Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Ten years ago, Maxis released Spore. Former team members look back on the triumphs and challenges in developing one of the most ambitious games of all time.

On September 7th, 2008 Maxis released one of the most ambitious games of its time, Spore.

The single-player sandbox god game was met with a mixture of acclaim and criticism at first after a number of fans were upset it didn’t meet the expectations set in demos shown during Will Wright’s 2005 GDC talk and various E3 showings. It would eventually be recognized as a project that pioneered procedural generation that still has an active player base ten years later.

Over the entire course of development, as the team at Maxis grew from an idea in Will Wright’s head to a team of over 100 developers, every designer that touched some aspect of Spore new it was something incredible. Even if the initial concept would have to change and scale over the course of development.

“The first time I talked to him he said he wanted this to be a game about Drake’s equation. The improbability of our universe,” lead designer Chris Trottier tells me over Skype. “He wanted players to go through all these deep failures so they’d appreciate how incredible it is that we are here. He came off that quickly though, but it was clear how massive he wanted it to be early on.”

Ten years after release members from all aspects of the Spore project were eager to reflect on the challenges, highlights, and overall experience of developing a game as influential as Spore. What follows is a series of excerpts taken from conversations conducted separately with lead designer Chris Trottier, technical artist Kate Compton, lead designer Stone Librande, software engineer Dave Culyba, lead gameplay engineer Dan Moskowitz, and associate producer Guillaume Pierre. (Unfortunately, Will Wright remains elusive...)

Stone Librande: Working on Spore was wonderful. A lot of industry nowadays is making sequels to previous games, so you take an existing game and just add plus one to it. Spore was so different that there wasn’t a lot of models that we had for it. Will had this Powers of Ten vision from starting from a cell and zooming all the out to a galaxy level. It was really like ‘what?’ It wasn’t like any game before it, so the whole team was super excited about it.

Chris Trottier: Spore was an interesting team since it was a hundred people who were used to being the smartest person in the room and when you have people who are used to being brilliant it gets hard for them to say "I’m good with doing whatever works for everyone else."

We had a lot of passionate personalities that created a culture of debate. It was kind of this competitive team, and people were focused on making whatever they were working on the best, which is great -- it's good to have passionate designers, but there was this focus on local excellence over the handshakes that made the game whole.

Dan Moskowitz: I had worked at Sony for five years prior to joining Maxis. I had worked on PlayStation 2 games and that had been my experience up until that point. I worked at a really cool research lab as an undergrad and joining Maxis felt like going back to that a little bit. I remember when I first joined there was an intern whose whole job was to prototype weather patterns, and that was unheard of for a normal video game company. We had someone working on that interstitial sort-of background part of the game because we wanted the weather to have some kind of real simulation behind it.

That feeling of creating creative tools was baked into the culture at Maxis, we were more into things that let you build worlds the way you wanted.

Guillaume Pierre: When I first saw the design document, back in 2003, I was like ‘good luck with that.’ Part of the game was like Pac-Man, part of it was like Diablo, another part was like SimCity. I just thought that there was no way that this game was ever going to come out.

A blurry photo of the Spore team in 2008 (provided by Guillaume Pierre)

Kate Compton: Will’s a huge astronomy buff and the rest of the team had some of the most diverse set of outside interest that I had ever seen in a games team. People didn’t just play video games for their hobbies and work. We had people into biology and physics, we had an ex-nurse -- people just came in with a wad of ideas and since this was a game about everything, everything was in scope. So we had a lot of different prototypes floating around including a very sophisticated particle simulation of oceans to Drake's equation about how life propagates across galaxies.

There was just a lot of stuff like that. The gameplay was always the tricky part. You can have a lot of independently interesting situations but you need to tie them together.

Dave Culyba: I had no prior experience before joining Spore. So one of my takeaways was wow, making games is complicated and frequently messy. It’s not at all this clearly defined plan that you had, it was a powerful lesson in that the scope of the game was big as if we had it all figured out. The demo did a great of presenting this impression of what the game could be, but it barely scratches the surface of what the game needed to be. Figuring all that stuff out like what makes the different parts fun, why would you do this versus that, how do these link together, and how do you even manage to make it work in the first place.

Another interesting aspect was figuring out the scope of the game in terms of schedule. There was this impression that the game was both an infinity away from being done and always just about to ship.

Innovation with a vision -- but what about game design?

Pierre: Chris Hecker and Soren Johnson, who host a podcast together, said something like how Will was more interested in building a game studio and seeing all the different developers interact with each other, like that was his game. He hired a lot of talented people based off their personalities and such, he wanted to see how they interacted and came up with a game.

Librande: We had a really strong vision, but we didn’t have strong game design behind the vision. Like what is the player actually doing from a gamer point of view. If you take a look at the creature editor outside of the rest of the game, it’s just wonderful, it makes you smile. Even today it’s such a fun toy and it’s easy to see why it’s compelling. But once you start think about game systems like what the goal is, how will we make them feel like their leveling up, what’s the skill progression, and things that are traditionally associated with games. A lot of that was just missing.

