Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

Antithesis is an asynchronous 1v1 horror multiplayer game involving a player on PC and a player in VR. After 15 weeks of development from a studio of 26 Northeasetrn Game Studio students, here are each team's thoughts on the process.

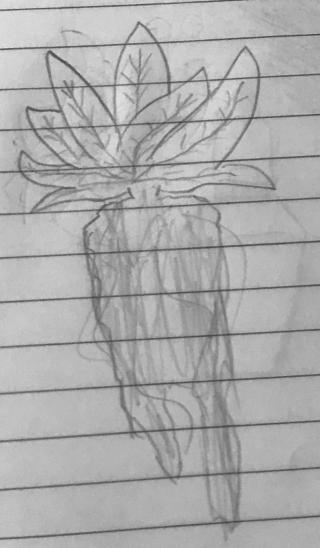

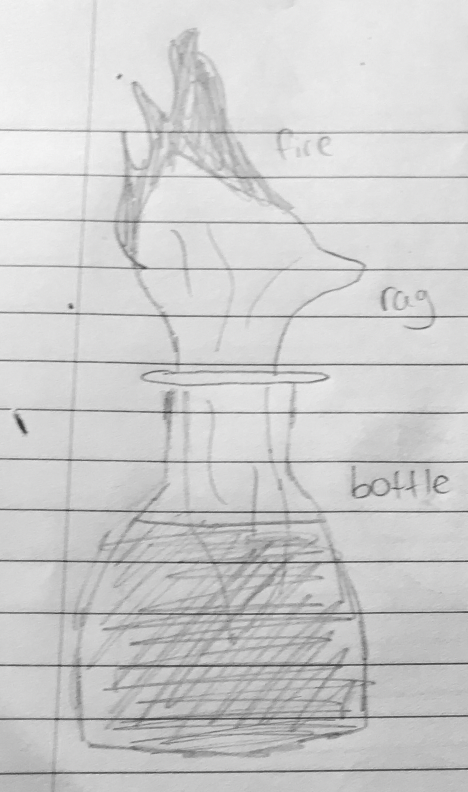

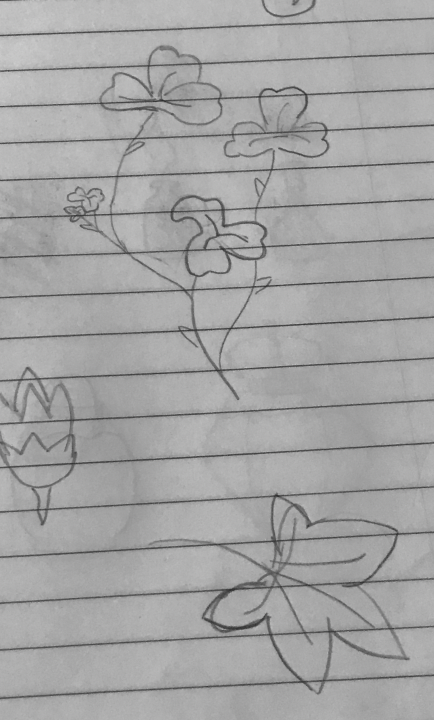

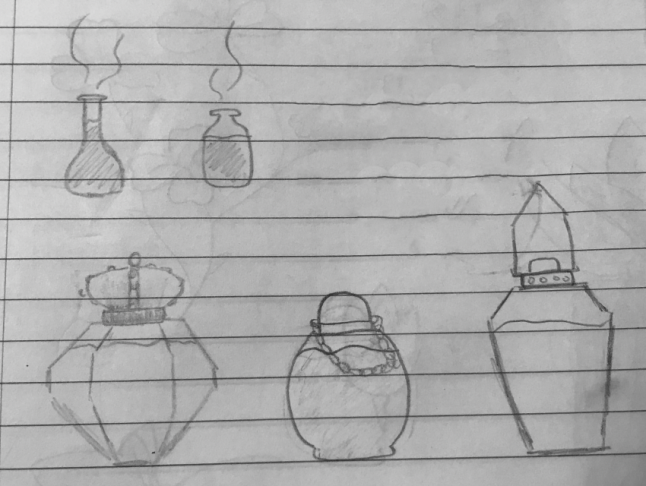

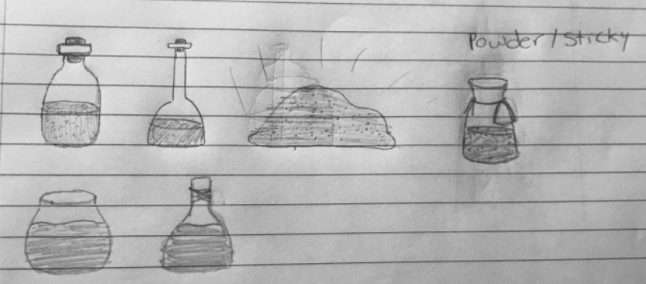

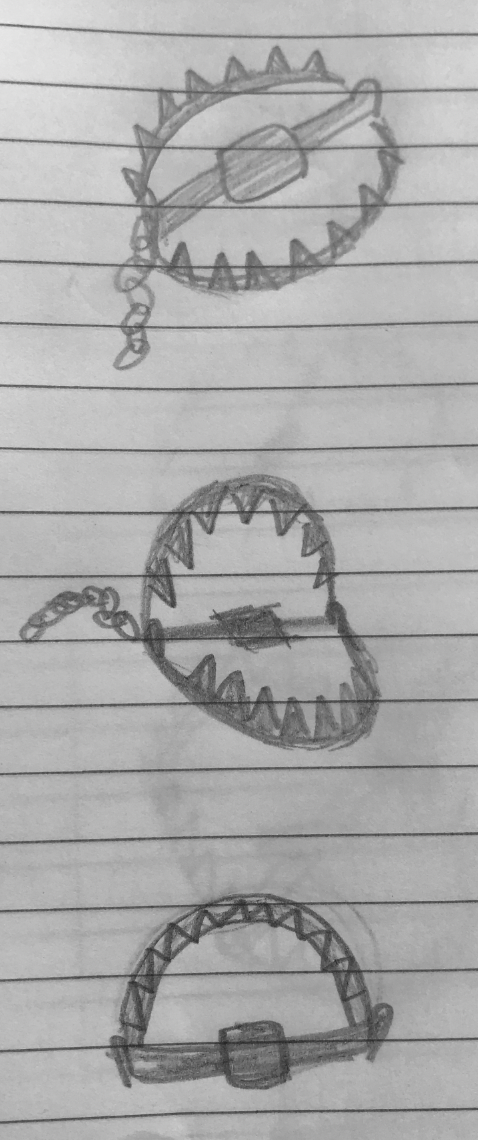

Antithesis is an asynchronous 1v1 horror multiplayer game involving a player on PC and a player in VR. In Brigham Township, a former townsfolk turned caster has placed the entire spell under his control. The caster character is controlled by a PC player, who may lay minions and other traps around the map to prevent the hero from gathering the materials needed to break the spell. The hero, who plays in VR, must make their way around the map in order to collect the supplies necessary to break the spell and free the town while avoiding the minions that the caster has placed. It’s a game of prediction, mindgames, and resource collection.

This game was designed at Northeastern University as a part of its Game Studio class during the Fall of 2020 and was led by Professor Sam Liberty and lead producer Kieran Sheldon. Students were broken up into their respective teams, each with a team lead. These teams included design, art, development, marketing, narrative, production, sound, and UI/UX. These teams collaborated with each other to meet deadlines and coordinate when their tasks overlapped. Teams worked within their own groups to create what was necessary for that discipline of the game. The project was designed in Unity for the Oculus Quest (for the VR player) and PC.

