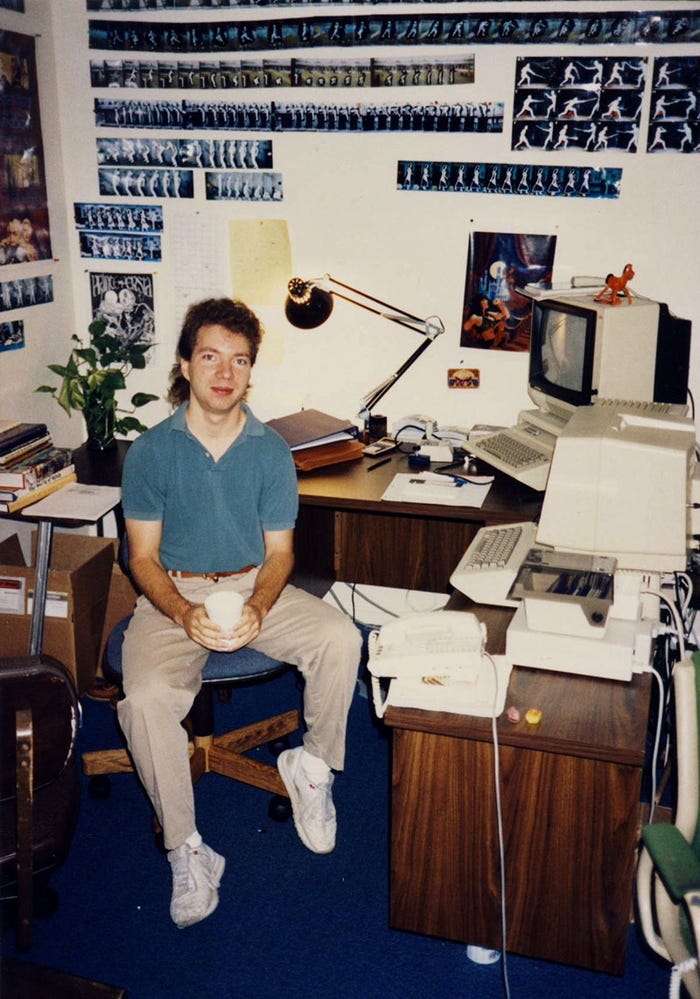

The author, Jordan Mechner, seen at his desk in July 1989. His website at jordanmechner.com includes his blog, current project updates, and a library archive of game-development materials from past projects.

You May Also Like