Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

'Putting into play' is part of a project that aims to explain, from a cognitive and narrative perspective, the hands-on approach to the design of an engaging and dynamic game system.

"Putting into play" originates from the site Narrative Construction and is part of more than a one-year-long project which goal is to explain from a cognitive and narrative perspective the mind and hands-on approach to the design of an engaging and dynamic game system. With help from cognition-based models, the focus is on the opportunity to explore how our thinking, learning, and emotions work when setting out from scratch towards the desired goal.

To make the most of the post, I recommend reading Part 2 and 3 of the series Putting into play, which provides an orientation.

In the previous part, I recommended to bring along a thought or a feeling that you would like to put into play towards the desired outcome in the creation of an engaging and dynamic game system. However, before we proceed to talk about feelings and thoughts, I will explain what it is that makes the narrative vehicle of meaning-making to propel in relation to the core cognitive activities, which can explain the formula and the setting of a premise.

Since we now have an explicit description of how our mind works (see below) that shows what we are doing when processing information that forms our beliefs, desires and expectations (meanings), which we store in our memory as experiences together with our emotions. Based on the citation below, which I call our core cognitive activities, I will show what it is you are targeting, mind-wise, as a narrative constructor when triggering the narrative vehicle of meaning-making in the creation of a curiosity that encourages perceivers to become engaged/involved.