What went right

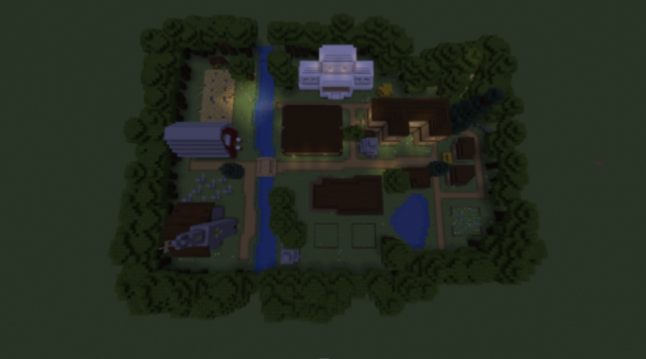

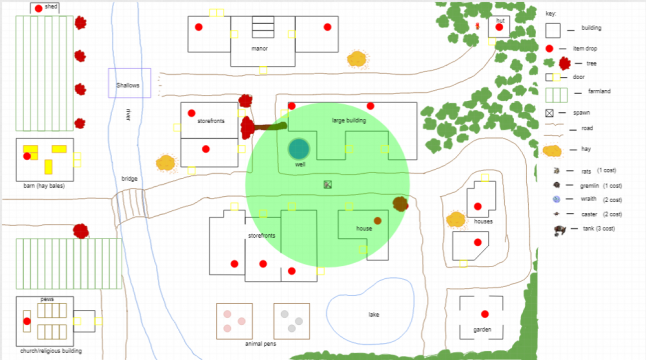

After some initial brainstorming everyone had a clear idea of what we wanted the game to be in the end, that being an Asymmetric 1v1 VR Horror experience. With that as the end goal we started work on a variety of prototypes. The first two prototypes were done through the website Roll20 in order to simulate a paper prototype. The third and final prototype was done in Minecraft in order to more accurately simulate the final product. All the prototypes had different goals and things we wanted to test and accomplish. The first paper prototype was done to iron out the mechanics of both players, determining what monsters would be used, and determining if the gameplay loop of placing down monsters in response to a player’s actions was enjoyable. The second prototype had the goal of finalizing the map and aspects of the game which included the monster list, the map, and the traps a VR player could use. The final prototype was done to get an idea of how the game as we designed would play in real time.

What went wrong

We were guilty of over scoping the project as we initially planned to include seven monsters total, on top of other elements that just weren’t feasible. Additionally, when it came to balancing the prototypes, especially in the first one, we weren’t great at getting it right in terms of the power ratio for both sides. As a result, there were a few iterations of the game where certain monsters were incredibly dominant while others were essentially worthless. Additionally, some iterations of the game didn’t convey any of the feelings we wanted them to but this was amended in future iterations.

Adaptations

Because of the COVID-19 things didn’t play out as we expected. Making a paper prototype was impossible since we could not all meet up in the same place as some of us were remote while others were not, but we were able to adapt as we used Roll20 to simulate a more conventional paper prototype but online. Additionally, we needed to cut down on the number of monsters we had and condense their functions into a new list of monsters.

What went right

We were able to create asymmetrical gameplay between VR and non-VR players. Additionally, player movement and interaction in the VR space worked efficiently and smoothly. When it came to implementing the monsters, they were all implemented in a timely fashion. The Gremlin and Tank were easy to implement and worked effectively with previously written code for enemy AI behavior on top of the tank being a tweaked Gremlin, there was a homing effect that made the implementation of the Caster monster more streamlined, and the floating effect of the Wraith was done with the use of a nav mesh. As a result of decisions made early in development many items, such as potions and traps were easy to implement reducing hassle and creating a much more streamlined programming environment. Another thing that helped was the code being very organized throughout the project, which helped make every script simpler to debug. Communication within the dev team was consistent and frequent thanks to our Discord chat, allowing us to understand the progress that other teammates had made. As far as version control can go, frequent communication and the use of Unity Teams kept the collaboration process fluid and kept us from butting heads too often.

