Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

Elío Ferrán explains the narrative and non-linear dialogue system of King Lucas.

Time before working in the game industry I was in the audiovisual sector; among other things, I studied Cinematography and worked on TV and, there, one of the first things one learns is how to structure a narrative: to create a conflict, to motivate your characters, to throw unsolved questions in order to intrigue the reader/viewer, etc. Mechanisms, in a nutshell, to drive the narrative and make the plot interesting and entertaining because, at last, that's what we want: to entertain. These triggers work exactly in the same way for any kind of story, the problem arises when you jump from a linear media to a non-linear one, such a game, where there is a lot of elements that randomize everything and the user has freedom to alter his path through the story, more or less depending on the game. In King Lucas this is specially remarkable because, even though the level design is predesigned, the disposition of the rooms is random so the path of the user is completely free, thus running into the NPC's in an order out of our control. In this post I'm going to explain how we overcame these challenges in order to make the narrative work out but, to start, we needed...

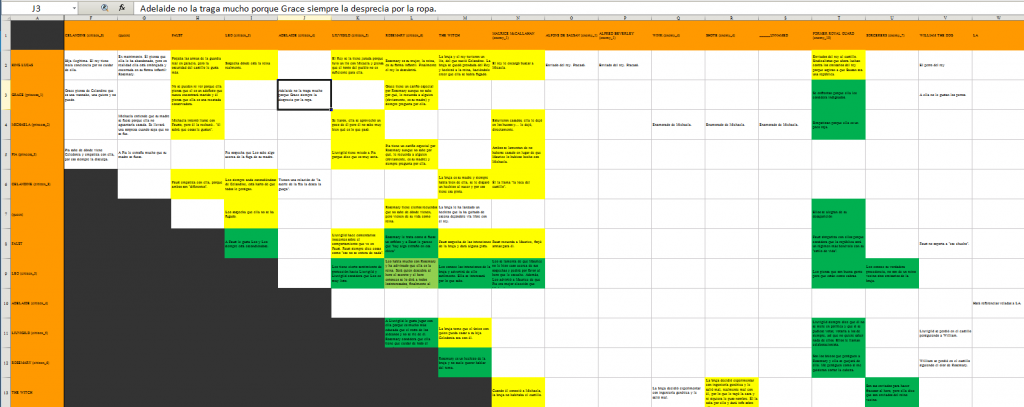

As some of my workmates have told in previous posts, King Lucas was born from the desire to homage some old games and a specific style so, when I began writing the script, the characters were already created, they were basic game design elements: one hero, some princesses to rescue, one king to introduce the hero to the missions, one blacksmith to sell weapons, some enemies, etc... the game design was quite clear and King Lucas would have been playable without any additional storyline but we were sure that adding a deeper narrative was going to add another dimension to the game. In order to get to the story behind King Lucas, first thing was to give personalities to the characters, give them some background that let them interact one each other in a meaningful way. You can't imagine how two characters would talk to each other if you don't know how they think. This way, for example, the blacksmith who was there only to sell weapons became Faust, a former blacksmith of the royal court and sexually ambiguous who decided he felt more confortable in the shadows of the castle of Sausan, or the skeletons that were there just because the game needed enemies became the former royal guard that, tired of so much laboral abuse, became republican rebels to the crown. Of course each personality was designed to cause frictions with the other characters' personalities as well as to be hilarious, to build a comical tone just because it seemed funny to us. In fact, dialogues are peppered with out of context popular culture references that will make more than one user smile. Once the characters were defined, we had to make them interact. What they think of each other? What are they going to say? Do they hate each other, do they love, help each other? What do they know of each other? What do they find out? Are they going to betray anyone? Do they have a past in common or not? We defined this in what we called 'the relationship matrix'.

To focus the writing this way was absolutely intentional. We couldn't forget that, since we were not going to be able to control the path of the user we needed a lot of additional information in addition to the main plot, many pieces of information which once shown, reveal the whole puzzle, the plot: an emergent narrative. When I explain the emergent narrative in King Lucas I like to do it this way:

Imagine a group of people that have read a book and they're in a room talking about it. You step into that room and listen to them, in no particular order you listen to fragments of the story that, in the beginning, make no sense for you but, as you get more details, you start joining the dots and the narrative emerges.

You haven't been told the story in a linear way, as the book is, but in the end you finally understand the plot. The relationship matrix was really usefull for this. There we had the main plot, the secret behind the story of King Lucas, who does reveal it to the hero (to the user), as well as a good bunch of secondary relationships.

Then, when we knew what we wanted to tell, we needed to find how to tell it in a coherent and comprehensive way despite the random trail of the user inside the castle. We could not allow, for example, an NPC #1 spoke about an NPC #2 if this last one haven't appeared yet. We couldn't let any NPC tell a piece of the story dependant upon another information still not told neither. In a nutshell, we shouldn't disorientate users nor spoil the storyline. In order to this, we created several dialogue categories:

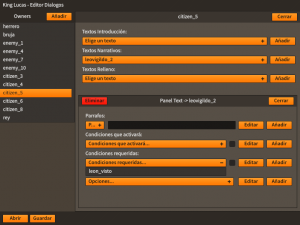

Conditional dialogues: pieces of the script that really drive the story, conditioned to previous pieces to be understood and, in turn, that trigger other conditions so other characters can tell more things.

Filling dialogues: not very relevant information, tips about the game or just jokes which can be understood in themselves. When any character can't reveal relevant information because it still hasn't been triggered, he will talk using these dialogues.

Operative dialogues: sometimes, some NPC's need to give information related to the game, for example the Witch of Sausan who, apart from being a key part of the plot, needs to sell some items.

Once we designed this categorization, the programmers team developed a proprietary software where I could write the script, each dialogue with its unique id, and assign conditions (e.g: if the dialogue id=002 has been shown, then this other dialogue can be shown whenever possible). This way and without losing sight of the relationship matrix as well as taking into account the personality of each character to control the tone of their words, the script was finally written and, in the end, the game chooses what to show at each moment.

It's funny to include references you know not everybody is going to understand; it gives depth and shades to the game. Do you want to discover some of them? Here we go: At some point a character hastens to excuse for something the hero haven't asked for and the hero answers: "excusatio non petita, acusatio manifesta". It's latin, it means that if you put an excuse not required, you're somehow confessing you're guilty. The kingdom where King Lucas takes place is called Sausan. Sausan is a modification of Shawsha, the quechua (old language of the actual Peru) name for the city of Jauja. Jauja is also an imaginary country from the Middle Age where nobody needed to work to live, an imaginary country as Arcadia in the greek mythology. From Arcadia comes the actual term arcade. Join the dots ;-)

Remember King Lucas is available in Steam!

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like