Compton: It was amazing to see procedural generation used for so many things. The skin generation system, all the procedural mesh generation of the characters, the multiplayer layers animation systems, and there were entire procedural music systems -- there was so much that we tended to even forgot the music guys were back there in a room working on things. We cross-fertilized, and now that I look back on with the scope of all the tools you can use in procedural content generation--we were using all of them. We were using wildly different algorithms and tools behind the spaceship and the creature generators.

I had this idea of having a variation of general stuff. You have some filler, some kind of memorable stuff, and then some hero stuff. Imagine you have a landscape and you have a lot of fairly identical stuff and maybe some of it is mathematically identical, like if you have the same five types of trees that are just rotated and scaled differently. And then you have a couple of things that draw the eye, things that you’ll remember, like a mountain. You have to have a background of different but not interesting things, and then the super interesting memorable stuff.

The uniquely designed Earth planet that Compton created

For example, we had a decent distribution of the generative planets but you definitely began to see the same ones over and over again. I did put in a couple of Easter eggs, like a cubic planet and a perfect model of Earth that I made from USGS data. If you saw either they’d stand out.

Moskowitz: The coolest piece of tech that was in all of Spore was the procedural animation system. That was the system driving the character animation in the editors. It’s what let you build a fully-rigged creature that had nine legs touching the ground and they would all walk naturally.

We worked with the system so as you were building, the creator would react and play animations, like looking at its own arm as you put it on or smiling and making a noise. What you create immediately emotionally responds to you, if it was just static and you were creating it just to look at I don’t think it would be nearly as fun to play with. Each creature would use a certain mouth and have certain sound effects, which led to variation and attachment you would get to your creature. It was also just experimentation, people would rip off the leg just to see what happens and watch the creature wriggle around like a worm and be absolutely delighted by it.

Trottier: One cool thing is that all the prototypes or game modes started as conversations and then moved to us playing aloud by talking. ‘Ok then this happens? Then what do I do when I see such and such?’

It would then lead to us pulling in staplers and cars, and then it was just constantly ‘ok we need more cars, what are the cars doing? There just rumbling down the freeway.’ So many of those kinds of conversations to get to the quick prototype we built in order to prove a level could be all about vehicles.

I remember a prototype we built around the idea of first contact--what was the interesting challenge to winning over the natives. There’s always the scenario where you just blast them away, but then what if your goal changed? What if you were herbivores early on and you had been in this peaceful situation, or you have a species with a ton of babies so they are maternalistic society, and then you come upon another civilization obsessed with building?

We’d picture five or six civilizations and, given that as the blank slate, we’re going to go in and try to make first contact with all of them them. We’d try to figure out what the game was, what did we actually want to do that worked for each of them. We did a bunch of prototyping around crowd behavior and how to read whether they were scared by you or into you, if they’d pull towards you or run away, start cowering and thinking of you as the enemy, and what are the things you actually did to change all that.

It came down to what can we could actually deliver, what’s interesting there. What types of gameplay will survive across civilizations and what types of civilizations would last. It’s like checking your appetite across your belly. I know I want to eat all of it, but what actually fits?

Culyba: An interesting thing about the development of Spore is that the teams were split in different ways. There was creature, tribe, civilization, space, and editors teams, but it was much more of an exploration than I think it appeared at first. It was less about this clear idea of what we wanted the game to be, and more proposals and ideas on where we can take things. It was big concepts that may come together to create things and when you do that you deal with a lot of unknowns.

Librande: It wasn’t really enforced, it was just everyone had so much work they had to do. We all had common tech but everyone had their own set of ways of thinking about things. Like in the civ game you can rotate and control armies around the entire planet, but in the creature game you’re only on one island. The kind of tech you need to play an RTS on a rotating globe is different than what you need RPG-like game on an island. Each team needed different solutions to their problems and everything was going on at the same time, which was why there was a lack of integration between everything.

Moskowitz: On the project there was this constant push and pull between player creativity and the game design of what you wanted to let the player do. For example, we wanted to have the trees to have fruit at different height and the players who make tall creatures could have the luxury of reaching that fruit and become more advanced.

But then there were all these design constraints where you can’t just let players make the creatures' height whatever they want, there has to be a cost for that. It was like, should we put more design elements that were constrictive in the editor, or should we let the player do whatever they want and have the game be more stats-based? We wanted to let the player do whatever they want with the creature, rather than have the things you add to the creature determine the outcome.

Compton: Will Wright’s a big fan of the old BattleBots show they used to have on where people make robots and then pit them against each other. There was a moment when that died when people realized that a wedge bot, kind of an extruded door stop robot, was the ultimate design in robots. It’s really boring and impossible to defeat, it just wears down the other more interesting robots.

If we had went for hard-Darwinism and survival of the fittest with Spore, where you have to be able to design something that needs to survive in this world, we were gonna get a lot of things that are just like wedge bots. All of the weird, strange, wonderful, oddball creatures that were just streaming out of the creature creator-- we didn’t want to tell players that those were bad.

