Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Gamasutra's design columnist and noted consultant Ernest Adams returns with his perennial reader-favorite column, devoted entirely to exploring the design foibles of games, so designers of the future can avoid making the mistakes of the past.

It's the end of the year, and that means it's time for another roundup of game design errors sent in by loyal, yet outraged, readers. This year I have eight, which isn't very many, but I look at them in a little more detail than I did in earlier columns.

When a game offers help or advice, players normally trust it because they assume that the game knows better than they do how to win. Consequently, few things are more confusing than help that isn't helpful -- help that comes at the wrong time, or is irrelevant in the current circumstances.

Ben Ashley writes, "Tips need to be pertinent! Battlefield 2: Special Forces suffers from this. The grappling hook is an item of equipment that is only carried by the assault class.

"So, when playing another class, why on earth does the game come and helpfully tell me I can use my hook to get on the ledge above me? I don't have a hook. This causes quite a bit of confusion for the new player."

AI-generated advice is tricky to tune well, and advisor characters in complex economic simulations often get things wrong. But when a game advises you to do something that is currently impossible to do, that's more than a tuning problem, it's a Twinkie Denial Condition. Bad game designer! No Twinkie!

Many games include both rewards and punishments. In Space Invaders, you get points for shooting aliens, and you lose lives when they shoot you. Simple. The trick is balancing them appropriately. As a general principle, you should always reward more than you punish.

When it comes to time limits, it's good to reward speed, but not good to punish slowness. The jockey who comes in first wins the prize money, but the one who comes in last doesn't have to pay a penalty. And nowhere is this principle more appropriate than in puzzle games. People have differing amounts of brain power, and puzzle-solving requires time and patience. Someone calling himself "Aguydude" wrote in to say,

"When I call a game a 'pure' puzzle game, I mean that the game does not require any sort of reflexes or timing. I'll occasionally play a pure puzzle game with a time limit, which is bad. Equally bad are puzzle games that use lives or something similar to limit the number of attempts the player can make at solving the puzzle. Forcing a player to redo all of the previous puzzles because they made errors in the current one only serves to discourage them from playing, if they want to avoid meaningless repetition."

A puzzle game with lives? A puzzle game that punishes you by making you repeat solved puzzles? That is serious wrongthink. If you want to reward the player for solving a puzzle quickly, be my guest. But don't punish him for taking his time. As we say in the world of game accessibility, "there's no such thing as too slow."

In Bad Game Designer VII, I condemned extreme rule changes when fighting boss characters. The opposite is just as bad: bosses that are nothing but more powerful versions of enemies the player has already seen. My friend Gabrielle Kent recently started a Facebook discussion about boss battles, and several people chimed in with their own pet gripes.

Gabby said that to her, the things that make a boss battle boring are, "stupid amounts of repetition, ridiculously high/replenishing energy [i.e. boss health] combined with unimaginative gameplay (yawn), and powered up versions of previous bosses."

Gabby said that to her, the things that make a boss battle boring are, "stupid amounts of repetition, ridiculously high/replenishing energy [i.e. boss health] combined with unimaginative gameplay (yawn), and powered up versions of previous bosses."

She also hates boss rushes -- having to defeat the same batch of bosses that you've already defeated once before. I agree. This shows a lack of imagination (or time) on the part of the game designer.

Sarah Ford added, "One of the worst I've sat through is at the end of Final Fantasy X. Spend the whole game chasing this epic whale thing and the last boss is a bin lid with legs. Total anticlimax. What's worse, you can't even die. What's the point in that? It's not even a short symbolic battle, it stretches out forever and the thing keeps healing itself. Rubbish."

Harryizman Bin Harun also wrote to me from Malaysia to complain about endlessly self-healing bosses. I think it's fair to say that gamers hate them on a global scale.

Someone named Jessica mentioned bosses that are utterly invulnerable to all but exactly the right attack, as in the Lord of the Rings action games: "Sure, a seven foot tall Uruk-Hai is going to be tough, but after fighting eighty of his minions, I would think that whacking him in the head with a sword would do something similar to what it did to them, even if I wasn't whacking him in the head at the time when he was most vulnerable.

