Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

In his latest column, Ernest Adams discusses the creeping return of the adventure game, discussing 'what got better' and 'what didn't get better' in the genre after its famine years.

[In his latest column, Ernest Adams discusses the creeping return of the adventure game, discussing 'what got better' and 'what didn't get better' in the genre after its famine years.]

Life has been a bit weird recently. The other day I decided I wanted to be an opera singer, but along the way I got trapped in a vampire's castle. A couple of hours later, I turned into a ditzy 17-year-old girl, and somehow went back in time to era of the Caribbean pirates, and OMG I can't find my makeup case!

Then I became a cop named Phoenix Wallis, investigating a murder in a deeply ambiguous utopia, and now I'm a tiny tyrant who's trying to get his kingdom back from a usurper.

In case you haven't guessed, I'm playing four adventure games at once. It's fun, if a little disorienting. And that's just in one day. Earlier in the week I tried to become prom queen at my high school, and also to help a famous archaeologist figure out the secrets of a magic amulet.

Game journalists often glibly announce that adventure games are on the point of extinction, but they're wrong. Adventure games will never again be the dominant genre they once were, but they have a well-established market niche and the overall number of people who play them is rising, thanks to the recent arrival of large numbers of female and casual players.

Almost ten years ago, I wrote a Designer's Notebook column called It's Time to Bring Back Adventure Games. Because nearly a decade has passed since that original article, I decided to look at a few of them to see what has happened to adventure games in the interim.

I'm not talking about action-adventures -- action games with a large storytelling element -- but pure adventures, whether they're point-and-click or direct-control games. Here's what I found:

Animation. This is the most conspicuous advance. Most other genres offer their players a limited number of activities -- a shooter is about shooting and a pet simulation is about looking after a pet. But in an adventure game you might do all kinds of things -- load a cannon, oil a door, dance a jig. This means the avatar needs a great many animations.

Most of today's games are still in 2D, but their characters are often displayed with pre-rendered anims built from 3D models. It's easier to build and render a wide variety of animations from a well-rigged model than it is to draw them all by hand.

The movements are smoother and more natural. They're not up to Pixar quality yet, because adventure games don't have Pixar budgets. But they're much better than they used to be.

The roles the player can play. Adventures have always offered the largest variety of roles for the player to play, again because the games are not tied down to a particular set of actions.

As you can tell from the ones I'm playing, there are a lot of options -- probably even more than when adventure games were at their peak. Comedy naturally offers a wide range of possibilities for player roles, and a good many adventure games are comedies.

Strategy First/Momentum DMT's Culpa Innata

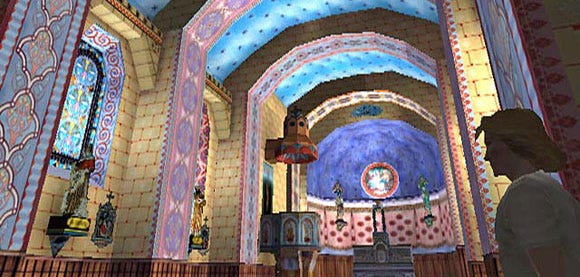

Environments. As with all other genres, the environments in adventure games have gotten a lot better over the last ten years. This is particularly important, because in this genre players like to enjoy the scenery.

Despite the huge impact of 3D accelerators on the rest of the gaming world, many adventure games still use the traditional painted backdrop for each scene.

3D environments are a mixed blessing for adventure games. They're wonderful if the art team can build an environment as rich as a painted backdrop. But with the limited budgets now available, the developers often don't have the resources to model everything, and the result is a game in which the player is constantly running through vast, empty spaces.

Why, for example, do Phoenix Wallis' police headquarters in Culpa Innata look like a gigantic cathedral with about six offices in it? It takes a measurable amount of time just to walk from Phoenix's office to the front door. Still, I'd love to see an adventure game made with Crytek's engine and level of detail.

Harmony. Longtime readers of this column will know that there's nothing I hate more than being jolted out of my fantasy by a cheap in-joke or an anachronism. From what I've seen, the games hang together better as a coherent whole than they used to.

The better artwork helps with that, but I also think that they're taking themselves a bit more seriously -- even the comedies -- and the result is a more immersive and aesthetically pleasing experience.

Audio. No surprise here. As game audio quality has improved generally, it has improved in adventure games as well. This doesn't necessarily mean that the content of the audio has improved, as we'll see.

Unfortunately, adventure games haven't improved in every respect. Here are a few things we still need to work on.

Obscure and insanely-complicated puzzles. The puzzles in today's adventure games seem about the same as in the old days, both for good and for ill, and that means there are still a few insanely-complicated puzzles.

