Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

From mechs to dinos to a derelict ship, Gamasutra editor-in-chief Kris Graft lays out his top games of 2018.

Kris Graft (@krisgraft) is editor-in-chief, Gamasutra

Hey! It's another annual top games list! I approach these things like a mix-tape that's meant to highlight games that are excellent, but also that give some kind of insight into my own tastes, with the hope that other people might find something they'd enjoy.

I'll be honest, I don't look forward to doing these because they don't come easy. I could tell you right away which games I enjoyed this year, but for me to cogently explain why -- that saps the last ounces of brainpower I have left after an entire year of following the game industry.

Every year in performing this thought exercise, I look back at the list I make, and every year without fail, a theme or two subconsciously arises. This year I gravitated toward two kinds of games:

Ones that had themes of hope and perseverance in the face of difficult situations

Ones that radiated pure joy

Thank you, dear readers, for reading and writing on Gamasutra! Here are the games that brought hope and joy during what felt like a very long year.

List is in alphabetical order.

When Celeste first came out this year, I played it for maybe a half hour, and then stopped. I just wasn't in the mood for yet another hard-as-hell platformer.

It wasn't until I picked it back up at the end of the year when I completely fell in love with it, and appreciated what it was doing. Yes, the game is difficult. But the way the story addresses that difficulty, and emboldens the player to keep climbing, is absolutely brilliant. Celeste shows us that we can be our own worst enemy, but that "enemy" is still an innate part of who we are. And having a friend or two help you realize that along the way never hurts.

Mechanically, it's a simple concept for a player to understand. Jump, dash, and grab. The game masterfully introduces players to the traversal mechanics, then sprinkles in new level design elements where players have to use those basic skills in new ways. It all just feels perfect.

Something about Forza Horizon 4 took me back to when I would get excited about racing games. Even though it's obviously more advanced than the arcade racers that I obsessed over back in the 90s, Forza Horizon 4 was able to capture the sheer joy I'd experience back then.

It wasn't just the weekly change of seasons that were introduced this year or the new online features or the fact that the graphics are good enough to make you weep. The game's main draw is a driving feel that's the best this side of the original Sega Rally (or at least how I remember that game feeling); a feel that I can only describe as "fast and buttery."

Forza Horizon 4 is the culmination of years of fine tuning in that regard. This is a racing game made by people who understand what makes a realistic racing simulator gratifying, and what makes an arcade racer just fun, in equal measure.

Frostpunk is what happens when you take the human condition, turn it into metrics and variables, and plug those into a system meant to test your own personal values. Many games' narratives tell the player about tough decisions and insurmountable odds. Frostpunk instead places the weight of these narrative devices on the shoulders of the player, providing a sense of gravitas and purpose unlike any game I've played. It all feels -- in a literal sense -- meaningful.

The "mechanical" approach to this kind of storytelling makes Frostpunk that much more interesting. There's this idea that "softer" mechanics are a better fit for narrative-focused games, while "harder" mechanics in system-heavy games like Frostpunk are less-equipped to tell a story with as great of impact. Frostpunk masterfully disproves that notion and shows a less-traveled path that game designers should closely examine.

Into the Breach is difficult, and wants to end you. But the game's systems are so readable and transparent, you typically know how the next turn or two are going to shake out. That puts a certain amount of accountability on the player -- you have (nearly) all the information you need, it's just up to you to properly decipher the situation at hand and limit the extra risk that upcoming variables might present.

If I want to get philosophical about it (I guess I do), I found Into the Breach to be about preservation of self for the benefit of others; this is a game more about defense than offense, about keeping yourself alive so you can keep others alive. It's incredibly well-done.

Jurassic World Evolution captured my attention much more effectively than Frontier Developments' earlier console-centric park simulator, Zoo Tycoon. One reason is that caring for a herd of triceratops is, for me personally, more rewarding than cleaning up elephant poop.

Another other reason that Jurassic World Evolution is on this list is because of the satisfaction I got when I was able to get all the game's layered, intersecting systems to play nice. When the brachiosauruses are peacefully grazing in their pens with the perfect amount of water and trees (yes, the forest:water ratio matters), when the orinthomimids have enough peers to where they're socializing, and when the velociraptors aren't running rampant eating visitors, it's a state of pure balance that's supremely satisfying.

That said, when a T-rex gets loose and gulps down a park visitor...that hasn't gotten old yet either.

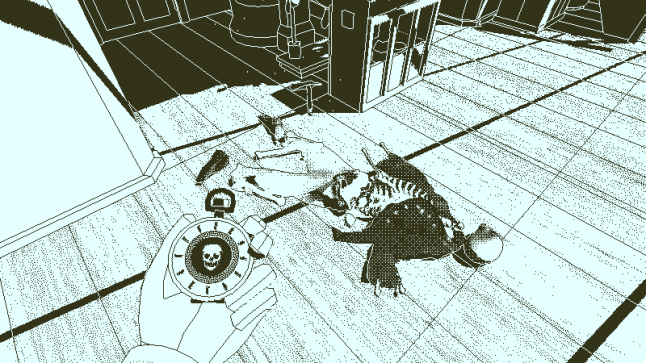

I first played the demo for Lucas Pope's Return of the Obra Dinn a few years ago. Even in its smaller, bite-sized demo form, I immediately fell in love with Macintosh Plus-inspired graphics, and its concept of a mystery-adventure aboard a derelict ship.

The final version of the game impressively scaled up that small demo in which you investigated just a few deaths, turning it into a full-blown whodunnit with dozens of victims. It's a twisted, webbed narrative where the individual deaths of the Obra Dinn's crew are fatefully, and beautifully, intertwined. I can only imagine the sprawling flowcharts and Post-It notes that littered Lucas Pope's workspace.

When playing Return of the Obra Dinn, you can feel the gentle hand of the designer dropping clues like breadcrumbs across the landscape of the narrative, each vignette of gruesome death turning the player into a voyeur of the past. Return of the Obra Dinn is unforgettable.

In the run-up and launch of Tetris Effect, I formed a new pet peeve: people saying things like 'it's just re-skinned Tetris' or 'do we really need another version of Tetris?'

For one, Tetris is a game that humankind will be playing in some shape or form for the next thousands of years, barring any near- to mid-term self-destruction of our species. To say something is "just Tetris" is like saying "just the Ancient Pyramids" or "just the moon landing" or "just penicillin." Tetris is a monumental human achievement.

Ahem ok where were we? Oh yes, Tetris Effect. Yes we do need another version of Tetris -- specifically this version. Tezuya Mizuguchi's take on the game (which was directed by Takashi Ishihara) is surprisingly emotional, bringing together visuals, sound and music, and interactivity together perfectly, with a soulful sincerity unique to Mizuguchi's work.

And don't pass up on this if you don't own PSVR -- while that's a great Tetris Effect experience, the game doesn't lose its beauty on a regular screen. Just turn the lights down, turn the sound up, and play yet another version of Tetris.

You May Also Like