Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Twisted Pixel (Splosion Man, The Maw) creative director Josh Bear delves into the question of what personality contributes to the commercial and artistic success of games in this Game Developer magazine reprint.

[In this article, subtitled "Why Mega Man's Jumping Facial Expression is More Important Than Normal Mapping", which originally appeared in the August 2010 issue of Game Developer magazine, Twisted Pixel (Splosion Man, The Maw) creative director Josh Bear argues that personality brings an important artistic and commercial element to games.]

When I first started out in the industry, I worked under the mantra: "gameplay is king." No matter what, the game needed to be fun and interesting through mechanics alone. I figured I should be able to use a box as my main character and find a way for the player to enjoy controlling that box in an environment.

After several years of designing games and co-founding a company (Twisted Pixel), it became obvious that as great as that sounds, it isn't always the case. Having great gameplay can create a fun experience for players, but without support from other aspects of game creation, that gameplay isn't able to do other things, like create fans or memorable experiences.

Our recent games have received some very kind compliments from fans and the gaming press. Our characters were called unique, and were said to bring personality to our games.

That word, "personality," seems to only be associated with characters most of the time. While I'm not an expert by any means, this article will discuss some reasons why and how personality has worked in our games and others.

I believe that personality isn't just defined by a game's main character; it is something that can be pulled from all aspects of a game. Sometimes this is very meticulously planned out. Other times, it's a complete accident. Taking the time to try to understand how this works has benefited us as a company, and helps our team make sure each of our games is a memorable experience, whether people passionately love it or hate it. Either one is better than being forgotten.

Is personality important? Absolutely. Is it easy to do? Not always. Too many games (especially licensed games and games aimed at children) assume that personality just comes from the license: if the game character looks like the main character from the television show and they share the same voice actor, then personality is covered, right?

It seems like common sense that nobody would think that way, but it happens all the time, even with the coolest characters in the entertainment medium. Games can go so much further when creators take the time to understand how personality works and what it truly means in interactive media.

Character design is a great first place to start figuring out how to infuse personality into your game. Sometimes that design is influenced by limitations of hardware, memory restrictions, and the like. A good example of this is Mario and Luigi from the original Super Mario Bros.

Most people already know the story, but it is said that when Shigeru Miyamoto designed Mario, he gave him a mustache to help separate his nose from his mouth and chin area better. Mario's hat was given to him because hair was more difficult to show with the limited pixel space, and the overalls were there simply to help break up his body so that his arms were more visible. This necessity to create an icon within hardware constraints ended up creating arguably the most memorable character in games today.

Mega Man is another great example of character design working within limitations of hardware. The original Mega Man concept art made it clear that the artist had a specific vision for Mega Man's face, but the limitations of the NES hardware made this impossible to realize. So by just enlarging his eyes and forming his mouth into a big, simple "O" when he jumped, Mega Man was instantly recognizable.

It didn't matter if you liked him or not, it was more about the recognition, and how he stood out as a character with "better" graphics than other NES characters, because they took the limitations of the platform into account.

Designing memorable and lasting characters isn't an easy thing, and there isn't one process that works. You have to find what works best for you and your team. When we design characters at our studio, lead concept artist Brandon Ford will start roughing out a ton of crazy ideas.

After that, the two of us will get together and go over what he started, eliminating elements that we presume won't work for the gameplay style we are going for, or just plain suck. But the most important part of the first step is that there isn't a ton of direction. He just throws down whatever he thinks is cool on paper. That way we aren't limiting ourselves before we even start.

Don't go into character design with obstacles. You may have the perfect vision of what you think the character needs to be, but be open to something totally new and radical replacing your original thoughts.

