Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

The actors have auditioned and you've made hard choices. In this final part of my series, I go over the last steps for bringing voice acting into your game.

In the first three parts of this series, I covered:

Part 1 – Should you put voice acting into your game?

What level of quality do you need to achieve in the voice acting?

What are the pros/cons of commissioning versus using a casting call?

How much should you expect to pay?

How do you estimate the cost and time of adding voice acting for your game? (I included a “fill in the blanks” spreadsheet tool for your use.)

Part 2 – How to get actors to audition for your game by announcing a casting call?

What preparation is needed before your announcement?

What content should be written to describe your game and the parts in it? (I provided a template document for your use.)

What should a casting call announcement include?

Do you want to accept auditions through email or your Discord server?

How many auditions do you really want?

Where do you post your casting call?

Part 3 – How to coordinate auditions and make a good casting decision?

Mistakes to avoid – changing part descriptions, closing auditions early, giving extra information to some people.

What to do when you aren’t getting enough auditions?

How to judge audio quality of auditions?

How to judge the acting ability of auditions?

In this final part, I’ll describe what you need to do after the auditions are concluded.

The Day After Auditions Close

In Part 1, I bragged about how every actor who had gone through my casting call for The Godkiller - Chapter 1 had sent me their recordings within ten days of being cast. This great outcome with 40 actors was largely due to good luck. The entire group of actors happened to be consistently professional.

But the non-luck reason for fast, reliable delivery from the actors is pace-setting.

Some productions will wait a week after auditions close to announce casting decisions. This is understandable if you want to conduct extra auditions (callbacks) with people on your short list. But ideally, announce casting decisions the next day.

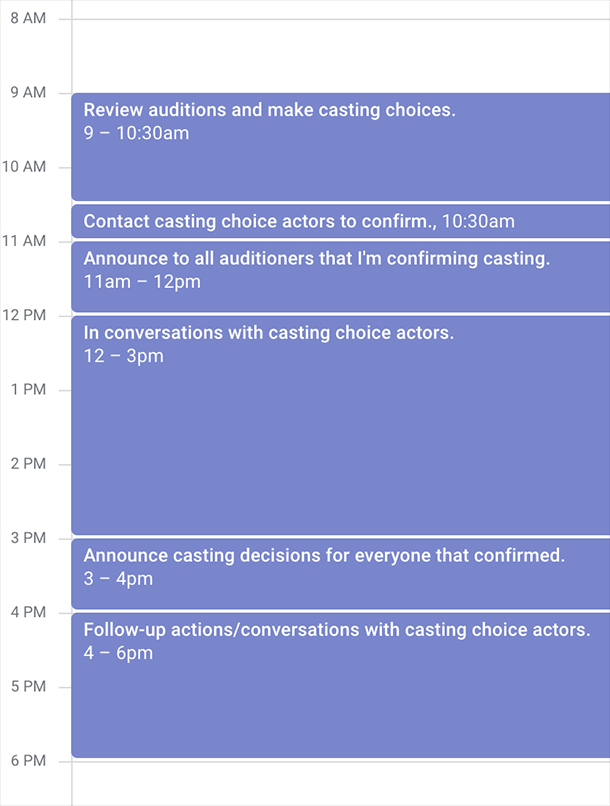

This is what the typical day after auditions close looks like for me.

You’ll notice that the whole day is devoted to the aftermath of auditions. The Day After is definitely a flurry of communication. Then over the next week or so, there will be follow-up actions with cast actors that taper off.

In the morning, I give my full attention to listening to audition recordings to make a casting decision (covered in Part 3).

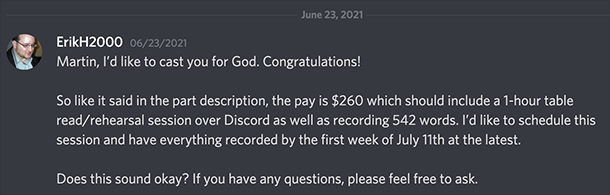

Then I fire off DMs or emails to all of my casting choices to confirm they will do it. For this, I use a little boilerplate customized to each recipient. Here’s an actual Discord DM I sent to Martin Beadle, who was cast for the part of God in my game.