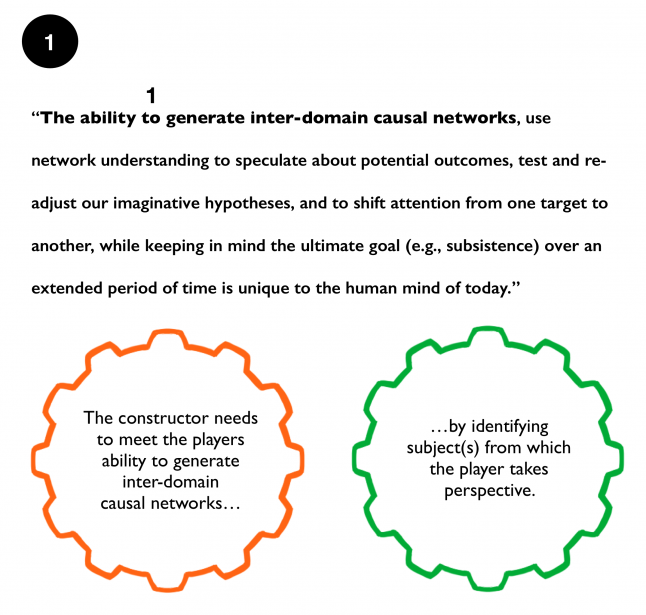

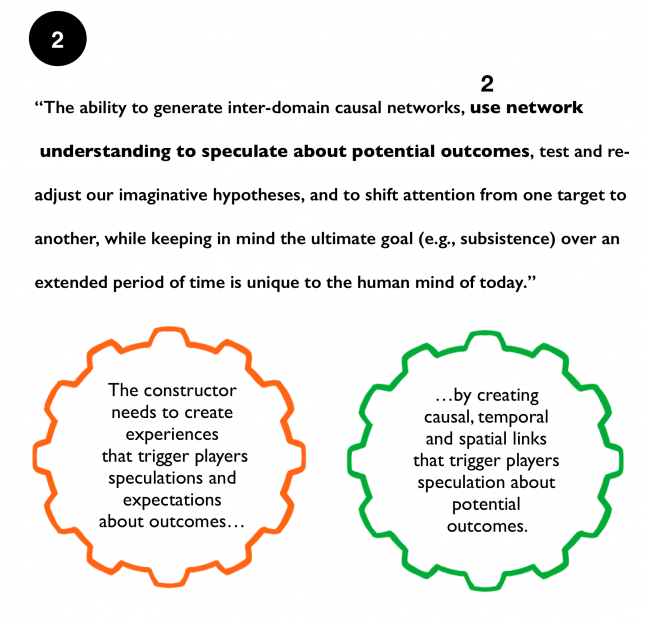

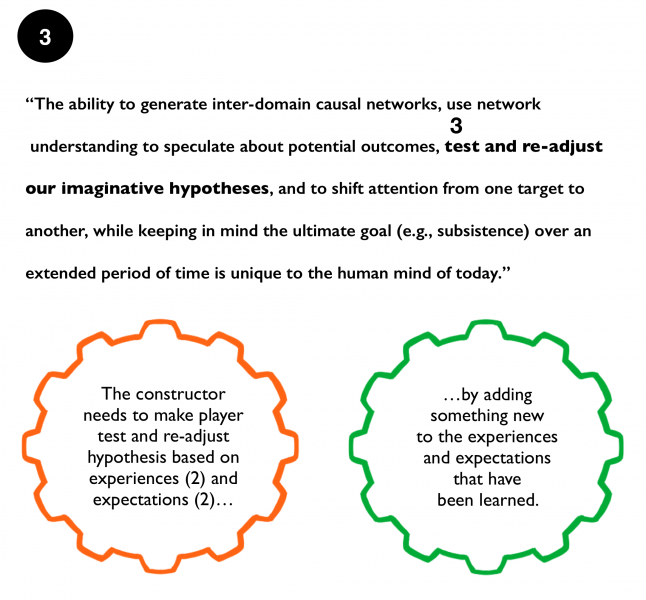

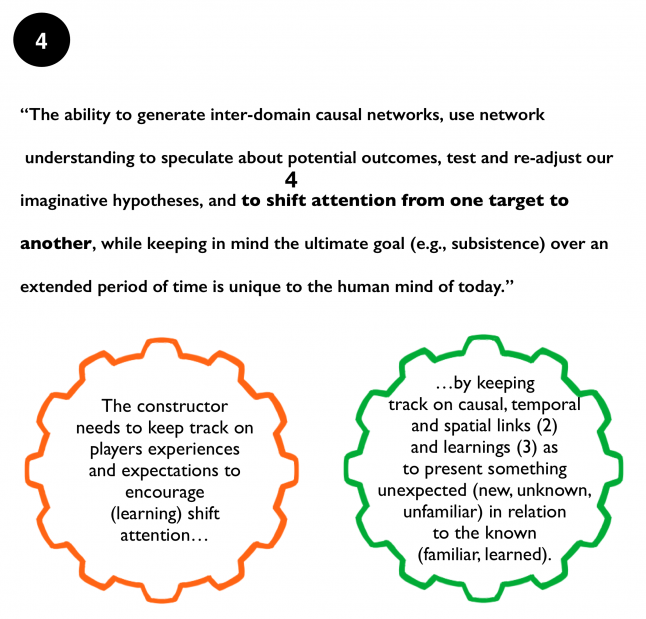

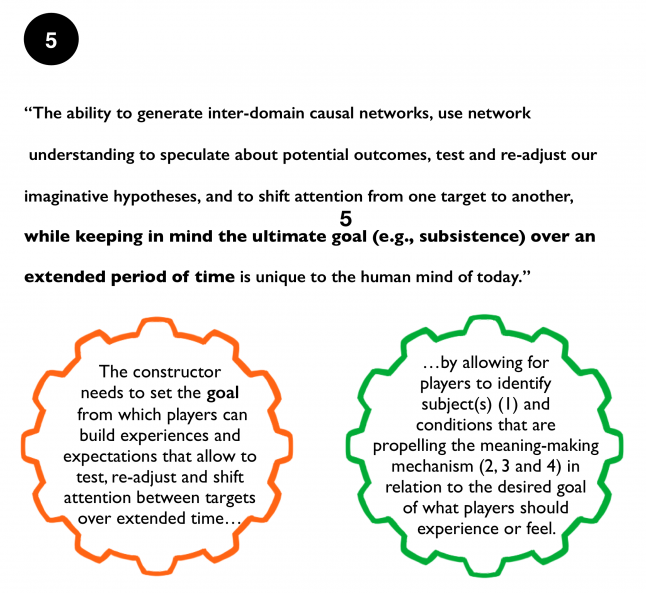

“The ability to generate inter-domain causal networks, use network understanding to speculate about potential outcomes, test and re-adjust our imaginative hypotheses, and to shift attention from one target to another, while keeping in mind the ultimate goal (e.g., subsistence) over an extended period of time is unique to the human mind of today.”

