Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

This article takes a close look at the potential time costs lurking behind deciding to go in-house with producing a game promo video.

Let’s say you already have a game and a team that’s working on developing it, and now you need a trailer for your game and are still deciding whether to make it in-house or outsource the production. And now let’s assume you go with the first option of having your in-house team create its own video, and take a look at what’s involved.

There are endless types of game-related videos. You may encounter everything from spliced video capture footage, 2D and 3D motion graphics, to fully animated videos. Of course, different levels of difficulty translate into different time costs, and so game trailers can be seriously all over the map in terms of cost. That all sounds logical, but probably still too abstract, right?

To dig down into the details, let’s consider a hypothetical scenario. With our model scenario, we’ll look at which development team members could help with production, and what each of their roles would be, and ultimately how much time — at least in rough terms — each one might need for his or her part in the production.

We start by making three assumptions for our case scenario: about what kind of video you need, what team members you have, and how you’ll organize the video production process.

The Video : Let’s say you need a trailer, no more than a minute long, to be posted on the game’s website and on Google Play. Let’s assume your video is going to be in English with a native-speaking voice actor, and have music and sound effects.

Your Team : We’ll assume that you have people on board with enough knowledge, skill and experience to handle writing a script, creating graphics for the video, animating them, and syncing it all up with a soundtrack. We’ll also assume that your team is all on the same page, communicates well, and each team member can devote half a working day to the task without interfering with their other responsibilities and assignments.

The Process : you may decide to follow the process we use for creating videos at Alconost: write a script, make the storyboard, record voice-overs, select a background track, string together the animation, arrange the music, and add sound effects. You still may need to fine-tune the process, but how exactly will depend on your particular game and particular team. Since we’re using a hypothetical scenario, video and team here, the process should at least be specific and universally applicable.

At the beginning, your team will brainstorm on things like your target audience, the specific game features that you need to show, the take-away premise of your video, and what kind of “feeling” you want to trigger in your viewers.

Image Credit: StartupStockPhotos, Pixabay

We’ll assign our script to a narrative designer or copywriter — someone who writes dialogues, quest texts or other user-facing messages.

So that the designer/artist, animator and narrator have a good idea of what they need to do, the script will need to answer the following questions:

• What background visuals are you going to use in the video? Are you going to use a simple gradient, 2D detailed art, or a 3D environment? This is something you need to square away at the very beginning to make sure that all visual style and art are consistent. Add references and mark-ups to your script.

• In what order will the game’s top features appear in the video, and how will you show them? If you have a few features that don’t exactly lend themselves to visualization (button clutter, a lot of text, tiny icons) the script needs to state exactly how you will show them.

• What text will you use for the voice-over? Your narrator will read the text you give him/her without editing it to his/her liking, and so the script-writer needs to be sure that the script text is high-impact, error-free and coherent.

Image Credit: StartupStockPhotos, Pixabay

How you choose to show gameplay features can greatly affect, or even entirely determine, the production process. Some possible options:

• Simulate actual gameplay and capture the screen directly from the development environment (this is an option particular suited to games on Unity).

• Make screen captures from the release or test build.

• Put together gameplay footage using graphics sources (required content, e.g., location or inventory items, is modeled from static assets which are then animated).

You may run into a situation where your script is limited by simple technical feasibility. For example, if developers are buried in work and you need to avoid burdening them with capturing gameplay footage from the development environment, your script needs to include only those game events which can be shown using screen captures from the build or motion graphics.

Say for example that our hypothetical video will have 4 scenes with 2D animated game graphics (close-ups of characters, a big array of equippable items, achievements, and a game logo) and 4 screencast scenes which the team has decided to capture from the release build, arrange, edit, and touch up a tad.

Let’s assume the script writer spends 4 hours on the rough script, another 4 hours on editing after running everything by the team and adjusting, and another hour for the final polish. We’ll add another half an hour for selecting references (things like “lively slogan animation” may mean different things to the script-writer and the animator, so it’s better to use more objective directions), and then another half an hour to think how the video’s main characters will be outfitted. Because everyone knows that a garden fairy’s leather armlet doesn’t go with a two-handed orc mace.

Of course, these times can vary widely in either direction. Sometimes you can have a script written in one or two hours, while other times it’ll take several days before you can get everyone to agree and edit accordingly. Not to mention the times where you realize you want to fundamentally rework the script from scratch when you start trying to work out the details. But let’s assume that in our case 10 hours was enough to write a successful script — one that is engaging, logical, and can be realistically worked into a real video.