Note the middle paragraph. This is where I remind the actor of the already-described terms for the part. I do this to avoid misunderstandings or attempts by the actor to negotiate beyond earlier terms set.

If I contact for confirmation the day after auditions close, actors almost always confirm within a few hours, and it’s rare that they take longer than 24 hours.

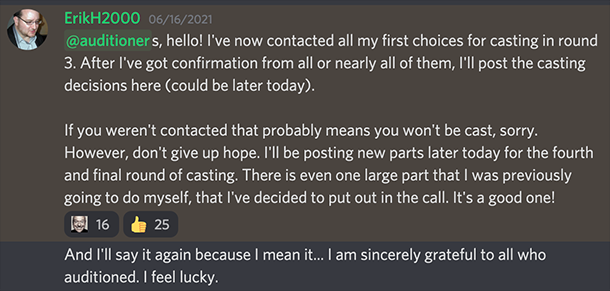

After I’ve sent DMs/emails to all casting choices, I don’t immediately announce casting decisions. It’s possible that some of these castings will fall through. (That’s why I’m confirming.) But I do let all auditioners know that I’ve made these contacts. Here’s a real post.

Why not just wait to post until all my casting choices are confirmed?

There’s a bunch of auditioners still wondering if they got a part – most of them will be not be cast. The kindest thing is to promptly let them know they were unsuccessful. Also, if there’s anyone who has a negative reaction to not being cast, I kind of want them to peel off early so that the community energy stays lovely. Finally, this extra message helps set a faster pace. It communicates that I am actively working on the project and trying to move things along to completion.

Throughout this article, I’ll be advocating many things that move the process along faster. You have more attention, context, and energy from the actors if you move quick. On the other hand, if you drag out the casting decision for a week, actors will mentally drift away from your project and take longer to perform all the little tasks leading up to delivery of their speech recordings for your game. It’s good for everyone involved to keep a fast pace.

In the afternoon, I usually have all casting choices confirmed as actors reply back to me. But sometimes there are one or two I’m still waiting on. I prefer to post casting decisions at that point and just note any straggler as “to be confirmed” without specifying the not-yet-confirmed actor’s name.

Then for the rest of the day, there’s a bunch of follow-up actions and communications with the actors. I’ll go into the follow-up actions below, but it’s stuff like having actors sign release agreements and paying them.

And then there is a terrifyingly transparent thing that I’m proposing you do…

Describe How You Made Your Casting Decisions

While it’s fresh in your mind, say how you made your decisions. And give that information to all auditioners. Writing this casting recap is optional. But I’ve heard such positive feedback from actors on the recaps I’ve written. I really think you should do it.

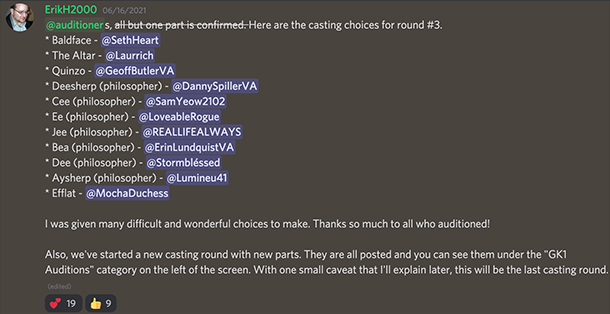

Here is one I wrote for a casting round of The Godkiller - Chapter 1.

The actors are pretending to be some silly character in your game. And after doing this free work, most of them will still not get a part. If you’ve handled this as a public audition, the actors will have shared their personal abilities and flaws with their peers. Step into the light with the actors and share some portion of their vulnerability. Give them insight into how you, a potential client, think.