What went wrong

When implementing the monsters, we did run into a few different issues with various aspects of different monsters. The Caster had issues with not updating between shooting and chasing states, as well as not pulling its dexterity from the correct source which made changes to dexterity via traps impossible. The Gremlin stats had to be refined as it was too slow to be effective, on top of needing to be modified so that the player experience was more balanced. The tank's dimensions were not large enough to scale to the model provided by art. We had trouble understanding the function of the Wraith as we originally thought the wraith was the same as the caster, but in actuality was similar to the tank with added “fog” attack. We failed in establishing good connections between different teams led to inconsistencies in ideas of how the game should be created, what the final product would be, and what resources were available to implement into the game. Testing was also hindered by the availability of a VR headset in general. We could’ve used more documentation which might have helped unify the development team more. Sometimes, code was added to places that broke code in other places. Such events could’ve been avoided had the code been set up as was originally documented in the code bible. Additionally, describing how certain systems within the game are programmed would have saved lots of time and work.

Adaptations

Because access to VR headsets was limited, we created a way of playing and testing the game without VR, so that those without access to headsets could work on the game more efficiently. We made various changes to the monsters as they were required after consulting the appropriate parties. The Caster code was rewritten such that the dexterity/speed was returned via enemy script, the Gremlin’s dexterity was increased by 2, the Tank’s collider was modified to be larger to fit with the given art model, and the Wraith was given a unique script for handling instantiations of fog objects at its given location. Finally, a temporary select-and-click system was implemented for monster spawning.