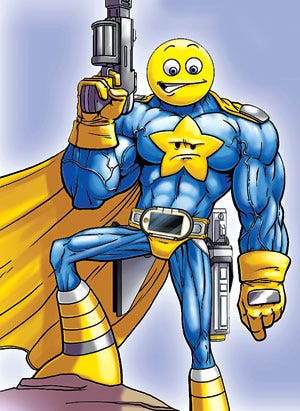

For our character Captain Smiley in our new game Comic Jumper, we designed him to be the most generic character we could think of, since that fit with the story we were trying to tell. Aside from the generic style of it, another reason we decided to go with the smiley-based head is that it would be much easier to show extreme expressions with it through animation than if we went with a human face.

With so many game characters out there (and comic book characters which are the basis of the games) it would be hard to come up with something original enough that we would consider memorable just by looking at a still illustration. So love it or hate it, the smiley face head was instantly recognizable and memorable, and fit into what we were trying to accomplish with the character.

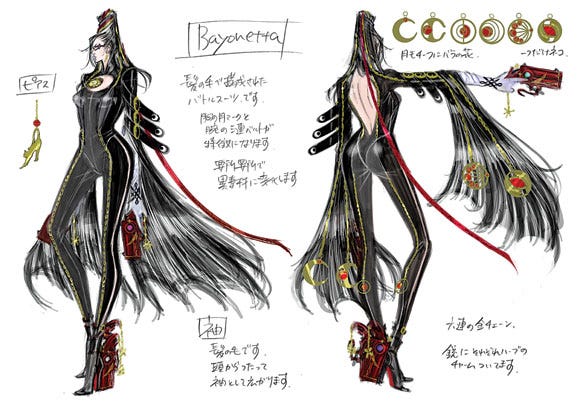

Recent game characters such as Bayonetta and the Big Daddy from BioShock have done a great job of standing out in a sea of game characters that are all competing for the attention of game players. It would have been easy for a character like Bayonetta to be generic (and perhaps some people think she is), but for my money, her over-the-top design keeps her separate from other similar characters.

Her long, crazy hair forms her costume; she holds guns not only with her hands, but on her feet. And then there are those extremely long legs that make her not entirely proportional but aren't pushing it so far that she looks "broken." This is just one example of how a creatively designed character can add a lot of personality to a game.

No matter how awesome your graphics technology is, or how many polys a character has, animation is more important, especially when you want to show personality through characters. There have been a lot of recent games that look amazing in screenshots but fall apart when seen in motion. Most players can recognize bad animation right away, especially if it's coming from a humanoid type character.

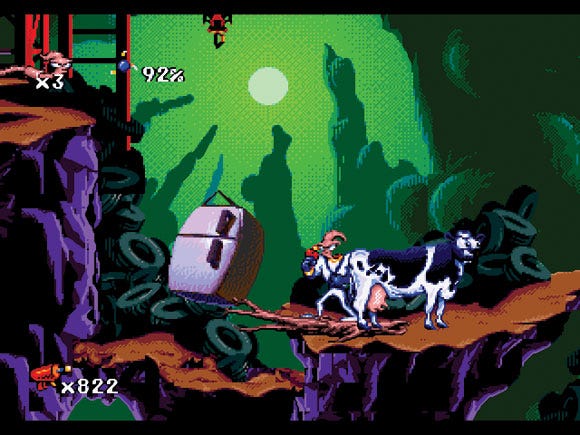

Earthworm Jim, even though it's an older example, continues to be a great way to show how animation defines a character. Jim and all the other characters in the game had a huge amount of detail to their motion, even down to the idle animations. To do this successfully in your own games, work with what you have and take advantage of your strengths.

In our case, we tried to make Splosion Man wacky and crazy through animation to help him stand out from other game characters. We knew early on that we didn't have the manpower to create unique environments for every stage nor a multitude of enemies to go along with them.

By focusing on animations for Splosion Man and the scientist characters, we could pull the player's eye more toward that aspect and less toward what we couldn't do that well at the time.

We used the same tactic on our first game, The Maw (see the December 2008 issue of Game Developer). With only one artist, we had to choose something to focus on, so we decided that the relationship between Frank and Maw would be more interesting and important than the backgrounds and other objects that populated the game.