At the mid-tier level, (discussed in Part 1) many of the auditioning actors will be struggling to figure out not just their craft, but what makes the difference between getting a part or not. Most of the productions they audition for will be black boxes that yield no hints. But yours can be different! Even if your reasons for casting aren’t that great, they are still a valid sample of the voice acting marketplace. Describing how you arrived at your decisions gives actors useful information.

Here are my guidelines for writing a casting recap:

Don’t give advice or coaching. Confine the recap to a summary of your thought process.

Never talk about reasons for rejecting a single actors’ audition or discuss reasons that would identify specific actors implicitly.

But do talk about general reasons for rejecting auditions. In the example recap above, I mentioned that many of the younger-sounding voices for a part didn’t match my image of how the character should sound.

Praising individual actors should mostly be avoided. It can lead to competitive and jealous feelings. I broke my own rule in the example above for one actor because I thought her performance was potentially insightful.

Omit anything that seems likely to cause hurt feelings. Describing 100% of your reasons for casting decisions is not necessary.

Do admit when there were mistakes you made or things you want to improve in the future.

Celebrate the casting as an achievement to which the entire group contributed.

Also, if you know at the beginning of auditions that you’re going to write this recap later, it will cause you to self-assess and learn along the way. It’s sort of like avoiding cognitive dissonance with a future version of yourself. Be the best director you can be now so you’ll like yourself later.

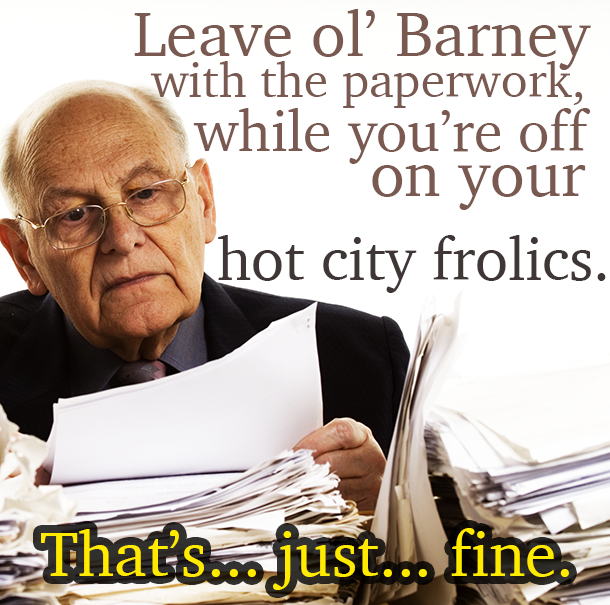

The Follow-Up Actions

Okay, this stuff is boring. A lot of crossing T’s and dotting I’s. But somebody’s gotta do it. To be a happy bureaucrat, you need to track each cast actor’s status and make sure you cover all the steps.

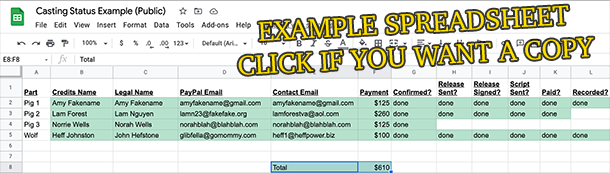

I made an example spreadsheet for tracking casting info. All the information in it is fake. You’re welcome to make a copy of the sheet and reuse the parts that you like.

I’ll briefly go over each checkpoint.

1. Confirmed?

I described the communication earlier in “The Day After” section. You make sure the actor wants the part, and they’ll be able to record everything in a reasonable amount of time. If you don’t get a confirmation response in 48 hours or the actor doesn’t want to record the part under terms that work for you, politely thank the actor and move on to the next choice on your short list.

When they say “yes”, get all the basic information which should include the name they want to be credited by, the legal name you’ll use in a release agreement, and info needed to pay and contact them.

2. Release Sent?

I will give you zero legal advice in this article, because I’m not a lawyer.

You know what I am? A generalist that took one business law class along the way, and figured out how to hack together copy-and-paste contracts. My dubious skills and certainly the contracts I use are not transferrable.