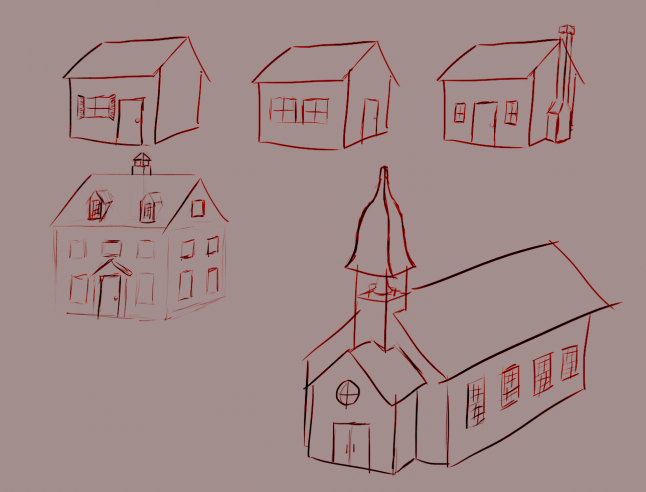

What Went Right

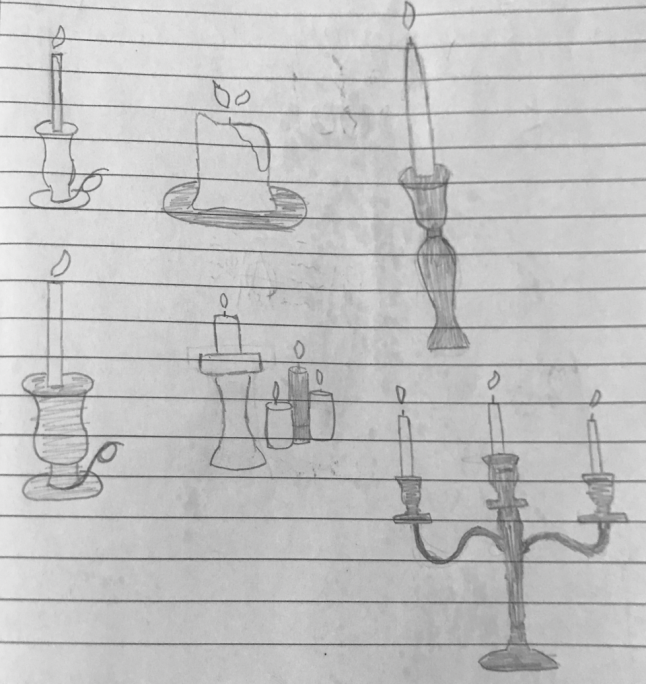

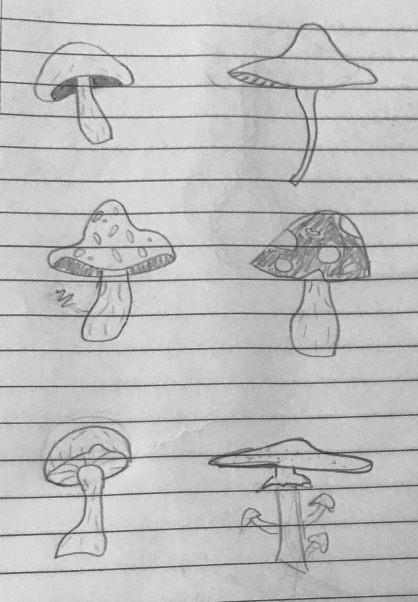

We were able to go through the stages of 3d animation, including starting from a concept and then moving forward into modeling and then animating successfully. Some of the members of the team were more experienced than others in this process, yet everyone contributed well in this regard to some capacity. The feedback process for the concept designs was a smooth process, yielding improved iterations of designs and models the more we presented to the group. These fit the mold of the concept of the game well at the end of the day. Other teams were very communicative and collaborative when it came time to import these assets, resulting in a smooth process from the beginning of the cycle to their implementation in the game. The team stuck to the mood board and atmosphere of the game’s design well, especially when it came to monster designs.

.png/?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

.png/?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

What Went Wrong

Communication wasn’t all there toward the beginning of the game’s development when it came time to work with other teams, leading to overscoping within the discipline. This cut down the amount of assets that could be made by the team in comparison to the amount that were imported free assets. This overscope also caused delays on a couple of models. This miscommunication also resulted in some wasted work during the first couple weeks of production, as some assets were made that design didn’t want or wasn’t going to use in the game.

Adaptations

We had to learn 3d modeling and animation fundamentals through Blender, with almost no one on the team having prior experience with this. As stated earlier, a few designs and ideas had to be scrapped in order to meet deadlines. This led to the idea of implementing pre-designed, free assets accessible on the internet.