It would have been great to have a level artist, but that wasn't an important part of getting personality from the end product. Focusing on your strengths, especially if you are a small company, will go a long way. In our case, what we had was a great concept artist and animator, so that's what our game reflected.

Of course, too much animation can be a burden when the animator isn't thinking about how gameplay fits into the equation. There have been a number of games with amazing animation, but where the animator was thinking more in movie terms, and control suffered because the player had to wait for those animations to end. There's a lot of fine-tuning in this process, which is part of what separates beginning animators from the veterans. It usually helps when the animator loves games and gameplay, and doesn't just love animation on its own terms.

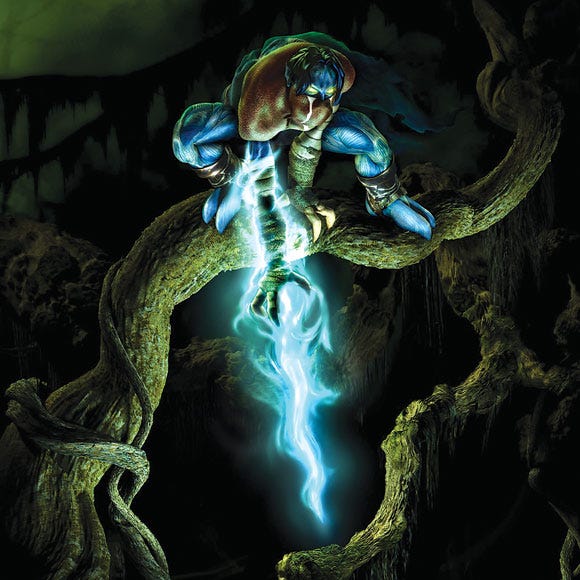

Soul Reaver is an older title that did this well, in addition to taking character design into account. The main character Raziel had a great animation style that found the right balance that made him simultaneously fun and fluid to control.

While it was a departure in visual style from the first game in the Blood Omen series, this ended up working in the team's favor. By enlarging areas of Raziel's body -- like hands and feet -- the developers had an easier time expressing his character through animation. This led to a lot of players remembering Raziel fondly. Animating too much, if it interferes with play, is just as bad as not having enough animation. Knowing the right balance makes all the difference.

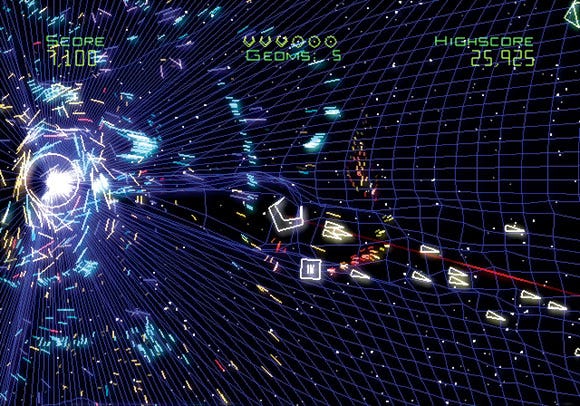

There are a lot of games that ignore the above completely, but manage to have a character all their own. Geometry Wars is a great example of this. Using nothing more than simple shapes with glowing outlines as characters, Geometry Wars still manages to create a sense of personality that separates it from the countless other games that have the exact same gameplay mechanic.

This is because of the way the game combined visual effects and feedback to create what amounts to a gorgeous fireworks display. The tight relationship between the controls, the explosive colors, and gameplay rewards made this game stick in peoples' minds visually.

There's a perfect storm of personality brewing in a game like Katamari Damacy. The soundtrack, strange humor, and simple graphics all help to give it a unique identity. At the time the game came out, though, the thing that stood out the most was the way the game played. Rolling a large ball around and collecting junk, animals, and eventually people was very different from what most players were used to seeing.

While roaming the convention center during E3 when the game made its debut, people would stop and look at the game and wait in line to play it based solely on the gameplay they were seeing. They couldn't even hear the strange music that most people associate with the game.