But here is a link to an example release agreement from the wonderful Voice Acting Club.

Without giving legal advice to you, I’ll tell you about some of my choices. And you’ll need to decide for yourself what you’ll do, perhaps with counsel from Rudy Giuliani.

When working with voice actors, it is important to me that the agreement clearly shows the actor is providing recordings as a work-for-hire. I want to own the rights for simplicity’s sake.

I don’t work with actors under the age of 18, for legal reasons. My understanding is that contracts signed by minors would not hold up in court.

I use an electronic signature service to make the contract signing fast and simple. Waiting for physical signatures or print-sign-scan solutions is cumbersome and slows the pace.

The two electronic signature services I’ve personally used and can recommend for their ease-of-use and reliability are DocuSign and RightSignature. I’m sure there’s others that are good too. If you’re sending out more than a few contracts, definitely look into templating features that allow you to upload just one document and reuse it for multiple contracts.

3. Release Signed?

Give the actor time to honestly review and think about the release agreement. They might confer with a lawyer or someone they trust. I like to say, “if you need more than a few days to review, please just let me know.” And in twenty years of working with about a hundred contractors, signing release agreements, NDAs, etc. I’ve never had a single disagreement or problem around contracts. Never push on somebody that wants to take extra time, e.g. a week, to review your contract. Those scrutinizers are very rare, but when you meet them, they tend to be the most reliable people you’ll find.

4. Script Sent?

Send the script and everything an actor needs to record lines for the part.

The obvious reason for doing this is so they can record. The less obvious reason: you are about to pay them, and it gives them one more chance to gracefully back out before you do that. Maybe they see something in the dialogue that is offensive to them. Maybe they’ve made a time management mistake, and there’s no way they can complete your work when you need it.

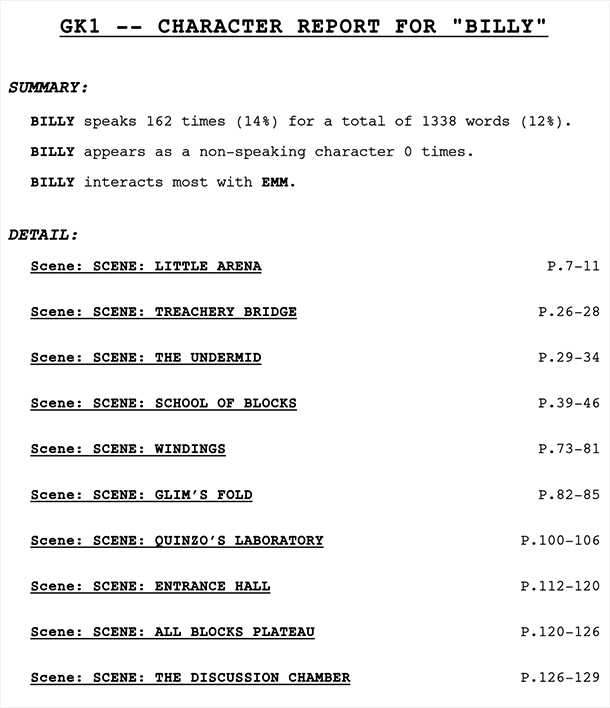

If your script is very large, I recommend sending the actor an edited script that contains just the scenes you need them to record. In this case, definitely leave in the lines of other characters they are speaking against as well as any context that will help them. It’s more work for you to do this, but it reduces the chances of actors missing lines. Alternatively, if you’ve got screenwriting software, you can generate a character report that lists all the scenes a character appears in, and send that along with the full script. Below, you can see one that I sent to Kyle Chrise for his “Billy” part in The The Godkiller - Chapter 1.

5. Paid?

Pay the actor upfront instead of waiting to receive recordings. Pay upfront because:

It saves you time in discussing payment.

It establishes trust.

It (paying fast) becomes a perk to actors.

It keeps the pace fast.

I covered more details of this in Part 1, including specific things to do for reliable payment via PayPal.

