Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

D-Pad Studios claims that their upcoming title Owlboy is "a love letter to pixel art." The team explains how they used art and animation to express character and theme in the game.

The Norwegian studio D-Pad games have been painstakingly crafting the platformer Owlboy for almost a decade. The developers say that the game, due out in November, is "a love letter to pixel art."

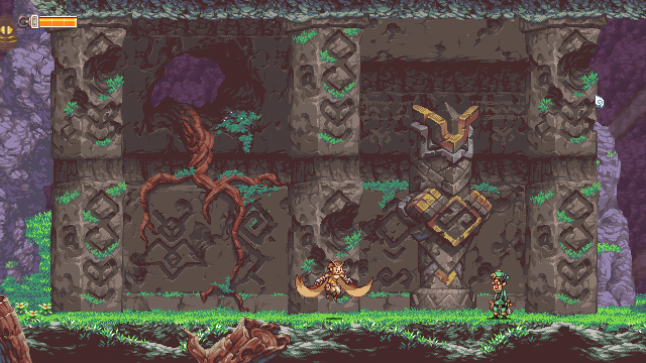

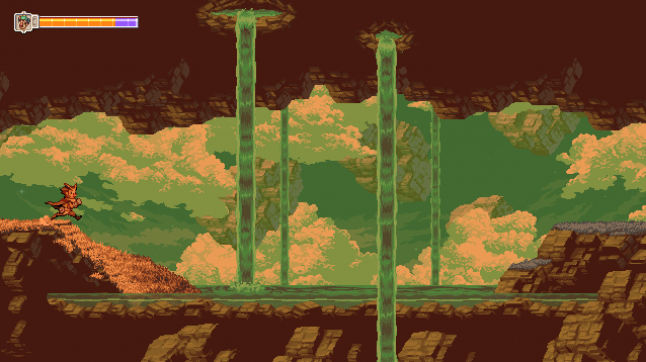

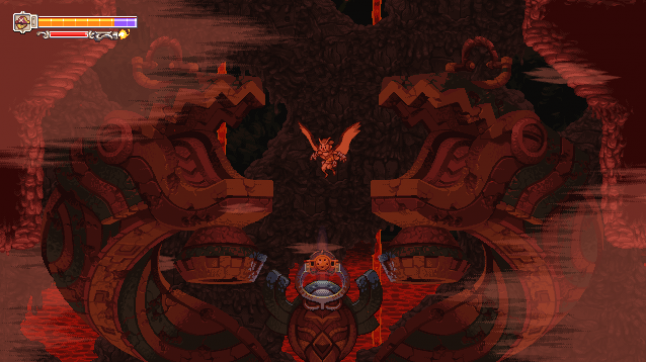

It certainly does have some undeniably beautiful pixel artwork.

But a large part of what makes Owlboy so visually pleasing is how well its characters and locations tie in to each other. Since 2007, the development team at D-pad Studios have been putting a lot of thought into how the people and places in the game connect thematically.

In doing so, they've created unique people in a world that is specifically tied into their history, personalities, and lives. Some developers at D-Pad spoke to Gamasutra about their approach and their goals in crafting the visuals of the game.

"I base everything on shapes and colors so you can easily identify characters," says Simon Andersen, art director at D-Pad Studios and creator of Owlboy. "But as games generally gives you little time to dive into characters lives, having a design trait players can recognize from the surface is essential.

Owlboy stars Otus, a young, mute owl boy in training to become a protector of his village. Clumsy and weak, the boy has great difficulty finishing his training, but must still rise to his destiny when sky pirates attack his town for unknown reasons.

Owlboy stars Otus, a young, mute owl boy in training to become a protector of his village. Clumsy and weak, the boy has great difficulty finishing his training, but must still rise to his destiny when sky pirates attack his town for unknown reasons.

Despite never speaking, Otus has little trouble communicating his feelings and making his personality known due to the efforts Andersen put into making his character expressive without saying a word.

To ensure that all of the actions and expressions tie into the personality Andersen has in mind, he sets up a strong theme for each character as he designs them. By focusing on these themes as he works, it helps tie the character together in his mind, and ensures that their every action and visual feature conveys a little bit about themselves.