Don't confuse infusing personality into your gameplay with overcomplicating your gameplay style. Gameplay should supplement and enhance personality, but not be completely determined by it. We decided that we wanted to make a game that only used one action button (not including directional control) to make it as accessible to as many players as possible.

So in Splosion Man, players can make the main character 'splode three times before he must touch the ground or slide down a wall to recharge again. The idea of 'sploding itself is a system that stems from gameplay but is something that people will remember and associate with the character; Splosion Man splodes, that is his thing.

But 'splode is essentially just jump, nothing more, and it's used basically the same as it is in Super Mario Bros. But Splosion Man's "jump" has more personality than most characters in similar games, because it has a unique hook that gives the main character more of a memorable feel and look.

Sound goes a long way toward defining the personality and feel of any game. Let's take the example of Katamari Damacy again. The unexpected vocal-oriented soundtrack defined the tone and humor of the game, and many players associate the music very heavily with the game.

As others have said before, music that plays against expectation can create a more memorable experience. Another good example is the announcer in all of the Mortal Kombat games. Combined with the writing of the characters' lines, the deep voice of the narrator let everyone know that the game had a dark sense of humor and was never taking itself too seriously.

The team eventually took this idea a step further, with the face of lead audio designer Dan Forden coming out of the corner to yell "Toasty!" every so often. To this day, I don't remember any of the combos or moves that I used to repeat over and over in MK2 and MK3, but I will always fondly remember Forden and his shout out.

Having a good sound designer on your team who is open to input is essential. The sound designer should be integrated into the core team, not treated as an outsider.

In Splosion Man, we designed the music tracks out in stems, so that in single-player mode, while the music played in the background, when Splosion Man jumped, it would unveil a new portion of the music track which introduced a guitar layer.

In the four-player multiplayer levels, each Splosion Man had his own musical instrument stem, so that when all Splosion Men were alive and well, the player would hear the entire score for that level. If a Splosion Man died, the other players would subliminally miss that music stem and want to get the player back.

As cool as these ideas were, and even though they were implemented well, they were a failure compared to The Donut Song that was also in the game. Most people who played Splosion Man probably don't even recognize the music stem design at all, or realize how much work was put into it. But The Donut Song, a last-second "why not" addition, is the one musical element that people associate with the game.

Because it adds so much personality, that song did more for the life span of Splosion Man than any well thought out musical stem idea could. Some people love the song, and an equal amount hate it, but either way, it helps define the game's sense of humor. By making sure our sound designer "Chainsaw" knew that he was a valuable part of the team, he was willing to take risks and go out of his way to make the game bigger and better through music and sound design.

In our current game Comic Jumper, we have a theme song for a villain named Brad. This eponymous song has him singing about how awesome he is. In context this works because it fits the ego of the character, but if we had just thrown a song in for the sake of doing it because The Donut Song did well, it would be a disaster. Just randomly throwing stuff in doesn't always work with sound. The personality comes across based on context and how well it fits in with the rest of your world. Games that do this successfully always have a stronger appeal in the personality department.

Environments, when handled with care, can have just as much character as any player-controlled entity. Super Mario Galaxy is an example of this sort of unity of level design and environment art.

As much as Mario adds to the game (along with all the trimmings that make a Super Mario Bros. game what it is), it could be argued that Mario could be replaced with another character, or even a Mii, and the game would still be just as fun and have just as much personality based solely on what the environments bring to the mix, with their unique gravity, spherical nature, and shifting playing fields.

Last year's entry to the Prince of Persia series also did this well, allowing the player to bring the environment back to life through a series of gameplay events. While the levels were typically sparsely populated as far as characters, they were memorable because of layout and the obvious difference between the "dead" and "alive" versions.

Personality shows up in every aspect of games. I could go on to show how personality can come from visual effects, writing, programming, and so forth; but the main point is that personality is good. It makes your game stand out, and gives players something to remember. When people mention how much "personality" something has, they don't necessarily mean the main character of your game. Personality can and should come from collaboration between all disciplines. Then you'll really have something to remember!

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like