This is where you create still images and stand-ins that follow the guidance of your script. We’ll assign this task to the artist who, say, usually draws locations and in-game items.

Image Credit: StartupStockPhotos, Pixabay

The first thing is for the artist to unpack the script, read the references, and select art from existing assets (finding graphics sources for characters and of course our garden fairy’s leather armlets in the game graphics archive). Next comes creating the visual style: the artist designs the background, draws the text boxes, and selects a font. Since the script involves sequencing and fitting video captures, the artist needs to figure out how to compensate for the difference in the aspect ratio of the framed screen capture video (which may end up being 1:1 for example) and the trailer aspect ratio (usually 16:9).

When the visual style is approved, the artist will prepare the full storyboard: sequencing scenes from finished elements and drawing in the missing ones. If any video elements are taken from stock images, the artist is going to need to splice in the purchased elements into the storyboard: tweak the brightness or saturation, add shadow, etc.

Let’s assume that in our case the artist spends 4 hours a day on storyboarding and manages to get everything done in a week, including one or two editing cycles. In this case the artist has around 20 hours sunk in the project.

Of course, if our video is only a screencast, the artist will only need to draw boxes for on-screen text and the scene with the game logo, and the time expenditure will be significantly less. But if all or nearly all of the scenes in our video are motion graphics — or if, worse, the graphics have to be drawn from scratch (if you want the video to reveal the back-story for the game world, for example) — time costs for the storyboarding stage will balloon significantly. So, 20 hours for the storyboard for our hypothetical video is really just a theoretical rough value: in any given project it could be less, or a lot, lot more.

The animator will read the storyboard, read the directions and references, and animate the artist’s storyboard. The animator will also sequence the video captures together: the project manager (who we will return to later in the article) has already captured them and given them to the animator along with time codes for successful fragments, and instructions on how to frame and edit them.

Image Credit: sonerbakir, Depositphotos

We align the animation with the recorded voice-over track to synchronize the video footage with the voice actor’s speech and the beat of our selected music — which our project manager has also prepared.

So, we’ll say the graphic animation takes 30 hours, and work stringing the captures together 10 hours. Let’s say the team likes the draft sequence as a whole, but there’s still room for improvement. Now we run the draft animation through three editing cycles (which probably will take 4, 3 and 2 hours: the closer to the final version, the fewer edits needed) and give our animator another hour or so to polish up the final edit. At this rate, the animator will have spent 50 hours.

Time expended on the animation is a strict function of the script. What about the action in scenes with motion graphics a la “the palm leaves rustle” or “the ship approaches the shore, pirates land and the islanders flee”? These actions are different in terms of complexity, and accordingly they will take different amounts of time to animate. The number of animated scenes also matters, of course.

Nor is everything as simple as it might seem with screen captures. If you add in static graphic patches above the video capture or string together one large “reel” of dozens of screen captures to allow the camera to pan across a location and zoom in on different areas — your time expenditure cap will increase significantly.

You can of course record an audio track specifically for your video. But let’s assume that you want to save some time and use an existing melody.

You can use a “native” game track for the video, e.g., ambient music for a location, or a war-like theme, or perhaps stock music. Let’s assume you go with a stock track, one that you picked during the storyboarding stage to allow your animator to align the video footage to the beat and timing of the music.

When the animation is ready, you just need to fit the music to the video length and add sound effects so that a change of scenes or appearance of the game logo is accompanied by the appropriate swoosh or bing. Then we mix in the voice, adjust the volume so that the music and effects don’t drown out the spoken text.

Image Credit: princeoflove, Depositphotos

We’ll assume here that arranging the music, selecting sound effects, and mixing and aligning the voice-over takes around 4 hours, and another hour to make edits and corrections after the team’s input (they didn’t care for the “bing” — because only a “boom” would do, etc.). So we’ve spent a total of 5 hours.

Now we just need to ask the animator to sync the final video with the final audio track — and our video is ready.

The manager does everything to ensure the process moves along in a productive way and that the team is stoked. Otherwise, what’s the point of it all?

In our case, the manager not only captures gameplay footage based on the script, selects the best snippets and picks out the music, but also manages the whole moving machinery of the team. The manager assigns tasks, looks at the interim results, and approves them with the team. If at any point edits are needed, the manager has to articulate the issues and comments in a way that best reflects all team members’ opinions while being cohesive.