Gärdenfors, Lombard, 2017

Illustration by Linnéa Österberg

Though the description of how our thinking works is a bit tricky to access as the core cognitive activities are performed on an unconscious level. I will repeat the citation in five steps. At each step, I will point to a specific part of our core cognitive activities and add a description of the operations performed from a narrative constructor’s (designer’s) perspective in the creation of an engaging experience that attends to how our learning and emotions work.

While reading the five steps, I think several of you who are working with bringing meaning to a game through sounds, graphics, words, level design, AI, physics, and pacing among other elements, will recognize the descriptions from your daily work.

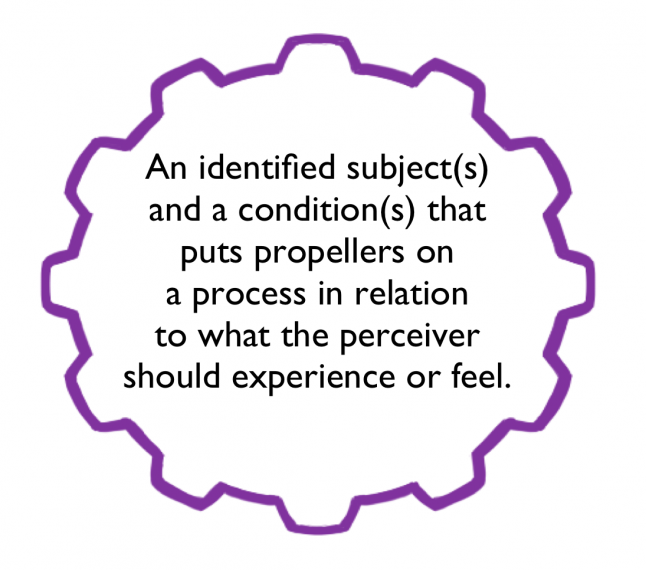

Having mentioned in the series Don´t show, involve the minimum data to set a premise, which triggers the propellor of a process of meaning-making, which meets the perceiver´s beliefs, desires, expectations and feelings. With the help of the five steps (above), we can now get an explicit explanation to which data we need and why we need it as to trigger the narrative vehicle towards the desired outcome in the setting of a premise.

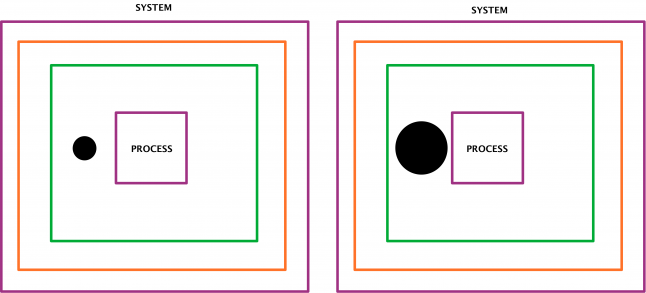

Since I have mentioned different motions through the series in terms of propellors, vehicles, and mechanism, I created cogwheels, which I introduced in the first part of the series, which a friend of mine pointed out can´t spin if they are put together. The cogwheels should rather be seen as a symbol for the cognitive motions that are in progress, mind and machine-wise, in the exchange of inputs and outputs. As interactivity defines the game as a medium it also specifies how to approach the creation of meaning from a narrative perspective. Even if you write a storyline for a game, which craft-wise works as a method during the process to generate, elaborate or get a grip of the logic, causal, spatial and temporal links. You can´t avoid the fact that you will have to specify the minimum of data that defines the core of the game.

As the premise is the main key to keep the direction and orientation on a design process to reach the desired goal. I will show an example of how a minimum of data could look like that opens up for the construction of a core, which triggers the core cognitive activities of meaning-making.

Based on the description above of the premise. Let us say that we identify a subject that is small, from which we take perspective. If the subject should be perceived and conceived as small something needs to be big. When defining something to be small, we have giving meaning to a relation between two contrasting elements, which gives us a condition of two contrasting systems that puts propellors on a process.