If there's such a thing as a "hardcore" adventure-game player, this is what those players like. But that's a pretty small market, and for the genre to attract players from the growing casual sector, it has to be more accessible.

Conceptual non sequiturs and puzzles requiring extreme lateral thinking are two of my most egregious Twinkie Denial Conditions. I don't mind if the solution to a puzzle is unusual, and requires building MacGyver-like contraptions, as long as the result is reasonably credible. If the solution is so bizarre that the player can only find it by trial and error, the designer has failed.

Sierra Entertainment's Gabriel Knight 3

Ron Gilbert, the designer behind the Monkey Island series, objects to "backwards" puzzles -- puzzles in which you discover all the parts needed for the solution before you find the puzzle itself.

Such an arrangement encourages the player to pick up everything she sees just in case she might need it later, and I agree that that feels weird -- you're walking around carrying an odd collection of objects for no apparent reason.

He feels that the player should come upon a puzzle without the solution in hand, and so be inspired to further exploration, and I see his point. However, I don't feel as strongly about this issue as he does. I think excessive obscurity is a much worse sin.

Bad dialog. Adventure games have more dialog than any other genre, and it's usually an important part of the gameplay rather than exposition that you can button through.

Unfortunately, we're still making games where people talk far too long (and too slowly) and many conversations sound extremely stilted. Part of this can be blamed on poor localization of games originally written in a foreign language, but most of it is just incompetent writing.

For inspiration, look at TV shows that are mostly dialog, such as Law & Order. People don't jabber on for ten minutes at a time; most entire scenes last less than three. Keep it short and snappy.

Bad acting and audio production. Bad writing can very occasionally be saved by good acting, but bad acting can make even good writing sound terrible. Again, adventure games are often about people, so human interactions have to sound real.

Hire decent actors and record them acting together. Too many scenes in adventure games have clearly been recorded one line at a time, with only one actor in the voice booth. The result doesn't sound like acting, it sounds like a narrator reading lines.

The BBC, one of the last broadcasters in the world that still produces English radio plays, always records all the actors together around one microphone -- and if they're supposed to be in a kitchen, they'll be in a kitchen set, so the ambient room sound will be correct.

I realize that you can't record the contents of a dialog tree exactly the same way you can record a linear script, and we're unlikely to ever get perfectly natural-sounding conversations.

Still, when I was doing the voiceovers for Madden NFL Football, I learned the benefit writing the content that we actually needed into the middle of a longer sentence or paragraph.

We'd have the talent record the whole thing, then cut away the material we didn't need. The resulting audio sounded as if were part of a continuous flow of speech, rather than a single word or line recorded by itself.

Music. Maybe it's just the examples I've played recently, but the music in today's adventure games seems a bit tinny and repetitive compared to that in the Good Old Days. It sounds as if some corners are being cut here to save money.

The breast fixation. I have the feeling that the artists (predominantly male, alas) who created the games I have been playing fantasize about women a lot, but they don't actually look at women very much.

Culpa Innata includes a scene in which someone is giving a speech to a roomful of people. All the women in the audience, without exception, have enormous -- and perfectly identical -- breasts.

This is another Twinkie Denial Condition, and I'm disappointed to see it still being perpetuated, especially in a genre where a large proportion of the target audience is female. Grow up, guys -- and learn a little about the variation in human anatomy, while you're at it.

In 1989 -- so even farther back than my "It's Time to Bring Back Adventure Games" article -- Ron Gilbert wrote an excellent collection of rules of thumb for designers called "Why Adventure Games Suck and What to Do About It." In fact, his list is valuable for anyone working on a game with a story in it, and I strongly recommend it.

In the next few years, thanks to digital distribution, free game development tools, and the indie game movement, we'll start seeing all sorts of funky games that won't ever show up at Wal-Mart. Architecture games. Train simulations. Archaeology games. And classic, puzzle-based adventure games.

We can't all make Mario or Halo, and not all of us want to. Anybody who wants to compete directly with Mario or Halo had better have tens of millions in the bank just for marketing alone. If you develop for a niche market, you'll never get filthy rich, but you won't have to struggle against a giant corporation's PR machine, either.

Adventure games have found their niche. Drop by AdventureGamers.com, the Adventure Shop, and JustAdventure+ and take a look. You might be surprised at how many there are. Her Interactive keeps cranking out the Nancy Drew games at a steady pace, and there are now close to 20 of them. As long as there are people who want to play adventure games, there will be people who want to make them. And we'll still find ways to improve them.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like