What Went Right

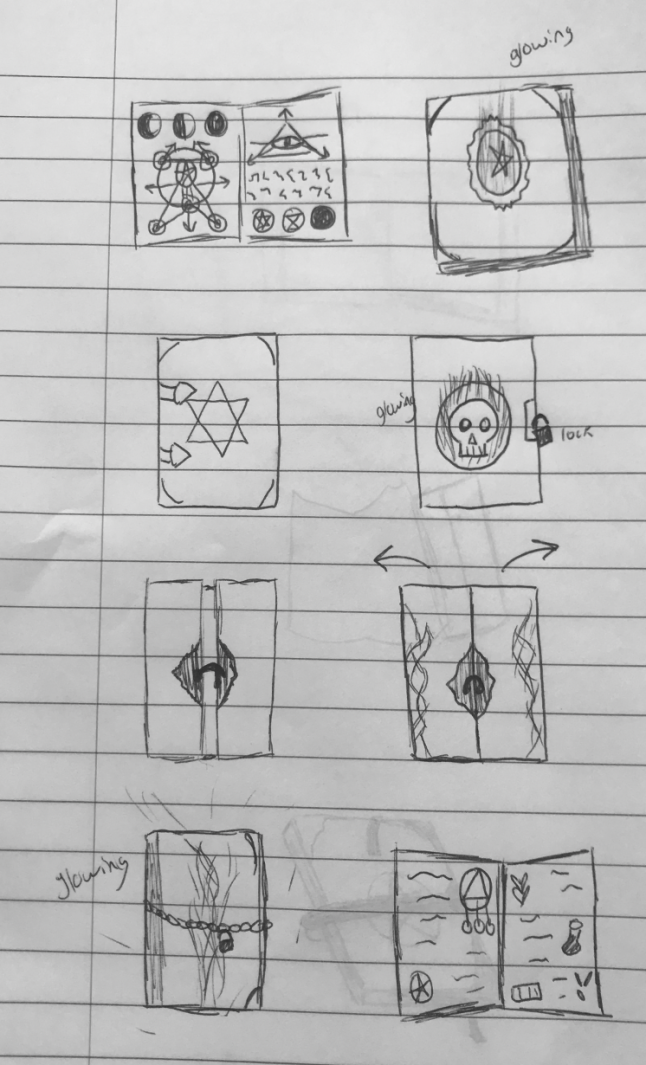

We were able to create a general overview of the way the lore of the game works early in the semester. This was made in collaboration with design in order to shape the way the game functions, balancing narrative and design so that they coexist with each other effectively. We were also able to keep a document with this information in it for easy access, which we updated as things changed within the world. Narrative worked well with other teams to provide narrative-based explanations for world happenings, including plot, monsters, and the world. Towards the end of the project, we were able to create a system, called The Secret Pages, a collectible item in-game that can be accessed in the menu with information on the game’s lore, to effectively give the game’s backstory to the player without overwhelming them in a way that entices the player to learn more.

What Went Wrong

A lot of the work we did felt like it was busy work, as the game was not very narrative based in the first place. The creation of a backstory in the first place felt unnecessary since the game is a 1v1, non-story based competitive game. We had some issues communicating with other teams about the world bible we had created, as we and other teams were sometimes on different pages about what was going on in the world due to different documents used by different teams internally. The world bible was never fully converted into paragraph form as well, which was a failure on our part.

Adaptations

We had to figure out how to create an effective world bible in a short time, as none of us had done one before. We needed to change the story up a bit after speaking with someone of Wiccan religion in order to keep the game as socially sound as possible, as to not misrepresent any group of people. In addition, due to the creation of it, we had to figure out a way for this information to be conveyed to the player, which became the Secret Pages. Later in the semester, we were tasked with assisting the art team with finding assets to implement.

What Went Right

We managed to keep collaborators to a manageable workload despite everyone else’s other class obligations. Trello was used well by all teams and we did a good job getting all teams to use it and update it as they go along. Weekly check-ins (via standup or otherwise) helped to give us time to fix issues and eliminated the need for constant connection. These check-ins also allowed us to fix any issues with workload. Overall, the agile framework benefitted us overall.

What Went Wrong

Maintaining a work-life balance among teams was difficult given a pandemic as well as each student having a full course load. Without a set “working time” (like nine-to-five), this work life balance became difficult to manage when assigning work.

Adaptations

Nobody really had production experience going in, so a lot of what we did was learning on the spot. Navigating this new role while also dealing with a pandemic was a challenge. We had to adjust the workload for teams on several occasions depending on over-assignments or other issues. We needed to be as flexible as possible due to this game being produced inside of a class instead of a standard workday.

What Went Right

Given that none of the team had any previous knowledge or experience with sound production, all of the team members learned a considerable amount of information and understanding regarding sound implementation in games. Our final audio files that we acquired from the Unity sound packages fit well with the theme of the game. Also, the team was very cohesive in general.

What Went Wrong

With everything being remote, it was difficult to share our progress with the other teams. It is difficult to share your computer’s audio over Zoom, so we had to rely on the design and narrative teams checking the audio files on their own.

Adaptations

As stated before, none of the team had prior experience with sound production, so everyone had to learn new software, concepts, and approaches to properly find and implement sound files. This included creating mood boards through mediums such as Pinterest, research into spatial audio, utilization of sound to signal threats, and extensive experimentation in Unity sound packages.