Image Credit: ilixe48, Depositphotos

The manager will also need to work with freelancers and contract workers in addition to the team members. In our case we have a native English-speaking voice actor. The manager needs to explain to the voice actor what intonation to use for certain phrases, the timing and pacing of the voicing, and what sort of mood the voice-over should capture. Already having an idea of how to work with voice-over talent will greatly simplify the whole process.

If you are making the video in a foreign language (e.g., your entire development team speaks German, but you need to make the video in English) the task is more challenging. You’ll need to first find a native English speaker to translate and proof your English text (the voice-over script, caption text) and then find a native English speaking voice actor and go through test recordings to make sure he or she speaks without an accent or any kind of impediment.

It is next to impossible to nail down specific time costs for the manager in this kind of scenario, so with the caveat of this being a really rough estimate, let’s say the manager puts in around 30 hours on the project. The actual time spent could be a bit less or significantly higher — it all depends on the individual manager, the team, and the specific demands of the video in question.

The manager is the one who gets shouldered with the majority of the odd jobs, being a part of all stages of the video production. Consequently, it makes sense for the manager to play one more additional role in the project — creating the script. Or vice versa: the scriptwriter could take over the managerial responsibilities. This way the video will have a scriptwriter/director with a holistic vision who is fully responsible for the entire result, and who knows exactly why shots of the items that can be equipped in-game need to showcase a garden fairy armlet, and why nothing else will do.

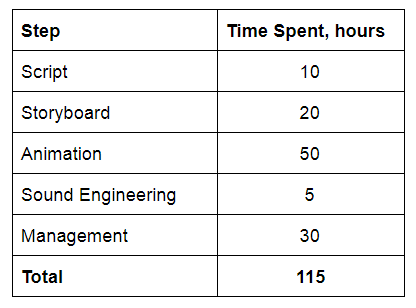

So now let’s put together an estimate of how much time we spent creating our hypothetical game trailer.

An estimate of how much time we spent creating our hypothetical game trailer

It took our hypothetical game development team approximately 115 hours to create our game trailer. And that’s not counting the time spent for the team to have review meetings to discuss the interim results.

Of course, our imaginary team could maybe power through some parts faster, or get bogged down longer, than we have imagined. The team might speed through the script, only to find during storyboarding that they weren’t able to stage and sequence everything quite the way they had wanted. Or, when stringing together the animation, we find that the script omitted a pretty important bit, and now have to back-track. Or maybe the team managed to involve developers in producing the video, capture the perfect gameplay footage from the development environment, and managed in the end to save some time spent on assembling the animation and stitching together the video captures?

Unfortunately, there is no crystal ball to foretell how the process will go nor to give an accurate (and hopefully low-figure) number of hours needed for a given game dev team to produce a given video for a given game.

Actual time spent to create a given game trailer could just as easily be 20 hours as 200. An exact calculation that would do justice to any trailer for any game would shortchange the nuances. And such nuances are legion: from the specifics of a particular game and its screen adaptability to the technical and organizational details of the production and development process, which change from any one given case to another.

In light of the highly unpredictable nature of a new and unfamiliar process for the team which could take an indefinite amount of time, it makes to order a video game trailer from a third-party company, which can give a quote at the script approval stage. In this case, you pay for the product itself — the finished video, and how many hours it will take for the producer’s team to create it is no longer your worry. Meanwhile, your game development team can take on direct responsibilities without having to recast themselves impromptu and put on script-writer caps.

Besides, DIY doesn’t always mean “free.” Your staff has to make the video. And you pay them for their hours, so their time is your money. Try to calculate how much 115 hours of your team’s time costs; perhaps ordering a video from a specialized agency won’t seem quite so expensive after all.

Creating a video on your own is a creative process that will draw on the skills and time of a number of team members and take them away from game development. And since video creation is not a core job for game development staff, it can take an unpredictable amount of time.

The main problem that a game development studio runs into when creating a video on its own is the lack of a streamlined process for working on unaccustomed, uncommon, one-off sub-tasks. Even writing a script can take an unexpectedly long time — simply because you’ve never had to do it before. A promo video script isn’t the same thing as a quest script or game plot.

So, should you order a video from an agency or try to go it solo? Each game development team will have its own take.

Read more about:

BlogsYou May Also Like