"I would have been satisfied if the special moments did more damage, and the conventional attacks did less, but the way it was left me totally unsatisfied, and uninspired to continue and finish the game."

Jessica also pointed out that in Call of Cthulhu: Dark Corners of the Earth, at one point all it takes to defeat a certain boss is to press a button -- but you must wait until the boss attacks you, and not press it early. This is a severe conceptual non sequitur. The button and the boss attack are not related, so to avoid getting whacked, it makes sense to push it as soon as you can. She was doing the right thing in a sensible way, and the game punished her for it.

So, a few rules for boss battles:

Bosses must be different from other enemies.

Bosses must not be so different that nothing the player has already learned is of any use.

Bosses should not be invincible to all but exactly one thing (that makes it a puzzle, not a battle).

Fighting bosses should include variety, not endless repetition.

Bosses should not heal themselves (or not very much, anyway).

The key to a boss's vulnerability should not be a conceptual non sequitur; it has to make sense.

Dead bosses should stay dead. (See Bad Game Designer V.) If they come back, they should be interestingly different each time (think of Dr. Robotnik in Sonic the Hedgehog).

I'm sure you can probably think of some more.

Good boss battles cited in Gabby's discussion thread included GlaDOS from Portal, the Colosssus in God of War 2, various bosses in Yoshi's Island, Scarecrow in Arkham Asylum, Malocchio in Interstate '76, and Shadow of the Colossus, which was a game consisting entirely of bosses! All worthy of study.

If you've been reading the Designer's Notebook for a while, you'll know that I'm not a fan of save points; I prefer on-demand saving just in case Dad (or Mom) says "Switch that game off right this minute." But some players really enjoy the tension of not knowing whether they're going to make it to the next save point, so I have to acknowledge that save points are here to stay. However, they do create problems if implemented badly.

I mentioned this Twinkie Denial Condition briefly all the way back in Bad Game Designer V, when I introduced another one, the uninterruptible movie. If you put a save point right before a movie, every time the player dies, he'll have to see the movie again. If you can skip the movie, it's not that big a deal, but some games put their save points right before other kinds of long, non-interactive sections of the game, and the player has to go through it all every time he reloads.

Kaftan Barlast describes one in Mass Effect: "Right before the boss fight on Artemis Tau you have to go through a conversation and an unskippable elevator ride every single time you die. And this is with a game that has an actual save system, but they disable the ability to save the game before and during the fight."

Steven McDonald also mentioned Deadly Creatures on the Wii, in which you have to walk for a minute with nothing to do following a save point. Generally speaking, there shouldn't be any long walks with nothing to do in a game anyway; but walking through the same territory doing nothing fifteen times is particularly dull.

Bottom line: put your save points after any non-interactive content (cut scenes, dialog, long walks), and shortly before any big fights. If the player respawns with very little health, be sure to put some healing potions (or equivalent) around too, because respawning with low health straight into an unavoidable fight is another common complaint.

I've already addressed the question of uninterruptible movies and games that lack a pause button -- both are Twinkie Denial Conditions. The combination is even worse, as Bas Wells wrote to point out. Suppose you've fought your way through hordes of undead kangaroos, haven't reached a save checkpoint, and a critically important cut-scene begins... when your doorbell rings. You can't pause and you can't see the movie again without starting the level over.

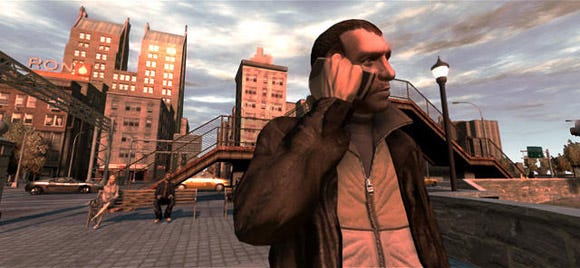

Bas wrote, "To add insult to injury, some games will save after the cut-scene, and it will be gone, a slice of the story missed and gone forever unless you restart the entire level. I remember this happening in Grand Theft Auto IV, then dying on purpose, restarting from the safe house and driving all across town a second time just to be able to watch the scene a second time. I think I must have done this a dozen times in total in just GTA4, and many other games similarly."