6. Recorded?

It’s a great day when you have that WAV file in your hot little hands.

After you get the recording, review it as quickly as you can, ideally within minutes of receiving it. (You’ll see why in a moment.) Bring up the script. Play the recording with headphones on. Verify that every line is present and correctly read.

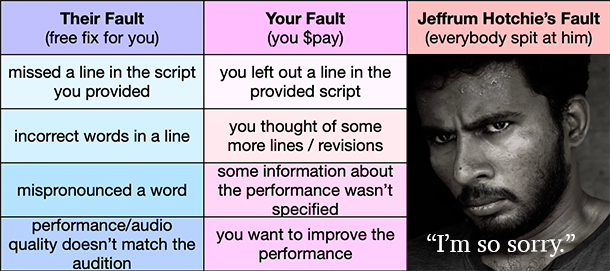

If a line is missing or objectively incorrect, you simply ask the actor to give you a new recording with that line.

If the audio quality is worse than the audition recording, you should ask the actor about that and see what can be done. They almost certainly recorded in their home studio for both audition and final recordings. Maybe they just need to turn off a fan or get closer to the mic.

The rule is basically that the actor will fix anything that is objectively their fault for free. Anything else, you should expect to pay.

How much? Strictly speaking, you’d pay the minimum session fee again. But if there’s just a line or two to fix, and the actor’s got everything set up to easily record, they may decide to give you the line for free or significantly less.

You know the 5-second rule for picking food off the ground? I think it’s kind of like that. Say an actor just barely got done recording your script, like less than an hour ago. They’ve probably still got the character dialogue in their head and their gear set up to record. They might not mind spending 5 more minutes to give you a retake without billing you for a full session. So in that case, maybe just ask them how much they want to record some retakes. But be prepared to pay a session minimum.

This possibility of getting some extra work done without a full session minimum is one reason to review the recordings very quickly. But also, it’s right to clearly indicate the job is done soon after receiving a good set of recordings. Then the actor doesn’t need to worry about you, the Hanging Client of Damocles.

There is a more nuanced and complete description of “revisions, pick-ups, and extra takes” in the Voice Acting Club’s excellent Indie Rate Guide.

Editing

I want to give you a rough idea of what’s needed for editing without describing how to do it all. You can use keywords below to look up tutorials for the specific editing software (or “digital audio workstation” / “DAW”) you’re using.

Edit in a separate copy of the WAV file to preserve the original.

Run a noise removal filter to remove continuous noise from the vocal performances.

Compress and normalize the audio so that it’s easy for you to hear it in your headphones. You may use further compression or a “match loudness” function later.

Delete the extra takes or non-performance audio that you don’t want to use. Voice actors will typically give you 2 or more recordings of each line. Pick the ones you want in your game, and delete the rest.

Remove or reduce loudness of breaths and mouth noise.

Remove plosives (pops around “P”s and other hard consonants).

Remove sibilance (hissing around “S”‘s and other soft consonants).

Chop the recording into clips that match the needed assets in your game. This is often accomplished by setting markers on the edited audio and then performing an export.

Which Audio Editing Software (DAW) to use?

I used to give Audacity as a free, open-source option, but there is some “spyware” controversy around it now–judge for yourself. I hear good things about the free version of Reaper, and it’s very popular. I love Adobe Audition, and have used it for a decade. If you’re already a Creative Suite subscriber, definitely consider it. Pro Tools is the “serious” option that nearly every professional audio engineer uses. But it’s expensive and harder to learn, so I’d only get Pro Tools if you aim to be some super-advanced audio wizard or exchange project files with them.

Cast Perks and Community Spirit

There are some nice things you can do to boost goodwill and rapport with your actors. You might be in a more transactional mindset, and that’s okay. As long as you’re treating everyone fair and professionally, your casting call will be an above-average experience for the actors that choose to spend their valuable time with you.