Pierre: We always came back to consequences. Like when you did something in cell game it might affect something else in tribe game or space game. We had to figure out how much of an impact we wanted things to have. Keeping something meaningful without creating an exploit.

Trottier: There was this weird thing where the design team was often arguing for less. As the game goes on and on and on we wish we could afford to have it become exponentially complicated, to give all of these one off cool things meaning as the species got more evolved. But we’re were limited in the amount of stuff we could do.

The argument ended up being for fewer cool things so we could give them all meaning. Not just in the creature game, but throughout their development as a civilizations. You could think of examples for how something would stay meaningful across all the games. If we did claws, they could have a different battle style in tribe game or whatever. You can imagine how a feature would change from level to level but at the end of the day this thing had to be built in less than a decade at a semi-reasonable budget. We had to choose the things that would resonate most across levels, and of course that’s shitty at times.

Librande: I got moved over to the creature game after finishing the cell game and that’s when we started to have discussions about how these games aren’t really lining up well together. They were all done in different silos and the connections between different games were tenuous, sometimes not even thought about at all.

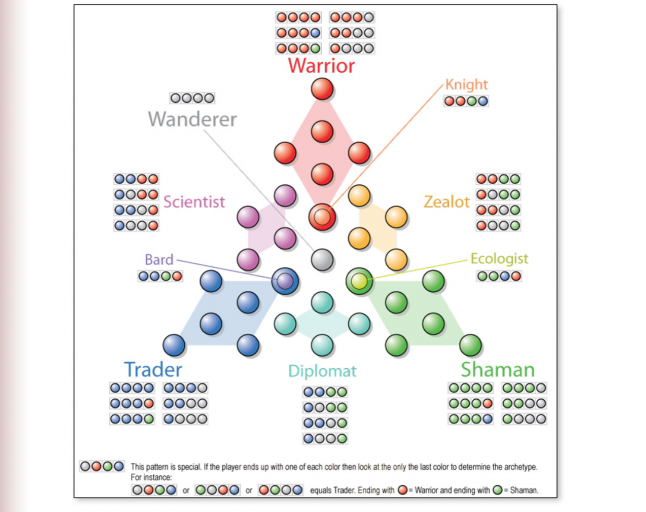

We got an extra year of development time just to work on that problem, to fit all the games into one story. Most people don’t realize this but if you play Spore multiple times through you’ll get different space races with different characteristics. If you play really aggressively throughout the different games you’ll end up with a very aggressive race with a lot of military power. But if you play very peacefully in the beginning, where you’re a vegetarian, you’ll get into space and become what we called a shaman where you could terraform planets and add trees. Most people I’ve talked to don’t realize there are those branching paths, and that’s something we had to do after all the separate games were created instead of at first.

We looked at the outputs of the games in three main ways: aggressively, passive, and then a mixture of both. We would take the outputs of each of those and send them to the next game. So once we got to space we had a history of how you chose to play.

The final iteration of many to create Spore’s branching paths system (provided by Stone Librande)

The final iteration of many to create Spore’s branching paths system (provided by Stone Librande)

Instead of trying to figure out the results of every single combination we decided to create a formula that would just tell you the answer. You start in the middle on the gray dot and if you go one way you become a shaman, the other way a warrior, and down the middle a trader. Mapping out this space was a challenge because it was so big and had so many possibilities.

Culyba: It’s almost like Spore was six years of pre-production from a certain perspective, with all the time going to trying to figure out what this game was going to actually be, as opposed to a well-defined project where we just need to figure out the colors. Innovation is a necessity in gaming, but it’s also risky and unknown. Spore was trying to do way more innovation than people thought it was. If you look at the original pitch, Will talks through different modes in terms of classic games. There’s comfort in the idea that the game will be leveraging gameplay that’s well-known, but the reality is that when you play Spore you don’t think of Pac-Man, Diablo, or Civilization. The gameplay had to be different than what it was inspired by, so Spore was innovating on gameplay more than it thought it was.

Librande: There’s always the bittersweet moment when you ship and then you find out if it holds up against its expectations. I believed that it was a game that would last for a really long time, and if it came out and the reaction isn’t really strong, there was still this feeling of ‘well let’s wait ten years and let’s see.’ Spore has really proven to be this evergreen title.

Compton: The expression I’d like to use is that it’s kind of like a dandelion or the City of Atlantis. Atlantis has all the greatest scientist in the world, mythologically speaking, building pyramids, lasers, or alien technology. It sinks and everyone leaves on boats and each boat heads to a different continent where they continue to build. I think that’s what happened with Spore and why it was important that Spore stopped and that everyone went all over the place. We’ve got Maxoids from Spore working on Oculus, Tilt Brush, Riot, Valve, on dozens of indie projects. There are some of us teaching, like the dandelion can’t make more dandelions until it scatters its seeds to the wind. That happened with Spore.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like