I don't think cut-scenes need a full set of DVD controls, but I do think they need:

a way to interrupt them and skip to the end;

a way to pause them;

a way to see them again, once you've seen them once.

The Longest Journey and many other games provide a shell screen where you can revisit the movies that you have already seen once, both for enjoyment and in case you missed any vital clues the first time around. This should be a mandatory feature.

Some storytelling games don't weave their stories neatly in with their gameplay. It can be done, despite what the naysayers may claim, but we often see games in which it isn't. Ideally, the game world and the story world are one and the same, identical in setting and internal laws. When the game world mechanic suddenly changes for the sake of a plot feature, it frustrates the player and destroys immersion.

Sean Hagans and Joshua Able pointed this one out to me, and it's a particularly famous example. Joshua wrote:

"Phoenix Down [a character-resurrection device] didn't work on Aeris in Final Fantasy VII after Aeris died for plot reasons. If it doesn't work, why is that? No explanation? Why does this one time that she dies (even though she died like 100 times before) have to be permanent?

"Either a resurrection vial should work on a story-dead character unless there is an explanation for it, or the character shouldn't die, or you shouldn't have resurrection vials."

The behavior of Phoenix Down (the down feathers of a phoenix bird) seems to vary somewhat from one edition of Final Fantasy to the next, but within a single game it shouldn't suddenly stop working, without explanation, for plot reasons.

All they had to do was give us a reason. "Aeris was too badly injured to save," would have done it. Or "Sephiroth's sword was poisoned." That way, the pure pathos of this highly-charged moment wouldn't have been adulterated with frustration.

The input devices on a video game machine (of any sort) are the most important part of the hardware. Gamers can tolerate low-resolution graphics and tinny 8-bit sound, but badly implemented controls ruin the game for keeps. If you port a game from one machine to another, I suggest rewriting the input device code from scratch, because there are an awful lot of poorly-implemented conversions out there. Sam Hardy wrote to point out two particularly egregious examples:

BioWare's Mass Effect 2 suffers from half-implemented menus. I am able to use my keys to move and select a menu item, but there is no way to press a button and confirm it. I have to mouse over and click. Also, there's no mouse wheel support for scrolling text. The other offense it commits is giving poor information regarding what buttons to press. If I rebind a key, it isn't changed in the prompts that pop up.

Another offender in a similar manner was 2008's Prince of Persia, in which the joystick and button scheme had been imported so well that in order for me to select START GAME I had to mouse over the option then press [ENTER] for it to accept. It wouldn't take a mouse click.

Another common console porting issue is the slower speed at which a mouse and keyboard operate in comparison to a console. Prince of Persia earns its ire from the fact that doing a combo with the left mouse button isn't very comfortable. It's worse when you have to use an uncommon mouse button, such as middle mouse click. Your hand and the mouse isn't designed very well for this and it becomes a source of discomfort.

A controller is not a keyboard and mouse. I realize that portability is a virtue, but when it comes to control devices, it's better to write code optimized for the hardware than it is to create something awkward but supposedly portable. Don't kludge the code; rewrite it. Your players will appreciate it.

I'll end on a simple and obvious one. Scott Jenkins wrote to say, "My No Twinkie pet peeve is games that do not allow background music to be turned off. This seems to be more common in Japanese made games than western made games. The most recent example I can think of is the Legend of Zelda: Twilight Princess for the Wii."

For accessibility reasons, all games should have two volume controls, one for the music and one for the sound effects. Players with hearing impairments need to be able to turn down/off the music; and they're not the only ones. The best music in the world gets monotonous if repeated endlessly.

That's it for this year; there's plenty to think about here, especially when it comes to boss battles and story/game interaction. If you know of another Twinkie Denial Condition that I haven't yet covered (check the No Twinkie Database to see), by all means send me some e-mail and tell me about it.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like