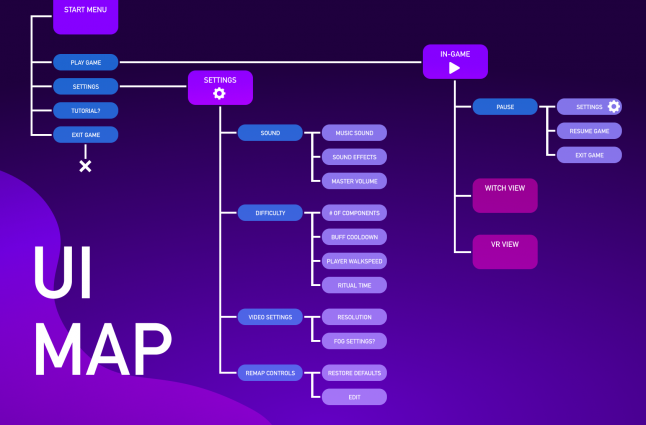

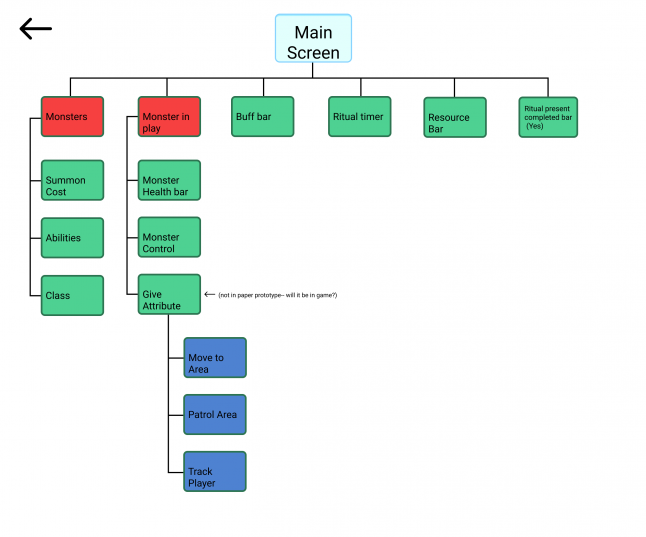

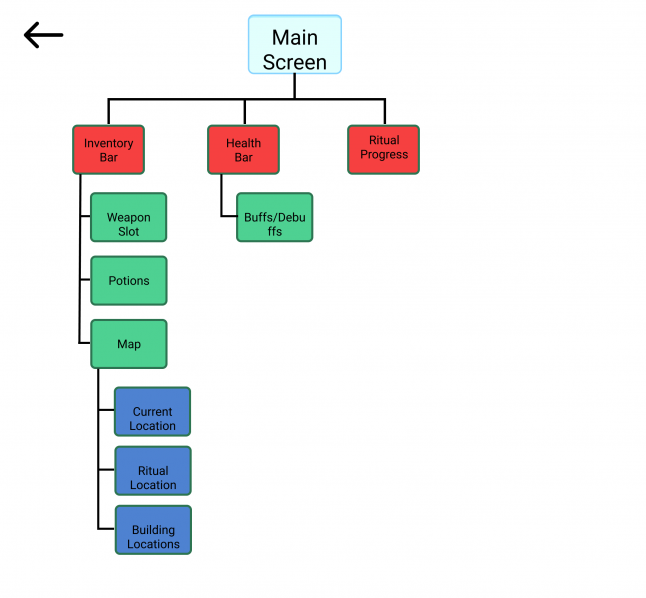

What Went Right

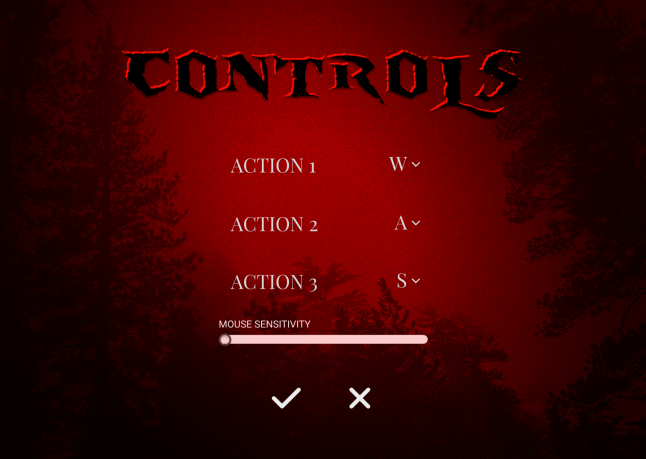

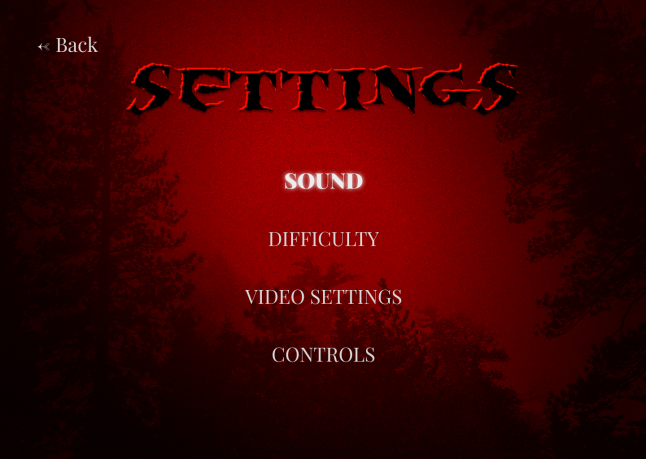

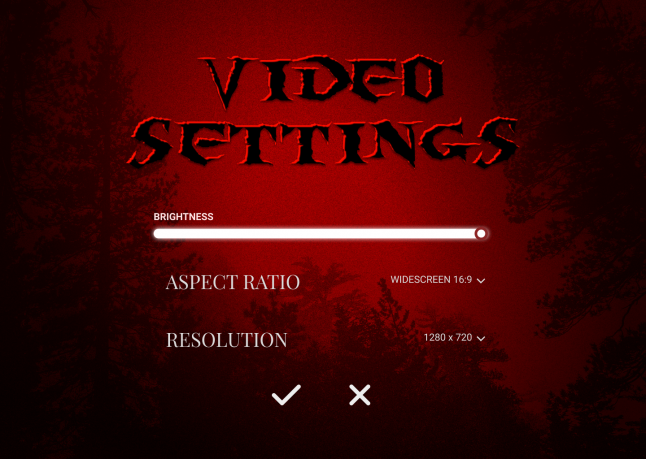

In general, the UI/UX team proved to be a very cohesive team with a high amount of teamwork and positivity present throughout the entire timespan of the project. From the very beginning, we had a clear plan on what goals we had for each coming week, and the vast majority of those plans translated to real progress. In our execution of this, we effectively utilized golden paths to clarify what the team had to do and the workload that would be delegated to each specific team member. Additionally, the conduction of the user testing went smoothly and proved to be a very helpful source of constructive feedback.

What Went Wrong

Some of the UI/UX applications to the menus and the screen for the player acting as the caster was difficult to implement as a result of lack of clear vision. Also, as a result of team members being quite new to UI/UX in general, the team leader was responsible for answering questions and explaining concepts very often, and the work for each week took longer as a result.

Adaptability

In order to construct the UI/UX necessary for the game, the team leader had to introduce Figma software to the rest of the team. This software allows for the creation of wireframes and other essential components for the game. The creation of a detailed plan/schedule also helped plan out weeks where team members would be required to dedicate significant amounts of time to learning software or where team members would be very busy with other work. This facilitated incorporating lots of iteration throughout the project timeline.

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like