To understand what the relation to what the perceiver should experience or feel will add to the rules, behaviors, and goals of systems and objects that the player will interact with. Check the first part of Putting into play and the example which shows how the game designer Fumito Ueda is giving meaning to the player's experience and feelings in the making of The Last Guardian, which core proceeded from an identified subject that was small in relation to something big.

The Last Guardian, by gen Design, Sony Interactive Entertainment

Let us say that we have a premise, which looks like follows:

This is a game where the player will feel the insecurity of being a family guy who doesn't see any other way of earning money than going down a criminal path. At the same time, the fear of being exposed by the family, friends, and colleagues would be an immediate problem.

Compared to the previous example of the minimum data needed to trigger the narrative vehicle by the identification of contrasts (small/big), the abstraction level of the premise above has been lowered. As the subject and the conditions that create a propellor has been given “more” meaning and where the feeling that the player shall experience is defined. As a thinking exercise, you could try by using the premise above or another one to find the core of the game by looking for the minimum data of contrasts that could form the core mechanics from which the game could be built on.

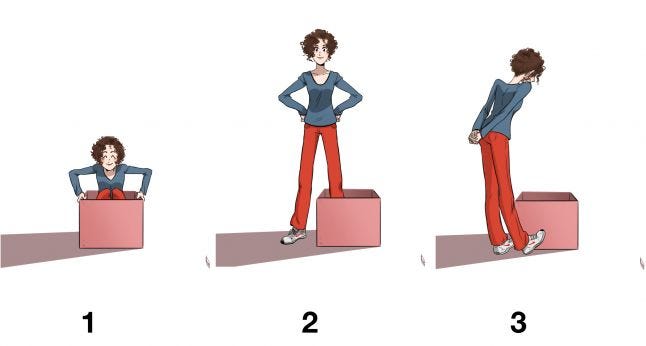

With the five steps in mind and the premise, I will continue in the next part to focus on how to understand thoughts and feelings in the creation of an engaging and dynamic game system. Since your engagement and responses matter to the evolvement of the series. If you have any questions or would like to share your thoughts, don´t hesitate to send me a note (contact added at the end). To make it easier to communicate, you could use the communication model, which I presented in the previous part. By adding a number from one of the pictures below together with the part of the text you refer to, it will be enough for me to get an idea if something needs to be clarified before moving on, and so on.

1. I am with you.

2. I am curious and want to learn more.

3. Now you lost me.

Finally, a special thanks to Linnea Österberg for the fantastic illustrations that make the invisible visible.

Until next time, take care and stay curious!

Katarina

Part 1 Putting into play - A model of causal cognition on game design.

Part 2, Putting into play - On narrative from a cognitive perspective I

Part 3, Putting into play - On narrative from a cognitive perspective II

Don't show, involve (series in three parts)

Narrative bridging on testing an experience (series in three parts)

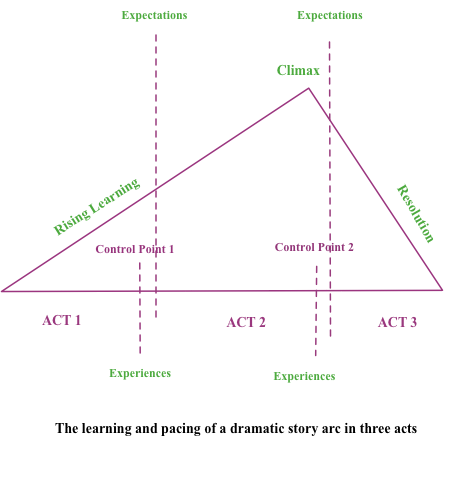

In the third part, you can, for example, find a similar description of the five steps applied on a three-act structure, which describes the control and pacing in the building of experiences in relation to the expectations.

A short guide to the 7 grade model of reasoning

Narrative patterns of thinking (posted before the 7-grade model)

Where I work there are no conflicts (posted before the 7-grade model)

Gärdenfors, P., Lombard, M., (2017). Tracking the evolution of causal cognition in humans. In the Journal of Anthropological Sciences 95. p.219-234

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like