But if you’d like to be more community-minded, invest in longer relationships, or build up some good karma, here are some ideas:

Describe the actors that were cast for parts as “the cast” of your game. It’s technically true, but a tiny stretch from what a “cast” is in a traditional production from theater, TV, or film. When you say actors are in your cast, it’s a small gesture of membership and inclusion. They are on your team.

Provide a channel, mailing list, or private forum for cast members that allows them to talk to you and other cast members. On Discord, this is simple to do, and if the auditions were held there, then everyone is already on your Discord server.

Create an IMDb page for your game, listing all the actors in your cast, as well as “crew” (programmers, artists, musicians, etc). I did not think to do this until one of the cast members offered to create one. (Here it is! I’m proud of it!)

Give a free copy of your game to all cast members.

Credit actors in your Tweets and other promo. It’s easy to do if you’re already making those “pay attention to my game” posts.

Follow each other on Twitter, LinkedIn, and other socials.

Hang out a bit, talk, learn from each other.

Plug the professional services of cast members when good opportunities arise. (I’m going to plug somebody in the next section. Just watch!)

Feeling Overwhelmed?

At the beginning of this 4-part series, you might have said, “Yeah! Voice acting in my game! Let’s do this!”

But now, after reading tens of pages describing all your little tasks, you’ve got doubts. It can be a massive amount of work. Especially when you do everything the right way.

Well… maybe I’ve been a little intimidating.

I tend to go into concrete detail on how to do things – helpful for some readers, exhausting for others. But there’s plenty of freedom to do things the way that makes sense to you. When something is a prevalent expectation, e.g. don’t end casting calls early, I’ve tried to underscore the message as something you need to do for your reputation’s sake. When something is just my personal best practice, e.g. paying actors upfront, I’ve tried to draw this distinction as well.

Also, you can get help!

It’s outside the scope of this series to describe all your options, but there are talent agencies, casting services, and websites designed to bring you auditions or selected actors for consideration.

If you don’t want to turn over the whole casting process to an outside company, you could run it yourself, but get some help for specific roles:

Project manager – Here is my plug for Erin Lundquist, a certified project manager who can assist with anything from scheduling, to contracts, to setting up IMDb pages.

Casting assistant – Do you not trust yourself to judge all those auditions? You can hire someone to listen through them and create a short list for you.

Audio engineer – All that editing work can be neatly turned over to someone fast on the DAW.

I’m not saying you hire all these people. But for those tasks you truly dread, it may make sense to delegate to contract help.

Who Is Jeffrum Hotchie?

Jeffrum “Jeff” Hotchie is a tragic figure with a cautionary tale.

When he was eight years old, Jeffrum loved doing laundry for his whole family. Every day, he would ask his brothers, sisters, mother, and father, “do you have any dirty laundry I can wash and dry for you?” And on some days, there was no dirty laundry, which made Jeffrum sad. So he went out into his neighborhood and asked other people.

One neighbor said, “you know, people will pay you to do this, right?” At that moment, young Jeffrum knew what he wanted to do with the rest of his life. He ran home, fast he could.

“Mom! Dad! I want to run my own dry cleaning business!”

His father shook his head in disgust. His mother looked at the floor and wept softly.

“No,” said his father, “you must be a game designer.”

And to please his father, Jeffrum did become a game designer. His dreams of neatly packaging customer’s clean clothes in plastic died.

In the coming years, Jeffrum released games at a prolific rate of one every three hours. They were all terrible.

Players hated Jeffrum’s games with a passion. I’m sure that his 12% Refund Policy didn’t help. To this day, Jeffrum is afraid to walk outside his home for fear of being spat at.

What Is Wrong With Me?

Sorry, I just can’t help myself with the weird humor. But maybe there is a point to it.

When you look at the ridiculous, mournful face of Jeffrum, isn’t there something in you that wants to hear him speak? Is his voice deep or high-pitched? Does he talk slow or fast? What accent does he have?

More importantly, when you look at the characters in your game, do you want to hear them speak?

Hopefully, this series has given you a good idea of what it takes to make that happen.

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like