"While shape and color language is vital, I feel a clear theme is something that is often overlooked. Themes are fickle, because it's not just about putting some strange clothes on or having a catchphrase." says Andersen. "It's a distilled display of the entire person, put on their sleeve to where you can immediately know something about them. For example, think about how strange it feels when game characters change clothes and hairstyles for example."

Having clear themes and backgrounds for the character in mind ran through every aspect of that character's design. Otus has a hopeful nature, but it's one that he must work hard to maintain as few of the characters around him have a lot of faith in him. Having this background as a theme provided many of the expressions that Otus makes throughout the game.

Otus can look upset or downcast. When his trainer is berating him, his brows droop, and he pulls his wings close around himself. Moments later, he may run into his friend, and his face will light up with a huge smile. Before the player even knows Otus' relationship to this other character, they know he is a friend.

Players can also see Otus' weakness through his actions. When he pulls a heavy object out of the ground, he leans back, arms taut with exertion. He grabs his head when scary things are happening around him or objects are falling nearby.

Having a theme and story for a character may not sound like anything special, but for Andersen, it was a vital part of tying them into the world and creating their story within it. "It may sound very surface level at first, but then you start writing for them. Their thoughts, their relation to the story, their reactions to the plot. Suddenly those surface level traits adds a lot of spice to how you’re fleshing them out as a person."

"The way they should move and react flows pretty naturally, and setting up an expectation for this also allows you to break them, creating twists."

All of Andersen's characters are given a similar treatment, using their looks and movements to tell the story of who they are. The way Otus' friend waves his arms in the air when he finds him after a long absence, the way the smaller bird people lean back and grin with every word, the way the songstress sways as she plays her lute, and the way the sauna man giggles in the hot water all tell the player something about those characters.

They all speak something to the theme Andersen had in his head when he created them, and tell their story before they've spoken a word. The player knows them, and their place in the world, at a glance. "With this method, you end up with a lot of strange, diverse characters, and part of the fun is to create a universe where they all fit." says Andersen.

Part of making the characters feel more alive comes from placing them in a world where they would feel at home. This not only helps create the setting and environments, but also helps feed into a mythology and sense of history that continues to flesh out the characters themselves. The player learns more about them based on the home world they live in.

As such, Andersen tries to keep the themes and characters in mind when he creates a given place for Owlboy. "Sometimes I want to make a landscape that is in my mind, and then you think 'How does this relate to these characters? Does it explain their history somehow? Their motivations?' From there, details start to emerge. Hints towards this underlying story you’ve made in your head."

One of the earlier areas is an overgrown temple. Its presence hints at a buried history for the game's characters, one where they have places that they have long forgotten that will have bearings on future events, and already begins to flesh out more of the characters' backgrounds and stories.

The environments and setting are not just a means to enhance the character stories, though. To make them feel like places where living beings exist, they have to become alive themselves. "The environment is a character and you tell its story with as many subtle or dramatic transitions as possible." says Adrian Bauer, who worked on setting up maps for Owlboy.

Owlboy takes the player to many different settings - some inhabited, others not. Each of these has a different feel that the developers were striving for, with inhabited places demonstrating growth while the uninhabited ones show signs of collapse. "A huge challenge was to show resistance to decay and time. I wanted the temples and dungeons to be struggling with these two things whereas the rest of the world develops as you might expect." says Bauer.

By having these two types of settings pulling in different directions, each tells a little something about the other. The decayed temples tell the player about the world's history, and also, in contrast to the newer settings, show how it has grown from these roots. In contrast, you can see what has been left behind and forgotten by looking at the ruins in comparison to the present. What was there that isn't in the more modern world? Both enhance each other's story.

This unspoken connection also gives the player a greater sense of history, and therefore, a place's believability. The environment's story is fleshed out - it's not just a place for the gameplay to occur, but a place with its own narrative. Even if the player doesn't consciously make that connection, it still subconsciously makes a place feel more real.

"Some of the most fun in creating these worlds is working in this underlying complexity. While players generally only realize a fraction of it, it adds to a sense of wholeness to the place." says Andersen.

And when players start to notice and make their own connections, it gets them more invested in the work themselves. "I like when you clearly see the results of past events but there may not be an agent around to draw conclusions about, only speculation. I think doing so invites the player into the game’s context." says Bauer.

You May Also Like